I sit down again in my exile in London. At the writing table, I close my eyes. Wars are raging across the world. I remember my country Syria from afar. I see the last 11 years in a flood of memory, with so much pain, with so much loss, and with a sense of injury and vulnerability.

What has happened? How have we reached this point? What story to write about Syria? How to write it? Why continue writing about Syria? And above all, who has the right to write?

I close my eyes again and think of my city, Homs. I left Homs on Nov. 17, 2011. I have not returned to Syria since.

While I’ve been living in the comfort of this tough yet wonderful and diverse city, images of Homs have never left my mind. In my exile, I see it in ruins, a city where over half of its neighborhoods have been destroyed, a city that became known as the Capital of the Revolution. Thinking of Homs in exile makes my heart ache with the thoughts of all those who lost their lives in this war, and all the living, whose everyday life is a war in itself: their faces, their places, their names, their kindness and their generosity.

As I walk in London, everything that is ruined reminds me of home. Seeing a demolished building transports me in time and space from London to Homs. I stop immediately to look at the ruins with sadness and shock but also with an image that I have finally returned to Homs. The rubble in London reminds me of the ruins of my life and the ruins of Homs. Everything that is collapsed, demolished, abandoned or broken makes me think of Homs.

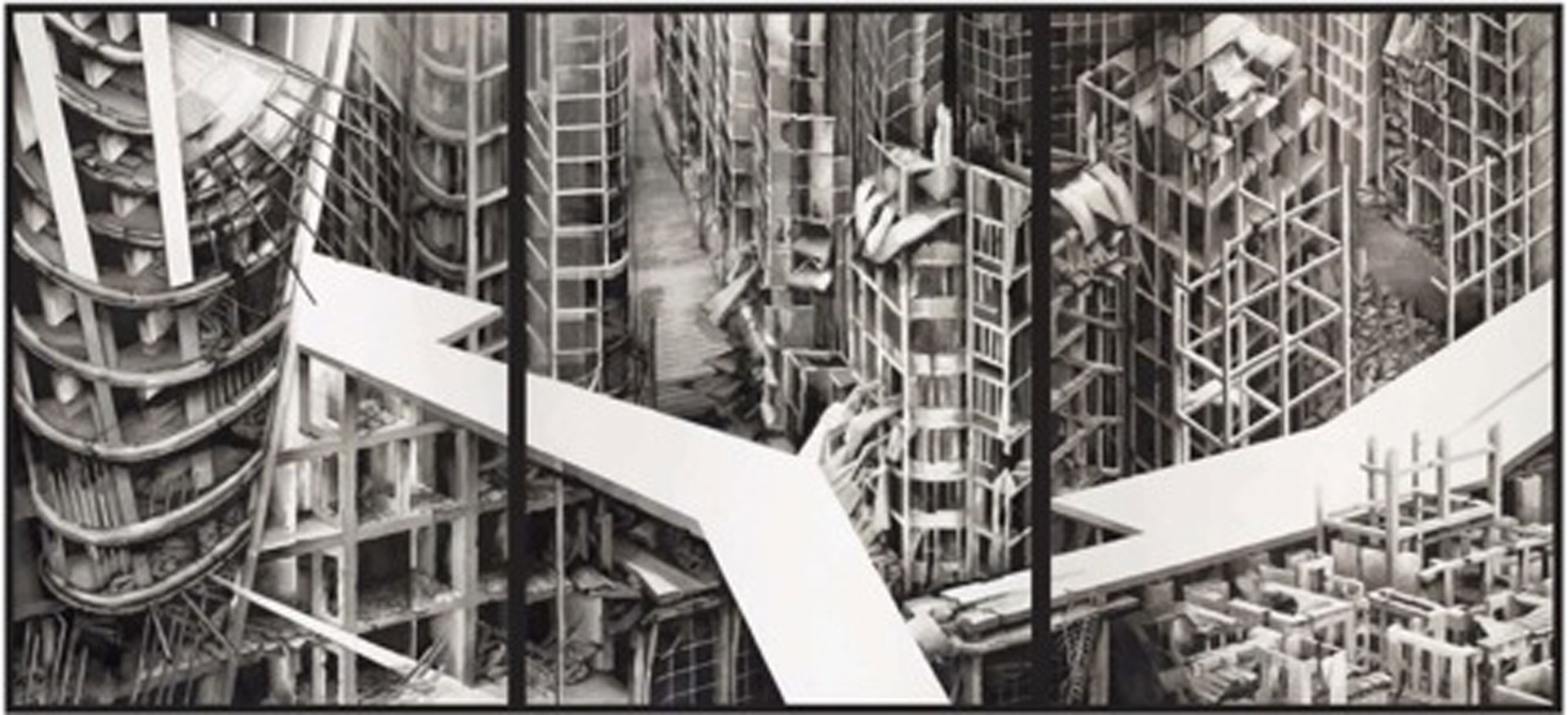

In 2019, as I visited the London art gallery Tate Britain, a large drawing attracted my attention. It was a black-and-white image of destroyed buildings and ruptured architecture, in a creatureless city empty of its people. As I moved closer to the drawing to look at its details, I felt a sense of connection, bending to see the title of the drawing: “The Destruction of the City of Homs,” by artist Deanna Petherbridge.

