Today, Damascus is no longer a safe place for globe-trotters, but once it was the jewel in the crown of Middle Eastern travel spots. “Damascus is simply an oasis, that is what it is,” wrote Mark Twain in his famous “The Innocents Abroad.” “So long as its waters remain to it away out there in the midst of that howling desert, so long will Damascus live to bless the sight of the tired and thirsty wayfarer.”

But even in its glorious days as a tourist destination, some places in the Syrian capital were too sensitive and secretive to appear in any atlas. One of them was George Haddad Street, which even today is unfindable on Google Maps. Had you turned into this small alleyway in the affluent Abu Rummaneh neighborhood during the 1980s and the 1990s, you might have detected an unusual presence of Syrian police officers, both uniformed and plain clothed, their eyes ever watchful. Tourists or expats who lingered for too long in George Haddad Street were occasionally stopped and asked about their business. Those who could not give a convincing answer were liable for quick arrest and deportation, if not worse.

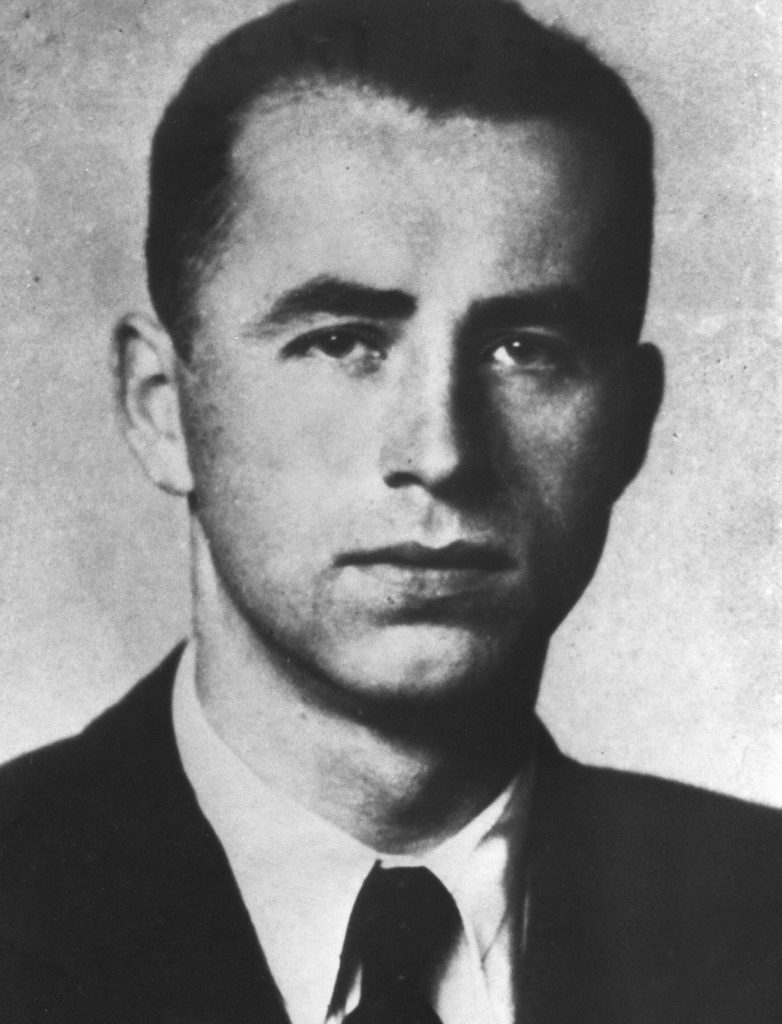

The security detail in the street watched especially one house, the corner building of George Haddad, number 22. This abode was, at least in the 1950s, Syrian government property with several apartments rented to low-ranking state guests, expats and foreign advisers. Some of them were Nazi war criminals on the run. Franz Stangl, the commandant of the Treblinka extermination camp, had lived there for a short while in the late 1940s. But the most famous “guest” in the building was Alois Brunner, one of the vilest Holocaust perpetrators then still at large. During the war, Brunner was a high-ranking Gestapo official, the No. 2 of Adolf Eichmann, head of the Gestapo’s “Department for Jewish Affairs.” Known as a trouble-shooter for extermination, Brunner and his closest associates personally oversaw the arrest, deportation and murder of tens of thousands of Jews in France, Slovakia, Greece and other countries. Eichmann, who was later tried and hanged in Jerusalem for his own role in the Holocaust, defined Brunner as his “best man.” After the war, Brunner hid for a short while in Germany, but in 1954 he felt the noose was tightening around his neck, especially when a French court sentenced him to death in absentia. With the help of Nazi friends he escaped to Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt. That began a Middle Eastern sojourn that ended only with his death half a century later.

