Devlet Bahceli, the leader of Turkey’s Nationalist Movement Party and a partner in the country’s ruling coalition, surprised many when he recently called on the imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Abdullah Ocalan, to come to the Turkish Parliament and encourage his supporters to lay down their arms. Bahceli is a hardliner on the Kurdish issue but his reconciliatory gesture is not without precedent. One may doubt the sincerity of his words but they draw on a thousand years of history, and this history may help to rectify the mistakes of a century of strife. That Turks and Kurds could wake up one day to find themselves living peaceably in a common homeland is not beyond the realm of possibility — and such a reconciliation has been foreshadowed by some recent events.

During Turkey’s 2004 municipal elections, followers of the Naqshbandi Sufi order in the Kurdish city of Bingol in the southeast of the country gathered in a public square and chanted: “Idris Bitlisi is here, so where is Yavuz Selim?” The slogan dates back centuries and invokes historic Turkish-Kurdish ties. Sheikh Idris Bitlisi, a Kurdish religious scholar, administrator and statesman, and a key figure in this history, forged an alliance with the Ottoman Sultan Selim I, known as “Yavuz” (the Grim), during the Ottoman expansion into Arab lands in the early 16th century. From the Battle of Marj Dabiq in Aleppo (1516) to Raydaniyah in Egypt (1517), Selim’s Arab campaigns relied on Kurdish support. In 1515, one year after an Ottoman victory at the Battle of Chaldiran, Shah Ismail, the founder of Safavid Iran, responded with an attack on Amed (modern-day Diyarbakir). But this retaliation ultimately failed when 40,000 warriors, led by Bitlisi, came to the Kurds’ aid, breaking the Safavid siege on Diyarbakir and rescuing its new Ottoman ruler, Beqali Muhammad Pasha. Upon reaching the city’s gates, Bitlisi famously declared, “Idris Bitlisi is here, so where is Yavuz Selim?”

The chant went largely unnoticed in Turkish media. But after being adopted by a Kurdish Naqshbandi group loyal to the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), it did catch the attention of Ocalan. He mentioned the phrase in meetings with his lawyer and referenced it in his prison memoir, “Defending a People.” He was surprised at its naivety, given the political climate at the time. The Turkish government’s agenda back then did not include a political solution to the Kurdish issue. Nonetheless, those chanting appeared to be seeking a new Turkish leader, akin to Selim, to revive the alliance. Their hopes were pinned on the prime minister at the time, the current President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who had recently announced a policy of “openness” toward Kurds.

Far later in history, Kurds took on a similar role to that of the early 16th century, as shown by 19th-century accounts from the Najd region and the Arabian Peninsula during the rise of the first Saudi state. Both “The Title of Glory in the History of Najd” by Abdullah bin Bishr and “The History of Najd” by Hussein bin Ghannam, which chronicle the history of the puritanical Wahhabi movement, mention the Kurds in the context of an Ottoman governor of Baghdad preparing a Kurdish army to fight the Wahhabis. In the last century of Ottoman rule, the Naqshbandi order in Kurdistan was instrumental in defending the Ottoman state’s Sufi identity against the growing Wahhabi calls for a fundamentalist doctrine.

The shared history between the Kurdish and Turkish peoples therefore spans centuries, but it has been overshadowed by political turmoil and the collapse of relations in the century since the founding of the Turkish nation-state. This collapse not only redefined this relationship but also led to the rewriting of history.

A few years after the end of World War I in 1918, as new nations and borders emerged in the Middle East, the region’s collective memory began to shift. The fall of the Ottoman Empire forced its former subjects to reexamine their ties to the defunct imperial power. The Kurds took part in this effort to craft a new historical memory, particularly in response to the new Turkish Republic’s denial of Kurdish identity.

Kurdistan was an officially recognized geographical region during the Ottoman era, known as the “Kurdistan Eyalet.” Though it later fragmented into smaller administrative divisions, such as the provinces of Diyarbakir, Mosul and Van, these regions were still referred to as Kurdistan in Ottoman records. Ottoman rule over Kurdistan lasted four centuries, a period characterized by long stretches of mutual agreement, punctuated by periods of conflict and rebellion.

