With the dissolution of the Ottoman and Habsburg empires after World War I, the religious, ethnic and linguistic diversity that characterized their territories in the Middle East and Eastern Europe no longer chimed with the new world order being organized around nation-states. Some of the former imperial subjects now became minorities in a system based on an ideal of homogeneous nationalities and thus became a problem. For the powers redrawing the world map at the postwar peace conferences, and for the newly formed League of Nations, the solution involved population transfers, colonization, expulsion and various forms of state violence. Designing measures such as the Greek-Turkish population exchange of 1923, the League of Nations legitimized demographic engineering policies and made migration an intrinsic part of nation-building. With international encouragement, the states with Muslim minorities in the Balkans devised multipronged policies to push out the citizens they saw as undesirable. Turkey became the only destination for Balkan Muslims, even when they were not Turkish.

On the back of the Muslim migration of the interwar period, in 1938 Belgrade and Ankara concluded a little-known agreement to transfer 200,000 Yugoslav citizens to Turkey. The transfer did not materialize because of the start of World War II, but the migrations did eventually take place and continued into the 1950s. For both Yugoslavia and Turkey, new states created in the aftermath of World War I, migration was an important part of nation-building. Yugoslav and Turkish policies intersected as both states saw demographics as crucial for the formation of their fledgling national identities. This bilateral population transfer agreement took as its model another such deal between Turkey and Romania in 1936 as well as the better-known Greek-Turkish population exchange of 1923. European envoys and national diplomats decided on population transfers at the state and international level, with no input from the populations themselves, as if moving pins around on a map — a process infamously branded the “unmixing of peoples,” a phrase used most notably by Lord Curzon, the British foreign secretary from 1919 to 1924.

Forced processes of homogenization are still part of the repertoire of nation-state building, and continue to shape our understanding of world order. Muslim presence in the southeastern periphery of Europe likewise continues to be viewed as problematic and even dangerous: As Piro Rexhepi observed in the book “White Enclosures,” their integration continues to be desirable for security but impossible racially.

Alija Suman’s family was one of tens of thousands that migrated from Yugoslavia to Turkey in the period between the two world wars because they were Muslim. Interviewed in the last years of Yugoslavia’s existence, Suman recalled his family’s experience and how it related to the country’s beginnings. His four uncles were gruesomely murdered by local paramilitary gangs with the blessing of the authorities, in a series of massacres of the Muslim population across the region of Sandzak (which takes its name from the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, an administrative district of Ottoman Bosnia Herzegovina later divided between Serbia and Montenegro). In 1923, Suman, who was 8 years old at the time, fled with his family to Turkey from the area of Priboj. They settled in the almost exclusively Bosnian-populated Anatolian village of Kara Pazar. Within seven years, his mother and three sisters had died, as they were “not able to tolerate the climate.” Concerned for the health of the rest of his family, Suman’s father decided to return to Yugoslavia, but the Turkish authorities did not allow them to travel back. It was only after they hired a lawyer in Istanbul that they managed to get a passport with a six-month visa, returning to Yugoslavia for good in 1930. Most migrants, however, did not return.

Addressing the Turkish Grand National Assembly in 1922, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, modern Turkey’s founder, and of Balkan origin himself, defined the incoming Balkan migrants as “our coreligionists who sought refuge from the regions that remained beyond our national borders.” Focus on religious identity allowed for a formal incorporation of these rather diverse populations into the Turkish national body. The asylum policy and the settlement laws defined migrants as Turks and those “affiliated with Turkish culture” to encompass all the Slav, Albanian and Greek Muslims, making Turkey a safe haven for Muslim minorities fleeing oppressive regimes.

Dispossession, expulsions and massacres of diverse Muslim populations were already a grim reality of nation-building in southeastern Europe in the 19th century, when Greece, Montenegro, Serbia, Romania and Bulgaria were carved out of Ottoman provinces. In fact, the conquests of Ottoman Europe after 1699 normalized expulsion and compulsory conversion of local Muslims in the lost territories. By the turn of the 20th century, the outcome was evident: Muslim populations were significantly diminished or entirely erased; Islamic and Ottoman architecture was obliterated; and names of places changed. During the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria invaded the remaining Ottoman territories in Europe. Within several months, an estimated 1 million Muslims vanished, murdered and expelled from the regions taken over by these states. The shocking magnitude of the violence, which continued into World War I, made many Muslims wary of their future in the new nation-states and incited migration to the Ottoman Empire, itself in the midst of conflict.

