Eighty years after Oradour-sur-Glane was burned to the ground, traces of those who lived there remain. The streets are strewn with bed frames, bicycles and the occasional car, frozen in time. And there are sewing machines, dozens of them, lying where they were last used, littered among the ruins of the small French village.

It was here, on June 10, 1944, four days after the Allies first landed in Normandy, that 643 civilians, including 247 children, were shot or burned alive by retreating Nazi troops. Visitors say the smell of smoke still lingers in the air.

On June 10, 2024, Emmanuel Macron came to pay homage to the dead in the fully preserved village near Limoges.

“We must confront our history,” the French president said in his speech. A few minutes later, as Macron walked through the charred ruins, a reporter from the French daily Le Monde overheard him speaking to a businessperson.

“I’ve pulled the pin and lobbed my grenade right in the middle of them,” the president reportedly said with a pleased smile. “Now let’s see how they cope.”

On this, the site of the worst massacre of civilians by the Nazis in occupied France, Macron’s crass, warlike remark rankled. To understand it, we must go back in time — to the previous night, and to the first half of the 20th century.

On June 9, one hour after suffering a crushing defeat at the hands of Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally (RN) in the European parliamentary elections, Macron unexpectedly announced the dissolution of the National Assembly and called for snap elections to take place on June 30 and July 7.

The unpopular president, whose candidates had received less than half as many votes as Le Pen’s opposition party, described this shock move as an “act of confidence.” He hoped that the deep divisions on the left, further entrenched by the chaotic European campaign, would make him — as they had in 2017 and 2022 — the only alternative to the far right.

But he was wrong.

Macron’s explosive announcement opened a road to the revitalization of the left. Faced with the risk of a far-right parliamentary majority and prime minister, 25 left-wing parties chose unity. Just a few days after the dissolution, the New Popular Front was born.

The pact’s name harks back to the left-wing alliance that came together in the wake of the Great Depression and as a reaction to the rise of fascist regimes across Europe. Though short-lived, the coalition governed France from 1936 to 1938 and achieved key social victories, such as paid vacation leave and the 40-hour week. Eight decades later, the Popular Front remains firmly rooted in the political mythology of the French left.

So powerful is the memory of the Popular Front that by 10:15 p.m. on June 9, not two hours after Macron announced the dissolution, it had already been made into a rallying cry. On Twitter (which we Frenchly refuse to call X), Francois Ruffin, a lawmaker from the radical-left France Unbowed party, wrote: “A single banner: Popular Front.”

On live TV 10 minutes later, standing in an unlit street outside his office, Ruffin declared: “Let us cut the bullshit. … History shows us that the crisis of 1929 led to Nazism in Germany but that in France, it led to the Popular Front.”

That night and the following one, some 3,000 left-wing activists gathered on the Place de la Republique in Paris to call for unity. “Tonight, the Popular Front is my earnest hope,” said Juliette, an 18-year-old high school student carrying a pride flag. Her mother concurred: “They’ve done it before; they can do it again!”

There is no doubt that this election will be historic, with the power to make or break French democracy. (In an “autocratic stress test,” experts estimated that a French authoritarian regime would need only 18 months to change the constitution and upend the rule of law as we know it.) But this campaign is also a historical one, deeply anchored in the memory of the 1930s and 1940s.

Then, just as now, France grappled with a global economic and financial crisis. Then, just as now, the country had to contend with the rising ambitions of fascist movements at home and totalitarian regimes to the east. The parallels are striking. And though the three historians interviewed for this piece refute any notion of history repeating itself, they are adamant that understanding the successes and failures of the original Popular Front offers valuable lessons for today’s coalition.

Antoine Jourdan was meant to be on vacation this month — “a hard-won social achievement we owe to the original Popular Front,” he quipped. Instead, the historian told New Lines, he has been fielding calls from reporters hoping to put France’s new left-wing coalition in its historical context.

When he picked up the phone, the 28-year-old doctoral student sounded ecstatic. “It’s a beautiful, powerful reference,” Jourdan exclaimed, “and a happy one at that!” The Popular Front, he said, was above all a moment of popular joy.

“There’s happiness for everyone,” sang Maurice Chevalier in 1936. “There’s joy!” concurred Charles Trenet one year later — “The Eiffel Tower’s going for a stroll. She jumps into the Seine with both feet, like a mad woman.”