In the early years of the Turkish Republic, the Kurds adopted the Arab narrative of “Ottoman colonialism.” This narrative about the imposition of Ottoman rule had paved the way for the Arabs to work toward independence and establish self-governance. It was ingrained in the education systems of the newly independent Arab states. The anti-Ottoman sentiments spread with ease because the final two decades of the Ottoman Empire were marked by bloody factionalism and conflicts under the rule of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). Established in 1889 as the “Ottoman Union,” the CUP had adopted Turkish nationalism after coming to power in 1908 — a move that contributed to the empire’s disintegration. The destructive legacy of the CUP still looms large in Kurdish national memory.

Turkish-Kurdish relations were built on formal alliances rather than conquest, resembling a partnership rather than subjugation, but the CUP, and later the Turkish state, denied this shared history, which shocked the Kurds. As Turkey transformed into a nation-state with a singular identity — one language, one people and one history — Kurds were recast as Turks who had simply lost their language. Kurdish political sentiments were shaped by feelings of betrayal well into the 20th century.

The Turks first encountered Kurds in 1042, when a few thousand Turkish soldiers marched to Mayyafariqin, the capital of the Kurdish Marwanid Emirate near Diyarbakir, demanding allegiance to their new ruler, Sultan Tughrul Bey of the Seljuks. Two of Tughrul’s commanders besieged the Kurdish capital, which was under Prince Nasr al-Dawla bin Marwan’s rule. But both were killed in an internal quarrel, meaning the Kurds escaped subjugation — for the moment.

The second major encounter occurred in 1058, when Arslan al-Basasiri, the head of the Turkish military in Baghdad, overthrew the Abbasid Caliph al-Qaim bi-Amr Allah and pledged allegiance to the rival Fatimid Caliph al-Mustansir Billah, who ruled from Cairo. This rebellion nearly ended the Abbasid Caliphate but the disaster was averted by a seven-year drought in Egypt, which depleted the Fatimids’ military strength. At the time, three main powers remained in the east: the Uqaylid Emirate, which ruled Mosul, western Iraq and Aleppo from 990 to 1096; the Kurdish Marwanid Emirate, which ruled Kurdish territory and parts of Armenia for almost as long as the Uqaylids; and the Seljuks, a mobile force with an ambiguous identity, ethnically Turkish but culturally and linguistically Persian, lacking a permanent homeland but with military bases in Rayy, Isfahan and Baghdad.

The Uqaylids, Marwanids and Seljuks each contributed to protecting the Abbasids when they were on the verge of collapse. The Uqaylids safeguarded the deposed Abbasid Caliph al-Qaim bi-Amr Allah, relocating him to Ana in western Iraq after he was overthrown by al-Basasiri. Despite their Shiite leanings and doctrinal closeness to the Fatimids, the Uqaylids were loyal to the Abbasid caliph. The caliph’s wife and son found refuge with the Kurdish Marwanids in Mayyafariqin. But in spite of their enduring loyalty, neither Uqaylids nor Marwanids took military action to restore the caliph to the throne. This inaction allowed the Seljuks to expand unopposed into Arab lands. The Seljuk leader Tughrul succeeded in killing the usurper al-Basasiri after battles in Iraq, and thus also appropriated the role of protector of the Abbasid family from the Arabs and Kurds. The caliphs became figureheads whose authority was solely religious, and the era of Seljuk dominance had begun.

By 1096, the emirates of both the Uqaylids and the Marwanids had fallen to the Seljuks. By 1100, Arab influence in the Islamic world had been reduced to the Abbasid caliph’s palace, the Shiite Fatimid state in Egypt, the Hijaz in modern-day Saudi Arabia, and Morocco.

The Seljuks gradually shifted their power base from Iran to northern Mesopotamia and the Levant, though they did not establish a lasting presence in Kurdish territories. Arabs faced successive defeats and their rule over lands they had controlled since the early Islamic conquests gradually disappeared. The Kurds were similarly impacted, though the Seljuks relied on Kurdish territories and warriors to support their battles against Byzantium. The Marwanid state, which had spearheaded the Islamic expansion against Armenia and Byzantium, became critical to these efforts.

All of this became significant during the Battle of Manzikert on Aug. 26, 1071, at which the Seljuks defeated the Byzantine army and established control over Anatolia. Sultan Alp Arslan, Tughril’s nephew, commanded only about 4,000 soldiers while, according to the historian Sibt ibn al-Jawzi (1186-1256), the Kurds contributed 10,000 horsemen. This division of forces is further corroborated by the Byzantine historian Michael Psellos, who was present at the battle. Psellos admired the sultan’s army and referred to Alp Arslan as the “Sultan of the Kurds and Persians.”

