A small wall-mounted television broadcasting Syrian state programming flickered in the waiting room of the Syrian Ministry of Information, Department of International Press Visas. The year was 2005. We had been waiting almost an hour for our appointment, seated on plastic chairs placed in a row against a plain white wall. An assistant called us in: Dr. Wassim is ready for you.

A large, smiling man with slicked-back hair greeted us.

Sit, please. Yes, make yourselves comfortable.

My producer, Schams Elwazer, and I were asked about our assignment.

Will you be fair? Will CNN tell the world the true story of Syria?

Yes, of course, of course. We are journalists, and that is our job.

Dr. Wassim stopped talking. He stopped asking questions. He sat back in his office chair and looked at us like a principal would look at pupils sent in for bad behavior. An uncomfortable silence developed between us. It lingered, slowly expanding into an almost palpable entity. We waited for him to speak again. The silence made me particularly nervous; I was secretly recording our conversation on a 2004 model Nokia phone, which included new features like an integrated video camera. The quality was poor, but it was a useful and novel tool for journalists in the field. At that moment, I was furious with myself for taking the risk. The cellphone, in my jacket pocket, felt heavy and cumbersome. Would it click or beep or vibrate, exposing my stratagem? Dr. Wassim leaned forward.

“Remember that you are our guests,” he said. “And we are responsible for your safety. If you report something that is wrong, I can’t guarantee that we will be able to keep you safe.”

Yes, of course. Thank you, Dr. Wassim. We will report the truth.

It is how these meetings went. We already had a press visa, without which travel to the country for journalists wouldn’t be allowed. This was an additional, informal step, one designed to intimidate and muzzle. We had a license to film with the permission of the police state but were warned that expulsion was a constant threat. Perhaps worse. Don’t stray. Don’t test us. “Remember that you are our guests.”

