A lasting evolution of photography is at work in Syria, where photojournalists, rebel groups, and local photographers are producing visual material in ever-increasing volume. But after a decade of disillusionment with the power of the image, it might be time for artists to give these documents another meaning.

Since 2011, the war in Syria has often been described as “the most documented conflict” in history, as ex-judge Catherine Marchi-Uhel said when she was appointed to head the United Nations International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism on Syria Crimes. Photographs and videos coming from the Syrian war zone might one day be used as evidence for prosecuting war crimes, but their purpose cannot be restricted to the judiciary. In the 10 years since the conflict began, such a vast number of images has been produced that one wonders: Why did this specific conflict yield millions of images, and what happens to them once they have been disseminated in the media?

The profusion of images coming from Syria since 2011-2012 leads to a strange impression, as if the war was broadcast live. This was made possible by the evolution of technology, but it also influenced the way reporters work, and eventually, the way we look at their images. Swiss photographer Matthias Bruggmann reported from Syria from the beginning of the war and saw how photography was transformed during the conflict and relative to what went before: “From my viewpoint as a photojournalist, this war embodies a crisis in photography and a deep political crisis in Western countries. I see a difference between Syria in 2011 and Iraq in 2003-2004, where journalists were embedded with the U.S. Army,” he says.

In Iraq, one coherent narrative of the war consequently emerged. “In Syria, from 2012, you had regime media, and you had opposition activists with smartphones and access to distribution channels,” Bruggmann adds. “Later on, every opposition group and every rebel battalion set up its own unit to produce photographs and videos. And after the opposition took over most of Idlib and eastern Aleppo, it became much easier to enter the country, so inexperienced foreign reporters started flocking in. So, in a way, everyone became a propagandist!”

While more international reporters came to Syria, young citizen journalists inside the country took up photography as a means to earn money. French Syrian photographer Ammar Abd Rabbo is one of the experienced professionals who offered the young ones training, which came with many challenges in a country where press photography had always been suspect: “Before 2011, real press photography in Syria barely existed. Even if international press agencies had correspondents, they were always linked to the regime one way or another.” Following implicit rules implemented by the regime meant taking photographs that stick to the official narrative, as Rabbo points out. After 2012, he noticed would-be photographers lacked the basic training for press photography. “I had to teach them what is allowed and not allowed when taking a picture. I noticed some of them used to set up a scene with people acting as extras,” he says. But after receiving good training, many of these photographers would go on to work at international press agencies, such as Reuters and the AP.

In 2013, after a series of killings and abductions, the situation for photojournalists changed radically. “After the deaths of Marie Colvin and other reporters, foreign media stopped sending photographers to Syria,” says Bruggmann. “Then, after the abductions of foreign journalists started, they pretty much stopped sending international journalists … because they figured the public’s interest wasn’t worth the risks. And the regime won the war of narratives.”

With the rise of the Islamic State group, or ISIS, press photography in Syria became a local activity, if nothing but an attempt to counter the propaganda incited by the terrorists. According to Rabbo, the pivot point that deeply influenced the evolution of war photography and video came when ISIS flooded the internet with its own visual propaganda: “The images they made of executions and torture were very dramatic, they were used to shock the world and it worked. Syrians were probably a bit naive at first because they believed in the power of photography to change the course of the war positively.” But the images of violence that ISIS produced to create a counternarrative did not bring any major change to the conflict. Even after ISIS had been expelled from its strongholds, the war continued and the regime with its Russian allies regained control of the narrative.

Bruggmann confesses to being a little disillusioned about his activity as photojournalist: “I sometimes wonder what is my legitimacy to report on Syria. I mean, I’m not Syrian, it’s not my family being bombed, and I don’t take the same risks as Syrians on the ground.” It’s a feeling shared by Rabbo as he reflects on the purpose of publishing photographs today. “Technology was a blessing and a curse for Syrians. It’s true that it allowed us to let the world know about the war, but on the other hand nothing really changed since 2011. Even the Caesar file didn’t have the impact everyone expected,” he said. The Caesar file is a collection of thousands of photos that document torture carried out by the Assad regime, which was smuggled out of Syria.