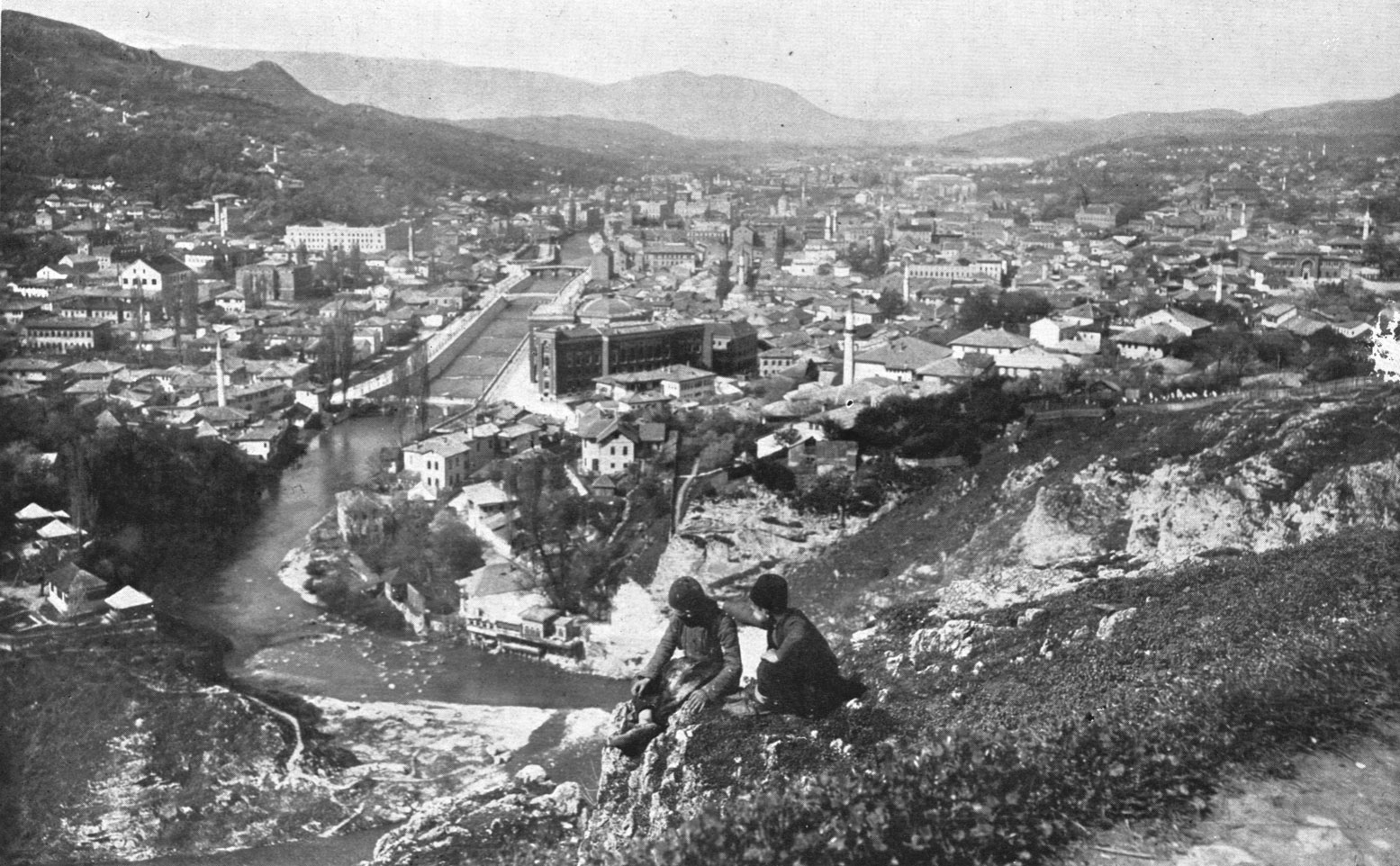

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, was formed in 1918 as the culmination of South Slavism — the notion that Slovenes, Croats and Serbs were one nation. Yet the Yugoslav lands incorporated a linguistically, religiously and ethnically diverse population. Its Muslims comprised majorities in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Southern Serbia. They were also ethnically and linguistically diverse, including Bosniaks, Albanians, Turks, Torbesi, Gorani and Roma. Since the kingdom was created as a nation-state of the South Slavs, its non-Slavic populations were not its intended constituents. Even its Slav Muslims were not included because of their religion. Edin Hajdarpasic’s book “Whose Bosnia?” has shown that 19th-century definitions of South Slavic brotherhood envisioned Slav Muslims as potentially assimilable, distinguishing between “the Turks” as the non-Slavic Ottomans and “our Turks,” that is, Slav Muslims. Hajdarpasic conceptualizes this process as (br)othering, revealing that the nationalists continually redefined a binary “us” and “them” construction.

Yet that did not prevent the outbreaks of violence and discrimination directed at Slav Muslims in the Yugoslav Kingdom. Several hundred Montenegrin Muslims were massacred in Sahovici in 1924. The murderers, locals aided by district officials, seized their houses and land without consequence, while the survivors were forced to resettle in Bosnia and Turkey. The news of massacres spread quickly. To avoid a similar fate, the leaders of another town offered to vote for the ruling party and to encourage Muslim migration to Turkey. In the 1920s, Catholic missionaries working in neighboring Kosovo, a former Ottoman province inhabited by Albanian Muslim and Christian populations and similarly incorporated into Southern Serbia, sent reports of massacres, assassinations, imprisonment and forced labor in a memorandum to the League of Nations, receiving no response. Entire villages migrated when the authorities offered no recourse, in part because the perpetrators were often the representatives of the Yugoslav government themselves.

Majority Muslim regions were also targeted for intensive land appropriation under the pretense of land reform, a measure that would weaken communities economically and ultimately lead to further migration. This was most intensive in Kosovo and western Macedonia, where the areas bordering Albania were dominated by Albanian Muslims, and was fueled by Yugoslav anxieties over its neighbors’ potential