Having contributed more knights to the battle, the Kurds received an equal share of the spoils of war. Ibn al-Azraq, the historian of the Marwanid state, mentions the distribution of war spoils among the inhabitants of the Marwanid provinces near the battlefield. The Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk visited the Kurdish Prince Nizam al-Din Nasr bin Ahmed’s palace and, as a reward for support in the battle, granted him the title “Sultan of Princes,” positioning him second only to Alp Arslan among the rulers of provinces loyal to the Abbasid Caliphate.

However, the shared sacrifices did not translate into an enduring political friendship. The Seljuks pursued alliances only sporadically, even with the Abbasid caliph. Sultan Malikshah, Alp Arslan’s successor, nearly expelled the caliph from Baghdad before the former’s sudden death in 1092. The Marwanid-Seljuk collaboration at Manzikert that reshaped the history of the eastern Mediterranean received relatively scant attention in historical writings.

The different characteristics of the Kurdish and Seljuk ruling classes shaped their subsequent relationship. The Kurdish entity was settled, with a stable population base, while the Seljuks were nomadic. The Kurdish ruling class did not seek to expand beyond Kurdish territories and, unlike the Islamic border emirates, the Marwanid state was not a military opponent of Byzantium. Instead, it functioned as a buffer between Islam and Christianity by maintaining positive relations with the Eastern Roman Empire, to the benefit of the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. The Marwanid Emirate maintained a close relationship with the Byzantine Empire, particularly during Prince Nasr al-Dawla bin Marwan’s 50-year rule. Before Nasr, the Byzantine Emperor Basil II had struck a deal with the Kurdish ruler Muhdhid al-Dawla al-Marwani, granting him the unique titles of “Maxitrus” and “Duke of the East” — an honor never before conferred on a Muslim ruler.

Meanwhile, the Seljuks were driven by a need to find new lands for settlement and conquest. Their expansionist tendencies led them into conflict with both Christian and Islamic powers. They even relieved their former Kurdish allies of their role as a buffer between the Muslim world and Byzantium.

According to Turkish historians, the Turkish-Kurdish rout of the Byzantine army opened a corridor for the Seljuks to move westward. Yilmaz Oztuna, in his “Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire,” notes that after the Battle of Manzikert, Sultan Malikshah captured Antioch from the Byzantines in 1084. Following this, “hundreds of thousands of Turks came from the east and settled in Anatolia, starting with the cities.” The Seljuks passed through Kurdistan on their way to Anatolia rather than settling in Kurdish lands, despite facing no significant opposition. To avoid losing their lands to the intransigent Seljuks, the Marwanids facilitated their safe passage to the zone of conflict along the Byzantine frontier.

Today’s PKK leader Ocalan bases his history of Turkish-Kurdish consensus on this cooperation, arguing that major victories were shared between the two groups for a thousand years, until the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923. However, despite Turkey’s annual celebration of the Battle of Manzikert, Erdogan is yet to acknowledge Kurdish participation in this victory. His “Turkey 2071” program commemorates the millennium anniversary of the battle but Kurds are excluded from such remembrances.

The Kurdish role in the Turkification of Anatolia came at a steep cost: They had to sacrifice sovereignty for survival. The Turks kept the Kurdish rulers but brought their territories under Turkish administration. A Kurdish-Arab uprising against Seljuk rule failed, despite the assassination of Nizam al-Mulk and the death of Sultan Malikshah.

And so the Kurds found themselves playing a subordinate role in their own lands. Despite intermittent conflicts between Kurdish and Turkish rulers during this era, the Marwanids avoided direct confrontation with the Turks and Turkish princes came to dominate the Levant, Iraq, Anatolia and Kurdish territories.

A century after the Seljuks arrived in Abbasid lands, their empire began to fragment, as their mobile power receded, becoming confined to Anatolia. Various Turkish leaders who had served the Seljuks rose to power, including the Artuqids in Kurdish lands and the Zengids in Mosul and Aleppo. Amid internal Turkish conflicts, the Zengids turned to the Kurdish military class for support, notably the Ayyubid family. Since Mosul bordered a large Kurdish population, Kurdish involvement was crucial in mitigating local conflicts.

The two dynasties fell out, particularly when the Kurdish leader Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi (aka “Saladin”) came to prominence. Saladin’s rise helped counter the Crusaders and halted their advances along the Levantine and Egyptian coasts, but he first had to eliminate the Fatimids in Egypt. The rise of sectarianism spurred by the Shiite Fatimid state in Egypt had complicated matters. Sunni jurists and Seljuk-Zengid historians came to frame later military expansion as part of a broader struggle against Arab “esoteric groups.”