Even though they often feel discouraged, photographers like Bruggmann and Rabbo can still find other ways to show their work. Exhibiting it is one way to reach a larger audience, and that is what Bruggmann has done in the past four years. His photographs are regularly shown in galleries in France and Switzerland, and he won the Prix Elysée award (a prestigious prize for photographers awarded by the Swiss museum musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne) for his work on Syria in 2018. Rabbo put up exhibitions in France in galleries and in the streets as a way to let people see these pictures, even if they are no longer published in the media. Numerous reporters who have worked on Syria have progressively shifted their activity towards documentary photography or even artistic photography, as a means to keep a bond with a conflict now seen from afar. As to the thousands of images of the war lost in the margins of the internet, they sometimes catch the eye of artists who decide to give them a second life.

But can war become a material for art, especially one as long and vicious as Syria’s? Perhaps the better question is one posed by art historian Paul Ardenne, who puts it like this: “How can artists extract from a deadly conflict shapes that will avoid the spectacular, the cliche, the morbid enticement?” He suggests it is the position from which artists look at the war that makes them legitimate or not to use it as material. “As the saying goes, war is a much too serious affair to be left to the military. Let’s hope artists can evaluate war at its best value if they are passionate about history and its context,” he said.

Khaled Barakeh is one of the artists who is repurposing Syria’s war images for art. The Syrian-born artist spent days and nights scouring Facebook posts for war-related images, with a focus on families torn apart by the violence. For his series, “The Untitled Images,” he selects photos of bombings then peels off the top layer of the print to do away with the victims’ faces and bodies. “I scratch away the faces of the victims and leave the faces of those still alive in a positive act of censorship, and as a metaphor for the collective disappearance of the Syrian people,” he explained in a conference in Paris in 2019. It is “the result of a tension between the necessity to show the consequences of the war and the respect for the victims.” When he exhibited the series in Germany, Barakeh chose to hang the frames very low, close to the ground of the gallery, which forced the visitors to bend down, almost as an act of respect toward the victims.

