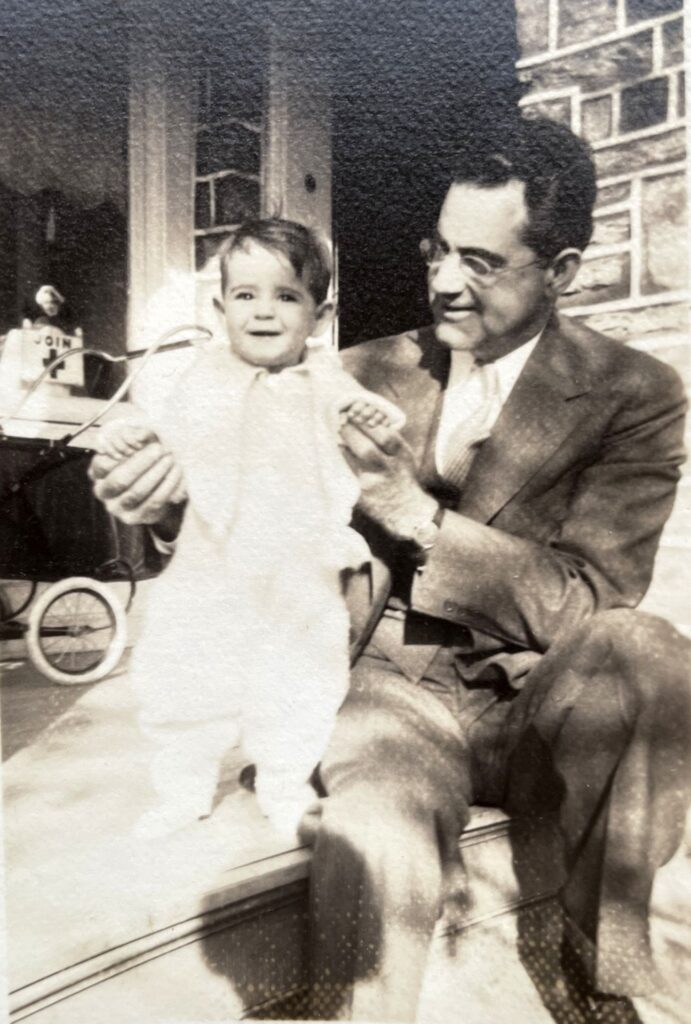

In 1916, a teenage immigrant from the island of Lesbos, Greece, climbed off a trans-Atlantic ship and presented himself to the U.S. border authorities in Boston. He had traveled by himself, leaving his parents and sisters behind as violence between Greeks and Turks escalated in his homeland. The boy was my maternal grandfather. Our family legend, always retold with a grin of pride at my papou’s audacity, is that although he was only 14, he convinced the guards that he was 16 and therefore legally able to enter the U.S. on his own. In later years, doubt lingered about exactly how old Papou actually was. He had brought no documents attesting to his date or place of birth.

This story tugs at me today, as inhibitions against the most extreme, even fascist, anti-immigrant rhetoric in America evaporate before our very eyes. Donald Trump’s invocation, at a December rally, of the specter of migrants “poisoning the blood of our country” can’t be dismissed as just an improvisational flourish; he has announced detailed plans, if elected, “to round up undocumented people already in the United States on a vast scale and detain them in sprawling camps while they wait to be expelled” from the country, as The New York Times reported in a story titled “Sweeping Raids, Giant Camps and Mass Deportations: Inside Trump’s 2025 Immigration Plans.” He means it.

But even more telling was the defense of his “poisoning the blood of our country” comment offered by Republican Rep. Nicole Malliotakis of New York’s 11th Congressional District. Speaking on CNN, Malliotakis invoked her own Greek and Cuban family history (“My parents are immigrants. … I have immigrant history too”) to authorize her claim that immigrants today are “poisoning America” with fentanyl and “destroying New York City” with crime. Trump, she insisted, was just naming this ugly reality — and signaling a core distinction between historical and geographical immigrant cohorts. Nor would most Democrats contest Malliotakis’ basic distinction between “legal” immigrants — who, like her parents and immigrant constituents (none of whom were born in Latin America, according to U.S. Census data), just want to “achieve their American dreams” — and “illegal” border-crossers who allegedly spread criminality and deviance on U.S. soil (and thus create “a problem at the border,” as U.S. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer euphemized, hedging his condemnation of Trump’s statement).