The Ayyubids sought to redress the imbalance of the settlement between the Marwanids and Seljuks. Contemporary sources such as Ibn al-Athir’s “Complete History” and Ibn Shaddad’s “Items of Great Importance Regarding the Princes of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia” describe bloody confrontations between the Ayyubids and the ruling Turks, resembling intermittent civil wars. Eventually, the Ayyubids prevailed, and made use of subordinate Turkish leaders for governance and administration during 80 years of Ayyubid rule.

Turkish-Kurdish tensions persisted until around 1200, partly due to the Turks’ failure to consolidate their conquests politically. The Seljuks of Rum in Anatolia launched repeated campaigns against Byzantium, while Saladin forged alliances with Constantinople against the Catholic Crusaders. Byzantine animosity toward Western Christian dominance had peaked in 1182 with the “Latin Massacre,” in which Byzantines attacked Italian trading settlements and killed thousands of Catholics. The Latins retaliated by capturing the Byzantine city of Thessaloniki. Saladin took advantage of the rift, forming links with the Byzantine Emperor Isaac II and recruiting elite Kurdish tribal fighters from the mountains of Kurdistan to serve in the plains of Egypt and the Levant. Byzantium welcomed the alliance with Saladin because it was on the verge of losing its commercial ports because of a harsh European blockade and constant Seljuk attacks. In the Byzantine emperor’s first letter to Saladin, he addressed the sultan amiably as “my brother, the Sultan of Egypt, Saladin.”

The Turks had transformed Anatolia into a realm of nomadic armies, causing instability. Turkish tribes, particularly the Turkmen, refrained from settling in cities for much of this era, a pattern that persisted during the time of the Aq Qoyunlu (“White Sheep”) state in Diyarbakir. This Turkmen tribe ruled Kurdistan and Iraq for several decades, yet they did not establish cities for their Turkmen subjects. After their defeat at the hands of the Ottomans, the Aq Qoyunlu withdrew. Unlike the Qara Qoyunlu (“Black Sheep”) — an Alawite Turkmen tribe that ruled Iran and Kurdistan and helped found the Safavid state — the Aq Qoyunlu did not leave a legacy. Bitlisi, the Kurdish administrator who later allied with Sultan Selim I, served in the court of Uzun Hasan, the most famous ruler of the Aq Qoyunlu. Under the nominal control of this Turkmen dynasty, powerful Kurdish principalities flourished, including in Bitlis, Hakkari and Bahdinan. However, the Turkish presence did not lead to significant social settlement in Kurdish cities.

Saladin and his Ayyubid successors suppressed internal tensions by directing their military focus toward the Crusaders rather than warring with the Turks. By the Mamluk era (1250-1517), the power of the Seljuks in Anatolia had diminished and the region fragmented into various Turkish emirates, including the emerging Ottoman Emirate. The Kurdish region also became a collection of small neighboring emirates, most notably the Emirate of Bitlis. Civil conflicts between these Kurdish emirates were relatively mild. The Euphrates formed the dividing line between Turkish and Kurdish territories, with Kurds to its east and Turks to the west, though there were areas in the west with significant Kurdish populations, such as Adiyaman, Gaziantep and Maras.

The influence of Asian powers on the eastern Mediterranean persisted, beginning with Genghis Khan’s military campaigns directed toward the Islamic centers of power and continuing through the campaigns of Timur (aka Tamerlane). Timur’s influence peaked with raids on various kingdoms in the eastern Mediterranean, culminating in the Battle of Ankara on July 22, 1402, at which he defeated the Ottomans and captured Sultan Bayezid I. It was the largest battle of the Middle Ages in terms of the size of the armies and its impact. According to Yilmaz Oztuna, the combined armies totaled around 300,000 soldiers. Timur next took Bursa, the most prosperous Ottoman commercial city in Asia Minor, razing it to the ground.

The Kurds’ strategic importance became clear when the Turkmen Aq Qoyunlu emirate in Diyarbakir formed a trade alliance with the Italian Duchy of Venice, aiming to undermine the Ottomans after they captured Constantinople in 1453. In response, the Ottomans swiftly eliminated the Aq Qoyunlu emirate, enabling the Kurds to regain sovereignty over their regions — although the Alawite Turkmen in the Safavid state still posed a threat to the Ottomans.