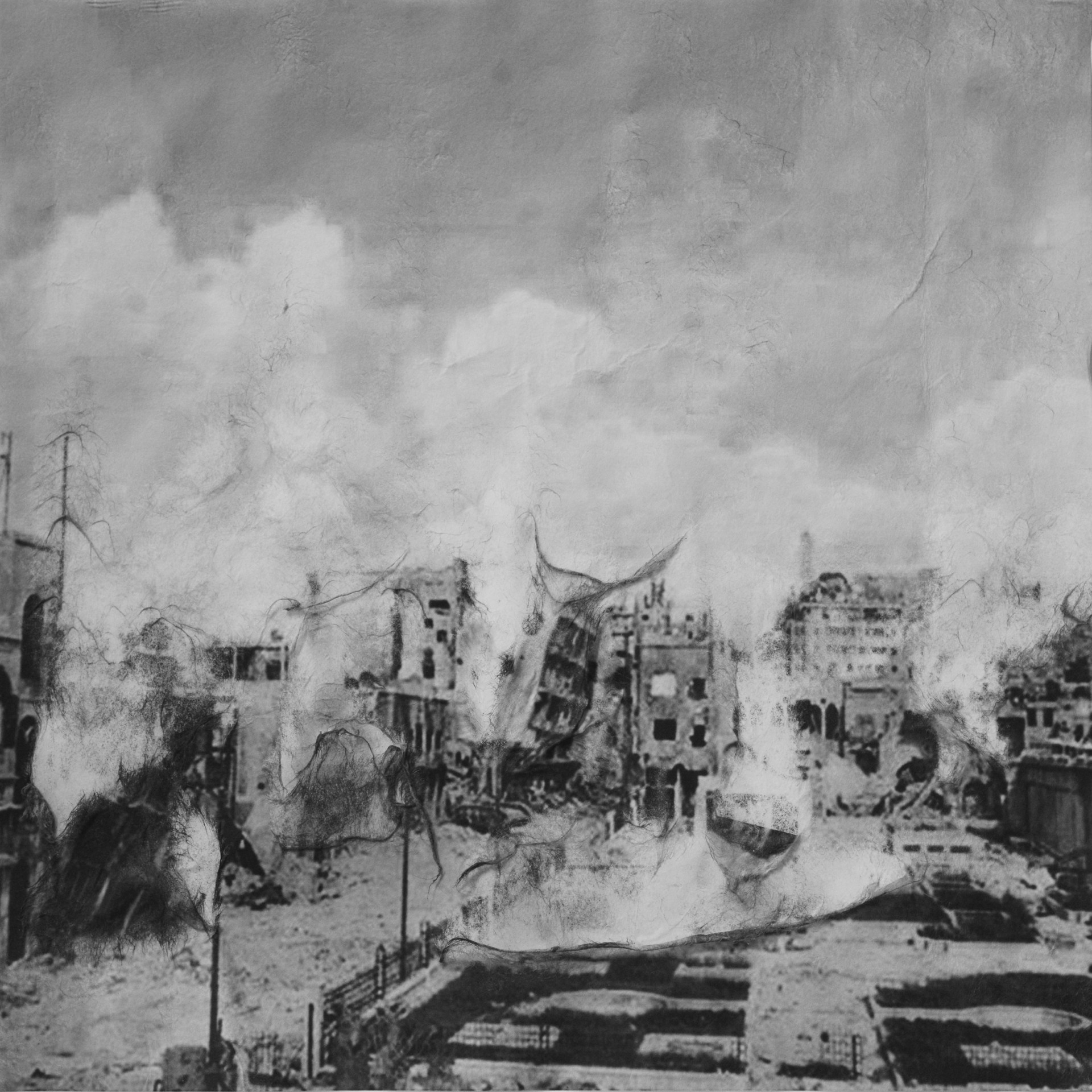

Working on the texture of photographic prints is indeed a process that appeals to many artists, such as Lisa Sartorio. The French artist selected images of the war in Syria through the archives of news websites or through posts on social media. She says she looks for “imperfect images that contain a potential for transformation,” such as derelict buildings. She is persuaded such images expose the duration of war. “I’m interested in the moment when architecture becomes a ruin just after a bombing. Ruins usually take time to materialize but in a war it happens in a few seconds,” she said.

Sartorio prints the images on a specific paper made of Japanese mulberry fiber, giving it a matte finish. She dips the print in water, then works on the texture with small moves using her fingers. As the surface of the print folds and wrinkles under her touch, the picture changes and she feels as if she’s injecting “humanity into these pictures, although there are no humans in them. It’s a way to find the right distance with this war,” she adds. The series called “Ici ou ailleurs,” — Here or Elsewhere — also contains pictures of other conflicts since 1970, the birth year of the artist. It is her way to include the Syrian war in a long string of conflicts; to give it a place in history as seen from a human scale.

