The first things visitors to our home would notice were the wayang puppets in our hallway and a bamboo angklung in the living room, a percussion instrument that my father used to shake. They weren’t typical Dutch decor; they were Indonesian. For years, I wondered why some of our family lived in Indonesia while we — my parents, grandparents and an aunt — were in the Netherlands, and why my surname didn’t match the rest of the family. The answer was not uncommon for children of refugees. “It’s complicated.”

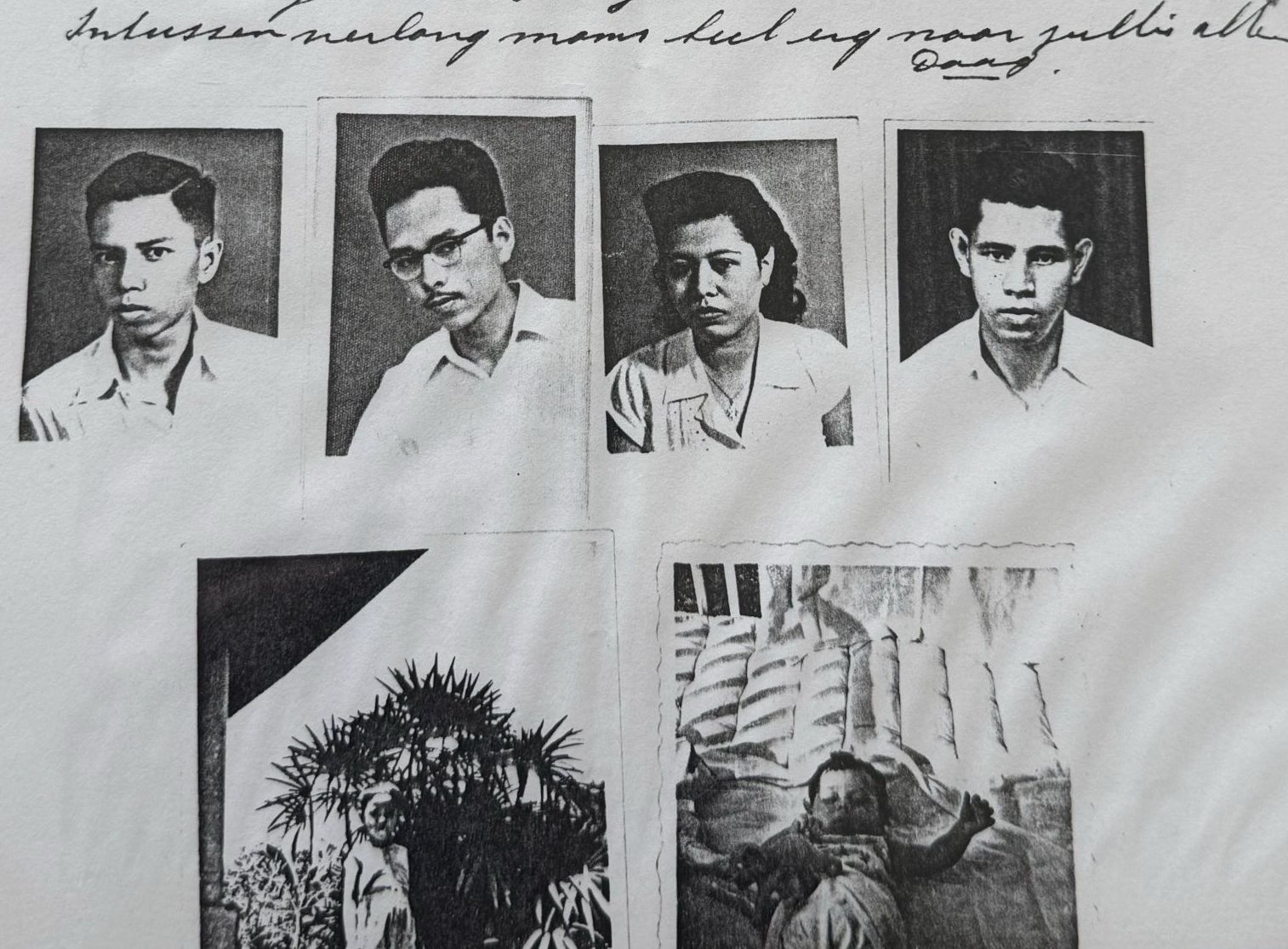

My father often phoned his brother Harry at dawn while letters from another brother, Frans, arrived and were read quietly. The story itself was behind glass. One framed letter from 1958 hung on our wall, and tucked beneath it were small portraits of my father and his siblings — Max, Frans, Harry (Henri) and Emma. “My dearly beloved children,” it begins, “Whatever may happen, you must always stay together, just as Mama keeps your photographs together and loves each one of you with distinction.” It was a plea to a scattered family.