Waning Mongol power in the eastern Mediterranean set the stage for domination by three major players: the Safavids, Mamluks and Ottomans. The Safavids took control of the Iranian plateau and Azerbaijan, gaining support from the Alawite Qizilbash, a mobile Turkmen force. They imposed their authority over the Persians through oppression and violence, converting the Iranian plateau to Twelver Shiism. The Mamluks secured control from Aleppo to Cairo and the Hijaz, and their sultans assumed the title of “Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques.” The Ottomans dominated Anatolia, the northern Levant and Kurdistan, backed by the Kurds. This ancient tripartite balance — represented today by Iran, Egypt and Turkey — has persisted into the present.

The Ottomans were compelled to ally with the Kurds because the Safavids had turned the Turkish tribes, especially the Alawite Turkmen, into a threat to Ottoman stability. Although the religious and sectarian identity of the Kurds was somewhat ambiguous, notable Sunni Kurdish scholars aligned with the Ottoman state. Sheikh al-Islam Abu al-Saud (d. 1574), a Kurd from Amadiyah (present-day Iraqi Kurdistan), issued fatwas in service to the Ottoman sultans, which justified the killing of the Turkmen leader of the Bektashi Sufi order, Hamza Bali, along with his disciples, and permitted the sultans to execute their own sons and brothers. This Kurdish jurisprudential support was significant given Arab Sunni jurists’ reluctance to fully recognize Ottoman authority. This strategic alliance with the Kurds and their shared Sunni identity helped the Ottomans dominate the region and counterbalance both Safavid and Mamluk influence. Meanwhile, the Safavid state in Persia was arming itself with Shiite jurists from Jabal Amel (in modern-day southern Lebanon) and Bahrain, while the Mamluks relied on the legitimacy of the Abbasid caliph, though his authority was largely ceremonial and confined to the walls of his palace.

The emergence of the Safavid dynasty in 1501 alarmed the Ottomans. The Safavids were Kurdish in origin, Turkmen in military composition, Shiite in doctrine and Persian in culture. Their Kurdish roots traced back to Prince Firuz Shah Zarin of Sinjar, but the Turkmen predominance in the army did not translate into any meaningful Kurdish or Turkmen influence. Instead, the Safavid state emphasized Persian cultural revival with a strong Shiite religious foundation.

As the Safavids expanded westward toward the Euphrates, they brought all of Kurdistan under their rule before clashing with the Ottomans. This Safavid-Kurdish alliance was initially beneficial for the Kurds, as Bitlisi, who played a central role in the alliance, helped weaken the Turkmen Aq Qoyunlu tribe, which had previously dominated Kurdistan. In return, Shah Ismail Safavi refrained from imposing Shiism on the Sunni Kurds, making them an exception to the often violent enforcement of Shiite doctrine in Persia and Azerbaijan. In Iraq, Shiism spread primarily through proselytization.

The alliance with the Safavids brought significant economic benefits to the Kurdish emirates by freeing them from the obligation to pay taxes and fees to the Turkmen Aq Qoyunlu dynasty that had ruled Diyarbakir. But the relationship did not last. Bitlisi eventually ended his service at the Safavid court, publicly renounced Shiite Sufism (specifically the Nurbakhshia order) and aligned himself with the Ottoman Sultan Selim, both politically and religiously, embracing the Shafii Sunni school of thought.

The Chaldiran War of 1514 between the Ottomans and the Safavids provided an opportunity for the Ottomans under Sultan Selim I to both strengthen their alliance with the Kurds and weaken the influence of the Turkmen tribes, who had long resisted the Ottomans. Before the decisive battle, which crushed Safavid ambitions of making the Euphrates the western border of their empire, Bitlisi was tasked by Selim with organizing the Kurdish situation.

Bitlisi successfully unified the Kurdish emirates and convinced their leaders to adopt a special administrative system that preserved their hereditary rule. He also formalized the relationship between the Kurdish emirates and the Ottoman sultanate through a written agreement of self-rule, encompassing more than 46 Kurdish princes. In recognition of this Kurdish loyalty, Selim sent the Kurdish princes 15 banners and 500 royal robes as tokens of appreciation. Writing in the mid-17th century, the Ottoman traveler Evliya Celebi noted: “Since the law of Sultan Selim, these 12 governments have been ruled by hereditary princes. The ministers, by the order of the sultan, approve the transfer of rule within the lineage of the princes and the people of these states refer to their rulers as Khan.”

