On April 21, 1928, Habiba Msika composed a letter in elaborate handwriting. “I would like to take this opportunity to thank you for the good electronic recording of my Arabic records,” wrote the singer, who was famous in North Africa and the Middle East for her subversive art and nonconformist lifestyle. “They are better than any I have recorded elsewhere and it is the first time I have heard my voice so clearly and naturally.” The young Jewish woman had traveled about 1,200 miles to create this sound — from her home in Tunis to the German city of Berlin, a cultural hub during the roaring ’20s.

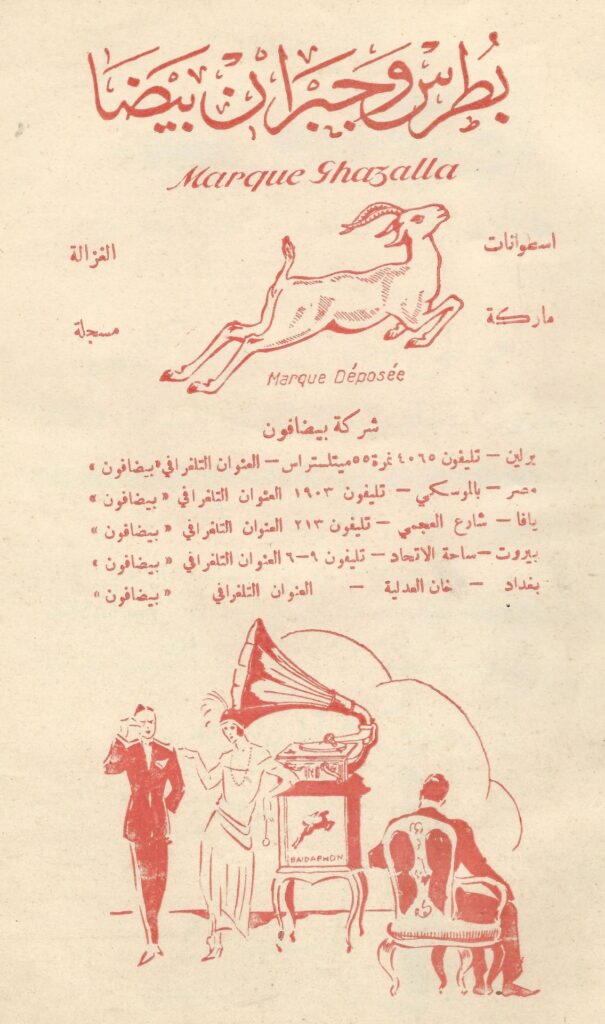

To this day, one of Msika’s recordings is stored in the Phonogramm-Archiv, a collection of recordings housed in Berlin’s upscale Dahlem neighborhood. Her music was pressed onto a black shellac record. The golden label reads “Baidaphon,” accompanied by the image of a leaping gazelle. It was the trademark of the record company to which Msika addressed her letter and which had its headquarters in the center of Berlin, near the Brandenburg Gate.

The Lebanese label produced hundreds, if not thousands, of recordings in Berlin up until the eve of World War II. Like Msika, many artists from North Africa and the Middle East were drawn to Berlin by state-of-the-art German recording technology. In some cases, Baidaphon recorded the musicians in their home countries, pressed the records in Berlin and sent them all over the world — from the New York diaspora to Tehran.

The records, distributed in Arabic, Farsi, Turkish and Hebrew, tell a story that has long been forgotten. The rise and fall of this music label is inextricably intertwined with the geopolitics of the 20th century. It is a story of entrepreneurship and inventiveness, spanning countries at a time of major global upheaval, and a story of love and friendship among Arabs and Jews at a time of growing racism and antisemitism. But above all, it is the story of the Baida family. A century after it began, this story has been reconstructed through old documents containing previously unknown information, the memories of living descendants and the immortal legacy of their music — an influence that has endured until today.

The story of Baidaphon begins in 19th-century Beirut. A man named Michel Baida was born there in the Mousaitbeh district in the mid-1880s. He grew up in a Christian family that worked in the construction industry. Together with his brothers Jibran and Boutros and some of their cousins — one of whom was a talented singer — Michel decided to found a music label. Gramophones had recently become popular, and this new industry was still dominated by companies based in Europe and the United States. The Baidas wanted to take Middle Eastern music production into their own hands, so they created the first Arab indie label.

Michel played a decisive role in this project. Not much is known about the early part of his life, but we do know that after studying medicine at St. Joseph University, he left Beirut and moved to imperial Germany, where modern sound technology was available. In 1912, a man by the name of “Dr. Michel Baida” from Berlin registered the company name “Baidaphon,” with the leaping gazelle as its logo, in the commercial register. His brothers Jibran and Boutros were soon listed in the Berlin address books as Gabriel and Pierre. It was the beginning of a flourishing family empire.

