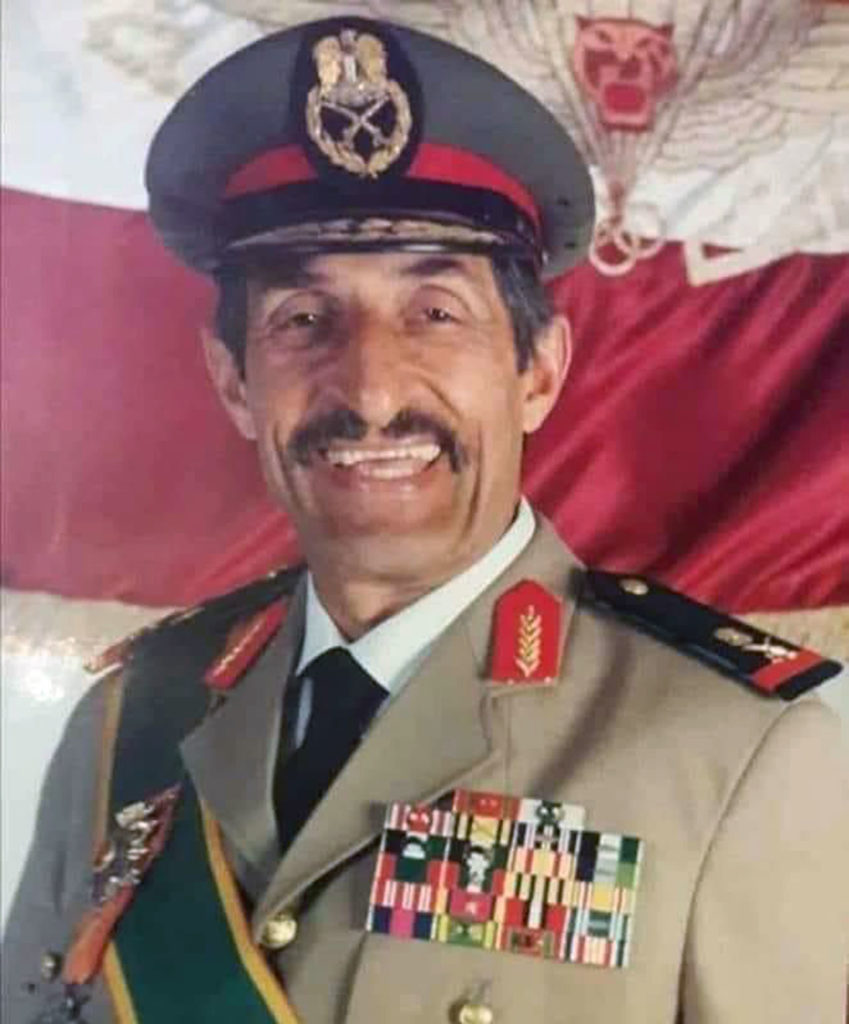

In the mid-2000s, mosque goers in the highest village in the Alawite mountains in western Syria would notice an aging man with a dark complexion and a thick mustache sitting in the corners, regularly attending Friday sermons. The mosque imam in the village of Hallet Ara, in Jableh, would sometimes hand him the microphone at the end of sermon to speak to worshippers. He would preach about spirituality and religion, with the heart of a man who appeared as if he had spent his entire life reading and memorizing the Holy Quran. Except this man was Ali Haydar, a retired general from the secular Syrian army who had helped Hafez al-Assad seize power in 1970.

For 25 years, he was one of the most feared and ruthless officers, having waged many wars during his lifetime, against Israel, the Palestinians, the Lebanese Phalange and the Syrian branch of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. He was now retired, or rather discharged, spending his retirement at the local mosque in his native village, after having reportedly become deeply religious. On Friday, Haydar died at his village home, aged 90.

Outside Syria, and despite his key role in several regional events and in many of the wars that involved the Assads’ Syria, his death was barely noticed. In Syria, Haydar is remembered by opponents of the Baathist regime as one of the creators of a brutal and repressive state, while being hailed by regime supporters as a hero representing a bygone era of effective officers who kept Syria together.

Regime supporters celebrate his legacy as a member of the Old Guard, from the good old times when Syria was stable, secure and internationally recognized. Young Alawites (of the Muslim religious minority sect to which the Assads belong) eulogizing him say he is the “father of the Special Forces [“Al-Wahdat al-Khasa”],” a once omnipotent force that has been recently sidelined and dwarfed by the more powerful Republican Guard and the 4th Division. The Special Forces are associated with victories, back in the 1970s and 1980s against the Islamists, not in this present war, and under Assad the father, not the son.

