Sometime around the second week in November, there’s a shift in the WhatsApp groups I frequent for foreigners living in Tunisia. After months of trading intel on where one can find whole milk, flour or rice in a country beset by constant staple food shortages, a different kind of message starts appearing: “Anyone know if, by some miracle, there are pecans to be had anywhere in Tunis?”

“I think there’s one vendor at the central market who has some in the back if you ask for them. He’s on the southeast corner, near the guy with the pickles. No guarantee of freshness,” comes the reply.

“What about fresh or frozen cranberries?” another person asks. The hunt for Thanksgiving has begun.

I can already tell you, there are no cranberries in Tunisia. I know this because this time last year, I went on what I can only describe as a hero’s journey in search of the astringent little jewels, with their tannic, mouth-puckering power to transform even the richest of dishes into something at once bright and festive. I drove across the city, thrice, made a shady backroom deal with a Maltese pork butcher, and still ended up with what turned out to be a kilo of frozen red currants for which I paid $20. I doctored them with a bit of pomegranate juice, some quince and orange peel into a delicious sauce that fooled the foreigners at my Thanksgiving table. But I knew the truth. I wondered if this is what my Tunisian friends in New York feel when they have to use the kind of harissa labeled “Spicy Moroccan Spread” for their couscous.

I’ve been an American abroad for nearly a quarter of my life, and, for the vast majority of that time, I’ve fled from anything that gave off even a whiff of America. It’s not that I’m ashamed, per se, but I left the States to see what the rest of the world had to offer, and found instead that the rest of the world was very interested in whatever America was selling.

The first time I traveled abroad alone, the summer I turned 20, was to spend the month of August on an ecological research vessel on Lake Baikal, in Siberia. It was wild and strange and beautiful being on the lake, with all its moods and tempers, a million miles away from anything familiar. One afternoon we docked on Olkhon Island, which lies less than 4 miles from the shore, but which had not had continuous electricity until just the week before we arrived. Baikal is so deep that to lay an underwater cable required special submersibles that could descend the 8,000 feet to the lake bed; one of our scientists built the little submarine that did just that. We were greeted on the island by a team of researchers who proffered a rare delicacy — ice-cold Coca-Colas from their newly operating refrigerator — as a welcome. They were baffled when instead I opted for the warm, V. V. Putin-branded cherry juice that we stocked on the boat, with its cartoon likeness of the newly elected president emblazoned across the box.

In the decades since, it’s been an uphill battle dodging American-style global monoculture, whether in Kyiv or Kashmir, Tula or Tunis. And I’ve found it’s grown worse around holidays. Call me a scrooge, but I have no interest in trunk-or-treating on an 85-degree day in Carthage, mini-Snickers shipped through a diplomatic pouch from D.C. melting in the palms of so many tiny Spidermen and Elsas. I’ll be perfectly happy if my daughter never finds out the Easter Bunny exists, and then doesn’t really exist, and if she thinks that b’stilla and artichoke tagine are traditional Easter dishes for the rest of her life.