No one in our family or the Philadelphia Greek-American community where Papou became a revered leader would have called him an “illegal immigrant,” but he was. And unfortunately, Malliotakis is not an outlier. Despite our own immigrant past, many Greek Americans, along with other white ethnic groups from earlier waves of immigration, are either partisans of the Trump-led GOP or immigrant-wary Democrats.

What does it take for people who hold precious historical ties of culture and place, as do many Greek Americans, to gain a sense of shared fate and common experience with others whom they consider “foreign” or even “alien” threats, like the Mexican immigrants at whom the right directs so much vitriol today — while also acknowledging the differences between groups’ historical experiences: distinct types and magnitudes of obstacles and varying forms of courage needed to overcome them? How can recognizing rough but imperfect parallels between migrant pathways help us approach the divergences with more nuance and understanding?

These questions have perplexed people since at least the rise of modern nationalism in the 18th and 19th centuries. But they feel acutely urgent today, not only in America’s knife-edge milieu but also in post-Brexit Britain, where I now live, and countless other societies, including the rising number of European countries where anti-migrant politics have given the electoral edge to parties of the right. I have mulled over these issues since I began doing research with Mexican migrant workers over 20 years ago. I’m a political theorist curious about how migrants caught up in abusive work arrangements find the wherewithal to fight for themselve and the lessons of those battles for democracy itself. As I learn about Latino migration histories through my research, the stories and sense experiences I have imbibed as the product of Greek migrants continually recur.

It is very easy to overstate both the similarities and the disparities when comparing the fates of different migrant groups, especially given the thorny issues of race that entangle modern immigration. But it is also politically indispensable to venture such comparisons, fraught as they may be — especially right now. I want to illustrate how this can work by placing my family’s Greek-immigrant stories side by side with stories told to me by several Mexican migrants whose paths converged in a formidable, if fleeting, union battle against the world’s biggest meat producer, Tyson Foods.

In the summer of 1999, The New York Times and The Washington Post reported that the largest wildcat strike in recent U.S. history had just broken out at a massive slaughterhouse and beef-processing factory owned by IBP Inc., near the small town of Pasco in eastern Washington state. Fed up with horrifyingly dangerous working conditions and defying their own union’s unresponsive leadership, nearly 1,500 workers stormed out of the factory. Whole families camped outside the gates for six sweltering weeks amid the stench of cattle feedlots.

