Imagine stepping into a dark exhibition space where a life-sized black and white film is projected onto fabric panels, transporting you to Cairo in the 1930s: Street trolleys weave around busy streets where women and men are in Eastern and Western dress. Painted crimson red, the next rooms are dedicated to the first Egyptian feminists. A 78 rpm acoustic gramophone plays a record of songs by Munira al-Mahdiyya, one of the rare women to produce a commercial recording before World War I. One floor up, parting red velvet curtains, you enter an extraordinary world of cinema and music; one that played a major role in the cultural life of the greater Middle East from the 1920s to the 1970s.

This is the long-awaited exhibit on Arab divas at the Institut du Monde Arabe (IMA) in Paris that runs from May to September. It celebrates the lives of Arab feminists who emerged in the early 20th century and female artists in film and music in Egypt during what is known as the country’s golden age of cinema from the 1940s to the end of the 1960s. At the same time, “Midnight in Cairo: The Female Stars of Egypt’s Roaring ’20s,” a book by Raphael Cormack, an academic specializing in Egyptian theatre, just launched in the U.K. and Egypt (it was released in the U.S. in March). The themes in both the exhibit and the book include female grit, feminism, glamour, stardom, empowerment, and an ebullience of artistic and intellectual creativity. These subjects are rarely included in portrayals of the Arab world today.

Yet this world most certainly did exist, and over the past 30 years there has been a steady increase in cultural productions inspired by Egypt’s golden age, not to mention more recently a number of nostalgic social media sites dedicated to photographs of the Arab world during this period.

Take the Egyptian photographer Youssef Nabil, who began his career shooting portraits in hand-colored gelatin silver prints inspired by Egyptian cinema of the 1950s and ’60s that he loved as a child. The Lebanese musician Yasmine Hamdan began to sing in Arabic after hearing a song by the Druze princess, singer, actor, and spy, Asmahan — née Amal al-Atrash — who gained stardom in Egypt in the 1930s and ’40s. When Hamdan was still part of the trip hop duo Soap Kills, she reinterpreted Asmahan’s “Ya Habibi Ta’ala” (Come my darling) in 1999, going on to adapt a number of Arab classics, in particular on her 2013 album “Ya Nass” (Hey People), reworking the structure and the melody of the songs. She has said that she felt these songs were written for her; that they were modern and eloquent, and that she became obsessed with them.

“Obsession” seems to be the recurring theme here, and one that Lebanese artist and author Lamia Ziadé uses to describe her five-year period of research before the publication in 2015 of her 576-page illustrated book “Ô nuit, Ô mes yeux,” (Oh night, Oh my eyes) which covers 70 years of history via the lives of singers Asmahan, Umm Kulthum, and Fairuz. Like Hamdan, Ziadé began with Asmahan, wanting to tell the story of the alluring star who drowned in the Nile in a car crash at age 27 under mysterious circumstances. “Little by little, I discovered the 1920s and ’30s and names I didn’t know; feminists, singers, and as I progressed in my research I became completely obsessed and wanted to discover more and share more,” Ziadé told New Lines.

Cormack, currently a visiting researcher at Columbia University, was in Cairo in 2010, doing research for his doctorate degree on Egyptian theatre and found hundreds of sources in entertainment magazines from the early 20th century that revealed a time when “incredible stuff was going on in downtown theatres and cabarets and then cinema,” Cormack said.

It was the stories of the women that jumped out at him. Cormack’s mother is the British classicist, Mary Beard, whose feminist manifesto, “Women & Power,” explores the struggles of powerful women throughout history. He found a few books in Arabic and French about them but no recent books in English — Virginia Danielson’s authoritative biography of Umm Kulthum was published in 1997, while Viola Shafik’s “Popular Egyptian Cinema: Gender, Class, and Nation” was published in 2007.

“I tried to weave together all these stories and describe what it would have been (like) to be in Cairo during the (19)20s and 30s. I wanted to tell a different story of Egypt compared to the one we’re shown in Western bookshops and a different history of Egyptian feminism,” Cormack said about his book in March at the Middle East Institute.

The years following World War I in Egypt were marked by revolt against British colonial rule, and in 1919, Egyptian women took to the streets alongside men, led by Huda Shaarawi, (raised in her upper-class family’s harem), who became one of the country’s leading feminists over the next few decades. These were heady times in Egypt — Ottoman control of the region was over, and there was a growing sense of pride among Egyptians following their independence from the British, even if they were still conspicuously present on Egyptian soil. A second Nahda, or renaissance, was in bloom. As Cormack describes in his book, the early 20th century Egyptian feminists most often mentioned are Shaarawi, Nabawiyya Musa, May Ziadeh, and Ceza Nabarawi, the majority of whom were from middle- and upper-class backgrounds. But Cormack tells us, “outside of this world, another history of Egyptian feminism was being written on the stages of Cairo’s nightclubs, theatres and cabarets.”

