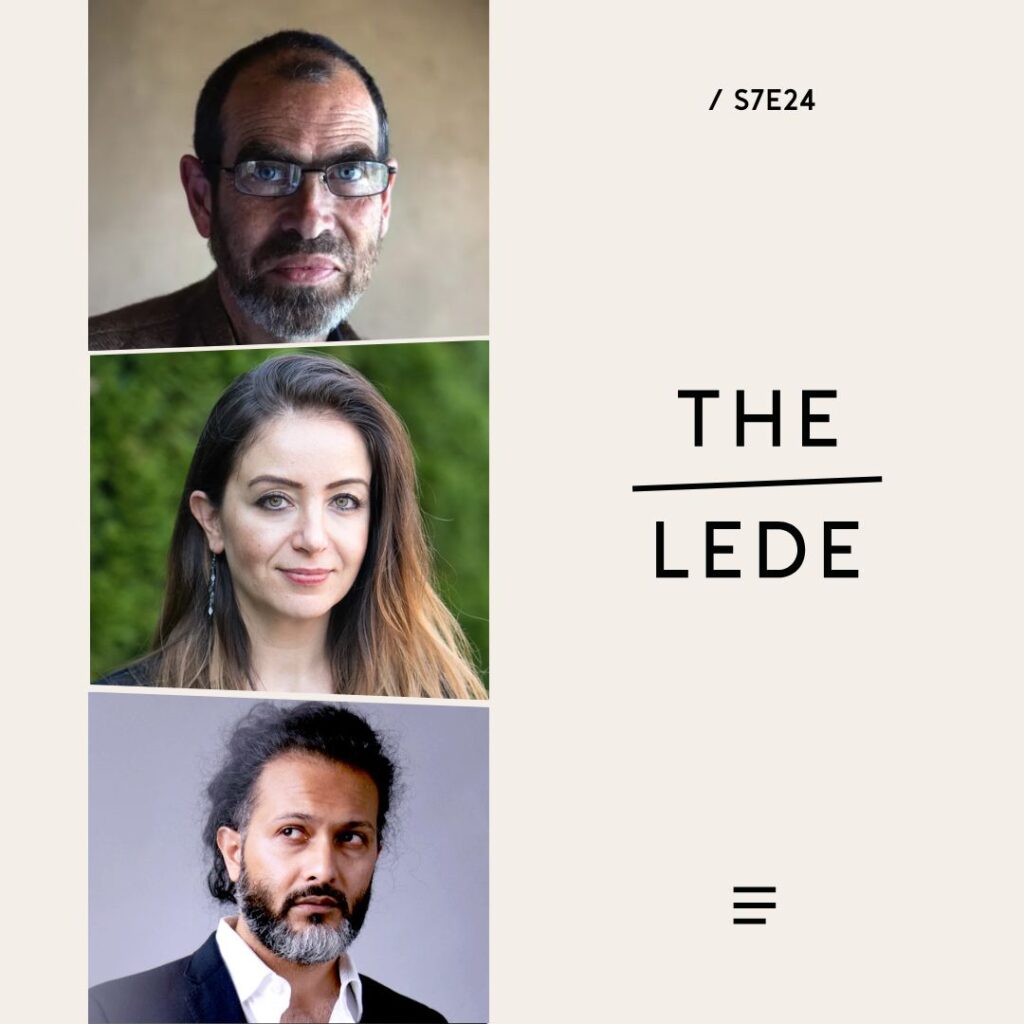

Hosted by Faisal Al Yafai

Featuring Robin Yassin-Kassab and Zaina Erhaim

Produced by Finbar Anderson

Listen to and follow The Lede

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Podbean

A lot has changed since Robin Yassin-Kassab’s last visit to Syria. The last time, he remembers, “There was a great deal of enthusiasm, a great deal of optimism. This time the optimism is wearing thin,” the co-author of “Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War” and author of the novel “The Road From Damascus” tells New Lines’ Faisal Al Yafai on The Lede, speaking from the Syrian capital.

Since the fall of former President Bashar al-Assad, things have not improved as quickly as people hoped. “The electricity situation in Damascus is a little bit better than it was, but not much. The economic situation is just as bad, if not worse. And of course there’s recently been terrible violence in Sweida, there’s been a lot of Israeli bombing, including right in the center of the city. It’s quite a febrile, tense atmosphere and people are really quite worried about what’s coming,” he says.

“I’m not sure whether the state might be collapsing, but what I’m seeing is not a new home being built.”

The intercommunal tensions driving violence in the south and elsewhere are a hangover of the Assad regime, “which used divide and rule as its main strategy, setting different sects and ethnicities and regions and tribes and families against each other, and 14 terribly violent years of civil war, which became, in one way or other, a sectarian war,” Yassin-Kassab says.

The terrible violence, foreign interference and widespread misinformation is driving division, he says. “People are angry and they are not ready to listen to different perspectives. At the moment, they’re not ready to understand that there may be more than one truth. It is a very delicate, very difficult situation and I just hope that Syria can get through it.”

Syrian journalist and New Lines contributor Zaina Erhaim remembers witnessing communities in western and eastern Aleppo turn on each other during the civil war. “I understand how this disconnection can actually lead to people dehumanizing each other and eventually not minding each other killed,” she says.

Like Yassin-Kassab, she sees intervention by neighboring Israel as a key driver of further instability. “The bombing by Israel of the Ministry of Defense, which is right in the center of Damascus, was quite a shocking moment. I think it made a lot of Syrians think that the government is spiraling out of control. It’s unable to protect its own borders. The last period of these clashes and attacks has made people feel that things aren’t as safe or as stable as they thought they might be.”

Erhaim laments the dominance of military-minded men in the political space. “Like all conflicts, sadly, those with higher impact and louder voices are the ones who are most extreme, and they have arms,” she says.

“I’m not sure whether the state might be collapsing, but what I’m seeing is not a new home being built,” Erhaim says. “What I’m seeing is not leading to stability. I’m still seeing people grouping, going back to their tribes, going back to their toxic identities.”

When Al Yafai queries her lack of optimism, Erhaim responds, “I’m not that surprised, but I’m saddened as I thought we’re the majority now as Syrians who want peace and coexistence.”