The Ottoman-Kurdish alliance beginning in 1514 was pivotal in transforming the Ottoman state from a semi-Balkan, semi-Anatolian entity into an empire. The Kurdish princes were granted the right to rule their emirates, pass on their power hereditarily and establish autonomous governments within Kurdistan. This autonomy helped solidify Ottoman control over the region and weakened the Safavids after Chaldiran. The Kurds became a buffer against Safavid influence and provided stability in the region. In return, they were rewarded with self-rule and prestige.

Although the Kurdish-Turkish agreement brought relative peace, it was occasionally violated. Between 1514 and the end of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent’s reign in 1566, the Kurds experienced some sanctions from the Ottoman Empire. A significant instance occurred when Suleiman removed a Kurdish prince from Bitlis and replaced him with someone outside the hereditary line. When Sultan Murad III came to power in 1574, relations further unraveled. Kurdish lands became frequent targets of Safavid raids, as Kurdistan found itself in the crossfire of the ongoing wars between the Ottomans and the Safavids. The military campaigns caused immense suffering, preventing any real development or prosperity in the region.

The Ottoman state left the defense of Kurdish lands to Kurdish princes. The sultanate intervened only when it deemed it necessary, forcing Kurdish leaders to pay the price for their nominal independence. The Kurds faced a Safavid military that outnumbered them in resources, leaving them vulnerable and isolated.

The Ottoman-Kurdish peace agreement placed strict limits on the growth of any central Kurdish authority that could unify or lead the Kurdish emirates in defense and administration. Kurdish leaders rejected the idea of electing a single leader, instead preferring Sultan Selim to appoint a prince over them, keeping their governance decentralized and dependent on the Ottomans.

Unlike the Persians and Turks, who incorporated trade into their political and imperial strategies, Kurdish leaders also largely neglected the commercial dimension, hindering their ability to build a centralized, imperial state. Like the Uzbeks, Baloch and Pashtuns, the Kurds seemed like a force resisting the expansion of commercial capital rather than engaging with it. As a result, the Kurds did not present themselves as attractive trading partners to imperial and later capitalist powers. Even in the agreements between Selim and the Kurdish princes from 1514 to 1516, the partnership was based on granting the Kurds freedom but keeping them politically isolated, without integrating them into the broader commercial and imperial networks of the Ottoman Empire.

The Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 has often been compared to the 1071 Battle of Manzikert in terms of the strategic alliances involved. It has been suggested that whoever allied with the Kurds at the battle would go on to achieve dominance across the region. Yet despite the potential for a lasting alliance of equals that might shape a new state with a dual character, over time, the strategic partnership between the Ottomans and Kurdish princes frayed.

As the Ottoman Empire’s borders shrank in the Balkans, it grew increasingly authoritarian at home. Its new vision included the abolition of autonomous emirates across the empire, including Kurdish ones. One by one, they fell. By 1834, the Ottoman Empire had dismantled the Emirate of Soran, located in what is now the Kurdistan region of Iraq. In 1847, the Emirate of Botan was eliminated, then that of Baban in Sulaymaniyah followed suit. These changes escalated religious and sectarian tensions, particularly between Kurds and Armenians. In the eyes of Kurdish princes and sheikhs, the Ottoman state appeared to favor Christians after the sweeping Tanzimat reforms of 1839 and the Islahat Fermani or Imperial Reform Edict of 1856 that promised greater religious equality. These changes alienated Kurdish leaders. By the time Sultan Abdul Hamid II ascended to power in 1876, the historical Kurdish emirates, which had existed since the early Islamic era, were gone, leaving behind chaos, massacres and mass displacement.

