On Oct. 9, 2023, just a day after the current war in Gaza began, the first evacuation order was issued for the neighborhood where I lived, near the Islamic University in Gaza City. The next day, on Oct. 10, the university buildings were destroyed. This was my university, the place where I had spent most of my time for the past two years. Now it was gone. It was not the first time the university had been damaged, but it was the most intense, and it was soon followed by strikes on all the other universities in the Gaza Strip. The university was not a military site but an academic institution, like thousands of others around the world. Education in Gaza has long been seen as a source of resilience; its institutions have been repeatedly targeted.

The destruction of Gaza’s universities has erased not just buildings, but entire futures. For students, it has turned years of study into uncertainty, forcing us to rebuild our hopes from the ground up. In tents and temporary shelters, learning has become both an act of survival and a way to hold on to the possibility of a different tomorrow.

Throughout my education, from elementary school through high school, I was always among the top students. In my final year of high school, or what we call “tawjihi” in the Arab world, I studied in the science stream. This year is considered the most important in any student’s life, as it determines your academic future and the major you will pursue at university. Despite the intense pressure, it was a wonderful year. I was surrounded by my friends — we went to school together, attended classes and studied side by side.

On the morning of July 30, 2022, I woke up to the result of all my hard work — my GPA score. I wasn’t afraid, but I couldn’t sleep the night before. My mind was spinning. At 9 a.m., my result came in: 89.7 out of 100. Such a high GPA meant I could choose to pursue any field of study at the university. I was overjoyed, and my family was even happier. That was what really mattered to me. That day, my uncle came to congratulate me and asked the usual question, not just among Palestinian families but, it seems, across the Arab world: “Engineer? Or doctor?” (In our culture, these are seen as the top two fields for science students.)

I didn’t know the answer. I was looking for a moment of rest, to sleep without thinking, but I couldn’t sleep. The question, “What will you study?” silently followed me. As the days passed, my friends began to decide: One would attend medical school in Gaza, another in Egypt. I asked myself, “Do I want to study medicine?” The answer was always no. I didn’t like the blood, the smell of hospitals or the stress of the profession. I thought about engineering, but I couldn’t imagine myself on that path either.

In mid-August 2022, I sat down with my mom, and she asked me in a completely different way: “What do you like to study? Where do you see yourself being creative?” This question touched something inside me. She wasn’t asking the usual question about social status or prestigious fields, but rather about my passion. I have always loved talking to people from abroad and watching movies in multiple languages, and I continue to be fascinated by English literature. I had long dreamed of studying in Britain. That night, I grabbed my phone and searched: Which major combined these interests? I found the answer: Translation. I had finally found myself. That night, I was able to sleep soundly.

The next day, I told my family about my decision. They hadn’t expected it, but it made them happy. My friends, however, weren’t so accepting, especially my close friend, Abu Hashem, who was preparing to study medicine in Egypt and didn’t want us to part ways. But I was determined to choose a path that was right for me, even if I was the only one on it. I joined the Islamic University of Gaza because it was the best university in this field. At first, I didn’t understand much of what the professors were saying, but I wasn’t alone — even my new friends were unsure. I knew every beginning was difficult, but I was enjoying the journey.

Every day, I would wake up at 5 a.m. to catch the university bus, even if my lecture was later in the day, because I couldn’t afford public transport. In the evening, I would return tired but continue to study. At the end of the first semester, I received good grades. Along with some friends, I decided to move to northern Gaza, even though I was deeply attached to my family, especially my mother.

We lived in a simple apartment — three students sharing a small space — and began a new chapter in our university life. I learned to rely on myself and fell in love with the streets of Gaza, which at night reminded me of the Paris I had only seen in pictures. I loved everything about student life, and the path ahead felt clear.

By the beginning of my second year at university, I had secured an academic exchange scholarship abroad. I used to start my day at the university cafeteria, then head to lectures, followed by a preparatory course for the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) exam, a global English test that checks your reading, writing, listening and speaking skills. It was exhausting, but enjoyable. I could feel myself getting closer to my goals day by day.