These women had grown up very often in poverty with little education and were not considered respectable by a conservative society. Yet the singer and actor al-Mahdiyya ran her own theatrical troupe for several years before the Egyptian Feminist Union was founded in 1923. Those lucky enough to forge a place for themselves in a traditional society were part of this emerging Egyptian culture and “achieved significant personal and financial independence.”

Rose al-Youssef, who appears to have arrived in Alexandria as a young girl, penniless and without a family, became successful in two worlds — first as a vaudeville star, and then as an editor when she founded a political magazine in 1925, with a widely followed page that covered entertainment gossip.

It’s a past that many people in the West don’t know about, and “even Arabs have forgotten,” said Ziadé, adding that she wanted to conjure this magical world, preserving it on the pages of her book, in contrast to the unrelentingly difficult times the region is going through today.

The curators of the exhibition at IMA, Hanna Boghanim and Elodie Bouffard, describe these divas in the exhibit catalogue as not only brilliant performers who overcame the constraints of patriarchal societies but also women “who are still recognized today as the basis of a common Arab culture.”

In the latter part of “Midnight in Cairo,” we learn the details about the making of the 1927 “Laila,” the first Egyptian film produced, no less, by a woman, and its starring actor, Aziza Amir, who went on to make several more. Cormack also describes the rise of film star Bahiga Hafez in the 1930s, who was unusual in that she was from a wealthy family. When interviewed for the French-language feminist magazine established by Shaarawi, L’Égyptienne, her answer to the question of why she became an actor, was her “desire to smash these heavy chains which prevent me and every other educated Egyptian woman from showing the world they are no less capable or productive than women in the West. I am a supporter of women’s freedom … to do honest work instead of spending … time imprisoned in the house.”

The golden age of the Egyptian film industry was intimately linked to music; singers often became actors, and musicals were a large part of the production. Aspiring stars from the Arab world traveled to cosmopolitan Cairo where they adopted the local dialect and tried their luck. Assia Dagher emigrated from Lebanon in 1923 and went on to act in 20 films and produced nearly 50. Dagher’s 1945 film “El-Qalb luh Wahed” (The Heart Has Its Reasons) launched the singer Sabah’s career. Dagher’s niece, Mary Queeny, an actor and later a producer, was one of the first women to appear on screen without a veil.

Asmahan, who inspired so many contemporary artists doubtless because of her talent, beauty, and nonconformist private life, sang and acted in films in the 1930s and ’40s, before her untimely death in 1944. It has been said that Asmahan was the only singer who posed a serious threat to Umm Kulthum’s unparalleled status as “the voice of Egypt.” At the time of her death, Asmahan was starring in the film “Gharam wa intiqam” (Love and Revenge), which was nearly finished; the last scenes had to be shot without her. Several of the songs in the film, including the mythical “Layali el Ouns fi Vienna,” (Nights of Love in Vienna) were composed by her brother Farid al-Atrash, also a singer and actor. In 2019, her great granddaughter, the Swiss Lebanese Yasmina Joumblatt, working with French Lebanese composer Gabriel Yared, performed a tribute to Asmahan at the Beiteddine Festival in Lebanon, where she sang, among others, nine original songs by the star.