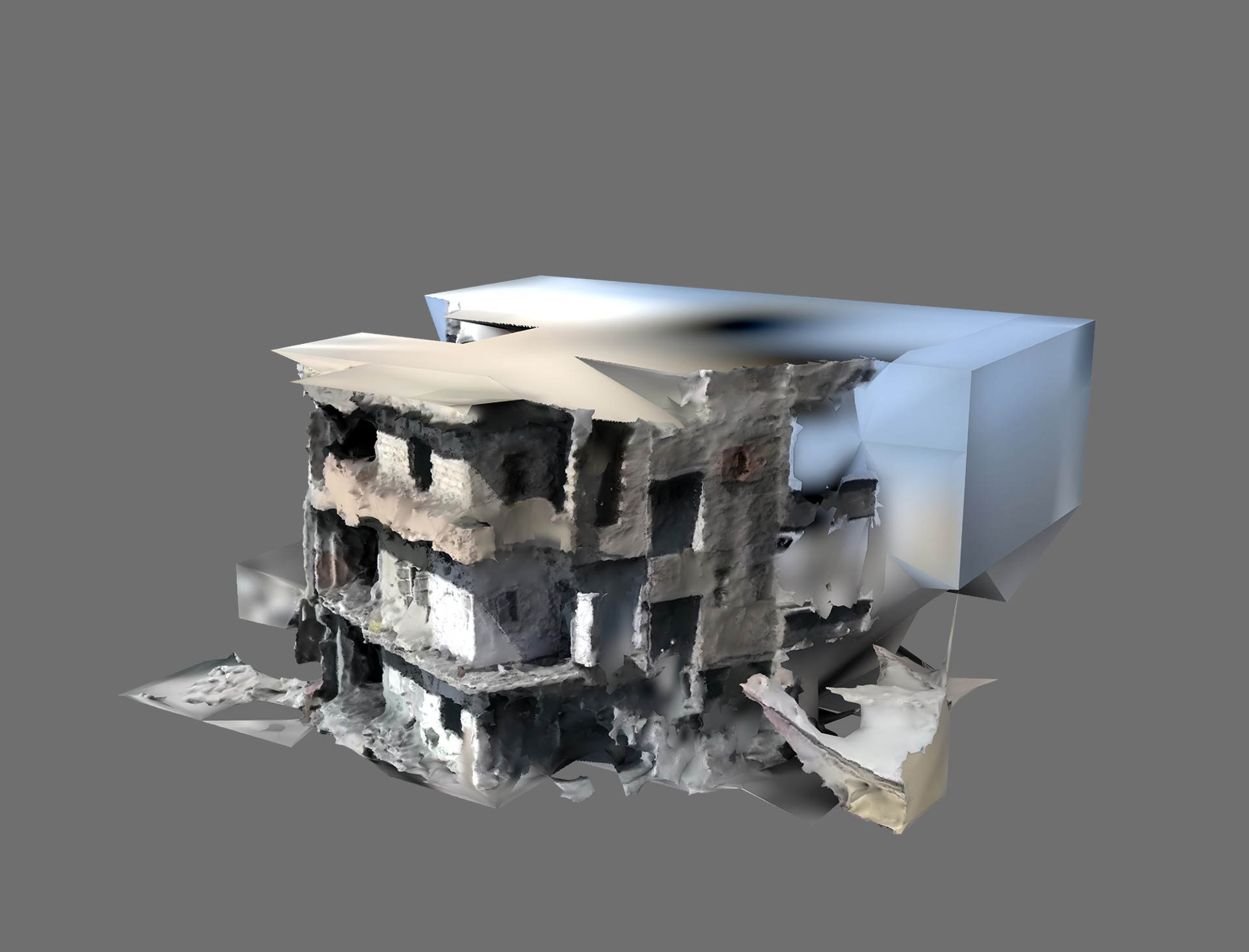

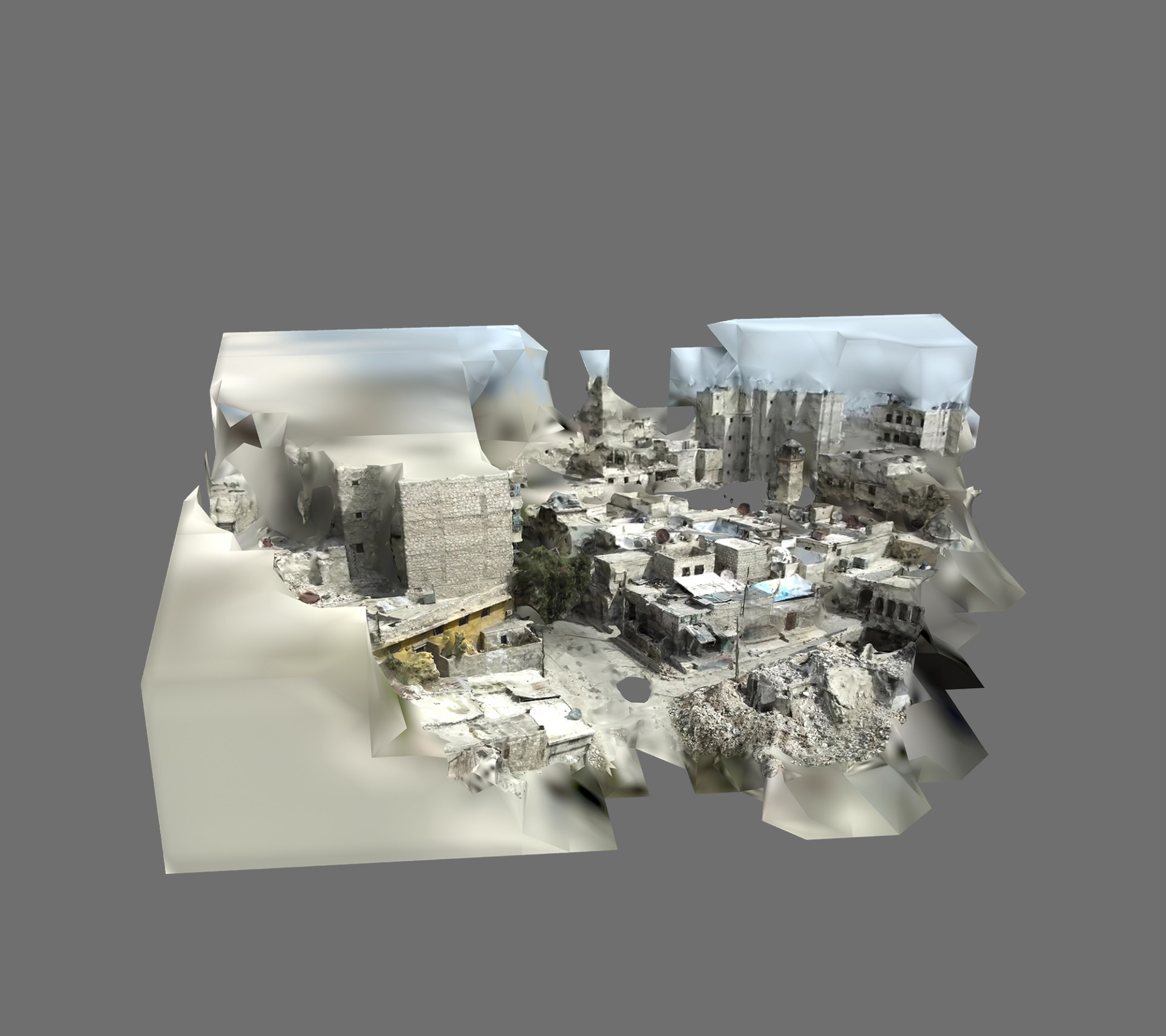

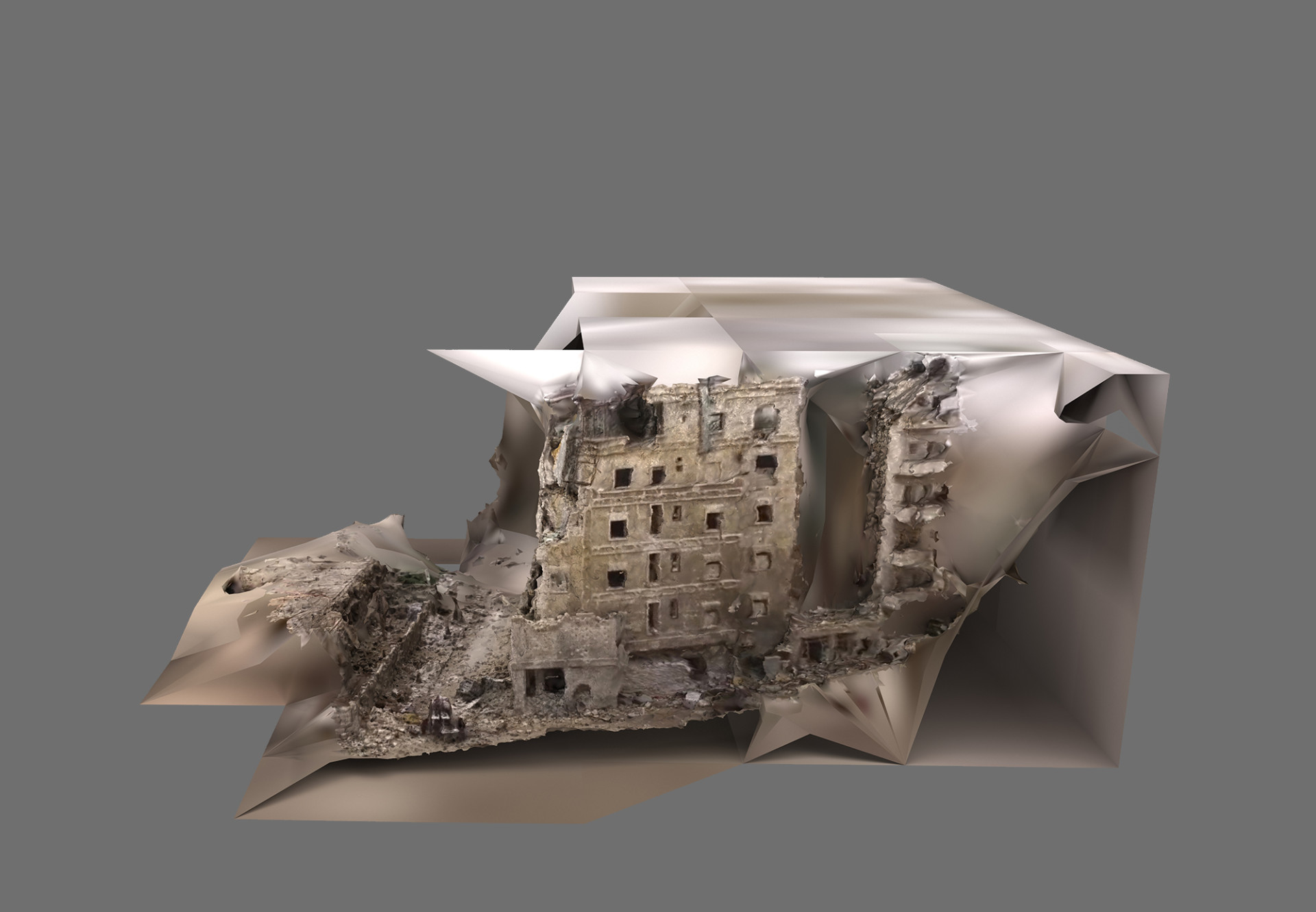

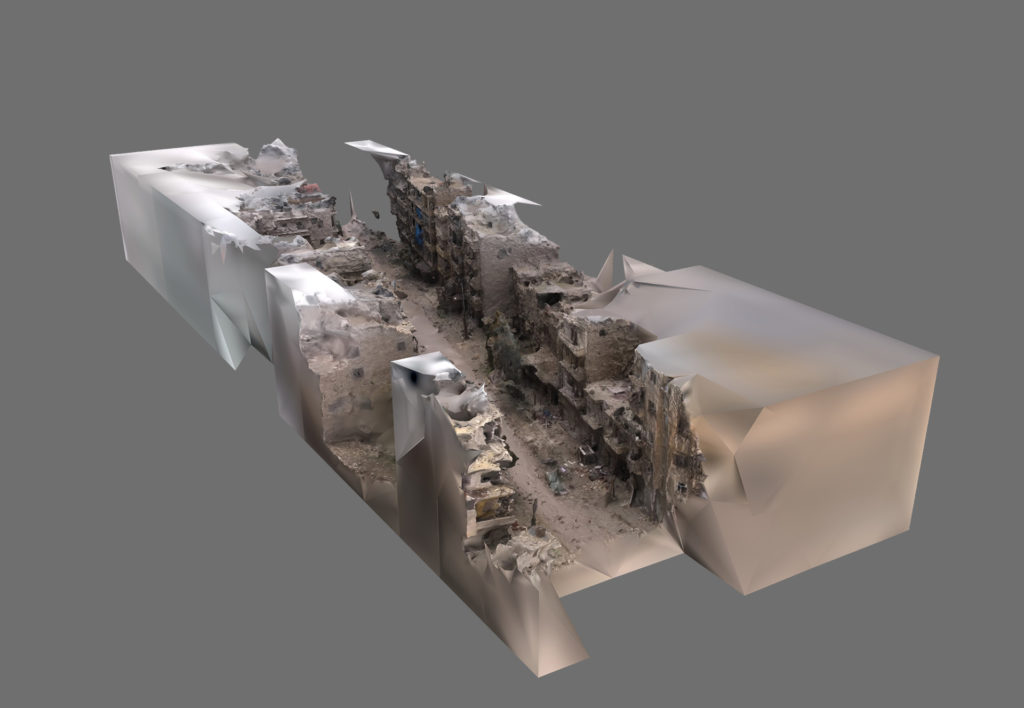

While the war in Syria unfolded, the evolution of technology enabled journalists and citizen reporters to document daily events. For French artist Thibault Brunet, it was an unexpected new algorithm that brought him into the fold of documenting the Syria conflict. In October 2018, Brunet noticed a change in his RSS and Youtube feeds while he was in the United States. “I don’t know how, but the feeds started showing videos and pictures of the Middle East and Syria every day. The topic imposed itself, and I started working on images of the Syrian war,” he said. He used software from video game design to do photogrammetry, which enables the creation of 3D objects using photographs. Brunet feeds into the software hundreds of pictures of a building or area, then the 3D reconstruction starts. He prints the 3D rendering on photographic paper, and the viewer wonders whether the image is real photography or an artist’s rendition. “The question is: What do we see of the war in Syria? And how do we avoid making it attractive?” he said.

The series is called “Boite noire” (Black box), as if the artworks were memories stored in an old box. Despite the multiple techniques involved in the process (software, 3D reconstruction, printing on paper), these artworks convey a sense of familiarity and closeness because the viewer recognizes the blue and beige shades of Syrian urban ruins that have become ubiquitous in media coverage. In an unexpected twist, last year Brunet had a few of those prints used as cartoons for tapestries woven in Paris. From digital pixels to 3D objects to photographic prints to rugs hung on the walls of a Parisian gallery, images of the destruction in Syria have been on quite a journey.

Although the aftermath of the war continues, artworks that repurpose photographs of the war may contribute to a renewed narrative. Art makes the viewer reflect on time and all the opportunities lost. Eventually, perhaps, the art helps us make sense of the tragedy.