land claims. Small and large landowners experienced this land reform as property confiscation, intimidation and ransom, and were often left without enough land to sustain their families. The so-called reform also included the vast properties of the Islamic pious endowments. Schools, mosques and Sufi lodges lost the land and incomes that were used to operate educational, religious and community services. Some land appropriations were symbolic: The 15th-century Burmali Mosque that visually defined Skopje’s main thoroughfare was simply torn down. The breakdown of the social and economic fabric of Muslim communities, together with the emblematic changes in their lived environments, were compounded by discrimination and consistent othering in the new state, leaving them with few choices for a dignified life.

The Yugoslav Kingdom recognized the religious but not the ethnic and linguistic diversity of its Muslims, and offered them limited or no political representation. In a vicious cycle, Muslims were then considered backward for their inability to develop national consciousness. Diverse Yugoslav Muslims were labeled “Turks,” with a derogatory bent. Although a term with a longer history in the European context, in the world of Balkan nation-states, “Turk” became a useful tool for othering, thus making migration to Turkey a logical consequence.

Ivo Andric, an admired novelist and Yugoslav Nobel laureate, was also one of the highest-ranking Yugoslav diplomats in the interwar period. Eager to finalize the population transfer agreement with Turkey, he advised the government in Belgrade that Turkey was not only interested in the small group of ethnic Turks in Yugoslavia but also populations akin to Turks in their “mentality.” Repeating a constant theme in almost all of Andric’s novels, Muslims were described in his diplomatic correspondence as alien to the Balkans. For Andric, they were “Turks leftover in the territories of our Kingdom.”

Traveling within Yugoslavia in 1936, Ahmet Emin Yalman, a prominent Turkish journalist, found that Yugoslav administration “oppressed the Turks less” than the other Balkan states. He noted in his report to Turkish Prime Minister Ismet Inonu that Slav Bosnians saw Turkey as a “spare” homeland, in case they were forced to migrate. But the Turks living in the south of the country were like colonized peoples: Having lost their land, they worked in petty occupations at the bottom of Yugoslav society. Yalman reasoned that migration to Turkey was then the only way to recover from this “spiritual and material death.”