Many of the officers celebrating his legacy grew up under his patronage or were inspired by him. These officers were as brutal as he was, but they conducted themselves differently from how he did.

Haydar had no life other than the military barracks. He was rarely seen at parties and restaurants, never with the business community or with actors and artists. That was in stark contrast to the new generation of officers, who put on the facade of being modern, civilized and trendy — wearing stylish sunglasses, engaging with followers on Facebook and appearing in public with television celebrities. In the decade leading up to the momentous events of 2011, the new generation did not need to show publicly that they were as brutal and repressive as Haydar’s generation, and this gave a false sense of softness and rationality, which is probably why many Syrians underestimated how brutal they could be when challenged for the seat of power.

Haydar would have given them no such illusions. He was willing to kill anybody who threatened the regime — and he did not hide it. There was a rebellion against the Baathist rule in 1982, and when that failed, nobody tried it again during his tenure at the Special Forces.

That is his legacy for regime supporters. He is otherwise remembered as one of the most iconic figures of the Baathist regime established by Hafez in the 1970s and continued by his son Bashar, and one of the makers of this regime’s repressive machine. The dichotomy in the way he is remembered captures what Syria is facing even as the violence largely ceased across the country.

Many villagers were not surprised by Haydar’s turn to religion, given that he hailed from a well-known, middle-class Alawite family of religious sheikhs. His father was a sheikh and so was his uncle, Ahmad Mohammad Haydar, who made a name for himself in the 1930s as a religious “reformer,” calling on Alawites to abandon superstitions and blend with mainstream Islam. The Haydars were from the powerful Haddadin clan of the Alawite community, which includes the family of Anisa Makhlouf, the mother of the current president. It was into this family that Haydar was born in the era of an Alawite enclave known as the State of the Alawites in 1932, under the French Mandate. He attended government schools in Latakia, a two-hour walk from Hallet Ara, where he met Hafez, a fellow Alawite student, sometime in 1951. They were to become lifelong friends and jointly entered the Baath party in the mid-1950s, at the urging of their teacher Wahib Ghanim, who had served as a cabinet minister during Syria’s democratic years. Hafez was two years Haydar’s senior, and they enlisted in the Homs Military Academy, graduating to become professional soldiers in the Syrian army.

Both were enchanted by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who preached Arab nationalism in the 1950s, supporting him with the creation of the Syrian-Egyptian union in 1958. During the union years (1958-1961), Hafez was posted to Cairo, while Haydar remained in Syria. For some reason, he was left out of the secret military committee founded by Hafez and his Baathist comrades in 1959, which was to defend the union from “its many enemies” (a term they used in reference to the United States, Israel and Saudi Arabia). The union regime was toppled by military coup in 1961, and less than two years later, Hafez took part in another coup with Nasserist officers, aimed at restoring the United Arab Republic. It was staged on March 8, 1963, making Hafez the commander of the Syrian air force. On Feb. 23, 1966, another coup took place in Damascus, bringing Alawite strongman Salah Jadid to power. He too was a founding member of the Baath Party Military Committee and had briefly served as chief-of-staff of the Syrian army after what the regime calls the March 8 Revolution.

Jadid was an introvert who spoke little and never gave a public speech. Well aware of his weakness as a member of a minority sect, he didn’t assume direct control of the state, instead propping up a puppet medical doctor named Nureddin al-Atassi, as president. Hafez became minister of defense under the Jadid-Atassi government, and in the aftermath of Syria’s defeat in the Six Day War against Israel in 1967, he commissioned the creation of a special shock force to engage the Israelis in what Nasser called a “War of Attrition.” They were named the Special Forces and were put under the command of his longtime friend Haydar, who was 36 and until then had assumed no senior post under the Baath regime. The war of attrition plan was the brainchild of Nasser, who believed that only such tactics would force Israel to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank and the Syrian Golan Heights, all of which had been occupied within a week in 1967. The War of Attrition was launched officially in March 1969 and included commando raids by the Syrian and Egyptian armies into Israeli territory. From his headquarters in Al-Qutayfah in the countryside of Damascus, Haydar began preparing his troops for a much larger role in the history of contemporary Syria.