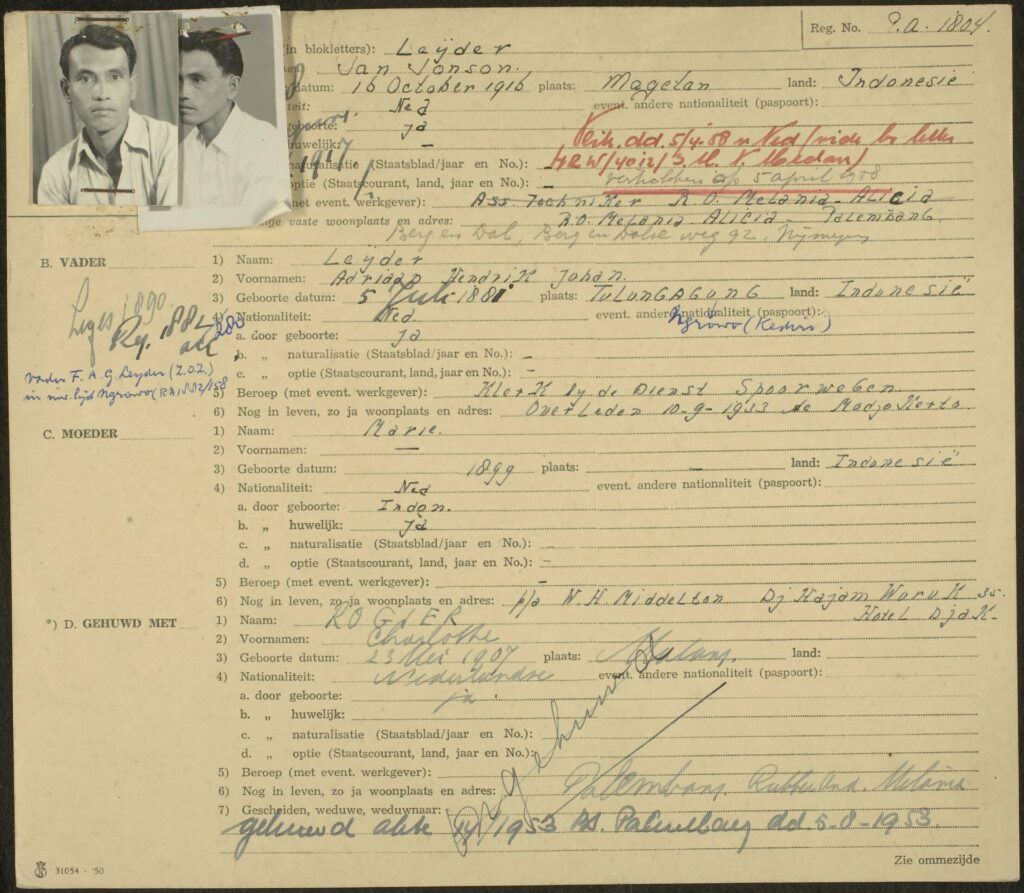

My surname comes from my paternal grandfather, a Royal Netherlands Navy sailor, whom my father never really knew. He and my grandmother, Charlotte, divorced in 1950. Captured by Japan during World War II, he was imprisoned in the Fukuoka 2B Camp and survived the atomic bombing in Nagasaki. After the war, he emigrated to the United States and started a new family. He died in 1987.