Melancholic, profound and powerful, the drawing took me back to the empty streets, another reminder of the people killed in the city, of the forcibly displaced people. It reminded me of my walk at the funeral of my friend in Baba Amr when he was killed in my street in 2011. It drew me in: I looked intensely at every single line, at every broken piece of stone. With the flood of images about the destruction of Syria’s built environment, I found in this drawing an homage to my city, a story told about Homs, here in my exile in London.

I immediately searched online for the artist. Born in 1939, Petherbridge spent eight months drawing Homs while in her late 70s. I felt touched and moved by the work and by Petherbridge, who felt the urgency and the moral responsibility to respond to the horrors of war by telling the story through her art. I immediately got in touch by email to begin a conversation that continues to date.

With nearly 7 million people displaced from Syria, a new Syria has been reconstructed outside its borders by exiles scattered around the world, through artistic and cultural efforts. From paintings, drawings and music to literature, films and theater, art has become a weapon to deal with the individual and collective trauma endured at the time of war.

Just like Picasso’s painting of the bombing of Guernica in 1937, which he painted from his exile in Paris, art and culture have remained at the forefront for diasporic Syrians to tell the world about their country: to keep their fight for peace, justice, freedom and equity going from outside Syria.

From her exile in Paris, Fadwa Souleimane, an actress and activist, continued to reconstruct hope at the darkest times, until her death in 2017 at age 47. Before leaving Syria, she faced the death sentence for her role in peaceful anti-government protests and was scorned by her own family. She found refuge in France in 2012 and kept hope central in her activism. “Even if they erase everything, we should not let them erase our dream,” she said in 2016. “If there is only one Syrian left, I am sure [s]he will build the Syria that we love. Syria is not a country, a geography. It’s an idea.”

Souleimane refused to surrender to the erasure of history. When the Syrian war had been turned faceless, and when the Syrian cause was turned from news headlines into a footnote in history, into a forgotten war, Souleimane continued to remind everyone about the role of art even at the time of crisis. She urged us to remember, not to forget. As she said in an interview in 2016: “The Syrian people have made the most beautiful revolution. … They made their revolution with art, dance and beauty and forgiveness. … These people should never forget the goal they went out for. We should never forget. We should never let the war destroy us from the inside.”

For over a decade now, the Syrian Revolution has led to an explosion of artistic and cultural efforts. Many well-established artists have continued their pre-2011 efforts while reflecting on the changing dynamics of war. Furthermore, the revolution has enabled the emergence of new artists who were oppressed or silenced before 2011, and it also laid the foundations for new themes to be explored.

Themes that deal with uprooting, estrangement, exile, home, displacement and nostalgia have been at the heart of many cultural projects. In her film “Dounia,” Marya Zarif, who grew up in Syria and now lives and works in Montreal, shows through animation the life of families in Aleppo and their search for a new home outside Syria as their city is targeted and destroyed. The film touches on some of the most pressing issues that oppress the minds of many refugees: Where is home? And what is home? Another film, “Peace by Chocolate,” traces the journey of a Syrian family who found refuge in Canada and stars Hatem Ali, an influential Syrian director who passed away at age 58 in Cairo in 2020.

As tangible and material cultural heritage sites have been deliberately destroyed, and as millions of people have been displaced from their country with only a few objects to remind them of home, many have turned to the intangible cultural heritage in their quest to belong.

Through such heritage, in the form of food, music and dance, a sense of refuge and home is rebuilt even as the tangible has been erased and millions are unable to return to their country, even its ruins.

Intangible heritage has created a sense of continuity to Syria’s rich culture. Throughout his scholarly work, Dr. Hassan Abbas produced significant writing on that heritage, including “The Cultural Map: A Tool for Development and Peacebuilding” and “Traditional Music in Syria.” In 2013, he warned of forgetting, of losing memories of those who lost their lives in the war, of the loss of “their names, their looks, their color, and their faces.”

And so he insisted on fighting to remember, saying that “they will never be forgotten as long as there are activists who document violations and stand as the guardians of memory.” In 2021, Ettijahat, a cultural organization founded at the end of 2011 to promote Syrian culture, released a series of videos entitled “Douroub” (Pathways), written and presented by Abbas. These 10 episodes explored different themes such as traditional crafts, children’s games, dance, music, rituals and social practices. He found in mapping culture a way to understand our past, especially when the past has been vanishing. “Social incubators of intangible heritage have been decimated,” he explained in this series. “Its inheritors are either being killed or forced to be scattered around the world. This poses a major threat to heritage if cultural institutions do not step up to protect and preserve it.”