Wednesdays were the last day of university for the week, and the days I looked forward to returning to Rafah, in the south of Gaza, to see my family. The two-hour car ride gave me time to think about them and feel excited to finally be home, taste a bit of my mother’s food and sit with my father and siblings.

I returned as usual on Wednesday, Oct. 4. That Friday, I was still feeling that I missed my family, in addition to being exhausted, so my father advised me to stay home for another day and rest. On the morning of Saturday, Oct. 7, I woke up at 4 a.m., feeling better, and made myself a cup of tea — never imagining it would be the last cup I’d drink while feeling safe. At exactly 6 a.m., I heard rockets. I was supposed to leave in 10 minutes to catch the bus back to campus. In Gaza, we are used to military escalations roughly every two years, so I didn’t feel afraid at first. I thought it would be a brief round, like other times. But the sounds were different — more violent — and it wasn’t a usual start. I turned on the TV to see what was happening. What I saw was worse than I could have expected: a sudden collapse in the security situation, and a response unlike anything anyone had seen before. I realized this time Israel’s attacks on us would be far more severe.

That day marked the beginning of the end. Education was completely suspended: Universities, schools and institutions were closed, and my university was destroyed just two days later. Since then, the future for everyone in this small strip of land has remained uncertain. In the first few hours, I didn’t know what to do. Should I go back to my student housing in Gaza to get my belongings? Or should I leave everything behind and wait for things to improve? I had left everything that mattered to me — my laptop, my clothes and the certificates I had earned throughout my life. These things felt like pieces of my soul. How could I just leave them behind so suddenly? I called my roommate, who was still at our apartment, and asked him to bring my laptop and certificates if he could. When he eventually returned to the south, he brought them with him. I had lived through several wars and escalations, but I knew that what was happening now was entirely different.

The destruction didn’t stop at buildings; it reached the people themselves. Among those killed was Dr. Refaat Alareer, a scholar and writer who profoundly shaped the way I think and write. He was not only a professor of English but also a mentor. He taught me grammar and the importance of having a voice, of writing and of making an impact. He once wrote, “If I must die, let it be a tale.” On Dec. 6, 2023, he was killed, along with members of his family, in an airstrike. Yet, instead of being silenced, he became the story — a presence that lives on in every step we take forward.

Dr. Alareer was not the only one lost. Many professors from the Islamic University were also killed, including Sufian Al-Taih, the university’s president, a renowned physicist and mathematician who had dedicated his life to advancing science in Gaza. Professor Taih was killed on Dec. 2, 2023, among thousands of others. Education had stopped for the foreseeable future. Constant bombing, mass displacement and fading dreams left everything uncertain. I no longer thought about the IELTS exam — I thought about the next strike. Who or what would be hit next? Would I survive the night?

As the days went by, fear kept growing, and the bombing never stopped. With education on hold for months, I turned to volunteering to continue learning in some way. I helped distribute meals in UNRWA shelters and joined humanitarian initiatives run by local organizations. At 8 a.m. on the morning of May 6, 2024, the weather was unusually rainy. I heard sounds outside the house. I went out and found people gathered, with my father standing among them. I asked him, “What’s going on?” He told me, “The Israeli forces will invade Rafah by land.”

I was shocked. How would they enter a city with over a million displaced people? Where would we go? What choice did we have? No one knew. An hour later, papers started falling from the sky — evacuation orders for every area of Rafah, including ours. I gathered what I could of my belongings and my clothes. I said to myself, “Where are my books? Where’s my laptop?” But I was confused, shells were falling everywhere. I was overwhelmed and couldn’t concentrate. We took some things and left by car, leaving behind a whole home with all its traces of us.

In a moment of silence inside the car, amid the frenzy of our evacuation from home, my mother asked me, “Hassan, didn’t you forget your laptop?” I was silent. I had indeed forgotten it. I couldn’t answer. I left behind my study laptop, my books, everything I needed to study. I wanted to go back, but my father said, “It’s a limited operation … we’ll come back soon.” I didn’t know that was the last day I would see my home.