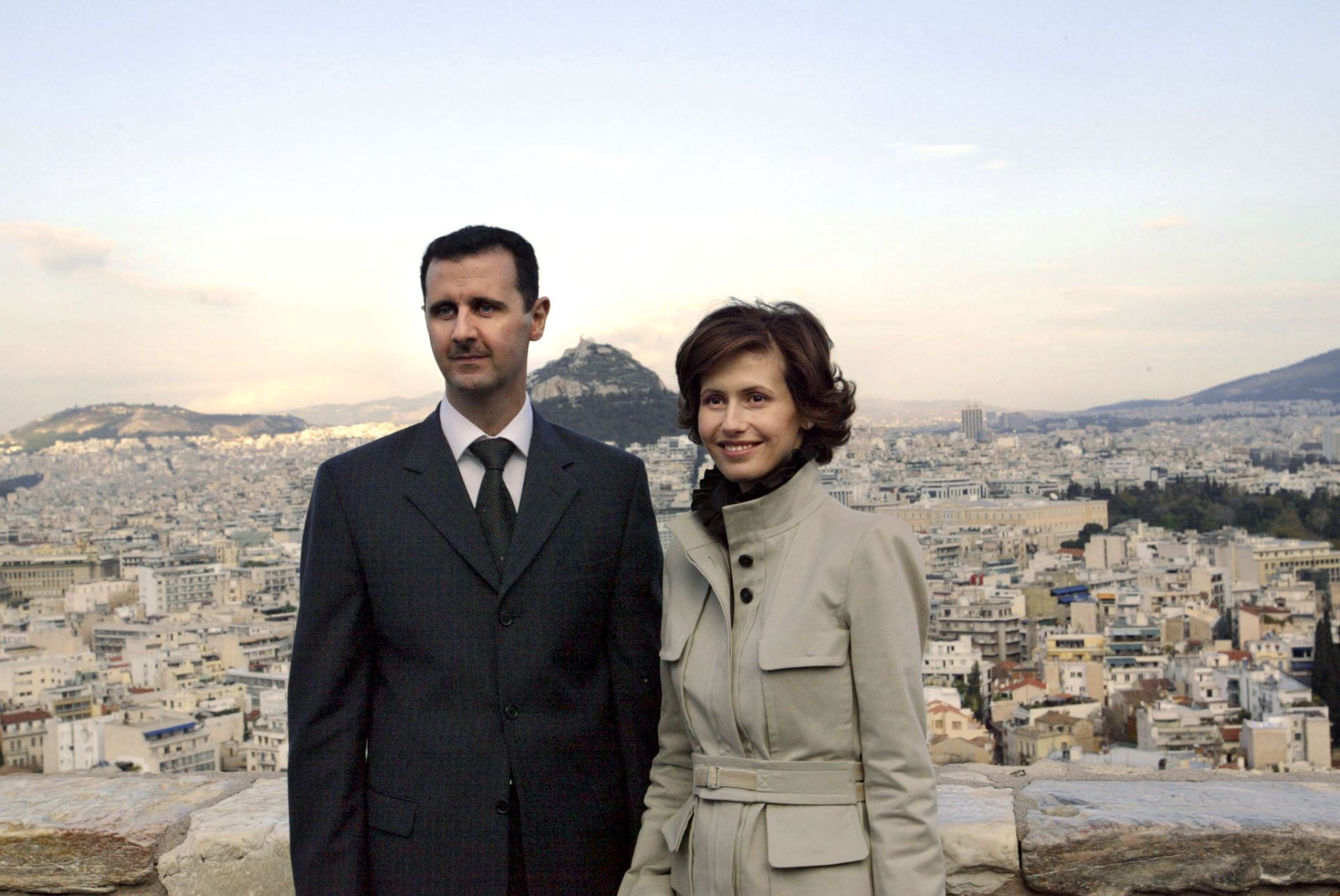

We took the elevator down to the ground floor of the imposing building in the Mezze District in Damascus and climbed back into a waiting van Schams had reserved for our trip. We were going to drive cross-country, starting in Damascus and then continuing north to Homs and Hama, ending our journey in Aleppo. The plan was to shoot a long-form story on Syrian youth. Over the past few years, the country had been slowly modernizing and opening its borders to tourists and foreign investment after decades of isolation under former President Hafez al-Assad. We wanted to document some of these changes through the eyes of young people living in three major cities. Hafez’s son Bashar, in power since 2000, with a glamorous wife raised in London at his side, initially seemed to embody a new era of freedom and opportunity. In interviews, he spoke with a lisp, in a soft, whispery voice. His receding chin and young age when anointed president made him appear more benign than his father and, in some ways, more approachable. He promised to liberalize the economy, to allow independent political parties and to loosen the state’s grip on the media, though always in vague and noncommittal terms. The young eye doctor was untested, but Syrians were so starved for change that they chose to believe that a new generation of leaders, who had lived and studied abroad, would be likelier to set them free because they had tasted freedom themselves. In some ways, the decision to believe in a new leader felt like blind religious faith: Even without evidence, there is sometimes comfort in the act of trust itself, however briefly the moment lasts.

“Did it record?” Schams asked. I pressed play. We could only make out every other word, so we immediately hit record again, repeating what we had been told in our own voices, filling in the blanks while we still remembered what Dr. Wassim had said almost word for word. We felt triumphant. We had a record of something that came across as a threat. We couldn’t use it in a news report, but it gave us a sense of having achieved something. The regime spied on its people. It disappeared dissidents. When Syrians spoke about politics, they whispered, even in their own homes. There was always a possible microphone hidden somewhere in a telephone receiver. The garbage collectors sometimes followed people when they moved. “Didn’t you work in our old neighborhood?” a novelist friend of mine once asked a street sweeper who appeared outside her new address. “They moved me,” he answered. Who moved him was not a mystery, though it needed to remain unsaid.

Aleppo was our last stop. Schams and I had driven 80 miles from Hama on the Damascus-Aleppo Highway, merging from the north with the Idlib-Aleppo Highway. There, greeting drivers on their way in, at the center of a huge 10-exit roundabout, was a rotating globe inscribed with the words “The World’s Oldest City.” It’s a boast many other Middle Eastern settlements have made, including Jericho in the West Bank, Byblos in Lebanon, Kirkuk in Iraq and Crocodilopolis on the River Nile (now known as Faiyum in Egypt). Like them, Aleppo claims to be the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world, dating back 8,000 years, ruled by the Kingdom of Armi, the Akkadian Empire, and the Hittites, all before most human settlements had even laid their first foundational stone.

