A Polish Village Is Tested

The cracks have begun to show at the busiest border crossing for Ukrainian refugees

Medyka is the single busiest border crossing between Poland and Ukraine. Thousands arrive every day, exhausted, fleeing a war that has killed scores of civilians and leveled cities.

Volunteers eagerly greet refugees, ready to offer them hot drinks and food. Buses turn up intermittently, ready to take the refugees to a shelter — though there are no signposts to indicate where they are headed.

The crossing is rudimentary and lacks a simple but much-needed information stand. If refugees want to find out what to do next, they are left to figure it out on their own. More than two weeks after Putin started his war, there is still no sign of the Red Cross or the United Nations refugee agency.

The haphazard but generous relief response appears to be the result of a relatively hands-off approach by Poland’s authorities, who in recent years have had much more experience in turning away refugees than welcoming them. The burden of organizing the logistics of support for refugees has instead fallen on local municipalities — sleepy eastern Polish towns that have suddenly found themselves near the epicenter of what threatens to be the worst European refugee crisis since World War II — as well as NGOs and thousands of independent volunteers.

According to the latest numbers from the U.N. refugee agency, more than 2.5 million refugees have fled Ukraine since Russia’s invasion, with more than half crossing into Poland. Well over 100,000 refugees flee the country every day, and that number is likely only to grow — especially if the long-awaited humanitarian corridors from major Ukrainian cities on the front line are finally secured — threatening to overwhelm the already strained humanitarian response in Poland.

This is not to say that Poland’s decentralized response has been a failure — far from it. Tens of thousands of Poles have opened their homes to strangers, train companies have waived ticket fees for Ukrainians, and innumerable volunteers are coming to the border daily to help in any way they can.

At smaller border crossings like Korczowa — 20 miles north of Medyka — the spirit of volunteerism and municipal muscle combined with a relatively light flow of refugees has meant that nearly every arriving refugee can find a heated school gymnasium and sleep on a warm cot within an hour of crossing the border.

At Medyka, meanwhile, with thousands crossing every day, aid infrastructure is stretched to its limits.

“You can call it whatever you want to call it. It’s unsafe. It’s terrible,” says Laura Bukavina, a Ukrainian-American surgeon from the United States who has been stationed at a medical tent at the Medyka crossing. “It’s dirty. There are kids. There are 1-week-olds who are crossing and who have no shelter.”

Bukavina, who arrived in Poland with her husband and another volunteer doctor from Philadelphia, said that other border crossings put Medyka to shame. “They have great big shelters. They have lawyers walking around helping with paperwork. They have signs everywhere. Here you can’t even get a blanket.”

According to Bukavina, the biggest problems in Medyka’s volunteer-based relief system occur at night, as refugee flows inevitably fail to conform to the daily routines of the people who have come to help. She recalled one night when the majority of volunteers on location had gone home and there were no buses taking people to shelters. Refugees who had arrived then, including infants and the elderly, were forced to wait for hours in freezing temperatures. The volunteers who were there scrambled to find tents to shelter the most vulnerable, but many were left outside in the cold.

A refugee’s needs do not end when boarding the bus in Medyka. While some are transported to well-managed and relatively small shelters — primarily in school gymnasiums — most go to a shuttered Tesco shopping center located on the outskirts of the nearby town of Przemyśl.

According to volunteers at the shelter, roughly 15,000 people pass through the Tesco center on a given day, though without anyone recording the number of arrivals and departures, no one can say for sure.