The process of leaving Yugoslavia was made easy. Former Ottoman, non-Slavic citizens could renounce their citizenship by providing a statement to the local authorities, after which they had a year to leave, according to the Yugoslav citizenship law. However, when local authorities abused their position by issuing travel documents in exchange for large sums and entire properties, potential migrants sought other ways to travel. A number of Yugoslav citizens went to Salonica at the time of the Greek-Turkish population exchange, hoping to be resettled to Turkey. In one such instance, Turkish authorities found that over 2,000 Bosnians were settled along with Greek Muslims in the town of Izmir.

Thus, Muslim migrants from Romania, Bulgaria, Greece and Yugoslavia came to Turkey in overwhelming numbers in the interwar period. Because they experienced similar treatment in their home countries, Balkan Muslims often arrived in Turkey with modest means and had to rely on aid from the state which itself had little to offer. Turkish officials, faced with the constant influx of migrants, pursued agreements with the Balkan states that would offset the costs of migrant settlement. The 1934 Balkan Pact included minority clauses that allowed Turkish citizens to sell their properties in their former homelands. Turkish administrators also considered requesting an estimated payment from the Balkan nation-states to match the value of the properties that Balkan Muslims were forced to leave behind.

This reasoning was employed in the population transfer deliberations with Romania and Yugoslavia in the 1930s. The transfer between Yugoslavia and Turkey was to commence in 1939 and encompass 200,000 people from southern Yugoslavia over a six-year period, while Turkey was to receive 20 million lira in property compensation. The two states negotiated to transfer Turks, but the Yugoslav prime minister was pleased that the vague wording of the agreement allowed for the possibility of “tossing in a larger number of Albanians.” Although the transfer never materialized, migrations continued, with anywhere from 60,000 to 150,000 Muslims migrating in the interwar period from Yugoslavia to Turkey. Balkan migrants relocated to Anatolia and Thrace, whose citizens were recovering from a decade of war — the Balkan Wars (1912-13), World War I (1914-18) and the Turkish War of Independence (1919-22). The Turkish Republic saw population growth as beneficial for economic development and national defense in the long term, as it worked to populate its eastern and western borderlands. Moreover, many of Turkey’s early administrators, as migrants and children of migrants themselves, understood these new waves of migration from a personal perspective.

Turkey provided assistance, tax and military service exemptions to make the immigrants independent, seeing them as prospective citizens to be integrated into the nation. Laws barred those speaking languages other than Turkish from settling in groups and limited the “foreign” presence to no more than 10% of a municipality, though the realities of the period frequently made these laws impossible to execute. The locals took on much of the burden of helping newcomers, begrudgingly sharing public resources. At the same time, the immigrants provided necessary manpower and introduced new methods in agriculture and certain industries. While Balkan languages largely disappeared with the following generation, enduring legacies, such as Balkan cuisine and music evoking the most personal memories of exile, acquired a place in the Turkish national heritage.

Nation-building after the Great War normalized migration, colonization and population transfers and exchanges, as demographic scale came to define the status of nations and the extent of their borders. In southeastern Europe, these processes were incomplete and entailed violence and discrimination against Muslim minorities throughout the 20th century, culminating in genocide and ethnic cleansing in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo in the 1990s. Today, no official recognition of the violent policies of “unmixing” exists, and barely anyone has heard of Yugoslavia’s attempted population transfer of 1939. Histories of the region fail to capture the continuity of successive state policies toward its Muslim communities, with stories like Alija Suman’s fitting awkwardly into narratives that privilege individual nation-states and uniform ethnic groups. Eerily similar to the logic of the League of Nations a century earlier — and in spite of civil societies and political options that today reject such divisions — the international community’s preferred solutions to “ethnic conflicts” in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo remain equally tied to principles of nationalist homogenization and demarcation. A century after the foundation of modern Turkey and the first Yugoslavia, the legacies of that era’s mass migration and state violence persist.