We arrived at al-Mawasi, the so-called “humanitarian zone.” But it wasn’t humanitarian. It was a land without life — just sand and sea. That evening, at 6 p.m., we were setting up the tent that we bought that day. Everyone was silent, working without words. My mother said to me with a sad smile, “Hassan, didn’t you dream of living by the sea? Well, your wish came true.” I looked out, not sure whether to laugh or cry. I wasn’t the only one who could no longer study. My little brother Mohammad didn’t take his school bag, my sister Malak had just started 11th grade and my sister Alaa’s university (Al-Aqsa University) had also been destroyed, along with many of its academic staff. That day, I felt like everything had ended.

In early December 2024, I began hearing about the possibility of universities resuming classes online. At first, I didn’t believe it. How could we study without electricity, without devices, without the internet? But in mid-January 2025, the Islamic University announced that it would restart classes through its Moodle platform. That was my turning point. I no longer just wanted to study abroad; I wanted to rebuild my path right here, with what I had. I enrolled my younger siblings, Mohammad and Malak, in a nearby school run by volunteer teachers living in the camps and housed in a tent, and I resumed my own studies online.

It wasn’t easy. I was living in a tent with no privacy, no quiet and a weak internet connection. Electricity was almost nonexistent. Once or twice a week, I would go to a cafe with a better signal in Mousaa, Khan Younis, about an hour’s walk from my tent, to download lectures and submit my work. At night, I studied by the light of my phone — until the battery died. There was no longer the tea I used to enjoy. There was no sugar, no gas stove — just firewood. So I settled for water. And still, I continued.

In translation classes, I connected what I was learning to the reality around me, working on texts about war, elections and famine. Studying poetry, I wrote sonnets that reflected my experience:

In war I found myself alone,

A name unheard, a heart of stone.

No light in sight, no end in fight,

Each breath I take, I steal from night.

The water cuts, it tastes like dust,

We drink and pray, because we must.

Our homes are ghosts of brick and flame,

We live in tents but call them “shame.”

For bread we crawl, for salt we bleed,

Each bite a war, each crumb a need.

They say they help, they send a box,

But blood still stains the aid that knocks.

A gift from those who made the sky burn red,

They feed us scraps, then count the dead.

We walk, we breathe, but not alive—

This war has carved a hollow life.

In one of the short story classes, we read “A Letter From Gaza,” written in 1956 by Ghassan Kanafani. It described exactly what we were living through. That story reconnected me to Gaza in ways I hadn’t felt in a long time.