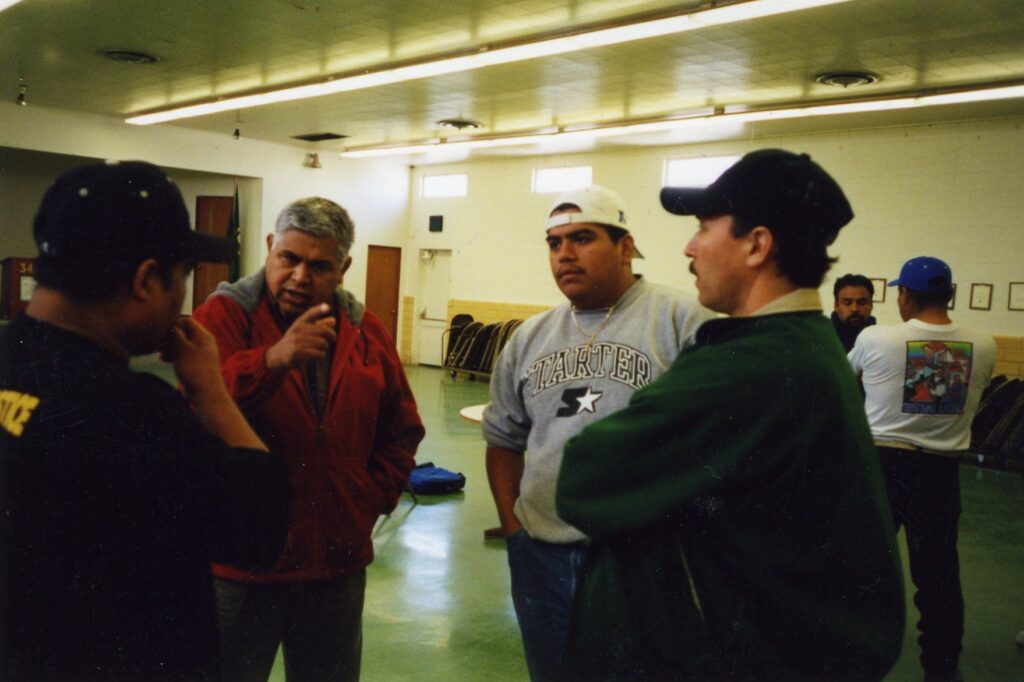

Eventually, the workers — almost all Mexican immigrants — wrested control of their local union from white leaders who were in cahoots with the company. They democratized their union, Teamsters Local 556, and launched a sustained attack on the company’s shocking labor practices. Tyson acquired IBP in 2001 and in short order trained its guns on the union. In 2005, the union lost a decertification election into which Tyson had poured its vast corporate assets. Yet that was only after an unprecedented battle with workers who had acquired startling resources of personal resolve and collective determination along the migrant trail.

These events occurred just 30 miles from Whitman College, where I was on the faculty and on the hunt for a new research project. Tyson’s global economic might, the bravery of the workers’ revolt and the national media’s interest piqued my curiosity, but so did the flicker of something more personal. This was a struggle waged by immigrants, and I wondered: What did these people’s experiences as immigrants have to do with their bold actions as workers? Were my family’s stories and histories at all like theirs, even though we were Greek and they were Mexican?

I began interviewing Tyson workers to gather oral histories as primary material for a book about what spurs migrant laborers to advocate for themselves under demoralizing and hazardous working conditions. The workers recalled their childhood years growing up in rural or urban Mexico. They explained how they had decided to leave for the U.S. and how it felt to leave behind people and places they loved (or didn’t love so much in some cases). They described harrowing, sometimes life-threatening treks across the U.S.-Mexico border, even in the 1980s before the border region became so intensively militarized. They talked about working in the fields, picking grapes, apples, strawberries — you name the crop, they picked it.

Then they told chilling stories of working at Tyson, where they quickly realized that enduring constant bodily pain and routine humiliation were basic conditions of earning their wages. And they shared how they had emboldened each other to stand up for themselves when they were mistreated and take charge of their local union so it would support rather than thwart those efforts. Those episodes often resonated unmistakably with events along their migrant journeys when they had been called on to rise above fear and display bravery, stamina and fellowship.

One day, my assistant and I interviewed a woman named Elvira Mendez at her kitchen table. She had worked at Tyson/IBP for a long time and helped lead the push for democratic reforms in the local union. As we talked about her memories of the past and present struggles, now and then one of her grandkids would run into the room. Elvira would pause to hand out a cookie or dry someone’s tears. When we were finished, she insisted we stay for a bowl of pozole, a Mexican stew thick with corn hominy and chicken — best enjoyed with a fresh lime squeeze and a sprinkle of oregano — that I hadn’t tasted before moving to this heavily Mexican region. But watching Elvira through the steam of the pozole, I felt a deep sense of the familiar about her ways with children, and with food. I looked at that dish of lime and saw, in my mind’s eye, the lemon wedges that my yaya (Greek for grandmother) always had on the table.

Later, in a moment of hasty self-disclosure as I was catching up with the union’s leader, Maria Martinez, about the interviews, I blurted out: “You know, I love these conversations because the workers remind me of people in my family. There must be real similarities between Greek and Mexican immigrants’ experiences.” Maria looked me right in the eye and responded, without hesitating or smiling: “No, Paul. It’s different. It’s not the same. It’s really different.”