Abbas died at the age of 66 in Dubai, UAE, while working on the final stages of “Douroub.” His legacy remains alive today.

Souleimane, Ali and Abbas pushed the boundaries to tell the story of Syria and Syrians through arts and culture. They found in art a tool to resist tyranny and destruction. Through their work, they built another Syria that makes us better understand who we are and what our past is. They invited us to preserve memory in the face of collective amnesia. Here I pay tribute to those who reminded us of the role of arts at the darkest moments, by writing about them and their work. We continue their douroub, their pathways.

In many news media articles and several academic circles, the story of Syria has often been told by non-Syrians. Many of us who have lived the horrors of wars and experienced the life of exile, forced displacement and trauma have felt that our story has been stolen from us by those who cared little about Syria and more about themselves. This is why many Syrians felt the need to construct and establish new projects, platforms and initiatives mainly led by Syrians, with their friends and allies.

This March will mark a decade since the launch of Al-Jumhuriya, which was founded by a group of Syrian writers and academics, both inside and outside the country. Al-Jumhuriya offers a platform for Syrians to speak in their own voice both from inside and outside the country, when many news media platforms have offered little or no space for Syrians to write.

I loved how Al-Jumhuriya brought to us in exile the voices of people we had not heard of before, especially those who wrote from inside Syria. For instance, it published 22 articles by Mona Rafea (which is a pseudonym), who writes from Homs. Rafea’s writing has offered a rare and critical voice that has reached out to the world to tell stories of those who have stayed in the city, providing a window into Syria. Rafea explores different themes such as loss, womanhood, masculinity, love and waiting. She paints vivid pictures of the fears, anxieties and dreams of the people of Homs. She describes the faces she sees as she walks the streets and imagines the worries and thoughts that occupy their minds. On the 10th anniversary of the Syrian Revolution in March 2021, she wrote “We Are Still Here,” a reminder that the people in Homs still exist, even when their stories and lives have disappeared from the public consciousness. “We’re still here, in Homs,” she writes. “There is still a firmness within us. We walk, and sleep, and eat, and fear, and dream. What matters is that we still dream. The one thing we are still certain of is that no one can uproot what is in our hearts, no matter how much the opposite may appear to be the case.”

Other emerging initiatives include events, such as the recently launched Syrian Arts and Culture Festival (SACF), the first London-based festival focused on Syria. But it was not the first in the U.K.

Since 2017, a group of Syrian men and women based in Manchester, all volunteers, have put together another festival called “Celebrating Syria.” Manchester is home to the second-largest Syrian community in the U.K., and the festival is organized under the umbrella of the Rethink Rebuild Society charity. This year, I joined the organizing team as a volunteer to put together the 2022 program.

For team member Hala Khdeer, “art and culture are tools of resistance.” She told me in an interview that “when I came to Manchester, I felt that this Syrian community has given me the space to continue my resistance.” For her, through this festival, the resistance can continue even from afar, collectively as well as on the personal level.

The festival offers an exciting platform to reach out to all the people in Manchester but also to connect to other Syrian cultural movements in the U.K., Syria and the rest of the world. The team is diverse, but what brings us all together is the desire to protect Syrian identity without being isolated from the society that welcomed us. We want to introduce this country where we live to our Syrian identity.

Petherbridge’s drawing of Homs has lived in my mind and heart since I saw it at Tate Britain. It is a powerful and monumental masterpiece that will remain a reminder of the horrors of war. It is an homage to the people whose lives have been reshaped by violence. While we hear often about political powers during war, we rarely hear about the effect of these wars on people’s homes and everyday life. This is why Petherbridge’s work felt like a shift in what observers see at the time of war, namely everyday life, including peoples’ homes. It is a symbolic work, “but it still demanded that I drew every inch of its surface with an immense attention to detail,” Petherbridge says, “as if, by so doing, I could commemorate all the imaginary people and their activities: the office buildings, the factories, the mosques, the schools and hospitals, the homes, apartments and workshops and their bombardment to rubble and dust.”

As we approach the 11th anniversary of the Syrian Revolution, it is time to acknowledge the incredible work done by Syrians to tell their stories through arts and culture. And it is also time to celebrate the wonderful stories told by many people who are not from Syria, like Petherbridge, who have kept our struggle and plight for justice, freedom and dignity alive. This beauty is shaped by the sense of solidarity that brought us as human beings closer to one another, that made us better understand the pain of other people. It is the empathy we share, the beauty of art, the love for peace, the search for a place to call home in this world.

So join us this year in celebrating Syria. Join us every year in the hope that one day we will be celebrating not only in Manchester but in Syria.