Contrary to what a previous essay by a contributor of New Lines claimed, Brunner never served the Egyptian regime. In fact, he was deported from Cairo relatively quickly. Though Nasser employed several German experts in the fields of military and rocket science, as well as some propagandists and experts to domestic security, he had no need of genocide specialists. With the help of Amin al-Husseini, the former mufti of Jerusalem and a “guardian angel” of Nazis throughout the Middle East, Brunner escaped to Syria, received a work visa and joined the thriving scene of Nazi arms traders in Damascus in 1955. He entered the government property on 22 George Haddad St. as a sublease of a stiff German officer named Kurt Witzke, who worked as an adviser to the Syrian government. After a few years, Brunner denounced Witzke to Syrian intelligence, thus condemning his landlord to arrest and torture — all to have the entire apartment to himself.

The details on Brunner’s doings in Damascus during the 1950s are shrouded in mystery. Sensationalist accounts have since claimed that he managed the Damascene branch of an international Nazi underground led by Reichsleiter Martin Bormann (who perished in 1945) and Eichmann (who eked out a living as a manual laborer in Argentina until he was captured by Israel). More serious historians maintained that Brunner worked for the West German intelligence service (BND) as an agent or even as their resident in Damascus. At first glance, these claims are supported by circumstantial evidence. We know that the BND did not hesitate to employ Nazis, including Holocaust perpetrators, many of whom were tucked in faraway countries well away from prying eyes. Then, we also know that Brunner’s 750-page BND file was shredded in the 1990s, probably under orders from the highest echelons in Berlin. The destruction of the file raises a suspicion that the German government had something serious to hide.

However, some other evidence shows that Brunner was probably not a West German spy. The documents of the West German Consulate in Damascus prove that “Dr. Georg Fischer” (Brunner’s pseudonym) avoided any contact with the consulate, except an odd denunciation letter against rivals in the local German community. Though he may have given pieces of information to the BND here and there, it is hard to believe that he was an agent or a resident without anyone in the consulate knowing about it. Other Nazis in Damascus did work for the BND, and their files do not contain any evidence that Brunner was recruited as well.

What we do know of Brunner’s work in Damascus is no less interesting, however. He bonded with fellow Nazi fugitives, most importantly Franz Rademacher, the former “expert for Jewish affairs” of the Nazi Foreign Office, and Dr. Wilhelm Beisner, a notorious SD spy who was supposed to exterminate the Jews of Palestine after Germany’s victory, in co-founding a company named OTRACO (Orient Trading Company). Along with other faux companies in Germany and other countries, mostly managed by Nazis and neo-Nazis, OTRACO was a front for a highly profitable business of arms smuggling from the Eastern bloc to the Algerian underground, the National Liberation Front (FLN) in its war of liberation against French colonial rule.

In the beginning of the Algerian War, the Soviet Union was reluctant to support the FLN openly, so it managed its support indirectly through intermediaries, some of them former Nazis. Brunner enriched himself greatly in this business, but in 1959 his luck was about to run out. Unbeknownst to him, Syrian intelligence agents were watching his activity — and they were not happy about it.

In 1958, while Brunner was trading in arms, Nasser’s Egypt swallowed Syria, and the two countries merged into the United Arab Republic (UAR). In Syria, known as the northern province of the UAR, there were at least three intelligence agencies, the wildest and most notorious of which was known as the “Special Bureau” (Al Maktab Al Khas). Established by Abdel Hamid Sarraj, the strongman of the northern province, it was designed as an omnipotent entity empowered to oversee the other security services. One of the Special Bureau’s leaders, a shady type known to us only as “Captain Laham,” held a number of abandoned villas and other structures in the suburbs of Damascus. Inside, prisoners were held for “special treatment.” The interrogators, mostly Palestinian refugees, were cruel and eager to please their Syrian superiors.