One of Maria’s virtues as a leader was her willingness to speak directly about controversial matters. She rebuffed me briskly, and I felt stung. But later I began to see what I think she needed me to grasp if I was going to be of any use to the workers’ cause, as I hoped to be through my research, teaching and community activism. Maria was warning me that if I didn’t recognize what was different about Mexican immigrant pathways today from the migrant passages of my ancestors, I simply wouldn’t understand what the struggle at Tyson was all about.

This bracing lesson, however, didn’t stop the flow of parallel images in my brain. And I think there is something worth holding on to in that impulse to see one group’s migrant experiences reflected in those of another, so long as this doesn’t prevent us from attending to what’s “really different.” With that in mind, let’s consider: How does my family’s story compare to those related by the migrants I met in the midst of the struggle against Tyson?

The central character in our family’s narrative has always been my papou, Nicholas Padis. Papou was born in a village near Mytilene on Lesbos. According to an anecdote in a family cookbook created by my cousin Poppy Gregory, when Papou “was a little boy he drank his milk straight from their mother goat. He would just get under her and suckle. He grew up to be a doctor, and certainly always looked well fed.” Poppy makes it sound like it was no big deal for Papou to go from being an island child whose family kept goats to a well-fed doctor. Yet a lot of hardship, loss and struggle intervened for this individual, whose life began in the village at the turn of the 20th century and ended, in 1982, with his portrait hanging in the physicians’ library at Philadelphia’s Lankenau Hospital, where he was a distinguished staff member.

Things changed for the worse for Papou’s family when tensions escalated between Greeks and Turks just before World War I. This was still several years before the catastrophic burning in 1922 of Smyrna by Turkish forces, which drove hundreds of thousands of Greeks (and many Armenians) into exile, and the 1923 official Greek-Turkish population exchange. Yet a process of ethnic cleansing, triggering mass population movements and refugee flows, was already well underway: flushing Greek-speaking Christians out of what would become the Turkish republic’s territory and ejecting Turkish-speaking Muslims from lands over which Greece was assuming authority, including many Aegean islands. My older family members’ memories are hazy on the details although mercifully free — I’m not sure why — of the tendency to demonize Turks that often features in Greek remembrances of this period. But essentially, amid growing civil disturbances and violent episodes, as ethnic-nationalist fervor mounted and the Ottoman Empire contracted, Papou’s family found it necessary to abandon Lesbos.

It was decided that Papou would travel all by himself to America even though he was only 14. Somehow he made it to Boston, where his famous encounter with U.S. immigration control took place. They evidently let him in without documents, but they asserted their prerogative in another way quite typical at the time: they shortened his surname from Pathiatis to Padis. As if to say: In you come, but we decide how you’ll be heard and seen here in America, so we’re giving you a more “normal” name.

Papou could be very persuasive, as the tale of his arrival illustrates. This is the same fellow who, 22 years later, was determined to go see President Franklin D. Roosevelt speak at the 1936 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. Papou presented himself at the door with no ticket, but as a doctor, full of gravitas, probably sporting his signature bow tie. He was escorted to a front-row seat, no further questions asked.

Courage, audacity, tenacity: Those are the personal qualities that I have always heard associated with my grandfather and his immigration story. Also, as in so many immigrant narratives, unrelenting hard work. Papou started working two jobs in Boston, laboring by day in a tire factory and at night as a waiter in a restaurant frequented by Calvin Coolidge, who was fond of being served by “Nick,” the young Greek. In little time and still a teenager, Papou made enough money to pay for his parents and sisters to join him in the United States. He even saved enough to set his father up with a small shoe repair business in Boston. A few years later, Papou was awarded a scholarship to attend Boston University, then attended medical school and launched his career as a physician in Philadelphia. More than an aspiring professional, he also had a zest for strengthening the community. He and my grandmother co-founded a civic organization in 1936 to encourage young Greek Americans to go to college, and it still thrives today. When a new suburban Greek Orthodox church opened its doors in 1960, Papou flourished the honorary key.