On Nov. 17, 1970, Haydar’s Special Forces took part in a military coup led by Hafez, arresting Atassi along with the real boss in charge, Salah Jadid. They were both sent to jail for life. Atassi was only released weeks before his death in 1992, while Jadid died in his prison cell the following year. Haydar became part of Hafez’s inner circle and was known to be one of his most trusted and reliable officers. In 1973, Haydar’s troops took part in the October War with Israel, where they were involved in taking an Israeli observation base on the southern slope of Mount Hermon.

Two years later, the Special Forces were called into battle again, this time to fight the PLO of Yasser Arafat, early into the Lebanese Civil War. Haydar’s forces crossed the border into Lebanon on June 1, 1976, and set up a military base in Bhamdoun, some 15 miles from the Lebanese capital, Beirut. Another unit was established in the Bekaa Valley and a third in the northern city of Tripoli. Once through with fighting Arafat, Haydar turned his guns against the Lebanese Phalange party of Bashir Gemayel, after they welcomed the 1982 Israeli occupation of Beirut with the hope of eliminating Palestinian military presence in Lebanon.

In between both Lebanon battles of 1976 and 1982, Haydar was elected to the 75-member Central Committee of the Baath party during the Seventh Party Congress held between December 1979 and January 1980. His men were briefly engaged in domestic fighting, for the first time since the creation of the Special Forces in 1968. Since 1976, the armed wing of the Muslim Brotherhood had begun to strike at Alawite figures, killing scores of doctors, engineers and officers close to Hafez. Haydar was high on their list of targets. In 1980, he was ordered to comb the cities of Homs, Aleppo and Jisr al-Shughour, where pro-Brotherhood sentiment was high, using tanks, airplanes and commando units. Thousands were arrested on the slightest suspicion of being members or even sympathizers of the Brotherhood. They were hauled off either to jail for the rest of their lives or to be summarily executed.

This campaign culminated with the final battle with the Muslim Brotherhood in Hama, on Feb. 2, 1982. A siege was laid on the city, and it was sealed off from the rest of Syria for 27 days. There are no specific numbers of how many people died during that period. In his 1990 book “Pity the Nation,” the late British journalist Robert Fisk mentions 20,000 dead in Hama. The Syrian Human Rights Committee gives a much higher figure, saying that between 35,000 and 40,000 people died in Hama.

Although Haydar came to be associated with the Hama military operation, he was not alone. Other officers who had a central role in the battle included Col. Fouad Ismail of the 21st Mechanized Brigade and Nadim Abbas of the 47th Tank Brigade (which was part of the Third Armored Division of his friend and comrade, Maj. Gen. Shafik al-Fayyad). And of course, primary among them was Rifaat al-Assad, the current president’s notorious uncle, who commanded the all-powerful Defense Forces. Anywhere between 12,000 and 25,000 troops were involved in the Hama battle, which ended with the destruction of much of the city and the eradication of the Brotherhood from Syrian society until it regrouped and reemerged as a political and armed entity after the 2015 fall of Idlib and its environs, 30 years later.

In 1983, Hafez became seriously ill, triggering a succession crisis within his own family. Before checking in to hospital, he had created a ruling body to run state affairs in his absence, composed entirely of Sunni Muslims like Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass, army Chief-of-Staff Hikmat Shihabi and Prime Minister Abdul Rauf al-Kasm. Rifaat, long-considering himself as Syria’s number two, was left out of the council. That triggered his vengeance while awakening his political ambitions. He ordered the Defense Forces to the streets of Damascus, preparing for a coup. His photos were plastered across the city with the name in which he loved to refer to himself: “al-Qaid” (The Leader).

Haydar would prove instrumental in this episode too. In terms of training, strength and arms, Rifaat’s Defense Forces were matched by no other unit in the Syrian army, except for Haydar’s Special Forces.

In his seminal book “The Struggle for Power in Syria,” Dutch ambassador and historian Nikolaos Van Dam says that Haydar’s force was 45% Alawite among soldiers and 95% Alawite among officers, whereas Rifaat’s Defense Forces were 90% Alawite at both levels. Van Dam puts the overall number of Haydar’s forces between 8,000 and 15,000 men, while Hafez’s British biographer Patrick Seale says that they numbered between 10,000 and 15,000.

Rifaat tried luring Haydar into an alliance, which, had it happened, would have certainly toppled Hafez 10 years into his presidency. Haydar refused to be part of the conspiracy, however, telling Rifaat: “I recognize no leader in this country other than Hafez. He is my benefactor. What I have of power and prestige I owe to him. I am a soldier in his service and a slave at his beck and call.”