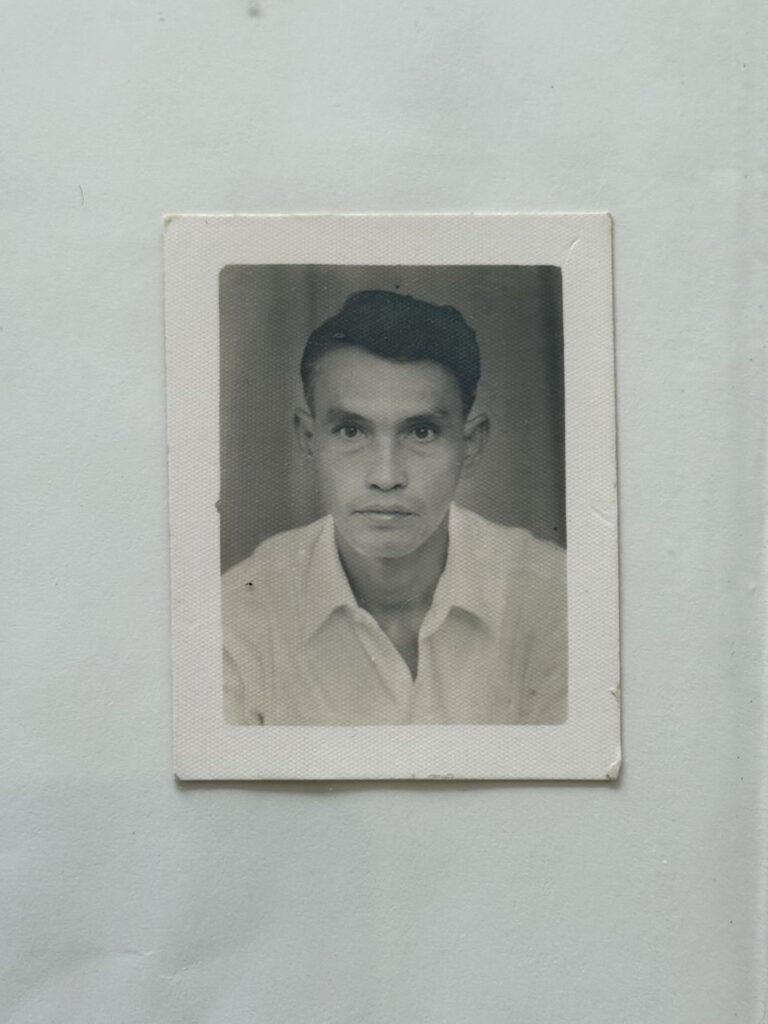

After he and my grandmother Charlotte divorced in the 1950s, there was no further contact. My father remembered him only as a blur, and we did not learn his whereabouts until much later. My father was raised by Jan Jonson Leijder, the man I knew as my grandfather. Many families were separated during and after the war, and ours was one of them.

When Jan died in 2004, I was 11. At his home in the eastern city of Nijmegen, I found a battered briefcase under a desk and insisted we take it with us. It remained unopened. Years later, after watching “Indo’s Silence” — a film about third-generation Dutch Indonesians breaking family silences — I opened it and found photographs, consular forms and letters, and inscribed in them was a history of falling empire, colonial decoupling and rising nationalism that would irrevocably mark those who lived through it.

The letters revealed what my family rarely said. Jan had also been a prisoner of war forced to work on the Burma Railway, which came to be known as the “Death Railway” after Japan’s invasion in 1942. His internment card shows he was captured on Java and shipped to a Thai prisoner-of-war camp. Like many Indo (mixed Dutch-Indonesian) men placed in the colonial European category, Jan had been conscripted into the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL), the colonial military force, with promises of pay, housing and training, which made the military a useful ladder in a racially stratified society. It also tied him to the collapse of an empire.

After Japan’s surrender in 1945, Indonesian nationalists led by Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta declared independence, and a revolution followed. The Dutch government tried to hold on to its possessions by launching a full-scale colonial war masked as “police actions.” Known as the Dutch East Indies, Indonesia was an important source of income for the Netherlands. It was especially reluctant to part with prizes like the plantations and oil in Palembang. The war was merciless, with many atrocities.

The new Indonesian Republic pursued decolonization in earnest. Daily life could be precarious for people seen as aligned with the Dutch — especially Indo-European families, Ambonese people (from the eastern archipelago of the Moluccas) who served in the colonial army, and in some instances Chinese Indonesians and the mostly Protestant Menadonese (native to North Sulawesi province). There was constant harassment and sporadic violence, notably during the 1945-46 Bersiap (also known as the Indonesian War of Independence) and again in 1957-58 when Sukarno’s government ordered the seizure of Dutch businesses, leading to the expulsion of many Dutch citizens, including Indos, and the subsequent formalization of the nationalization process. Others, including Sutan Sjahrir, a leading revolutionary who helped Sukarno during the independence war and later became the first prime minister of Indonesia, explicitly described Indos as “our own people” and urged fellow nationalists not to target them.

Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, officials began sorting would-be repatriates into “Western-oriented” and “Eastern-oriented” to determine who was assimilable, replicating the racist colonial policies of the Dutch East Indies.