From there, cars would either go straight to the central neighborhoods and the old city and its covered souks or veer left toward the newer Hay al-Sabil District, part of Aleppo’s development outside the medieval walled city in the early 20th century. The constant honking, the warm, dust-laced air, the sidewalks crowded with passersby, dodging street sellers crouched on the ground offering trinkets and baked goods and unshelled green pistachios: Aleppo had always felt at once familiar and foreign to me. Like a childhood friend I felt too awkward to fully embrace. The sounds of simultaneous calls to prayer from hundreds of mosques, broadcast over loudspeakers, in some cases competing with church bells in the Armenian district or the mainly Christian Aziziyah and Jdaydeh neighborhoods: Aleppo envelops and overwhelms. The covered souk, the largest in the world before it became a front line in the war between government forces and rebels in 2012, could take an entire day to navigate, from beginning to end. The journey through its alleyways was slow and winding through the gold market, the textile quarter, and to the stalls selling cheap plastic toys and racy women’s lingerie. Turn a corner and there are butchers hanging meat next to a baklava shop, turn right, turn left, go straight, get lost, even, in what was the city’s nerve center.

“Stop here,” I told our van driver. I’d noticed rows of men standing at the edge of a busy road with tools piled at their feet, apparently offering their services to anyone who would hire them. First, I spotted only a few workers, then dozens more. I addressed one man and was immediately surrounded. “If there’s no work, how can there be a future?” a young man named Fawaz Mohammed told me. Farhi Abdallah, age 22: “I’ve been here since dawn.” Hamid al-Ali: “I’m married and I have three children. I have no money for them.”

Most of the workers I spoke to that day had left Lebanon after Syrian troops, occupying the country for three decades, were forced to leave. The Syrian military had entered Lebanon at the start of that country’s civil war in 1976 but had overstayed its welcome after the end of hostilities. On Valentine’s Day, 2005, a bomb in a parked van exploded as the convoy of the former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri drove past. The impact of the blast was so powerful that windows shattered several streets away and killed 21 people in addition to Hariri. His assassination was immediately blamed on the Shiite group Hezbollah and on its allies in the Syrian intelligence services. Hariri had publicly spoken against Syria’s presence in Lebanon and so, many Lebanese believed, the Syrian regime made sure he could never speak again. The day workers in Aleppo told me they had been attacked in Beirut because they were Syrian. They said they had no choice but to leave, even if they only made a dollar or two a day back home in Syria. How many of these men were among those who later chanted, “The Syrian people will not be humiliated,” during the 2011 Arab Spring protests against the regime? How many were mowed down as they demonstrated?

That afternoon, in May 2005, after my work was done, I visited my grandmother Berine Gorani. After Hay al-Sabil, Berine and my grandfather, Assad, had moved farther west to Shahba, an even newer part of the city where more affluent residents built villas and low-rise residential buildings starting in the 1980s. Two aunts, a cousin, an uncle and my grandmother all lived on the same street in Shahba District after moving to the area in the early ’90s. Berine Gorani had been a widow almost 10 years, since my grandfather’s death in 1995, but was surrounded by family and visitors every day, as well as by a live-in housekeeper. She greeted me at the front door wearing a belted robe cinched at the waist over her tiny frame. In my conversational but unsophisticated Arabic, I told her about the story we were filming and about my job at CNN. It was rare for us to be alone, without other members of the family. I was so exhausted from my road trip that I could not stay awake. “May I just close my eyes for a few minutes?” I asked her. “Just here, on the sofa?” I don’t remember how long I was asleep, but it was dark out when I woke up with a blanket on me, still wearing my shoes. Nana Berine sat on an armchair opposite me. “I just wanted to make sure you were warm enough,” she said.

Issam, Rima, Randa, Lutfi. The names in my reporter’s notebook from that 2005 Syria trip come back to me like handwritten letters from another time. They are sent from a place that no longer exists. The country itself is gone, broken into pieces, emptied of half its inhabitants after a war so brutal that entire neighborhoods were blasted into fine dust. In 2005, though, there was still life: On the campus of Damascus University, Rima told me she was an English literature major who also studied at the High Institute of Music; Lutfi was a medical student; Randa, 21, was thinking of applying for a Fulbright scholarship. “If things don’t move the right way economically, we’re going to again be an isolated country, sitting in the middle of this world that’s moving forward while we are standing still,” said Issam. I reread the notes. Little details about each student scribbled in the margin:

Mom teacher.