On an unknown date in late 1959, Brunner was arrested and brought into one of these facilities. Laham, who probably suspected Brunner’s international transactions and believed he was a spy, accused him of drug smuggling and ordered him arrested “until the end of the investigation.” Knowing full well that he may not get out of the facility alive, Brunner tried his last card. “I was Eichmann’s assistant,” he told Laham, “and I’m hunted because I’m an enemy of the Jews.” Laham’s attitude suddenly changed. He rose up and shook Brunner’s hand. “Welcome to Syria,” he beamed. “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

From that day, Brunner became an adviser for German affairs in Syrian intelligence. With Laham’s blessing, he recruited several of his Nazi friends, including Rademacher. Their Syrian counterparts, Laham and Col. Mamduh al-Midani, were German-speaking Syrians who sympathized with Hitler’s regime and served the Third Reich during World War II. Together they collected intelligence on Germans and Austrians who lived in Syria and smuggled weapons to the FLN, snatching hefty commissions in the process. Hermann Schaefer, a journalist and amateur detective who collected intelligence on the Nazi fugitives in Syria, later shared a cynical anecdote: Whenever an extradition request from West Germany arrived at the Special Office, Midani summoned Brunner and Rademacher to his desk and asked them “whether they live in Syria.” When they replied in the negative, hardly suppressing their laugh, Midani answered West Germany in the name of the Home Ministry that “there are no such persons in the United Arab Republic.”

At the same time, Brunner served Syrian intelligence as an instructor of Nazi torture and interrogation techniques. Every day he traveled to Wadi Barada, a neighborhood on the outskirts of Damascus, where he initiated Syrian officers into Gestapo methods and taught them to speak German “in the charming Viennese accent.” Some notorious future leaders of Syrian intelligence, such as Gen. Ali Duba (the commander of the military security service, Syria’s most powerful intelligence agency from 1973 to 2000), were presumably Brunner’s students. There are commentators who even ascribe to Brunner the invention of the so-called German Chair, a torture device too gruesome to be described here, though this was never sufficiently proven.

And yet, in 1960, Brunner had bigger ambitions than working as an instructor. His mind increasingly turned to Eichmann, his former boss, who was kidnapped by the Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency, and brought to trial in Israel. “Eichmann was dear to me,” he said, and submitted a special request to Laham. “Would it be possible,” Brunner asked, “to snitch Eichmann from Zionist captivity by means of a daring commando raid?” Brunner’s request was politely declined.

But the fugitive Nazi did not despair, as yet. He tried to recruit a group of Arab and Austrian adventurers and pay them to kidnap Dr. Nahum Goldmann, the president of the World Jewish Congress, and take him to the Algerian FLN to be exchanged for Eichmann. This far-fetched plan also crumbled when the Nazi commando veterans who should have spearheaded the operation starkly refused to take part, and one of them even leaked the plan to the Jewish Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. It is funny, however, how much Brunner was ignorant about Jewish affairs. Beholden with Nazi illusions on “Jewish world power,” he failed to realize that by 1960 Goldmann was unloved in Israel, and no one would have even considered trading him for Eichmann. Back then, many Israelis perceived the president of the World Jewish Congress as a scheming politician, too conciliatory toward the Arab world and altogether too rich. One Mossad veteran whom I interviewed told me mockingly: “Shame that he didn’t tell us he wanted to kidnap Goldmann. We would have helped him.”

What Brunner did not realize is that, like two years beforehand, a hostile intelligence service was watching him from the shadows, but this time with no intention to recruit him. Seething with desire for revenge for the Holocaust, Mossad operatives were following Brunner in the heart of the Syrian capital with deadly intent.

Dr. Fritz Bauer, a German-Jewish prosecutor and Nazi hunter, had already shared Brunner’s whereabouts with the Mossad by the summer of 1960. Shortly after, Tel Aviv received another tip from Franz Peter Kubainski, a dubious neo-Nazi who converted to Islam and worked as an intelligence peddler in the Arab world. Juxtaposing these and other available sources, the Mossad learned that Brunner lived on the third floor of 22 George Haddad St. under the false name “Georg Fischer.”