In the briefcase I had recovered from Jan’s home, I found evidence of how this machinery impacted people’s lives. A 1953 marriage certificate shows Jan, then a technician at the Melania Alicia rubber estate in Palembang, marrying my grandmother Charlotte. A letter from N.V. Rotterdam-Tapanoeli Cultuur-Maatschappij, a rubber plantation company, confirms he paid his dues, and a consular certificate affirms his Dutch nationality. The same company forwarded a telegram from Batang Toru to my grandmother, who by then was staying at Pension “Beatrix,” a boarding house in the eastern village of Berg en Dal that was used by Dutch Indonesian arrivals. “The situation is becoming untenable,” it reads, “we will try to reach Medan together.” The likely recipient of the telegram was Jan, since an immigration paper from Medan on April 1, 1958, shows he was granted an exit and reentry permit.

When my father and I went through these papers, he recalled one of the few conversations he had with Jan about that period. Indonesia was facing internal strife as the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PRRI), a rival government set up in Sumatra, rose up against the central government in 1958, and Sukarno responded with force. Jan left the plantation for Medan in a convoy of vehicles painted with a red cross to avoid being shot at by either side.

A telegram given to Charlotte notes that Jan flew out on April 5, 1958, to the Netherlands. A follow-up letter from the plantation company, dated April 10, 1958, confirms his arrival and notes that he was staying at the same Pension Beatrix as my grandmother and father. A month later, as part of a response to communication by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Jan says that he cannot deliver any information on his youngest brother, D. Leijder. “According to stories that I’ve heard, he was killed in Tarakan during the Second World War.” Tarakan, located in northeastern Borneo, was a major oil center in the Dutch East Indies and a site of intense fighting before it was captured by Japan on Jan. 11, 1942.

Once my grandparents arrived in the Netherlands, they started trying to bring the rest of the family over. Charlotte’s three older children were still in Indonesia, and the longer they remained, the more precarious their lives became. She explains how my oldest uncle, Max, in his latest attempt to reach the Netherlands, left Java for Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) but was returned to Jakarta by the authorities and briefly detained. She asks forgiveness for any perceived wrongdoing by her sons and appeals for understanding of the dire conditions they were living in. Harry, married with one child, had been unemployed for more than a year, and the household survived only on small acts of kindness. He was turned away wherever he sought work and treated as if he were not a citizen. His wife and child dared not leave the house because of the harassment they faced for being perceived as not fully Indonesian.

Frans, unmarried, worked under intense pressure, and his health suffered. Medical staff eventually sent him home after he was attacked by colleagues who did not want to accept someone of mixed Dutch-Indonesian heritage. Charlotte stresses that anything could happen to her sons, and that she believes that a place in the Netherlands is their only hope for survival and dignity.

In another letter from the 1960s, written to a Dutch newspaper, she writes that “a son who always behaved honestly and decently was never accepted anywhere, while others with poorer conduct secured a brighter future thanks to their appearance or the intervention of officials.” She is speaking about Max, born under the Japanese occupation, who never enjoyed the rights she wished for him. In his attempts to reach the Netherlands, she says, he ran into trouble and was repeatedly harassed and attacked by people he was expected to respect, often Dutch-born officials. Life in Indonesia had become increasingly difficult for him and, as a concerned mother, she concluded there was no point in him remaining there any longer.

The echoes of these words reverberate into the present. Then, files weighed people with labels like “Western-oriented” or “assimilable,” while today’s immigrants face forms that speak of case prioritization, safe-country lists and processing queues. The vocabulary has changed, but the effect is similar. Human lives are reduced to categories, while mothers and sons ask for the same thing: a roof above their heads and the right to stay together as a family.

In response to one of Charlotte’s letters, Philip H.M. Werner, then secretary general at the Ministry of Social Affairs, wrote on July 10, 1958, with a classic bureaucratic deflection: Visas for non-Dutch nationals fell under the Ministry of Justice, her request had been forwarded there and his ministry could not influence a refusal. On April 28, 1960, Princess Wilhelmina’s private secretary, J. Geldens, replied that the princess had read Charlotte’s letters with interest and, although the matter was the government’s responsibility, she had asked the Ministry of Justice to inquire. The secretary then conveyed, with regret, that a renewed inquiry produced new facts to justify revising earlier decisions, so residence permits for her sons would still be refused. Charlotte’s appeals kept ending in rejection, even as some politicians, such as H.W. van Doorn of the Catholic People’s Party, urged her to keep supplying documentation. The Ministry of Justice continued to say her three sons were adults, not in mortal danger or serious difficulty, and therefore ineligible to come to the Netherlands.