Wants to work in banking.

Loves music.

Wants to get master’s degree in America.

In my hurried handwriting, I can see the seeds of the 2011 revolution, when a young, mobile, ambitious generation of Syrians witnessed the Arab Spring uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt and believed they, too, could ask for more freedom and opportunity. More dignity, as well. I am surprised by a quote from a 24-year-old Damascus University student named Jomana Abdo: “The young people deserve a change of this political system. It shouldn’t be like a royal system.” The public expressions of discontent had grown louder, just above the murmur of their parents’ generation. “Are you okay for me to put this on television? Everyone will see it,” I always confirmed. It was important that I heard them say it back to me. “Yes, I understand that this will be seen.” I did not want there to be any confusion. If the regime came after them, I wanted to absolve myself of any responsibility. After filming was over, I always returned to my home with the uncomfortable feeling of having left the people I spoke to behind to face any possible consequences alone. This aspect of my job infused me with guilt I carried with me at all times. I pass by, I witness, I report. They experience. Sometimes, they endure.

What the university students I interviewed didn’t know was that, through them, I was privately searching for clues about myself; for answers to questions that I wasn’t yet able to formulate. I was the daughter of Syrian parents from Aleppo, born in the United States, raised mainly in France after a divorce, and based, later in life, in London and Atlanta. I had spent a lifetime trying to feel like I belonged somewhere. Was I Syrian? Was I Arab-American? Was I, instead, French because I had grown up in Paris? If even a part of me felt Syrian, surely, I should see myself reflected in the people I met on that 2005 cross-country road trip: a sort of kinship through place of origin and ethnicity? After each interview, I realized that none of those labels felt right. I still felt stateless.

In my notebook, I wrote down the age, the number of siblings, the parents’ professions, the plans and dreams of each person I spoke to. Today, as I read my notes, I feel a quasi-physical pain knowing that the hopes of the university students I interviewed that day were likely never realized. The country’s youth would later be betrayed, shot, imprisoned or exiled. They were sacrificed.

Syria’s president, Bashar al-Assad, was then five years into the inherited presidential term of his dictator father, who had ruled the country like a crime syndicate for nearly 30 years. Hafez al-Assad took over as president in 1971 after a Baathist coup consolidated power in the hands of a few military officers from the Alawite religious minority. Though the country is majority Sunni Muslim, the Alawite sect, which had held outsize influence in the Syrian military before the coup, would place its allies at the top of a power structure that controlled what you could say, when you could say it and what the consequences were if you overstepped the mark. After Hafez al-Assad’s death in 2000, his son Bashar — then 34 years old — briefly allowed civil society to enjoy relatively more freedom. There were new political forums, public discussions about politics and the economy. Bashar, the young man who had studied ophthalmology in Britain, who had married an attractive JP Morgan banker from a bourgeois Sunni family: Would he be the country’s newest hero?

But dictators never truly soften for long. Their power is either absolute or it collapses. The strongman, like an abusive father, sometimes offers short respites, but only to crack the whip again. When every organ of the state is controlled by a single family, letting go in even one area means that the entire power structure will eventually crumble. Perhaps their existential fears aren’t entirely baseless. We have seen since what oppressed people do to their leaders, those who had sat in gilded chairs, presiding over mock cabinet meetings, sending dissidents to their deaths. They were hunted down, pulled out of hiding places and into the harsh light, beaten, insulted, spat on, and killed without mercy.

A year into his reign, Bashar al-Assad started jailing human rights activists, journalists and dissidents again. There was speculation that the regime nomenklatura had told the new president they could not guarantee that he would remain in power if he continued on this path of even limited reforms. Whatever the reason, the “Damascus Spring,” a short-lived period of open political debate and public demands of greater freedom, which had infused the intellectual elite with the romantic hope that their abusers had changed, was over.

The above is an edited extract from “But You Don’t Look Arab: And Other Tales of Unbelonging,” out Feb. 20 in the U.S. from Hachette Books.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.