I know nothing about what my Papou’s voyage to America was like, but I do know that when the family became uprooted in the years just before he left Greece, things were dangerous. Resting on the mantelpiece of our London flat is a cherished object that survived that period: our family icon. Painted several hundred years ago in traditional Greek Orthodox style, with gold leaf that shimmers in candlelight, the icon shows St. Simeon’s joyful response as the baby Jesus is presented at the temple. After briefly moving to what is now the Turkish mainland, the family ended up being force-marched back to Lesbos. Papou’s parents worried about how to keep the icon safe from people who might steal or destroy it along the way. So they wrapped it in a blanket, put it on Papou’s young shoulders, and told nosy fellow travelers it was a mirror, which earned them mockery and derision: “How vain, those Pathiatises are! Here we are, fleeing our homes, bringing only what we can carry, leaving everything else behind — and they care so much about their precious good looks!”

What gets hidden — what goes into hiding — when people immigrate to the United States? For us, it was an inconvenient syllable in a “long” Greek name, in a culture that favors names like Smith and Brown. It was my Papou’s age and status as a child, and in a broader sense his youth itself. It was an old family icon, later to shine forth with all its somber beauty but battered by the years and miles. It was also, I learned to my astonishment when I was about 30, my parents’ hushed-up legal marriage at a New York City courthouse, six months before their “official” 1960 wedding at St. George’s Greek Orthodox Church in Philadelphia. My father was a Greek immigrant, whereas my mother was born in Philadelphia to Greek immigrant parents. It seems that at about the time he met my mother, his visa was running out and U.S. immigration law, based then on national origin quotas skewed to favor northern Europeans, made it tough for Greeks to become permanent residents.

The Mexican people I interviewed in Pasco shared their own stories of things being hidden, and going into hiding, coming to America. The theme resonated, but the details were significantly different, and they speak to the frankly greater courage, audacity and tenacity needed at moments when hiding things meant survival. There was the money to pay for a family’s cross-border passage that a mother sewed into the hem of her skirt to conceal it from the “coyotes” — the smugglers — who brought them over. There was precious food and water, revealed and shared when families were cooped up in way stations with only dirty water to drink and no idea which side of the border they were on.

Mostly, the stories were of people having to hide themselves from fearsome danger, often showing great mettle, generosity and clever resourcefulness. One young father, Pedro Ruiz, told me how he and a fellow traveler had crossed the border in the trunk of a car after they had left their home villages and family goats in Mexico. The air was tight, the heat was intense, the road was rough, the car was racing along — and the other man started to panic. Pedro kept his nerve and gently calmed the other fellow, repeating: “You’re going to make it, this is so you can make it.”

Elvira struck a similar chord when she told me about crouching in a big crate of apples, heart pounding, as immigration officials raided a packinghouse in central Washington where she was working. Later that afternoon, she climbed out, tossed her tell-tale, broad-brimmed farmworker’s hat in the bushes, put on lipstick and strolled confidently out of the facility, head held high. She was hiding in plain view, you might say. Yet in this act of slightly disingenuous self-assertion, she was also confirming for herself and others that she had a right to be there. Pedro had done likewise during an Immigration and Naturalization Service raid at a warehouse near Los Angeles. When the agents showed up, a co-worker froze in terror and started nervously coughing. Pedro kept his cool, dispatched his colleague to the bathroom and stayed at his post acting like someone who had a serious job to do and didn’t appreciate distractions. The agents never questioned him, although that day they took away 40 people.

Pedro and Elvira were protecting themselves, concealing themselves, but also visibly asserting themselves by “passing.” And I see here more than a passing resemblance to the precocious teenager from Lesbos who assures the border agents he’s two years older than he really is and walks on, into the streets of Boston. Or who makes Roosevelt’s convention ushers think it’s obvious that, of course, “the doctor” should be shown to his seat. Yes, divergences are immediately noticeable, but let’s not rush too quickly past the correspondences.