The Werner Commission, established in 1952 by the Dutch government and chaired by the same Philip Werner, was tasked with advising the Dutch government on the “best future prospects” for repatriates. Rather than simply assessing practical needs, it entrenched a deeply racialized vision of belonging, sorting people as “Western-oriented” or “Eastern-oriented,” judging the capacity to adapt, and deciding who could enter the Netherlands on grounds of expediency.

By placing Dutch Indonesians on a spectrum from fully “Western” to fully “Eastern,” the commission effectively othered anyone deemed insufficiently European. It presumed those in the “Eastern” category lacked the capacity to assimilate and were inherently unsuitable for life in the Netherlands. In a textbook case of Orientalism, people were reduced to racialized policy objects rather than human beings.

Meanwhile, in Indonesia, the imperative to depart was becoming urgent. After independence, the Indo people had to choose a nationality. Those who kept Dutch citizenship were treated as foreign aliens (yet whose entry to the Netherlands remained less than certain). When the West New Guinea dispute flared in 1957, an anti-Dutch campaign swept the country, with Dutch companies seized, Dutch schools and meeting places closed, tens of thousands of Dutch passport holders expelled, and residence and work permits for anyone seen as “Belanda” (Dutch) withdrawn. Indos were treated as Dutch regardless of their papers. Those who had opted for Indonesian citizenship were not immune; they were suspected of divided loyalties, steered away from government posts and better jobs, and subjected to police checks and street intimidation. The letters in our family echo that climate: Max was described as stateless, arrested more than once, unable to work and afraid to appear in public. That was what created the determination behind my grandmother’s appeals to relocate her sons.

The administrative logic rhymes with parts of today’s migration debate, including rhetoric from figures such as Geert Wilders and Dilan Yeşilgöz (ironically, the former has roots in Indonesia himself, while the latter is of Turkish-Kurdish descent). Yeşilgöz leads the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), which has often governed in coalitions. Over the years, several of its leading lights have used the language of conditional belonging that echoes the old assimilability tests faced by families like mine. In a 2024 debate hosted by Cafe Europe, VVD politician Malik Azmani said: “The Netherlands must remain the Netherlands. We decide who we allow in, and they must learn our values. There are migrants who have been on benefits for generations, who were admitted through asylum, who do not participate in the labor market, who do not integrate.” In 2016, then-Prime Minister Mark Rutte told his party congress that the Netherlands should “never again fall back into the naivety of the multicultural society” of the 1980s and ’90s.

In a reversion to colonial tropes, conditions are once again being set on belonging. A 2024 report by the Central Bureau of Statistics in the Netherlands undercuts the right’s claim and finds that major second-generation groups are raising themselves up. They live in larger homes, have higher labor market participation, higher incomes and higher educational achievement than the previous generation, with gaps narrowing relative to the Dutch average. This contradicts the picture of “migrants on benefits for generations” that politicians like Azmani have tried to paint. It shows upward mobility, alongside specific, group-bound challenges among some first-generation refugees that are real but not universal or hereditary.

Yeşilgöz also warned of an endless chain of family reunification, suggesting thousands of arrivals. But the immigration service’s analysis revealed at most dozens, forcing a rare admission of error from Yeşilgöz. Such attempts at stigmatizing family unity as something sinister also have their antecedents in the 1950s. Just as Werner’s categories and bureaucracy helped keep my grandmother’s children apart, today myths about “chain” reunification risk doing the same to other families.

It has been eight decades since Indonesia’s independence, and Dutch colonial history receives far more attention than before. Commemoration mostly focuses on violence during the colonial war. But colonialism also leaves a legacy that is less spectacular, and wounds that are longer lasting. Less attention is paid to how racist colonial policies were inherited and recycled, and how they still surface, in different forms, in European politics. I saw their ghosts at home in the way my father sometimes cried in his sleep, a trauma for which he never sought help.

That Wilders, who was convicted in Dutch courts for racial incitement, continues to publish dehumanizing imagery without impediment to his political career suggests that the Netherlands has yet to come to terms with its racist colonial legacies. Othering still pays political dividends. Commemoration once a year means little if the next day we slip back into the same patterns.

But it is not only the Netherlands that this legacy of othering has disfigured. In late December 2023, students from various groups started ambushing refugee shelters in Banda Aceh in Indonesia, demanding the deportation of the Rohingya refugees housed there. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees said these were the consequences of a coordinated disinformation campaign with the aim of inciting hatred against refugees. This prompted the Palestinian journalist Hebh Jamal to criticize Indonesia for its hypocrisy in claiming support for Palestinian independence while treating Rohingya refugees as subhuman. Nor can one forget Indonesia’s racism against Indigenous Papuans, and the repression that, according to Human Rights Watch, includes extrajudicial killings, detention, torture and mass displacement.