The news on Brunner’s hideout in Syria reached the Mossad with perfect timing. As recently as 1958, this might well have been ignored. During the 1950s, Isser Harel’s Mossad was indifferent to Nazi hunting, preferring instead to invest its efforts in fighting the enemies of the present. Only a wave of antisemitic incidents that spread over the entire world in 1959, as well as pressure from the highly respected Bauer, changed Harel’s priorities, fueling the dynamics that led to Eichmann’s abduction in 1960. Concurrently, the Mossad was also hunting for Josef Mengele, the sadistic physician from the Auschwitz extermination camp. The enormous public impact of the Eichmann trial, along with convincing intelligence on Brunner’s whereabouts, tempted Harel to catch Eichmann’s right-hand man, who seemed to be easy prey.

Very quickly, however, the Mossad decided that it was too difficult to abduct Brunner from Damascus. The plans to bring him to trial were thus scrapped, replaced with a scheme of assassination (or in the parlance of the Mossad: “a punitive attack”). Harel gave the mission to a small unit named “Mifratz” (“Gulf”) that specialized in clandestine ops, especially in Arab countries. Future Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, who headed the unit back then, filled it with his comrades from the extremist Jewish underground “Lehi,” all of whom had rich experience in assassination operations during the clandestine war for Israel’s establishment prior to 1948.

Shamir chose for the mission one Lehi veteran, a native Arabic speaker known to us only by his first name “Ner.” This experienced assassin reached Damascus first in May 1961, during Eid al Adha, exploiting the Muslim holiday’s hustle and bustle to secretly spy on Brunner. Reaching 22 George Haddad St., which was then unguarded, he climbed the stairs and knocked on Brunner’s door, telling the suspicious European that he was looking for one “Mr. Tabara.” Brunner, dressed in a bathrobe, mumbled something and closed the door. Facing an arch enemy of the Jewish people in close quarters, Ner decided against killing him on the spot because his orders were only to collect intelligence and he did not have an escape route. On his second visit to Damascus in September that year, he was equipped with a parcel bomb. But instead of giving the parcel to Brunner personally or leaving it outside his door, Ner made the crucial mistake of sending the bomb by mail.

Brunner took the precaution of opening the parcel with a long tool — a move that probably saved his life. A few days later, Shamir and his boss Harel read in the Arab press that a “foreigner was wounded in Damascus’ main post office.” A senior UAR intelligence officer told an Israeli source that the victim of the explosion was a man named Georg Fischer “with a past of activity against the Jews.” Having realized their failure, Shamir and his fellow Mossad commanders left Brunner alone. Only after two decades would they try to kill him again.

Brunner lost one of his eyes in the parcel attack. While convalescing in a heavily guarded hospital room, his luck threatened to betray him again, this time because of the stormy developments in Syrian politics. On Sept. 28, 1961, the residents of Damascus woke up to the familiar sounds of military trucks and armored columns: an anti-Egyptian coup d’etat. The “High Arab Revolutionary Command” soon came on the radio and declared full disengagement from Cairo. Though Nasser was highly popular in Syria, many citizens of the northern province cherished their Syrian identity and resented the waves of Egyptian police officers and bureaucrats dispatched from Cairo to micromanage all aspects of their life and work. Therefore, the coup was at least tolerated, if not supported, by most influential circles in Damascus. The new regime deported all Egyptian “guests” and arrested many of their Syrian accomplices, including the all-powerful chief of intelligence and Brunner’s patron Sarraj.

As is usual after coups, foreign proteges of the previous regime were targeted by the new rulers in Damascus. As the interim government released political prisoners and abolished Sarraj’s hated apparatus of terror, its spokesperson directed especially strident criticism toward the UAR’s “German mercenaries.” Lying in his hospital bed, Brunner was horrified to read in the Syrian and Lebanese press that “the previous regime established a merciless police state, with spies and torturers trained by Nazi experts.” President Maamun al-Kuzbari’s new administration promised to publish all details in a soon-to-appear “black book.” Meanwhile, from his office in Frankfurt, the tireless Bauer realized the opportunity, and formally asked the new regime to extradite Brunner. The West German consul in Damascus, however, was not optimistic. He warned the prosecutor that no Syrian regime, even the relatively liberal government of Kuzbari, would dare to extradite a person deemed “an enemy of Israel.”

The consul was right. Damascus never thought of extraditing Brunner, though some testimonies show that the new regime did consider, for a while, to try and jail him for his crimes against the Syrian people. However, the Nazi fugitive was saved, yet again, by the game of thrones in the Damascene intelligence community. Though Sarraj and Midani lost their career and influence, Brunner’s direct patron, Laham, was able to find a lucrative job in the newly formed military intelligence service in return for denouncing “the crimes of Sarraj and his Egyptian patrons.” He convinced the new leaders in Damascus that Brunner could also serve as an excellent witness against the previous regime. As the U.S. Consulate in Damascus predicted, the black book on Brunner’s crimes was never published. There were many secrets that the new regime, too, preferred to bury in the dark.