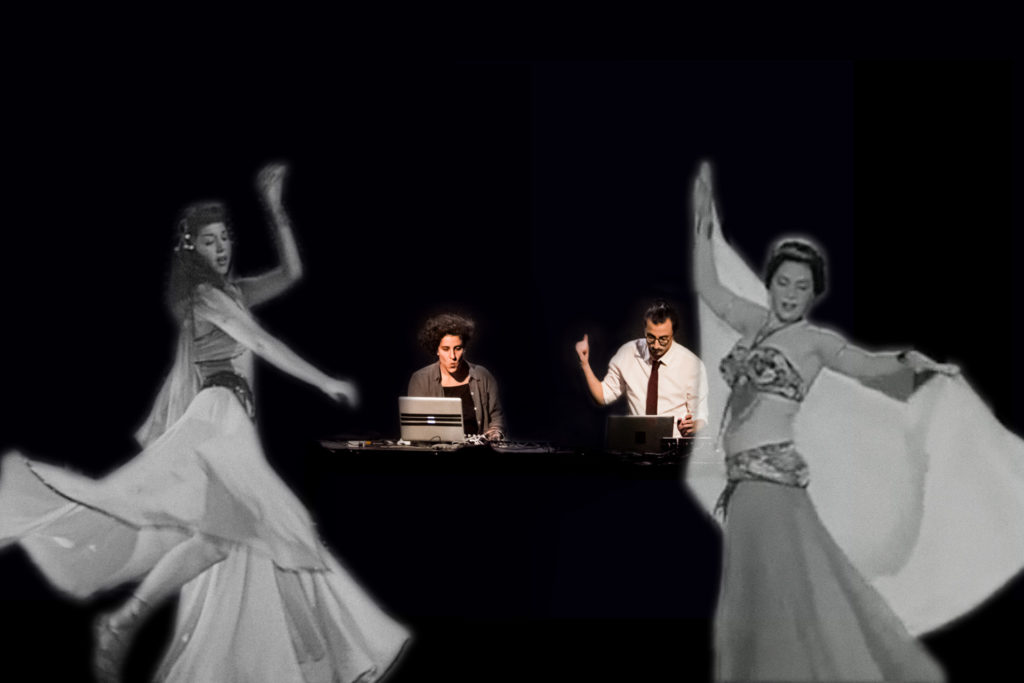

“Love and Revenge” is the name the composer Wael Koudaih (stage name Rayess Bek) and visual artist Randa Mirza (also known as La Mirza) adopted from Asmahan’s last film for their acclaimed audio-video performance that launched in 2014, in which they sample music and extracts from Egyptian movies from the 1940s and ’50s, giving them a modern spin. Mirza, who hadn’t paid much attention to these classics when she was growing up, dug into cinema archives on YouTube to find over 100 images she could pair with Koudaih’s music sampling. She told New Lines that she had discovered “a sensuality that I hadn’t known about. Women were strong and frivolous and manipulative, all the while playing the role that was expected of them.”

Mirza wondered about this idealized image of women portrayed as beautiful seducers: “Is this freedom and feminism?” Still, “even if I questioned this heteronormative model in films made (mostly) by men, I was seduced.”

In the end, “Love and Revenge” became a “joyful and intelligent project that makes you feel and think,” she says. The duo began performing in 2014 in Egypt, eventually adding musicians Mehdi Haddab and Julien Perraudeau to the production as they started touring Europe and the Middle East. “I never saw a project take off like this one — from a small village in Norway to the trendiest places in Paris, everywhere, people got something out of it. Europeans discovered a world they never knew existed, and the Arabs clung to it because it reminded them of their parents and their culture,” said Mirza.

The incredible sensuality of these stars, such as dancers and actors Samia Gamal, Tahiyya Carioca, (who married 14 times and was jailed for three months for communist activities) and later, Nadia Gamal, have all provided inspiration for today’s artists. The Lebanese visual artist, actor, and writer Nasri Sayegh began his Radio Karantina Instagram account during the first coronavirus lockdown, building on his habit of trawling through old films late at night. He has since created 1,000 video collages in which he brilliantly pairs a dance sequence, from a Nadia Gamal film for example, with Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven,” or Samia Gamal and David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance.”

But Sayegh also joins West with East with 1940s and ’50s Hollywood actor and dancer Cyd Charisse with the Upper Egypt folk group, Musicians of the Nile. “It’s an obsession, and the pleasure of sharing a time when bodies expressed themselves differently, and there was more space for discussion,” he told New Lines. “I take refuge in this beauty of our region, this continent that is our Arab world, and a well of imagery when the body was uninhibited. … I’m taking refuge from the dead end we’re in. When I dig for these images it’s a random political act, it’s a way of saying we are here.”