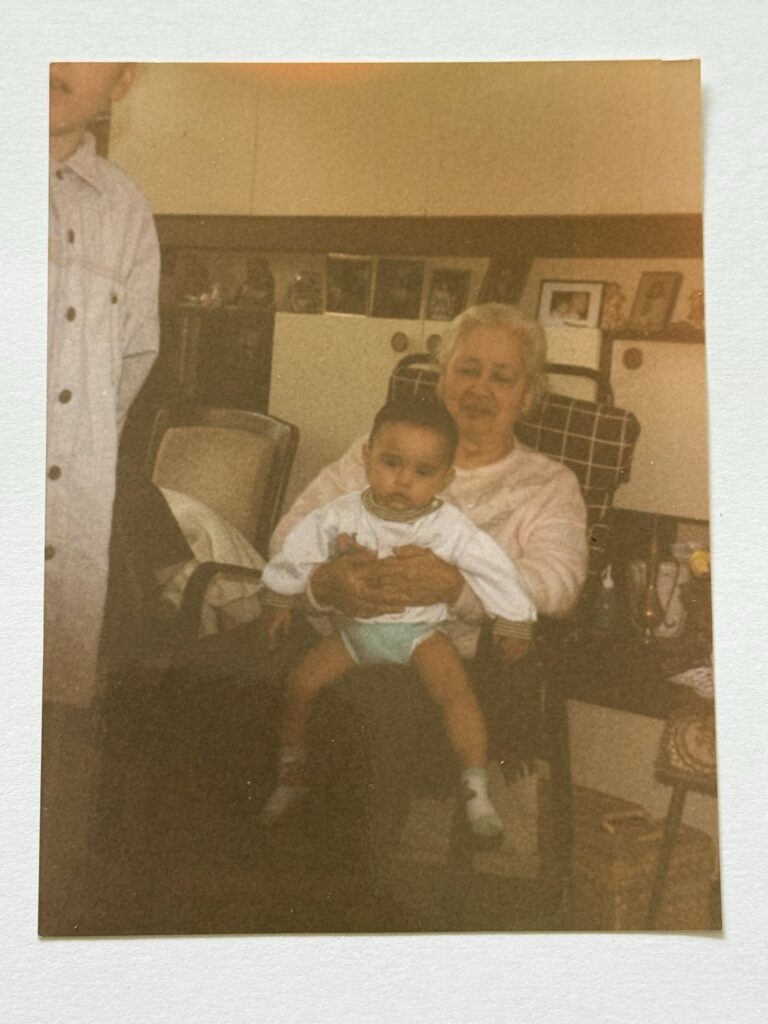

My father is the only one of his family still alive. His sister, who lived in the same country as us, and his brothers, who remained in Indonesia, have all passed away. It was hard for him to say goodbye, but technology helped. I remember setting up a Skype call with my cousins so he could say farewell to his brother Harry, as he hugged me with tears in his eyes. From time to time, someone adds me on Facebook who turns out to be a relative in Indonesia. It reminds me how large our family is there and how small it is here. One day, I may be among the few left, once my father’s time also comes.

The feeling of in-betweenness is very present in who I am. Culturally, I am Indonesian. I like to cook and enjoy an authentic dish such as the spicy mackerel of “ikan pepesan,” and I will happily smear sambal on a peanut butter sandwich. My taste in music is open-minded: I might be at a techno festival and then listen to blues, soul and jazz at home. I rarely make appointments with friends; I drop by and see if someone is home, without expectation. My door is always open for those whom I hold dear.

But at work, I am Dutch: results-driven, disciplined and clear in my communication, with a low-context, solution-oriented style. The bicycle is my vehicle of choice, and I do believe our infrastructure is better than that of many countries. We are social, and on sunny days the terrace is the place to be, sharing a beer with friends and eating bitterballen, a typical Dutch snack.

My grandmother’s plea was not answered as it should have been. None of us stayed together as she asked. So long as people are not treated with dignity and equality, the revolution that binds Indonesia and the Netherlands and, for me, the wider world, remains unfinished. To cite Sutan Sjahrir, the revolutionary who rejected violence, resisted populism and embraced a nationalism grounded in universal humanism: “We hate imperialism, not individuals. We fight oppression, not men. And in our freedom, there must be no room for hate.”

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.