Far from siding with Rifaat, Haydar ordered his troops into the capital as well, stationing them at strategic corners in preparation for a showdown with the Defense Forces. The bulk of his troops were stationed around the television headquarters in Umayyad Square, which is usually the first destination for any coup mastermind, strategically seated next to the army headquarters. Rifaat’s men were identified by their crimson berets, Haydar’s by their maroon berets. When Hafez recovered and checked out of hospital, he famously went to his brother’s home on Mezzeh Autostrade, accompanied by his eldest son Basil. In a family confrontation attended by their aging mother, Assad told his brother: “You want to overthrow the regime? Here I am. I am the regime!”

With the help of his Soviet allies, Hafez decided to send all of his top generals to Moscow, ostensibly as part of a government delegation, until tensions cooled off. They were dispatched on a one-way ticket, with no clue as to when or how they would return. Before leaving Damascus, Rifaat hosted a farewell reception to his supporters at the Sheraton Hotel, saying: “Had I been foolish, I could have destroyed this whole city, but I love this place. The people are used to us; they like us. And now these commandos [referring to Haydar and his men] want to chase us out.”

Haydar and Rifaat were put on a charter flight to Moscow on May 28, 1984. Joining them were officers Fayyad and Mohammad al-Khouly, head of the Syrian air force. One by one, Hafez summoned each of them back to Damascus, keeping Rifaat alone away from home. He was sending a message: I have made you all, and I can banish or destroy you, whenever I want. I can also bring you back — if I want. Hafez eliminated all of his enemies and tightened his grip on power multiple times over the years, and Haydar was instrumental almost at every corner.

Haydar remained loyal and by Hafez’s side during the 1980s and early 1990s. Cracks began to appear after the start of the Middle East peace process, which commenced at the Madrid Peace Conference in October 1991. The USSR was falling apart and Syria was turning a new page with the U.S. administration of then-President George H.W. Bush. Hafez took the decision to go to Madrid and enter into direct talks with Israel, without consulting any of his top lieutenants. He didn’t feel he had to — every strategic decision since 1970 had been taken single-handedly by the president, and nobody in his inner circle dared object or question his wisdom. Haydar, however, reportedly complained before a group of officers, saying, “We who have built the regime want a say in the peace process.” That remark was passed on to Hafez and upset him for two reasons. One was the visible dissent from one of his senior officers, but more importantly was that Haydar was now seemingly viewing himself as a partner. Hafez saw these men as his creation, as pawns and subordinates, never as partners or co-creators.

Then came the death of Hafez’s son Basil in a car crash in January 1994, on his way to catch a plane at Damascus International Airport. No sooner had the funeral passed than Hafez began planning for Basil’s succession, bringing his second son Bashar from medical studies in London for a crash course in military and political affairs. Bashar was 29, Haydar was 62. Again, Haydar raised the president’s ire by reportedly saying: “First it was Basil and now Bashar. We are more worthy than these boys.”

That was the kiss of death for Haydar.

On Aug. 3, 1994, seven months after Basil’s death, he was arrested, discharged from the army and from all posts in the Baath party. Command of the Special Forces was given to Gen. Ali Habib, another Alawite officer who had led Syrian troops in the second Gulf War of 1991. Haydar was kept in captivity for two months, in a location that until today remains undisclosed. Nobody knows exactly what happened during those months and whether he ever sat down one-on-one with Hafez. What we know is that Haydar was eventually pardoned, released and allowed a dignified retirement with no court or smear campaign.

He showed up for Hafez’s funeral on July 13, 2000, and publicly pledged allegiance to Bashar as the new president of Syria. When the Syrian revolt started in March 2011, social media networks ran wild stories about Haydar saying that he was opposed to the manner in which the war was being carried out, and to what he reportedly described as the “senseless killing” of young Alawites because of an avoidable war. None of these stories seem true, judging by Haydar’s peaceful death and the amount of homage he received on the day of his passing from pro-regime websites and news outlets.

But they do point to the schism that remains at the heart of Syrian society, one that has persisted into the second generation of regime soldiers, namely whether the regime created a brutal and repressive state or an apparatus of control that kept Syria whole in a difficult neighborhood. Haydar was very much on one side of this, believing in the “stability” of the regime, despite his close involvement in wars and repression. Even after the 2011 events, it doesn’t seem as if he changed his mind. He leaves behind a large family, an Assad regime determined to hold on to power and a country in tatters.