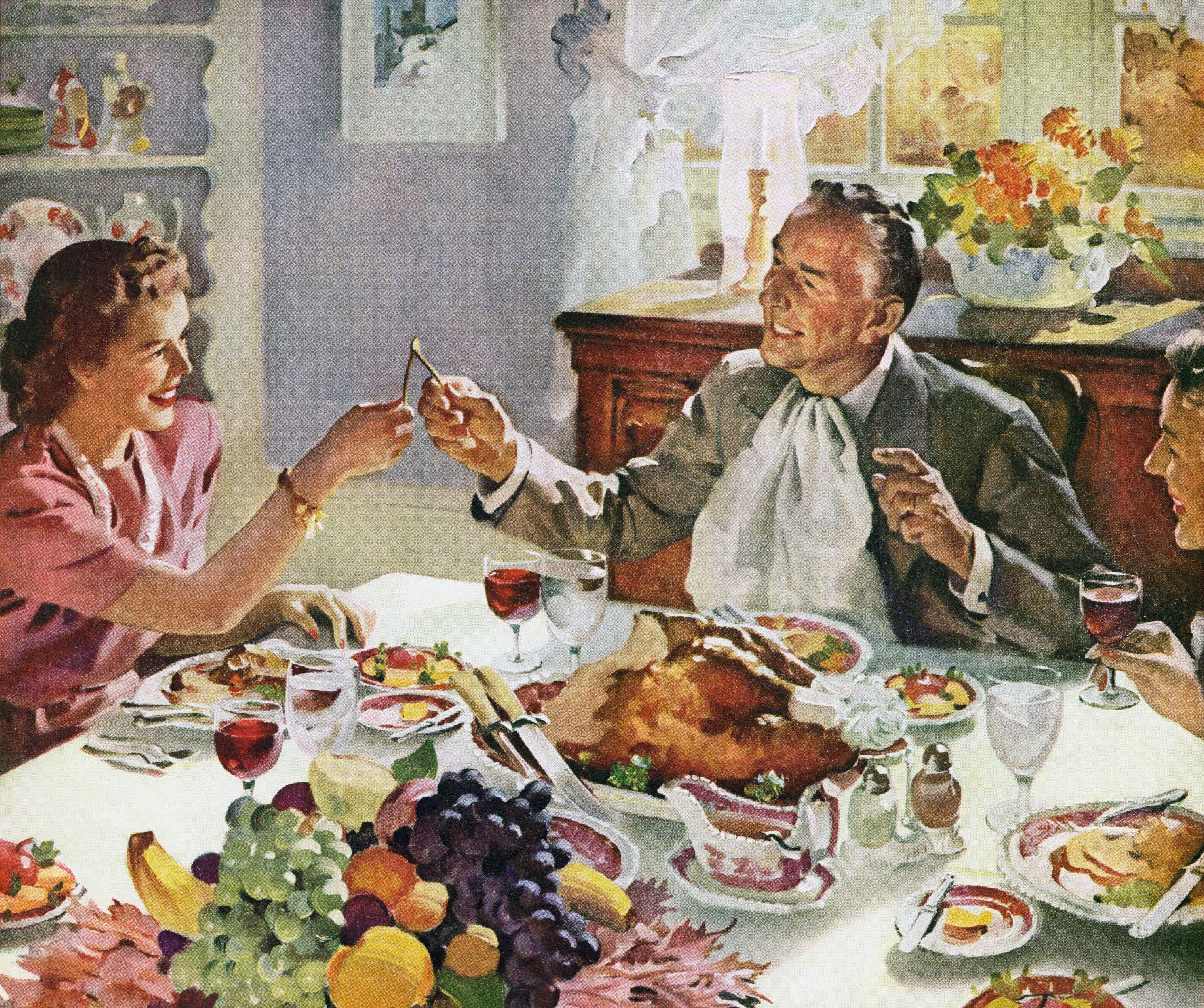

But Thanksgiving is different. Though consumer capitalism has eaten away at the edges of it (I’m looking at you, Black Friday starting on Thursday at 5 p.m.), Thanksgiving is still a holiday with two simple purposes — eat, and be grateful — and zero gifts or outfits to buy. It’s a holiday about family, yes, but also about throwing a tablecloth over a card table and borrowing some folding chairs so you can expand what family means, and invite others in to be warm and fed and cared for. In its essence lives a kind of perfected American Dream — everyone is welcome, there is enough for all, bring what you’ve got and add it to the spread — even if America has never actually lived up to such lofty ambitions, despite its abundance.

Plus, I love to cook, I love to eat and, above all, I love a challenge. Finding the right stuff for Thanksgiving in countries that have no idea what Funyuns are is a rare kind of thrill.

For a lot of Americans abroad, the biggest task is finding a turkey big enough to feed eight people at least three times over. There are tomes written on the subject, in New Yorker articles and expat Facebook groups alike. Heretical, I know, but for me, the bird was never the star of Thanksgiving — too easy to end up with turgid, dry, too bland or too salty meat — so I never fuss with trying to find a massive butterball that won’t fit into my tiny, unreliable rental oven anyway. In Moscow and Paris, I’d assign the guests I found least adept in the kitchen to pick up three or four rotisserie chickens en route and that was that. In other places, where turkey was abundant but oven space was not, we’d do turkey meatballs, or thighs burnished with lardo. To my mind, the true test of Thanksgiving, the abiding spirit and flavor and Americanness of it all, comes through the side dishes.

Just think about it. You can sit down at someone’s Thanksgiving table and almost instantly have a sense of where in America they come from. It’s not the turkey talking, it’s the cornbread dressing packed with green chiles (hello, Texas) or perhaps a Yankee-style sourdough version with oysters, or maybe it’s a green bean casserole oozing with the bechamel of the Midwest, Campbell’s cream of mushroom soup. Over the years, my side dishes have picked up bits and pieces from my various ports of call — I add chestnuts to my stuffing the way the most elegant American I knew in Paris did, or stir a bit of ras el hanout into my sweet potato puree — but at their heart, they embody the essence of my home in the mountains of Utah and the cuisine of my late grandmother, my mother and my aunt, who all cooked with rigor, passion and strong, comforting flavors.

