In recent decades, one subgenre of science fiction has emerged as the de facto vision of the future: cyberpunk. Fed up with the overly utopian visions of the future cultivated by events like the moon landing and served up in popular culture like The Jetsons and Star Trek, cyberpunk sought to complicate this with a “high tech, low life” countervision rooted in a dystopian lens.

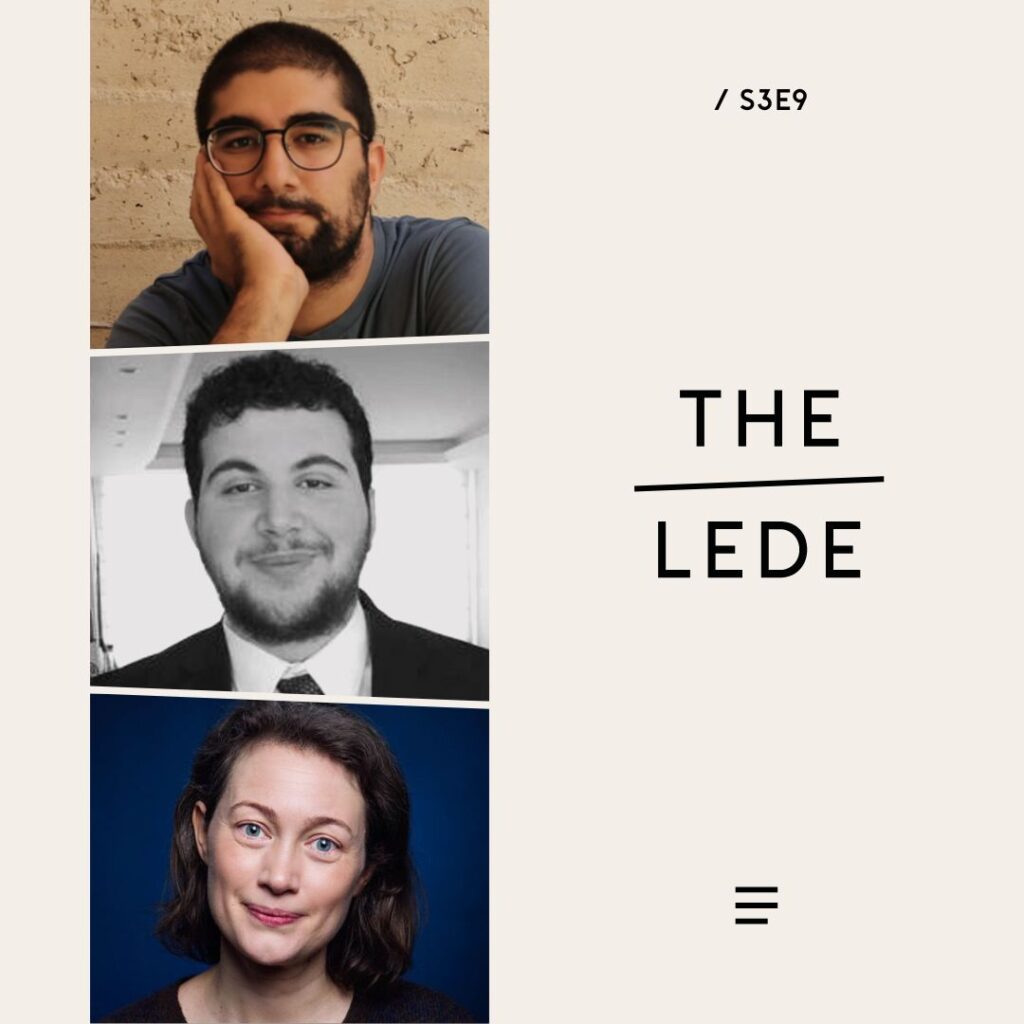

“Early cyberpunk writers like William Gibson wanted to change how we viewed the future, because they didn’t think we were heading into a good place,” science fiction writer J.D. Harlock tells New Lines magazine’s Lydia Wilson. But today, in the face of global crises like climate change, that warning has lost its edge: “We’re just oversaturated with dystopian and post-apocalyptic imagery,” says the writer and researcher Elia Ayoub. “It’s very easy today to imagine the apocalypse. And so I think there’s been this growing need to have something beyond cyberpunk.”

“It’s very easy today to imagine the apocalypse.”

Something, perhaps, like solarpunk — a literary and art movement which imagines a future in which humanity actually succeeds in solving its major challenges, like global warming and inequality. While it has retained cyberpunk’s focus on the social consequences of technology, solarpunk is optimistic, imagining a utopian future where humanity has the potential to work through its problems. If cyberpunk was the warning, solarpunk hopes to be the solution.

“If we want to imagine what we want as an alternative to the things that we oppose, we need to literally be imagining it, we need to exercise that muscle, so to speak,” says Ayoub. “What is this vision that we are fighting for? What does it look like? What does it feel like? How does it feel to live in such a society?”

“The point of solarpunk is that it’s a radical solution to radical times,” agrees Harlock. “We’re going to be forced into these radical solutions, whether we’re willing to go along with it or not, because the world can’t really continue the way it has been for the last 30 years.”

Produced by Joshua Martin and Christin El-Kholy