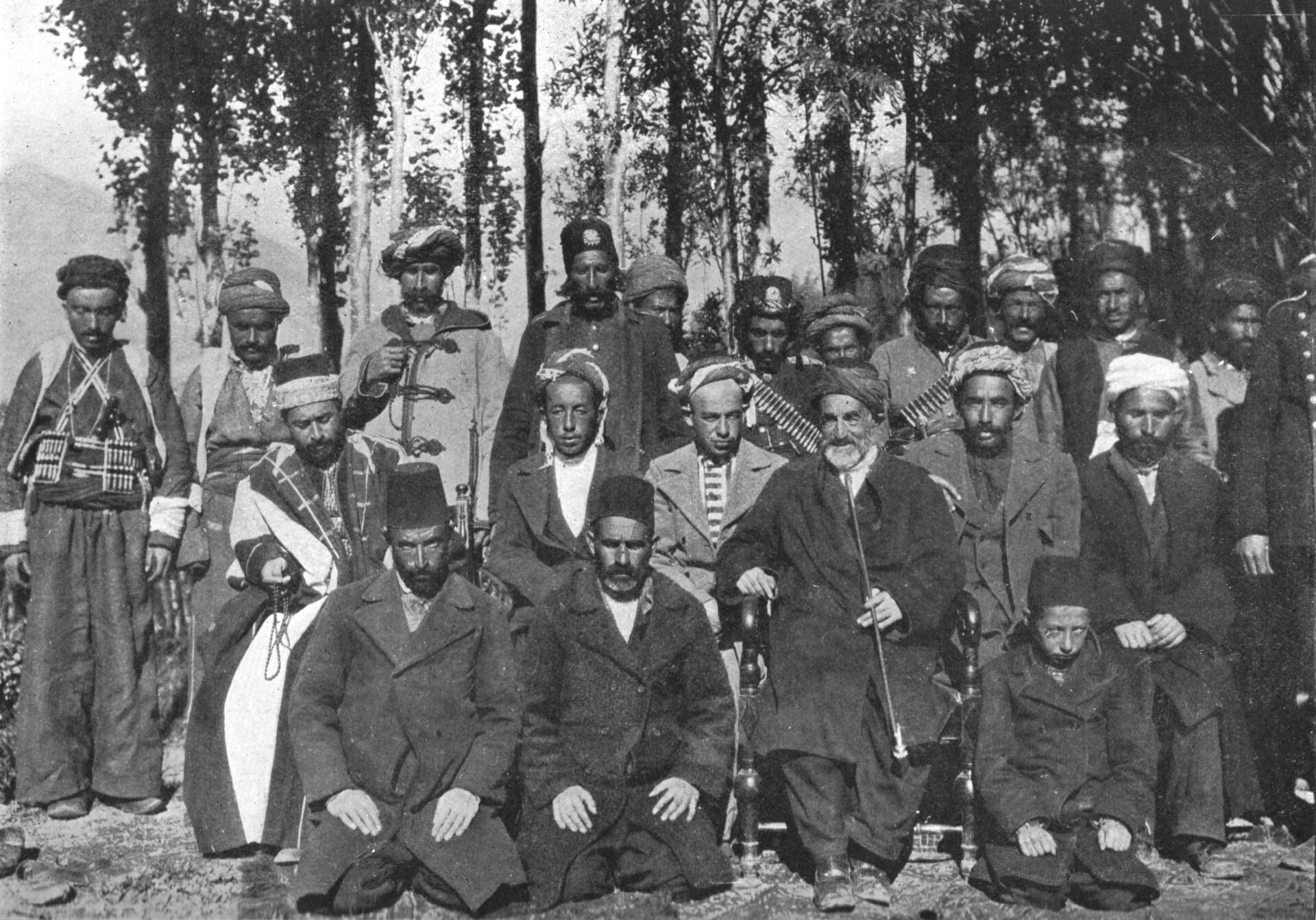

Yet Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who ruled from 1876 to 1909, changed the situation, rolling back earlier constitutional reforms. The Kurds thus found an ally in him much as they had with Selim I centuries earlier. Abdul Hamid II devised a strategy allowing the Kurds to oppose the administrative state (its officials, army and governors) while remaining loyal to the sultan personally. The sultan communicated directly with Kurdish sheikhs, often bypassing official bureaucratic channels. This period also saw the rise of the Hamidiye Brigades, a paramilitary force formed by the Kurds under the orders of the sultan. (Not all Kurds benefited, however; Yazidi and Alawite Kurds remained constant targets of Ottoman repression.)

Abdul Hamid II relied on the Kurds to counterbalance Russian influence, while the Kurds saw in the sultan a protector against the encroaching forces of modernity and reform, which had often left them marginalized. A prominent Kurdish leader of this era, Sheikh Ubaidullah al-Nahri, led a rebellion in 1880 that spanned both Ottoman and Iranian Kurdistan. His forces successfully attacked Iranian garrisons and took control of most of the Kurdish areas around Lake Urmia. The rebellion was quashed after the Ottoman government intervened to halt the Kurdish advance into Iranian territory.

The historic Kurdish-Turkish alliance, which, in one form or another, had survived for over 400 years since Chaldiran and 900 years since Manzikert, had been revived by Abdul Hamid II, who recognized that the Ottoman Empire would eventually shrink to a core centered on Anatolia. He sought to protect this core by incorporating non-Turkish Muslim groups, particularly the Kurds, into a defensive circle formed around this heartland.