These rough but real parallels evoke the courage that it takes for immigrants to bend the rules and mollify their enforcers with dignity and pluck. It’s a matter of having the nerve to enact “the right to have rights,” as political theorist Hannah Arendt put it, precisely when the law and the state tell you those rights are not yours to claim. There are certainly ways that we Greek Americans, and many others who identify with immigrant roots in earlier eras, should see more than just traces of the familiar in how recent immigrants from Mexico have protected and advanced themselves. This may require being more honest with ourselves than we might prefer about not just the easy-to-celebrate heroic themes — long hours worked, upward mobility, a passion for education, but also the more ambivalent chapters of our migration stories — laws circumvented, disrespect mutely suffered, deceptive appearances fashioned under watchful eyes.

Again, what about the differences?

A poster from the National Day Laborer Organizing Network hangs on the wall of my study with the slogan, “Courage > Fear.” I recently wrote a book about the work experiences and community-building efforts of day laborers, who are central to the American residential construction and home improvement industries. On a person-to-person level, one might say that these mostly Latin American migrant workers keep people’s gardens tidy and houses sturdy while meatpackers make sure there is plenty of high-protein food for the family dinner table.

The day laborers’ motto that “courage is greater than fear” suggests how we might further understand what’s “really different,” to recall Maria’s admonition, about Greek and Mexican immigration experiences. To see the differences, you have to ask: What exactly is there to fear, when you’re an immigrant? And what kind of courage do you need to face down that fear?

War-time conditions during a period of accelerating imperial decline made things dangerous for my great-grandparents and Papou in Greece. And I am sure there were other hazards on the ship across the Atlantic. Yet my ancestors did not face the everyday menace of violence from the state or private individuals when they arrived. Greeks usually did not encounter such threats, although they were at times targeted by the early 20th-century Ku Klux Klan, which considered Greeks “not exactly white.” They also faced mainstream, racially tinged prejudices for not being from the right part of Europe — or not from Europe at all, or not “modern” enough, or too prone to take life easy in the blissful Mediterranean sun, as my cousin, archaeologist Dimitris Plantzos, argues in his witty critique of postwar movie and pop-song images of Greece. As Dimitris argues, the racializing tropes associated with Asians and Middle Easterners that Edward Said analyzed as Orientalist devices have been avidly applied to Greeks, too.

But the cultural prejudice and institutional devaluation faced historically and even now by Greek immigrants are quite different from the violent hostility — the systematic, deadly, dehumanizing domination — that has confronted Mexicans who migrate north. In part, this difference relates to America’s entrenched social hierarchies of skin color. Popular parlance has often described Greeks as “swarthy” or “olive-complexioned.” This proved rather inconvenient for 18th- and 19th-century Brits and Germans who wanted to identify Greece and all its “ancient glories” with the cultural heritage of those who were more likely to be fair-skinned and fair-haired, the better to justify colonial and imperialist rule over people with darker-hued bodies in Africa, Asia and elsewhere. Yet although historically deemed not quite white, Greeks have essentially been amalgamated to the bland and less freighted category of “white ethnics.” This classification carries racial residue, but it does not structure whole systems of economic and political power.

By contrast, Mexican-origin people today bear the legacies of skin-based colonial categorizations that were finely differentiated and methodically deployed to govern diverse areas of social life including marriage and work, before being homogenized in the 19th century into a (more) uniform brownness signifying racial degradation. Under the rule of Spanish-colonial “pigmentocracy,” darker skin color and other traits marking Indigenous or African ancestry were explicitly invoked to assign people a lower social status. Following the subsequent consolidation of racial types in modern times, to be labeled a “Mexican” by whites in the U.S. has become a matter of whole-cloth stigmatization. It implicitly references traces of indigeneity, Blackness or Black proximity as defining a person or group in toto rather than by degrees.

It also enlists skin color in erasing distinctions of national origin, insofar as the epithet “Mexican” is thrown at “Latino” people from places as far from one another, geographically and culturally, as Nicaragua and Peru. And it legitimizes violence that is routine rather than episodic, as much on the open turf of national borderlands as behind the dreary walls of maquiladoras and packinghouses.

When Pedro Ruiz finally emerged from the trunk of that coyote’s car, he was shot at as he ran through the border hills. The men wielding the guns weren’t U.S. Border Patrol agents but armed vigilantes. The private militias that take the law into their own hands to keep Mexicans out of Arizona are tolerated by the government and lauded by Republican officials. When that’s what you have to fear, it takes a different kind of courage to keep going, hoping and working, compared with the fortitude my ancestors had to show. And it doesn’t make the latter any less honorable to point this out.