After World War I, the bankrupt Weimar Republic relied on investors to bring much-needed foreign currency into Germany. This enabled the Baidas to expand their interests rapidly: In addition to music, they invested their foreign money in a vast number of businesses, ranging from the wine and coal trades to Berlin real estate. They even became the commercial agents for the well-known German engineering company Bosch in Syria and Sicily. In the process, Michel made important contacts in political circles. In 1925, the German Foreign Office described him in a letter as “one of the wealthiest and most respected local oriental merchants.” Among his “local compatriots,” he enjoyed “the best reputation and has repeatedly rendered valuable services to the Foreign Office on the basis of his experience in the Orient.”

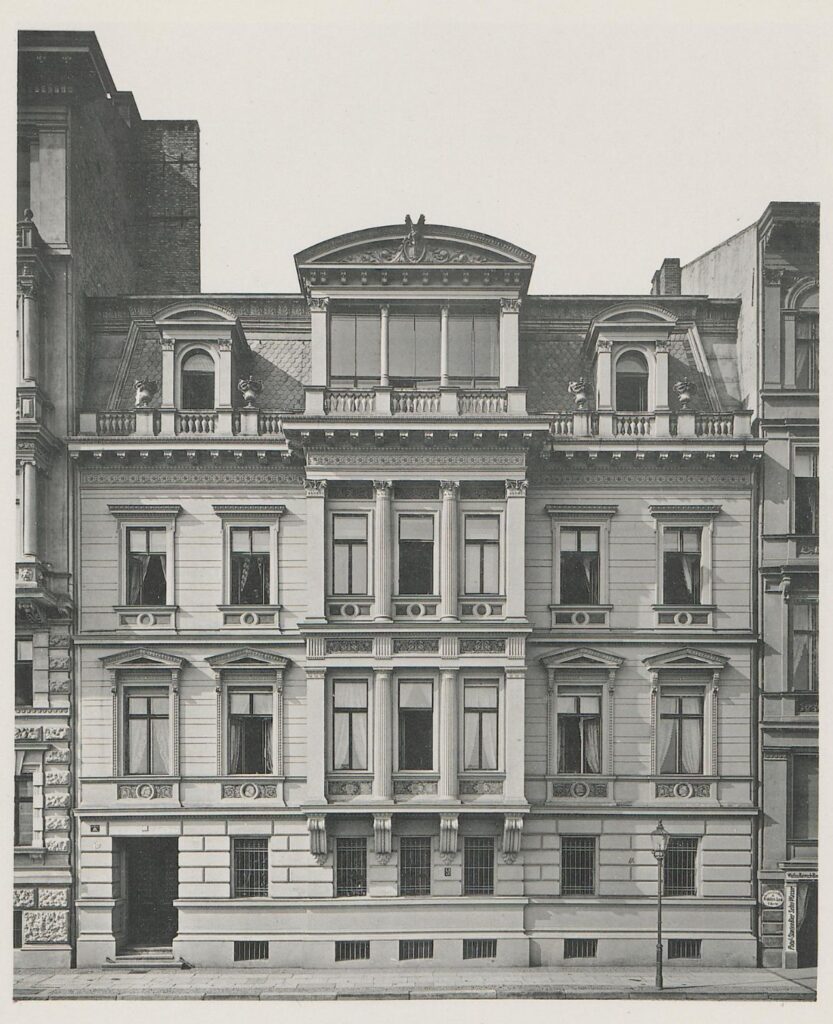

The Baidas’ wealth was reflected in their private lives. At Luetzowplatz, at the time a dazzling square in the neighborhood of Tiergarten in the western part of Berlin, Michel moved into the first floor of a four-story building. An old black-and-white photograph shows high windows and columns adorning the symmetrically elegant facade. There, Michel and his wife Hilde settled into seven rooms that cost 6,000 reichsmarks — Germany’s currency between 1925 and 1948 — in rent per year. That was considered a fortune compared to the average salary at the time, which ranged between 1,700 and 2,100 reichsmarks annually during the second half of the 1920s.

Born Eva Fanny Hildegard Casper in 1899, Hilde grew up in a German-Jewish family living in the very same neighborhood. Her father was a rentier, and her brother was a renowned lawyer who counted celebrities, such as the famous German writer Bertolt Brecht, among his clients. Hilde herself studied philosophy at Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin and later described her profession as “national economist.” In 1927, five years after getting married, the Baida couple paid 200,000 reichsmarks to have their apartment furnished by the Berlin luxury department store Gerson. They were probably preparing everything for the birth of the child that Hilde was carrying at the time. However, their son was stillborn, and the Baidas remained childless.