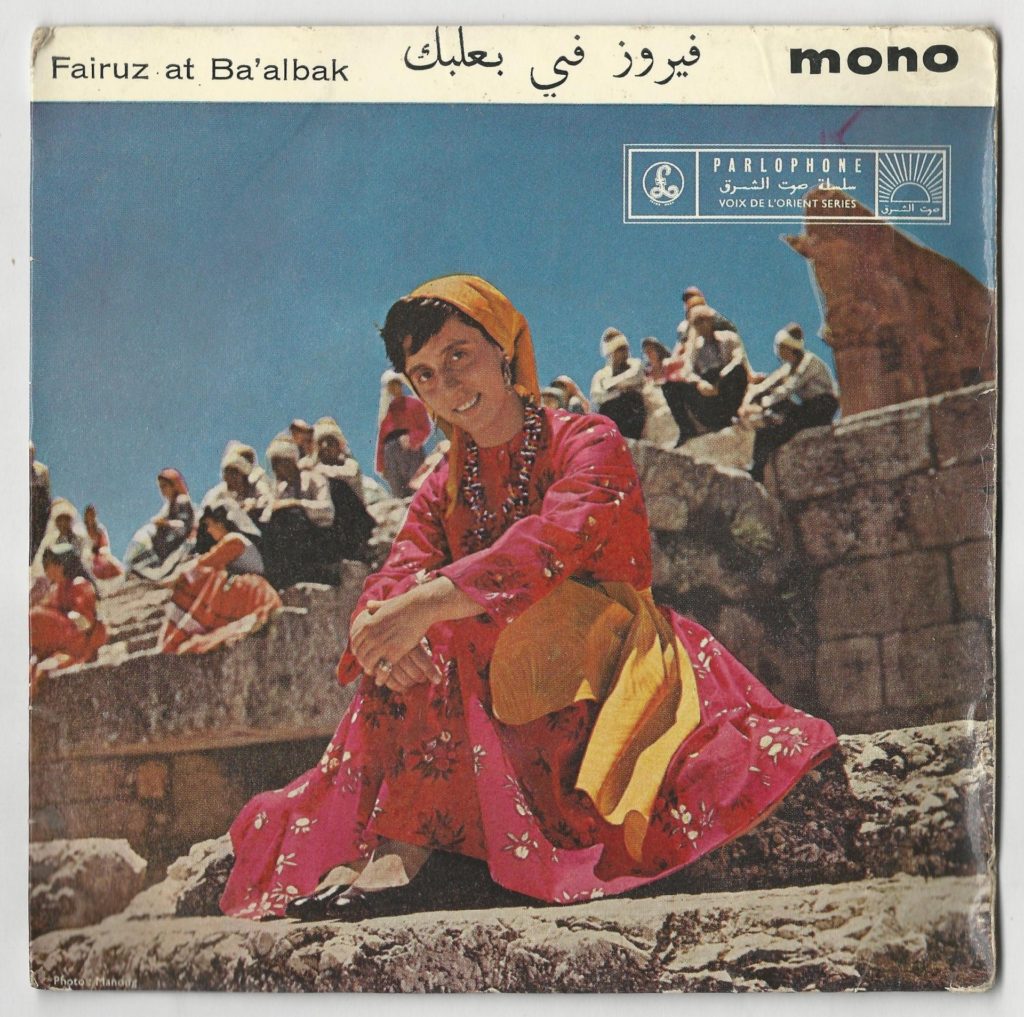

The two divas whose voices seem to go beyond sexuality, attaining a quasi-religious iconic status are the great Umm Kulthum and later, the “soul” of Lebanon’s Fairuz.

A character in Lebanese author Hoda Barakat’s novel, “The Disciples of Passion,” translated by Marilyn Booth, describes Umm Kulthum’s voice as “saltiness and sweetness — an asexual voice, but a bisexual one, too. The lyrics to her songs are in a masculine voice but one that encompasses the feminine. … women hear her as a man, and men hear her as a woman.”

The number of documentaries, films, and art projects that Umm Kulthum and her voice have inspired are enough to make one’s head spin; not to mention the merchandise such as dishtowels, mugs, or handbags stamped with her image. But both Umm Kulthum and Fairuz were also politically engaged women — the former fervently nationalistic, and although often accused of being a mouthpiece for Gamal Abdel Nasser, she embodied pan-Arabism, while the latter raised awareness about the Palestinian cause and backed left-wing Arab groups while attempting to unite all Lebanese during the civil war.

The exhibition at IMA shines the spotlight on a number of women who are not as well remembered as Umm Kulthum, such as the beloved star of Egyptian musicals, Laila Mourad, who was Jewish, or Warda, who was born in Paris of Algerian parents and began singing in her parents’ cabaret, the Tam Tam, in the Latin Quarter. France was in the throes of the Algerian war for independence, and Warda and her family, although of French nationality, were thrown out of the country. Warda became a star in 1960s Cairo and shuttled back and forth between Egypt, Algeria, and eventually to France, for concerts.

In Ziadé’s “Ô nuit, Ô mes yeux,” from the 1967 Six-Day War to the 1980s, when she ends her book, the color drawings become more muted, and faces are often left without features. She made this choice, she said, to indicate a world that has disappeared; a place where cosmopolitanism was a reality, and where secular ideology was plausible.

“This need not be the story of a lost golden age,” writes Cormack in his book, underlining that life in those days was definitely not easy for women who “faced disparagement, prejudice, even violence, and they were sexualized by men who wanted to either possess or police their bodies. For most people, especially women, the golden age of Cairo was no utopia.” Nevertheless, he continues, following the 1919 revolution, “Egypt offered something intangible but vital: possibility. … There was a space for women to make their voices heard. Some triumphed, some failed. … but all of them were navigating a new world. That sense of possibility is what makes this period so compelling.”

This sense of possibility continued until the late 1960s, when politics in the region began to be driven by religious sects and ethnicity, and most countries suffered terrible losses from wars, either self-inflicted or afflicted by others. But it is also conceivable that this “golden age,” so evident in the joyful and powerful performances of these Arab divas, might also offer hope, in that narratives of the past can provide resources for imagining the future. In an interview about her book with Lebanese French-language daily L’Orient-Le Jour in 2015, Ziadé said, “It was a way of telling myself that if it existed before, perhaps it can exist again.”