The joy and optimism of the Popular Front, Jourdan told New Lines, were born out of “marasmus.” In French, the expression refers both to severe undernutrition in children and deep apathy. France in the early 1930s exhibited signs of both.

The Great Depression, which had brought the United States to its knees in 1929, only really hit France two years later. Revenue rapidly declined, unemployment rose, and the 1932 elections ushered in a government committed to cutting costs. When this failed to improve the state of the country, instability ensued, with more than half a dozen men holding the position of prime minister in 1932 and 1933. By 1934, 1 in 6 male citizens were unemployed.

Far-right leagues and royalists blamed the parliamentary government. On Feb. 6, 1934, a year after Hitler’s rise to power in Berlin, right-wing paramilitary groups came frighteningly close to overthrowing the government in Paris. The Camelots du Roi, the shock troops of the nationalist and royalist Action Francaise, tried to smash their way through to the assembly but were stopped by the police at the Place de la Concorde. The protest — 14,000 strong — soon turned into a riot, with 16 dead and some 1,500 wounded. The political leadership and activists both believed the demonstration had been an attempted coup, Jourdan told New Lines.

“Much like in 2024,” he added, “the Popular Front was born out of fear, but the seeds of unity were planted at the grassroots level.”

Last month, only 10 hours after the dissolution of the assembly, young voters camped out in front of the Green Party headquarters, where left-wing leaders had met to discuss a potential union. “Make a deal!” they chanted under the open windows, “Do not betray us!” After hours of negotiations, the heads of the four biggest left-wing parties, who had not been seen together in 10 months, finally came out of the building. “We’ve done it!” proclaimed a beaming Marine Tondelier, leader of the Green Party.

On the other side of the country, in Marseille, activists immediately erupted into song: “Put your hands in the air for the Front Populaire!”

After the 1934 riots, grassroots left-wing militants had also called on their parties’ leaders, begging for unity. Unlike now, they had two years, not three weeks, until the legislative elections — but the rift between the opposing parties was immeasurably wider.

For years, the two camps — Stalinist communists and socialists — had been “fraternal enemies,” Jourdan explained. The first were dubbed “social fascists,” the second “social traitors.” In the wake of the riots, each party organized its own protest. The two processions were kept separate. That is, until activists on both sides joined one another and cried: “Unity! Unity!”

In his memoir, Leon Blum — who would go on to lead the first Popular Front government — wrote: “The gap between the two front lines diminished by the second and the same anxiety gripped us all. … The two front lines were now face to face and from all sides the same cries burst forth. The same songs were taken up in unison. Hands were shaken. The front lines merged. It was not a collision, it was fraternization.”

The 1934 riots had served as a “wake-up call” over the risks of disunity. Leaders and activists needed only look to the east, where left-wing parties had failed to come together: The Communist Party had been banned a mere day after Hitler’s accession to the Reichstag, and by 1934, political opponents were already being shipped off to the Dachau concentration camp.

In France, the “left-wing cartel,” which had governed since 1932, fell in the wake of the riots. With Germany as a cautionary tale, Jourdan told New Lines, France became “the laboratory of a new alliance, between socialists, communists and radical democrats.”

First came the Watchfulness Committee of Antifascist Intellectuals, founded in March 1934. They published a newsletter, “Vigilance,” and boasted more than 6,000 members by the end of the year.

Jean Vigreux, a historian and author of “The Great Escape: A History of the Popular Front,” spoke to New Lines with clear enthusiasm about this feature of the time: “Intellectuals played a key role in the unification of the three left-wing families in 1934. And so too must they in 2024.”

Vigreux, who has given some 30 interviews since talks of a New Popular Front began just a few weeks ago, spoke rapidly and with the fervor of an activist.

“Now is not the time for coyness or ivory towers,” he said. Like some 1,000 of his colleagues, he signed an op-ed calling on France not to turn its back on its past and to form an alliance against the far right.

The RN’s whopping victory in the European elections reactivated those old reflexes, Vigreux said with evident pride.

“The hopes of an anti-fascist alliance have evidently been revived,” he added.

After the intellectuals came the communists. In the summer of 1934, alarmed at the increased popularity of fascist regimes across the continent, the Comintern chose to abandon its hostile position toward social democracy and parliamentary government. The French Communist Party was instructed to begin talks with the socialists. And so the name “Popular Front” first appeared in L’Humanite, France’s communist newspaper.

