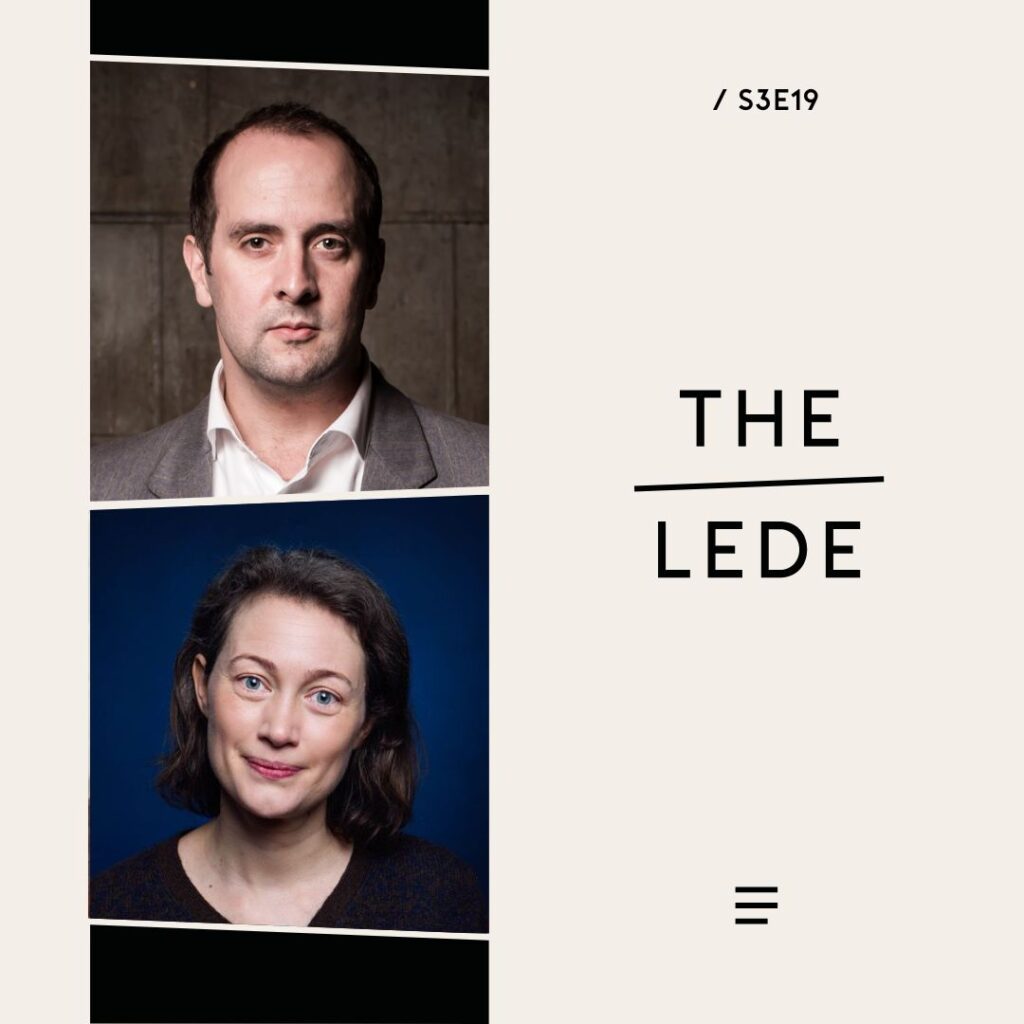

It was Christmas Eve when a longtime colleague contacted composer Tarik O’Regan to tell him that the U.K.’s new king wanted him to write a piece for his upcoming coronation. “I thought he was actually winding me up slightly,” he tells New Lines magazine’s Lydia Wilson.

O’Regan had met Charles III more than 15 years ago, at a performance at Lincoln Cathedral, and he had clearly made an impression on the then-Prince of Wales. The king’s detailed interest in his work surprised him, given the 74-year-old monarch’s reputation as a man with generally conservative artistic tastes. As a composer, O’Regan is known for incorporating a diverse range of influences and inspiration in his work, blending genres and traditions from outside the world of classical music.

“Increasingly, I don’t think of the different genres of music or different styles of music, as being separated by how they sound,” he says.

“You want to write a piece that then lives on.”

Many of his biggest influences came from childhood, he explains. Growing up with an Irish father and a North African mother, O’Regan explains that rai music was almost always playing on the radio when he would visit family in Algeria. “Those moments I remember very vividly,” he says. Rather than try to reproduce the technical conventions of rai, he wanted to try to capture the way those moments he felt when he was a child.

“I was interested in trying to write pieces of music that are not ethnographic,” he explains. “So they’re not interested in authenticity but more about focusing on the haze of memory and recollection and the inaccuracies that creep into recollections and memory.”

Rock and roll also featured. “I was born in ’78, but my mother was playing a lot of Led Zeppelin, which she’d grown up with in the late ’60s,” he says. “When you’re 5 or 6, you’re very reliant on what is played around you.”

Despite the long history of monarchs using music to shape their image and legitimize their rule, O’Regan says that he thought little about those dynamics while composing.

“One of the biggest things I was thinking about was not just how it’s going to fit into the service, but how other people might be drawn to it,” he reflects. “You want to write a piece that then lives on.”

Produced by Maggie Martin