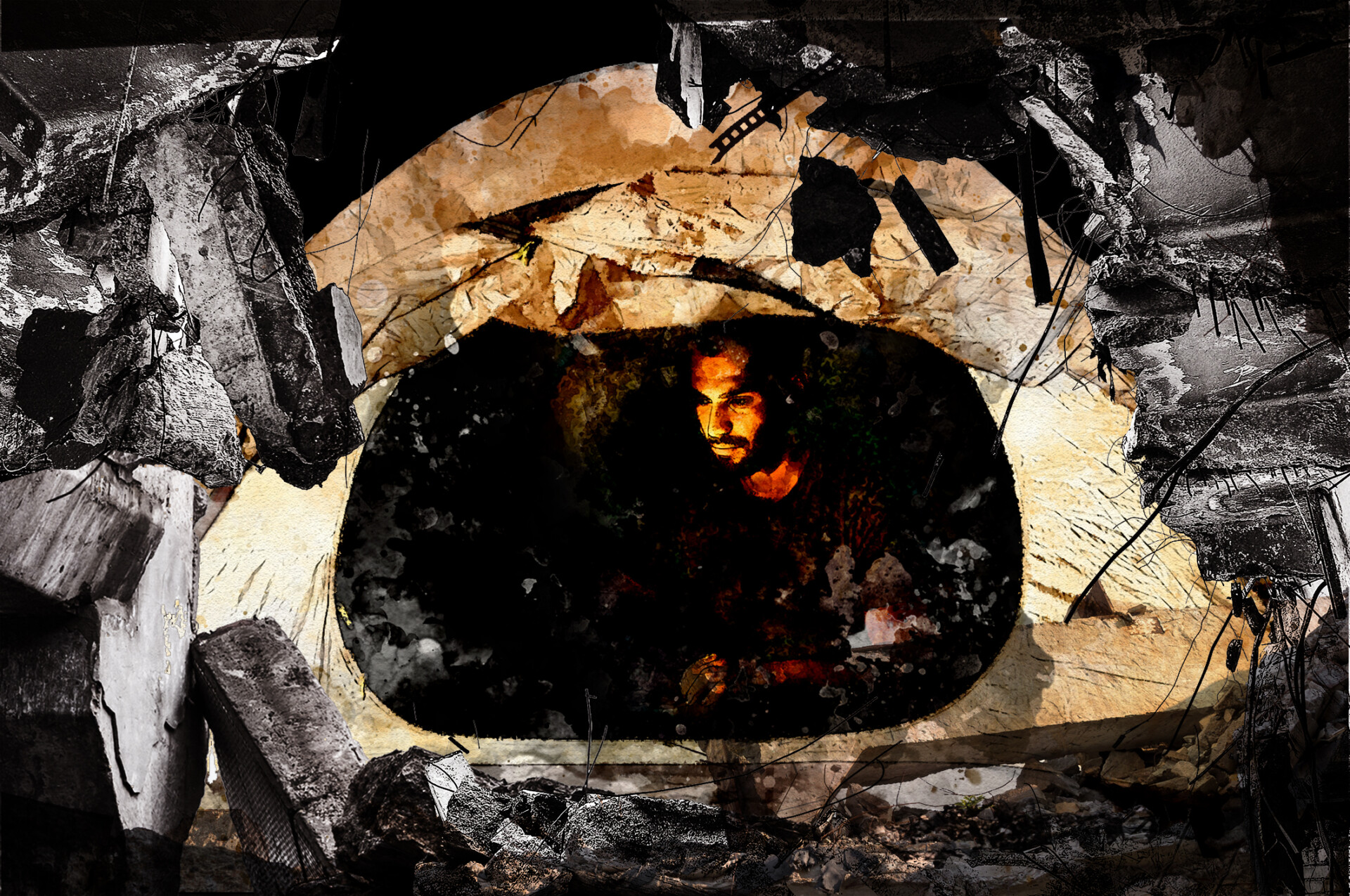

Recently, I had the chance to go north. I went to see the student apartment I used to live in — but it was gone. The entire building was a pile of ash. Then I headed to my university campus. A place that once reflected my hopes and ambitions had become a shelter for displaced families. The sound of lectures had been replaced by the cries of children, and the voices of classmates had turned into the groans of the displaced. The university buildings I used to walk through every day had become silent witnesses to the destruction of our future. I entered my faculty building; the door was completely burned. As for the library, families had burned its books to make fire for cooking. The graduation hall, the one I had always dreamed of celebrating in, was blackened, burned.

Despite everything, I found a way to make my voice heard. I began writing articles and publishing them with international platforms such as Mondoweiss, Palestine Chronicle and, most recently, here with New Lines. I also took part in international collaborative projects through my university, such as the Hope and Healing Project with Northumbria University, where one of my stories was featured on its homepage, and the project was highlighted in Babel Magazine in the U.K. I also contributed to the LINEsforPalestine project with the University of Malta.

Today, one of my dreams is to become a translator and public speaker, to tell the stories of my people, give voice to the unheard and speak the truth. I look up to Dr. Husam Zomlot, the Palestinian representative to the U.K., and admire his clarity, strong stance and unwavering commitment to defending our people’s rights. I also aspire to be a journalist who conveys reality as it is — without twisting the truth or embellishing it. I draw inspiration from journalists like the late Anas al-Sharif and Hind Khoudary, who risk life and limb to bring the world the unfiltered truth.

My current reality is living in a tent. No home, no campus life as I once had, no basic comforts, not even a cup of tea. But I refuse to let war decide my future for me. Education is not just a personal pursuit — it is resilience. It is a declaration that we will not be erased, and we will not be silenced. We will keep dreaming. We will keep writing. We will keep working for a better future.

Despite the genocide we are enduring, despite the horrors of famine, and despite all obstacles, I choose education. I choose to continue my path. As Mahmoud Darwish wrote: “One day, I will be what I want to be.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.