The massacres of 1894-96, which resulted in the deaths of at least 100,000 Armenians, were part of this reshaping of Anatolia and Kurdistan into a Muslim entity dominated by Turks and Kurds. The Ottoman defeat in the Balkans in 1912 suggested that the empire was collapsing. Faced with this reality, the Turks and Kurds fought joint wars from 1914 to 1922 — against Russian forces in Armenia and Kurdistan, and Greek and Greek Orthodox forces in western Anatolia.

In this period the Armenian population slaughtered and deported in what many scholars regard as a genocide, despite protestations by the Turkish state, resulting in perhaps 1 million deaths (estimates vary widely above and below this figure). The conflict also led to the depopulation of Anatolia’s Greeks, who were relocated to Greece as part of a population exchange following the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. By then, the Ottoman Empire had collapsed, leaving behind a republic that reflected centuries of Kurdish-Turkish cooperation but also immense violence and demographic transformation. The alliance itself was far from total. Kurdish civilians were also forcibly displaced by Turkish forces following several rebellions, resulting in what has been estimated at hundreds of thousands of deaths.

The Ottoman Empire disintegrated after WWI and the caliph was left at the mercy of the Allied powers — Britain, France and Italy — who occupied Istanbul, the Aegean region and Cilicia. By 1919, only the central regions of Anatolia, Kurdistan and the Black Sea remained free from European occupation. From these regions, the national resistance began, culminating in the Turkish War of Independence of 1922. The Kurds once again united with the Turks, despite internal divisions between those who wanted to fight alongside the Turkish national movement and those who sought an independent Kurdish state. In the end, most opted for a common homeland. This was formalized in 1920 with the National Pact, which Ataturk drafted in consultation with Kurdish leaders. The pact was meant to create a new beginning, envisioning a joint state that would safeguard both peoples from existential threats. At that time, it contained no Turkish nationalist content. The two sides pledged that the Grand National Assembly in Ankara would work to recover territories that had fallen under British and French mandates in Syria and Iraq, including the cities of Aleppo and Mosul.

All of this was upended when Ataturk declared a Turkish republic in 1923. The Kurds rejected the new regime that denied their existence. In 1925, figures such as Sheikh Hamid Pasha led a Kurdish uprising against the republic but were felled by a brutal crackdown and executions sanctioned by the Independence Court in Diyarbakir. Despite this, in the conflict that has persisted ever since, past cooperation has served as a vision for a future of Turkish-Kurdish amity.

This vision for a united homeland was revived in the 1990s by the Kurdish leader Jalal Talabani when he proposed a historic settlement with Turkey, suggesting the inclusion of Iraqi Kurdish lands in a shared state. Similarly, Ocalan used the National Pact as the basis for a peace proposal, which laid the foundation for the peace process between 2013 and 2015. It was hoped that Turkey’s growing influence in Arab countries during the Arab Spring would be strengthened by Turkish-Kurdish peace. But the political calculations were, ironically, stymied in the summer of 2015 with the strong electoral victories of the Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), setting back Ankara’s broader regional ambitions.

In 2019, during a fierce mayoral election campaign in Istanbul against Ekrem Imamoglu of the Republican People’s Party, Binali Yildirim, the candidate from the ruling AKP, toured Kurdish-majority regions like Diyarbakir and Harput (Elazig). To appeal to Kurdish voters, Yildirim boldly referenced Ataturk’s use of the term “Kurdistan” prior to the republic’s founding, specifically to describe the Kurdish regions from which representatives came to support Turkey’s War of Independence. This moment signaled that political necessity could potentially reopen doors to peace.

Ataturk and his associates had tried to erase nine centuries of Kurdish-Turkish relations from official and academic history upon the republic’s founding. This reading is now challenged by those promoting peace. These Turkish voices argue for a more inclusive understanding of history, acknowledging the Kurdish role in the formation and preservation of the Ottoman Empire and the republic. Supported by a significant segment of the Turkish elite, they call for a recognition of the Kurdish role in salvaging what remained of the Ottoman Empire, specifically Anatolia and Kurdistan, after World War I. Kurdish proponents of this view advocate for a return to a “new charter” that would build a common homeland for Kurds and Turks, not a separate Kurdish state. This approach aims to heal the divisions that have shaped the daily lives of Kurds and Turks inside and outside Turkey, where a century of war has left lasting scars. The hope is that an acknowledgment of shared history will finally lead to political reconciliation and lasting peace.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.