Things are worse now than they were 30 years ago when Pedro crossed over. Now, more U.S. private citizens near the border are armed with guns, intent on using extrajudicial violence to keep Mexicans (and Central Americans) out — a chilling new chapter in an ongoing story of racial violence in the American Southwest. Despite Republican efforts to blot out inconvenient facts from school textbooks, it is still — fortunately — common knowledge that countless Black people have been lynched throughout U.S. history. Yet few Americans are aware that lynching Mexicans was common practice in the Southwest, especially in Texas, in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Thousands of Mexicans were tortured and murdered in these unspeakable acts of terrorism. And while it is important to appreciate the historical differences between Black and Mexican experiences of lynching, both stemmed from organized systems of violence involving cooperation between private groups and public law enforcement. Most Americans today think of the Texas Rangers as a baseball team, but in the history of that region, the Texas Rangers were government forces that specialized in lynching Mexicans and persecuting Mexican communities with ruthless brutality.

I’m not sure what would have happened to Papou if his ploy to pass as a 16-year-old at the Boston border hadn’t worked. Officials at the time commonly detained unaccompanied children, people with symptoms of illness and others deemed likely to become “public charges.” I do know, though, that he almost certainly would not have been locked up for more than a few days or weeks, or told to wait for an immigration court to consider his case with no access to counsel and no hearing date given. Nor was he branded a criminal for lacking proper documents. All these things were precisely what Pedro Ruiz, Elvira Mendez and their co-workers had to fear when they came to America — that, and the legacy of the Texas Rangers. And that meant mustering quite another level of bravery and resourcefulness.

These days, plenty of Americans would get irritated or downright angry reading these reflections. They might retort: Sure, things are “really different” for Mexican immigrants compared with Greeks, but that’s not because Mexicans are under threat, it is because they are invading America! What choice do Arizonans have but to grab a gun when the government lets violent criminals swarm into our country with no consequences for breaking the law? Damn right, we need to lock these people up, whether they are adults or 14-year-olds whose parents send them on their own, because they are overrunning our towns and overcrowding our schools. If Mexicans have a lot to fear, this argument goes, it is for good reason. Nor should we think these are fringe views. Once marginal, the rhetoric of “invasion” now dominates ordinary Republican talk on immigration.

These were common excuses a century ago for the lethal violence of the Texas Rangers, and they were no more valid then than they are today. A Stanford economist found in July 2023 that since 1880, immigrants have been less likely to be imprisoned than U.S.-born individuals, thus confirming what other analysts have consistently found. In the days when the Rangers dispensed the state’s “justice,” Mexican people were killed, harassed and stereotyped to keep them in their place. That meant doing backbreaking physical labor in the fields, especially after the abolition of Black slavery made farm labor harder to get for American agribusiness. The combined powers of persuasion and coercion — culture and economics backed by military force, or “hegemony” in Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci’s sense — ensured that Mexicans would stay docile. Academics from prestigious universities even testified to Congress in the 1920s that Mexicans were suited to farm work “by nature,” with bodies made for hard labor, minds ill equipped for intellectual tasks and volatile temperaments needing firm discipline by their social betters.

Gramsci also argued that ordinary people could find the kernels of transformative “good sense” in their own “common sense,” acquired in local communities and material experiences of work. The key was for leaders among the people to encourage careful thinking about how history had shaped people’s assumptions about their own and others’ identities. The legacies of racial violence and the growing muscle of today’s racist right wing are daunting and dispiriting. But we should not underestimate the potency of immigrant common sense — expressed through our immigrant family stories about love, courage and work as strangers in America, and refined in the glow of history — to foster more good sense in these disturbing times.