Blum answered the call in socialist daily Le Populaire, vowing that this new alliance would have a shared goal: to defend the “array of freedoms [which] are the basis of what we call democracy.” In 1935, they were joined by the center-left Radical Party — France’s most popular party.

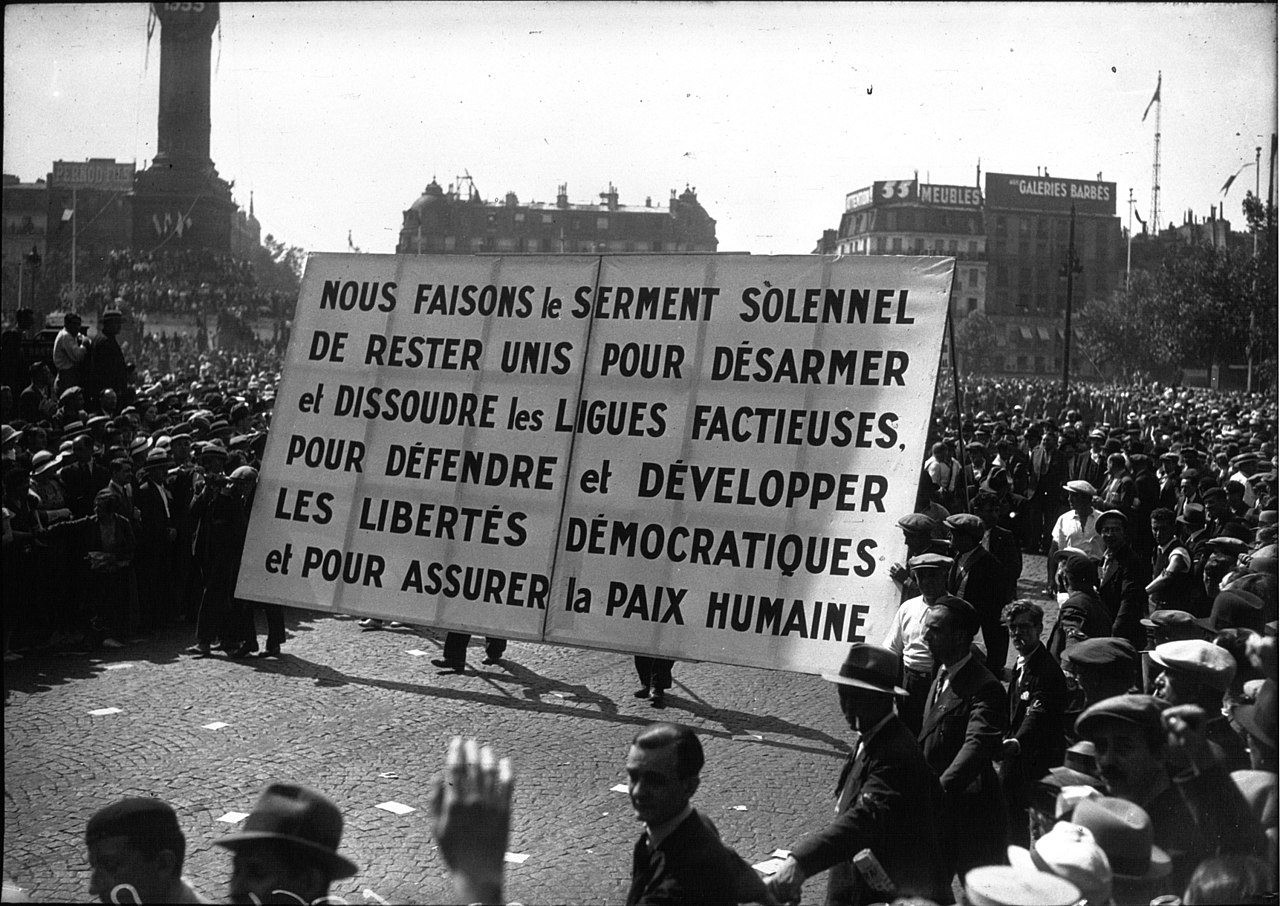

On July 14, 1935, communists, socialists and radicals came together in a united protest that gathered some 500,000 sympathizers. The Popular Front was officially born, on a deeply symbolic date — the anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille in 1789, a key moment of the French Revolution — and site — the Place de la Concorde, where the 1934 riots had shaken the city. In Paris and across the country, attendees made a common pledge, spelled out on giant banners: “We take the solemn oath to remain united to disarm and dissolve the factional leagues, to defend and develop democratic liberties, and to ensure peace.”