Despite this tragedy, Hilde and Michel led a carefree life in the Berlin of the roaring ’20s. “The conditions were more than positive. With my family, a prosperous business, a nice apartment,” Hilde later described in a letter. They did not know that their fortune would soon be tainted by political developments in Europe. But first, another political upheaval left an impression on their lives: the fight against colonialism in North Africa and the Middle East.

After the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, the colonial powers of Great Britain and France divided up large parts of North Africa and West Asia between them. It did not take long for resistance to form and for calls for self-determination to grow louder. The Germans, on the other hand, had no colonies in the region, so they were not seen as an enemy. Some Arab right-wing nationalists even went so far as to see the Germans, like themselves, as oppressed by the French and British.

“As a result, they perceived the strident nationalism of the German nationalists as proof of sympathy for their cause and they themselves as allies in the national liberation struggle,” reads a brochure on “Arabs in Berlin,” published in 2002 by Berlin’s commissioner for immigration. On the German side, solidarity groups formed “against the oppression of the colonized peoples.” At the same time, the Ministry of the Interior welcomed immigration as a step toward the necessary “reestablishment of spiritual relations with foreign countries.”

However, many German nationalists did not feel the same way on these issues of immigration or international solidarity with colonized peoples. Instead, supported by political parties and the media, they incited racism against Black people and Arabs, leading to attacks against these groups. Despite this atmosphere, Berlin became a magnet for the Arab-speaking diaspora between the world wars: Arab clubs hosted dance parties, and student associations and political groups organized demonstrations and published magazines.

This zeitgeist is reflected in Baidaphon’s records. Msika, for example, recorded a series of songs with nationalist lyrics during her stay in Berlin. “All of us! For the fatherland, for glory and the flag,” she sings in the oldest known recording of the Lebanese national anthem. “Not every record issued by Baidaphon was nationalist or anti-colonial,” historian Christopher Silver, from McGill University in Montreal, told us in a video call. “But many of the records were. And even if they weren’t, people interpreted them in a subversive way.”

During the 1930s, the French colonial authorities in Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco were so concerned about the influence of this music that they actually banned Baidaphon records in the territories under their control. They even accused Michel of acting on behalf of the Germans, with the aim of weakening French control over their colonies. Nevertheless, the music spread through relabeling and via the Baidaphon branches in Casablanca, Jaffa, Baghdad and Beirut.

It is unclear whether Michel and his brothers deliberately spread political ideas through their music or whether they saw it as a pure business opportunity. What is certain, however, is that Michel invited Shakib Arslan, one of the leading Arab nationalists of his time, to Berlin several times. At a lecture given by Arslan in Berlin in 1926, and hosted by Baida, around 70 Arab students and “other guests from the Orient” attended, as well as “several German nationalist members of parliament, a former general, several officers” and “a dozen ladies.” This was noted by an employee of the German Foreign Office, which was suspiciously observing the fraternization of German and Arab nationalists and opposition to the British and French.

After the Great Depression and with the rise of fascism in Europe, the atmosphere in Germany became more hostile toward the Baidas. At the beginning of the 1930s, Michel was accused of fraud and product piracy in connection with his coal trading and lighting technology businesses. Several of the Baidas’ properties were suddenly placed under receivership as payments remained outstanding. While it is quite possible that the Baidas used illicit methods in their business, the complainants’ letters suggest that growing racism and antisemitism also played a role. “They are real Orientals,” wrote the Standard Licht Gesellschaft, an electricity company, to the Federal Foreign Office in 1931. “What practices such people use, partly by blinding, bluffing, etc., is well known.” A tenant of one of the Baidas’ apartments wished that “this foreigner would be thoroughly stopped from deceiving and cheating Germans.”

In 1932, just a few steps from Michel’s and Hilde’s home, the Austrian who would soon cause the Baidas to leave Berlin was declared a German citizen at the legation of the former German Free State of Brunswick at Luetzowplatz: Adolf Hitler. His rise to power coincided with the climax of Baidaphon’s success. While Hitler became chancellor of the German Reich in 1933, the film “Al-Warda al-Baida” (“The White Rose”) was a box office hit in the Middle East. The leading role was played by well-known Egyptian singer Mohammed Abdel Wahab, one of the biggest stars of Baidaphon, which also distributed the film music for “Al-Warda al-Baida.”

“If Baidaphon had not existed, the world of Arab music would have been very different,” said Omar Khalil when we met him in the lobby of the Marriott Hotel in Zamalek, Cairo. Khalil is Abdel Wahab’s grandson and has his own music production business: “You never know what would have happened in history, but certainly the Arab music industry would have been more dominated by Western influence.” Egypt became part of Baidaphon’s stronghold, with Abdel Wahab later temporarily managing its subsidiary there, called Cairophon.

Michel and his wife Hilde did not have time to enjoy their success, however. The same year that thousands of people watched “Al-Warda al-Baida” in cinemas, the couple made a fateful decision: “The racist persecution caused me as a Jew and my husband as a member of the Arab-Semitic race to leave Berlin,” wrote Hilde after World War II, in a letter applying for compensation from Germany for the suffering inflicted on her.