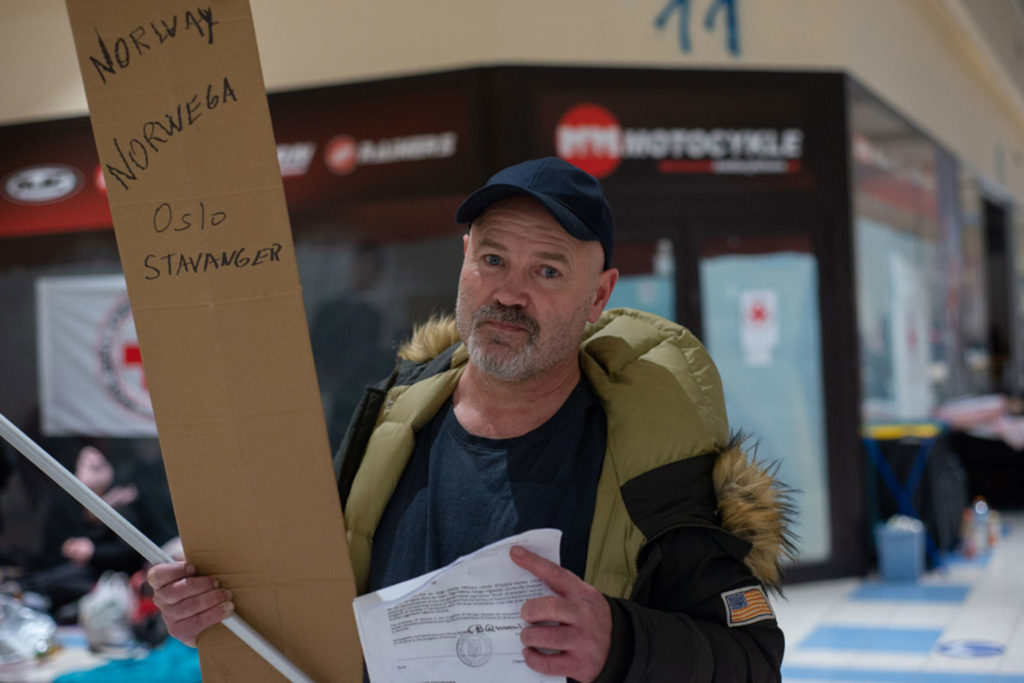

It is among the largest shelters for Ukrainian refugees in the country. Despite its size, the building has only two working sinks — one of which is constantly used to fill a never-ending train of pots and doggy dishes. Families sleep wrapped in reflective thermal blankets on donated yoga mats, while a Norwegian social worker wielding a pole with the flags of both Ukraine and Norway seeks passengers for a bus to Oslo — but only if they have a biometric passport. Unfortunately, he speaks neither Ukrainian nor Russian.

International organizations are almost as scarce here as they are at Medyka, with the exception of Caritas, which has a small tent stationed outside with people doling out much-needed advice, blankets, coffee and tea. The Polish authorities, too, are notably absent except for some volunteer firefighters and police officers.

As with the Medyka border crossing, confusion plagues the Tesco shelter. Buses, as well as individuals looking to help, show up without any discernible schedule with the aim of taking refugees throughout Poland, to other EU countries and even further abroad. According to a crudely drawn cardboard map taped to one (but not the other) set of main doors at the shelter, the building is mapped out by destination. For instance, if a refugee wants to go to Berlin, there is a designated room where they should gather. But in reality, most find out that a bus headed for their destination is ready to board people only because a volunteer has shouted out the information loud enough.

For many, the choice of where to go is a harrowing one, especially when they have no relatives or friends at their destination or have a precarious legal status.

“For now, our plan is to go to Germany. But to be honest, we decided it 10 minutes ago,” Anastasia, a 29-year-old refugee from Kyiv, told me, as her boyfriend Ahmad squeezed her arm. Their friend Anna, who joined the couple at a train station in the Ukrainian port city of Odesa, was a few steps away, having her portrait taken by another journalist at the shelter.

Anastasia, who asked that her last name be withheld, said that since their arrival at the Tesco center, the three of them had debated where to go, and she and Ahmad, an Iranian citizen and her partner of two years, discussed where they could go. “We don’t want to break any laws,” she said. Despite speaking with countless volunteers, Anastasia said she could not find a satisfactory answer. The morning after the trio arrived, they decided to board a bus headed for Prague, to leave “as soon as possible” from that “depressive and desperate place.”

At the Tesco, several layers of clothing and blankets are barely enough to keep warm / Tamuna Chkareuli

Piles of donated clothing lie in a heap at the Medyka border crossing. If it rains, they will be ruined / Tamuna Chkareuli

In one of the tents at the Medyka border crossing, children shelter from the biting cold / Tamuna Chkareuli

Sixteen-month-old Leila sleeps soundly for the first time since Kharkiv was bombed / Tamuna Chkareuli

Essay by Peter Liakhov, photos taken by Tamuna Chkareuli