Papou knew about hard physical labor from that tire factory and all those nights at the restaurant as a newly arrived immigrant. Yaya’s mother knew it her whole life. Her name was Anastasia Evangelides, and we called her “Big Yaya,” although she was barely 5 feet tall as an elderly woman. Big Yaya worked for some 30 years in a Johnson & Johnson factory in New Brunswick, New Jersey, where Yaya’s family had settled when they fled Asia Minor. Big Yaya lived with Yaya and Papou, and when I went over to their house she was always a bundle of energy. I would find her either upstairs sewing clothes in her room or vigorously stirring a pot in the kitchen, unless Papou was in there curing his olives or stewing squid with red wine and peppercorns, exuding a pungent aroma that’s still fastened in my olfactory memory.

But one day when I was over there, Big Yaya was just tired. She was sitting quietly in the breakfast room, her back was hurting and her arthritis was acting up. All those years at Johnson & Johnson, Yaya told me, had made Big Yaya’s muscles and joints very stiff. So, I gave Big Yaya a back rub, which I had never done before: She had always been the one patting me on the back or hoisting me onto her knee and clucking, “My boy, my boy!” She didn’t say much else that I understood — she spoke little English. I was utterly shocked by how knotted up her back muscles felt. They didn’t feel like muscles at all, more like hard pieces of wood. I remember her face scrunching up as I tried in vain to get those sinews to soften.

Some 20 years later, I was sitting with Elvira at her kitchen table and she was telling me how processing beef had affected her body. Meatpacking is America’s most dangerous job. When I did my research in Pasco, Tyson’s plant was in the worst quartile of America’s meatpacking facilities for workplace injuries and health problems. Each year, 1 in every 4 workers at this plant became so seriously injured or ill from their job that the company let them miss work (according to federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration data). Among the most common injuries in meatpacking are musculoskeletal disorders that cause workers’ muscles and joints to swell or lock up. This happens from making repetitive motions at frantically high speeds, minute by minute, hour upon hour, cutting into half-frozen hunks of cattle carcasses with no time to sharpen your knife when the blade dulls.

Elvira explained how she recently had to switch from her regular job to “light duty” because of a muscular health problem. She held up her arm and I was appalled to see that it had swollen to twice the size of the other arm. I could tell, just by looking, how seized up the muscles were. A child came running in and Elvira gave the boy a caress on the head. Then she told me how, because of her injury, she couldn’t pick up her grandkids anymore, even the little ones.

There is factory work that hardens your body and toughens it but also makes it hurt and binds it up, especially when you’re 80 years old like Big Yaya. Then there’s factory work that distorts and disfigures your body — work so painful that your sense of “normal pain” changes forever and you can’t sleep, as was generally the case for Elvira and her colleagues. Work that physically interferes with the ordinary gestures through which family members express love and care for each other.

Why do America’s major meat companies run production lines at speeds that injure workers? Why isn’t manufacturing food for “our” families being done in ways that are healthy for workers and their families? Most immediately, it’s because American consumers expect cheap beef to be there whenever and wherever they want it, whether in a rich or poor neighborhood, in an airport or train station, on the highway or by the beach. More fundamentally, big meat firms earn big profits by fostering that assumption. And to sell the beef cheap, Tyson and its competitors drive employees to churn out massive volumes in very little time. Until I met these workers, I never thought about how fast food restaurants could feature a dollar menu. Such a bargain, it seemed! But 99 cents is not the real cost of that burger. The full cost also has to include immigrant workers’ physical health and emotional damage.

What motivates people to fill out an honest ledger? To register how that “Cheeseburger > 99¢” — and how “Courage > Fear”? To see how vast the costs paid by immigrants in our racially structured food system are, and how steely a person’s nerve and resolution need to be in response? This is where I think making risky comparisons between immigrant family histories is so important. People can start to think and feel differently about who bears which costs of our common life when they take the chance of telling and listening to stories of different immigrant groups — together. This makes it possible to sense the profound resonances between, for instance, Greek and Mexican immigrant experiences as well as the jarring ways that such experiences are “really different.”

Maria was right to insist on the disparities. Yet by also noticing the things that are not entirely different, we can tap into vital sources of curiosity and common feeling. We might then be moved to ask why the distinctions are there and what we can do about them when they’re not just differences but also injustices that implicate us because of both past and present circumstances.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.