“Bread, Peace and Liberty” became the slogan of the Popular Front.

Bolstered by this historic march, the economic crisis and the absence of a cohesive alternative from the right (whose main campaign argument was staunch anti-communism), the Popular Front won a clear victory in the legislative elections in the spring of 1936. Blum became the first socialist prime minister of France (and the first Jew to hold that office).

Before Blum could even form his government, a series of strikes upended the country. Years of social frustrations and the high hopes raised by the Popular Front’s victory brought the country to a halt. The speed and magnitude of the strikes took even party leaders and trade unionists by surprise. In May and June 1936, 12,000 strikes brought together some 2 million workers. Some walked out; others simply sat down and occupied their factories, for days on end.

“The French revolution has begun,” wrote Leon Trotsky, rather optimistically.

This revolution soon turned into a nationwide party. Workers dressed in drag and danced the jig on factory floors to the warm voice of Maurice Chevalier. Philosopher Simone Weil, then 27 years old, joined the workers and recounted the experience in the trade unionist magazine La Revolution Proletarienne: “After bending and enduring always, enduring everything in silence for months and years, this strike is about finally daring to stand up, to speak to one’s turn, to feel human for a few days. … This strike is in itself a joy. A pure, unadulterated joy.”

“Rather typically,” Vigreux quipped, “the French put class warfare to the sound of the accordion.” The sit-ins worked, and the strikes put Blum in a position to negotiate.

That summer, the upper-class vacationers of Deauville, Nice and other French resorts were horrified. Alighting at the seaside from the cheap compartments of trains were crowds of workers on their first paid holidays, waving their tickets in the air — the so-called “Lagrange tickets,” named after the minister for sports and leisure.

“Suddenly,” Vigreux told New Lines, “social democracy came to enrich liberal democracy.”

In the collective imagination, the Popular Front remains firmly linked to the memory of that summer, immortalized in the beachside photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa. But as we look to the past for lessons on the future, Vigreux argued, we would do well not to forget that the original Popular Front met a rather tragic end.

Over time, the Popular Front progressively lost the allegiance of the Radical Party. As the Spanish Civil War picked up steam, the alliance also tore itself apart over the question of French intervention. The Popular Front struggled to form a government, for the French right had become more aggressive following the strikes. As war with Germany loomed in the summer of 1939, it was common in upper-class circles to hear a preference for Hitler rather than any repeat of the Popular Front.

And so, when Germany invaded France in June 1940, Marshal Philippe Petain was granted full constitutional powers by a fragmented National Assembly. The Communist Party was soon outlawed and collaboration with the Nazis signed into law.

This, even more than the Action Francaise riots of 1934, was the true test of the French left. The far right was no longer outside Parliament but had come into power legally, with some votes tragically cast by members of the disbanded Popular Front. This episode has made the new iteration of the Popular Front particularly susceptible to criticism: Not only did it fail to curb the far right in the 1930s, the argument goes, but it handed it the keys to power.

The reality is, of course, more complex. By July 1940, the Popular Front had been out of power for more than two years. And though some politicians betrayed their 1935 oath, the majority did not participate in the vote, whether because they chose to abstain or because they were already sailing to North Africa, hoping to rekindle a French government in the colonies. And anyway, the original left-wing alliance was always about more than simply its politicians.

“The Popular Front of the 1930s was a political relay,” historian Danielle Tartakowsky told New Lines. It passed from the grassroots to the top, said the 76-year-old researcher, not the other way around. From February to June 1934, the “spring of committees” — an acceleration of civil society initiatives — gave the alliance a foothold among the French people. “This mobilization,” Tartakowsky explained, meant that the Popular Front could ultimately live on after its time in power, that it could “survive underground, in resistance movements across the country.”

Tartakowsky’s father was a journalist for L’Humanite. Her mother was a communist activist. During the war, they used their preexisting social networks to contact and join the underground resistance. Tartakowsky worries that the new iteration of the Popular Front lacks such a presence at the grassroots of French society.

Macron has thrown his grenade, and the French left is now at ground zero. The question, according to Tartakowsky, is not just whether the New Popular Front will get enough votes this Sunday but also whether the left can stay united beyond the election.

“We must make sure this alliance survives,” she concluded.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.