Initially, Hilde fled to Paris without her husband “to wait and see how the events unfolded nearby.” Meanwhile, it seems that Michel tried to secure the Baidas’ assets and business in Berlin: In 1934, he had the Greek Orthodox archbishopric in Beirut issue him a letter in Arabic. “His family has always been known and belongs to the Greek Orthodox families who are very attached to the Christian faith and in whom there is no Jewish blood,” the archbishopric wrote about Michel. This document — which can only be understood as an Arabic equivalent of the German “Aryan Certificate” being issued under the Nazis at the time — was then translated by the German Consulate in Beirut, but to no avail.

Michel and Hilde spent five tense years between France, Egypt and Portugal, the last being where Hilde’s siblings had sought refuge. Finally, in 1938, the couple realized they could no longer see a future for themselves in Europe, as Hilde later wrote in her letter asking for compensation: “As a return to Berlin had become impossible, we decided to travel to Beyrouth together to put an end to the separations and the constant traveling back and forth.”

But even during that time, Michel managed to hire a new star for the label: Asmahan, the Druze princess from Syria who dedicated her short life to music. One of the rare surviving photos of Michel shows him with the blue-eyed singer, a white-haired man with friendly features and a fez on his head.

When Michel died in Beirut in July 1948, at the age of 64, some of his nephews and his wife Hilde carried on his musical recording and distribution legacy. Simultaneously, one of their relatives, Elia Baida, made a name for himself in the post-World War II United States as a talented singer and oud player.

To this day, a street in Beirut’s Mousaitbeh district is named after the talented Baida family, and there are relatives living across Lebanon who still remember the label’s founders, including Michel and his German-born wife Hilde, who became known in English and Arabic as Hilda.

“Hilda was ‘la lumière de la famille’ — the light of the family,” said Tania Baida, after inviting us into her small Beirut apartment. Tania is the grandniece of Michel and Hilde. The 80-year-old never worked in the record business herself. But the sleeves of some of the more recent Baidaphon records, which can still be bought in Beirut record stores today, bear her father’s name: Jean. He continued to run one part of the label after World War II; Hilde continued another. These records were pressed in Lebanon. Despite the early divorce from Jean, Tania’s mother was in close contact with Hilde and supported the widow financially. It seems that her demands for compensation from postwar Germany were only partially successful.

It’s hard to know, because Hilde hardly ever talked about her painful past in Germany during her grandnieces’ weekly visits, Tania recalled to New Lines over half a century later. Hilde had lost her German citizenship through her marriage to Michel, a foreigner, according to German law at the time, and became a Lebanese citizen following the independence of multiconfessional Lebanon in 1943. Never keeping her German-Jewish upbringing a secret, despite the continuous hostilities in the region following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Hilde continued living a life filled with arts and culture rather than religion, according to her grandniece: “Jewish, Christian, Muslim — none of that mattered to Hilde,” Tania said. She recalls that her grandaunt would often take her to cafes and teach her about the arts and jewelry, one of Hilde’s biggest passions.

But then, in the mid-1970s, she had to flee again. As the Lebanese civil war reduced large parts of Beirut to rubble, Hilde returned to Europe — to Portugal, where her sister still lived. Tania accompanied her on this last journey. “I still feel guilty today that I couldn’t do more for her,” she told us. Shortly afterward, in 1975, Hilde died in the Portuguese coastal town of Estoril.

Until the beginning of the 1990s, another of Michel’s nephews — Bernard Baida — continued to distribute the music of the old stars. Due to the civil war, he had the records pressed in Greece. After him, no one in the family continued to run the label with the leaping gazelle. Just recently, one of the young members of the Baida family and Khalil have started discussing plans to revive the label. But it could take some time until ownership rights and paperwork stretching over decades and countries can be recovered.

Until then, all that remains is the music that still plays in taxi radios across the region. And 100 years after the heyday of the Baidas, the German capital, with its 20th-century history of war, division and reinvention, has once again become home to a diverse North African and Middle Eastern diaspora, consisting of former revolutionaries of the Arab Spring, refugees-turned-citizens, students, scientists and migrants in search of economic prospects. With them, Baidaphon’s sound has returned to the city, playing in bars, clubs and restaurants only a few blocks away from where the records were once pressed and shipped off into the world. But there is another, more unfortunate parallel between Berlin today and in the 1930s. Racist and xenophobic tendencies are becoming widespread in German society and are once again becoming socially acceptable with the rise of the right-wing Alternative for Germany, or AfD, party. One can only hope that this trend does not lead to another expulsion of diverse cultures from Berlin, like the one that drove the Baidas and many others out of a city they called home.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.