As the years passed, Brunner resumed his old job as an intelligence agent and torture instructor as if nothing had happened. His status rose even higher when the relatively “liberal,” post-coup regime was replaced by a succession of increasingly authoritarian Baath governments. A series of Baath leaders, from Amin al-Hafiz and Salah Jadid to Hafez al-Assad, “spoiled” Brunner with high salaries and benefits reserved for special proteges of the regime. In the 1960s he enjoyed a car with a driver, luxurious trips throughout Syria and visits from numerous regime bigwigs.

Israel, too, forgot about Brunner. In the late 1960s, Levi Eshkol’s government decided to forego operations of Nazi hunting, as “the Eichmann Trial is sufficient as a symbol.” The country had enough trouble already and needed no further international complications. In these years, information on Nazis was deemed so unimportant that briefs on that subject were stuck for months in folders before reaching their addressees. In one case, it took two Mossad offices several months to exchange one piece of information on Brunner, though they were only 100 yards apart.

Briefly, in 1977, Brunner appeared again on the Israeli radar, when the Labor Party government lost the elections and was replaced with a right-wing administration led by Menachem Begin’s Likud. Begin cared deeply for the Holocaust, in which his entire family perished, and as a result ordered the Mossad to reinitiate Nazi hunting, bringing the most important remaining criminals to justice, “abducting them, and if that proves impossible — killing them.”

Yitzhak Hofi, the head of the Mossad, was unenthusiastic but obedient. He sent several agents to Damascus to sniff for Brunner’s whereabouts. The most colorful of them was a Muslim Bosnian nationalist known by the pseudonym “Stiff,” who befriended Brunner and visited his house on George Haddad Street. He duly dispatched to Tel Aviv a map of the premises. However, unlike in 1961, the head of the Mossad’s operational unit decided it was too dangerous to send agents to kill Brunner. He preferred the safer strategy of dispatching a letter bomb by mail. Stiff told the Mossad that Brunner, now a strict vegetarian, was a subscriber to an Austrian magazine on natural medicine. Hofi’s assassins used this fact to trick Brunner and send him a letter bomb disguised as a special issue of the magazine. But yet again, the amount of explosives was too small. When Brunner opened the envelope in his apartment, he lost several fingers in the explosion but remained alive. His blood, however, soaked the wooden floor of the apartment. No one was ever able to clean it up.

Finally, Brunner was punished not by Israel, but by the Syrian regime whom he served for so long. During the 1980s and 1990s the regime in Damascus kept on protecting him, answering numerous extradition requests from Austria, West Germany and the United States with the repetitive reply that “no such person exists in Syria.” And yet, following the highly effectual media campaigns of the Nazi hunters Serge and Beate Klarsfled against Brunner, the regime became embarrassed by his presence in the capital. After all, he had long outlived his usefulness. Now we know, based on testimonies of Brunner’s guards to Hedi Aouidj, a French investigative journalist, that the regime in Damascus had increasingly limited Brunner’s movements throughout the 1980s and 1990s, especially after he violated Assad’s direct instructions to keep a low profile by giving repeated interviews to the German, Austrian and international media.

Assad had finally decided to get rid of Brunner in 1996, ordering him removed from his apartment and jailed indefinitely in an underground cell below the Muhajirun Police Station. “The door was closed,” testified one of the guards, “and never opened again.” Brunner spent his final years in misery and squalor. “Don’t kill this pig, but don’t try to keep him alive as well,” one Syrian commander instructed the jailers. In interviews to Aouidj, Brunner’s guards disclosed that to humiliate him, he had to choose every day between a hard-boiled egg and a tomato, “either of the two.” The guards recalled that he often cursed them, moaned and yelled, but sometimes stopped in order to “give them advice about their health.” Brunner, now elderly and sick, eventually died after 2001, though exactly when is a matter of some dispute. His body was removed from the cell and secretly buried in a Muslim cemetery. Finally, Brunner’s life ended in worse conditions than any Western country would have given him, and yet, far better than the suffering he forced on his numerous Jewish victims.