To recreate that, certain conditions must be met. There must be sweet potatoes, not laden with brown sugar or topped with marshmallows, but their inherent sweetness allowed to shine with just a shimmer of butter; there should be a cooked green vegetable, whether brussels sprouts or green beans — but if it’s beans, they must be topped, regardless of whether they are steamed or sauteed or casseroled, with crispy onions; cranberry sauce, made from scratch with whole cranberries, not too sweet, that makes your mouth pucker when you lick it from the little silver serving spoon; mashed potatoes, of course (I married an Idahoan, so for the past five years I have forgone any notions that I might have about the mashed potatoes, and let the man live his heritage fully, usually with three types of dairy fat); a rich, smooth gravy; a sharp green salad to cut through it all, simply dressed, with fresh fruit like pears and a creamy cheese — blue or goat — to make it special; and my favorite, the stuffing, burnished on top and tender in the middle, chock-full of celery, onions, chicken livers and chestnuts, more butter than is reasonable, and infused with the most Thanksgiving flavor of all: sage.

Sage, with its earthy, ever-so-slightly medicinal quality that carries the fragrance of high mountain air and feels exactly like home for me, has been an uphill battle for many a Thanksgiving. For months I cultivated an anemic little plant from seed on the windowsill of my shabby apartment on the outskirts of Moscow, where dill is king and any other herb unnecessary; it yielded all of eight leaves, but each one felt like a miracle, and the stuffing was particularly delicious that year, a whiff of the Rockies in each bite. And while Tunisians love an herb, they prefer tender parsley or coriander; last year I searched for weeks in our local green market but no one ever turned up with sage.

After the cranberry fiasco, I was not about to lose another side to substitution. That’s when I remembered a secret my friend Rafram Chadad, an artist and dedicated cook, told me: Whenever he needed sage, he went to the Antonine Baths, in the Carthage Archeological site, where there were entire paths lined with sage and rosemary — which grow abundantly in the Mediterranean, but are used as fragrant ornamentals more often than foodstuffs in Tunisia. So the morning of Thanksgiving, I wrapped my baby in her carrier, slipped a pair of scissors in among the folds, and made the half-hour walk from my house along the coastline to the baths.

The Romans really understood the power of location. The massive bath complex, which was commissioned by Hadrian in the second century and finished by Antonius Pius, sits right on the coastline overlooking the bay of Tunis, with a view straight out to Bou Kornine, the mountain across the water where the ancient Phoenicians performed their sacrifices to the god Baal. That Thursday morning, the sky was a shocking cerulean, the sun gentle and warm, the entire complex, as it so often is, blessedly empty of tourists and full of birdsong. We strolled through the giant columns, in awe of the scale, before winding our way toward the back of the site where our quarry lay. Rows and rows of established, fragrant sage bushes lined a little walkway leading to an ancient underground chapel. I quickly snipped a few sprigs and stuffed them into the carrier with my baby — who, come to think of it, was about the size of a modest little butterball herself — and in that moment, I was overwhelmed with gratitude.

That’s the other thing about Thanksgiving. You cook and you eat and you make room at the table, but you also make room inside yourself for an exercise that too many have let slip by the wayside. The Thanksgiving tradition of expressing gratitude is an antidote to a more insidious American myth — that of the self-made man or woman. When we are grateful, we acknowledge that we are part of a larger whole, that we are connected, that in fact, no one owes us all this abundance, and yet it is here.

In my years hosting Thanksgiving around the world, I’ve found this exercise — going around the table to say aloud something for which you are grateful — revealed much about the people sharing my board. Folks in the humblest or hardest of circumstances often had the most to say. A friend who’d lost her younger brother to a tragic accident that year described her gratitude for the way she’d felt carried by her community in the wake of his death, and for the five sweet years she had had to relish his little light. I’ve only ever had one guest refuse to participate, a stiff European entrepreneur, a guest of a guest, who dismissed the exercise as “sentimental and too personal.”

It is sentimental and personal, and also essential to beat back cynicism, greed and despair. This year, as there is so much suffering and loss happening all over the world, in Gaza and Israel, Sudan, Armenia, Ukraine and elsewhere, I am feeling particularly grateful for the comfort and safety my family enjoys. I am grateful that my baby girl can run and play outside, with shrieks of joy and laughter ringing out from her little lips. And when she has run herself ragged, I am grateful that each night I can rock her to sleep before slipping a kiss on the tender part of her neck, just under her chin, and know that I can do the same tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.

Our Thanksgiving table this year will have both sage and cranberries — I potted a sage cutting earlier in the year and it has thrived, and my husband shoved a bag of frozen berries in his suitcase en route from the U.K. — and a motley crew of orphaned Americans and curious friends whom we will feed with joy and gusto. And when the moment comes, as the meal winds down and we’re picking at the edges of the stuffing tray while we wait for the pies to be sliced, we will go around the table and perform our ritual gratitude. The sentiments may be simple, but the effect is complex, larger than the sum of its parts. And as my guests pack up little bags of leftovers and head out into the night, I’ll sit down at my table, survey the remains of the day, and be filled with Thanksgiving.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.