Latin America lost one of its leading intellectual figures in December 2024, when the Argentine writer and critic Beatriz Sarlo passed away in Buenos Aires at the age of 82. Over the course of a decades-long career, she wrote about nearly every major cultural and political issue of her time: from Argentine literature and the role of memory in the aftermath of dictatorship to the changes wrought by globalization and postmodernism. She transcended the narrow confines of literary criticism and academic life, directing a leading cultural magazine, helping to shape the canon of contemporary Argentine fiction and featuring regularly on radio and television. In recent years, she even appeared on popular podcasts in her native country.

Sarlo’s output is marked not only by the rigor of her thinking but also by her public interventions and her radical mistrust of the prevailing consensus. She was strongly attached to Argentina, yet rarely aligned with the intellectual confines that such an attachment might have implied. Deeply shaped by leftist ideas, she often found herself at odds with other leftists. Her legacy stands as a testament to public debate and independence of thought.

One chapter in her life underscores her fierce independence and complicated relationship with the Argentine left. On April 2, 1982, Argentina — under military dictatorship — invaded the Falkland Islands (also known as Islas Malvinas) and declared them a sovereign Argentine territory. Located in the South Atlantic Ocean, about 300 miles east of Argentine Patagonia, this archipelago has a harsh, windy climate, with average summer temperatures barely reaching 46 degrees Fahrenheit. Argentina had long claimed the islands, which Britain had occupied since 1833. In 1965, the United Nations passed a resolution urging both countries to engage in negotiations to find a peaceful solution, but little progress had been made. In Argentina, public opinion overwhelmingly supported the country’s claim. The islands were seen as a symbol of colonialism and a rightful part of the national territory.

Following the invasion, Argentina was swept by a wave of nationalist fervor. Popular support for the military’s decision was virtually unanimous. Thousands gathered in Plaza de Mayo, Buenos Aires’ central square, to celebrate the move, and nearly every major institution voiced its approval. The conflict played on deep currents of nationalistic and anti-imperialist sentiment in Argentine society.

Sarlo, however, took a marginal position: She opposed the war outright. She believed that the invasion of the islands was simply a political maneuver by the military junta to preserve its hold on power. International opinion had turned against the Argentine regime over its human rights violations, the country was suffering an economic crisis and tensions within the armed forces were mounting. Increasingly isolated and losing popular support, the dictatorship needed a unifying cause; a war, Sarlo believed, was the perfect lifeline to obtain legitimacy.

Her stance was controversial, even among fellow intellectuals. For many on the Argentine left, the dictatorship was illegitimate, but so, too, was Britain’s claim to the islands. The islands were a residue of imperial occupation, and the war — even if initiated by a vicious regime — could be framed as a legitimate “lucha popular” (people’s struggle).

Sarlo rejected this logic. She maintained that the war could not be considered outside its domestic context or the interests that fueled it. More troubling was the fact that the country seemed to have descended into a blind nationalism with little space for careful moral reflection. “I never felt so distanced from the country I lived in as during those months,” she later wrote. “That collective fantasy was my nightmare.”

The controversy followed her for decades. In 2013, she traveled to the Falklands to cover the referendum in which the islanders — about 44% of whom, according to a 2021 census, were born on the islands, while 55% had migrated from elsewhere, primarily the U.K., followed by countries like Chile and the island of Saint Helena — would decide whether to remain as a British Overseas Territory (99% of the 1,518 voters said yes, with only three votes against). Her chronicle, published in the Argentine newspaper La Nacion and later included in a collection of her travel writings, was an account of how distant and foreign the islands felt. Through conversations with locals and the observations of their daily life, she described the islanders’ distrust of Argentines, whom they still saw as the “invaders.” Sarlo also expressed sympathy for their desire for self-determination — a position she reached, paradoxically, through her own experience under a dictatorship. No people, she argued, should be forced to live under a government they reject. Back in Argentina, her stance — an uncompromisingly honest one that deviated from the dominant nationalist line — once again sparked condemnation. She was branded a “vendepatria,” which literally means someone who sells out the homeland — that is to say, a traitor.

In her later years, Sarlo’s political views were hotly debated — and attacked. Particularly contentious was her outspoken opposition to Kirchnerism, the political movement associated with the ideology and policies of former presidents Nestor Kirchner (2003-2007) and his wife, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner (2007-2015). Kirchnerism sprouted from Peronism, the popular, difficult-to-classify movement founded by Juan Domingo Peron — who served as president three times, in 1946, 1952 and 1973 — and leaned toward a left-wing populism centered on state intervention, social spending and opposition to neoliberalism. Naturally, Sarlo’s critical stance drew the ire of leftist intellectuals aligned with Kirchnerism. Despite her Marxist past and her principled opposition to the dictatorship, she was now accused of having drifted into bourgeois complacency, becoming little more than a tepid liberal. Worse still, her critics said, her attacks — published in articles for media outlets seen as sympathetic to the right — seemed to lend credibility to the right’s political project.

Sarlo never aligned herself with the right or with Macrism, the movement associated with former president Mauricio Macri (2015-2019). She remained consistently critical of right-wing policies and even supported the (unsuccessful) presidential candidacy of Argentina’s Socialist Party in 2011. Still, her critiques placed her in an ambiguous position that did not fit easily within Argentina’s sharply polarized political landscape.

For Sarlo, Kirchnerism itself had engineered this polarization, particularly through its use of state media and divisive rhetoric. Anyone not unambiguously aligned with the movement, she noted, was labeled an enemy of the people or a pawn of the right-wing propaganda machine. She was also skeptical of what she considered the performative character of Kirchnerist politics: the Kirchners’ overt theatricality and their instrumentalization of human rights discourse, using it as a shield to place themselves above criticism. Behind these gestures, she believed, there were not moral convictions but hypocrisy, the most virulently authoritarian tendencies concealed under a progressive coating.

In 2011, a collection of Sarlo’s essays on Kirchnerism was published. That same year, she appeared on “6, 7, 8” — a pro-Kirchnerist television program where a group of panelists would offer critical commentary on opposition media and dissenting voices. One of the panelists, the Argentine journalist Orlando Barone, accused Sarlo of losing her moral compass by writing for Clarin and La Nacion, two major newspapers hostile to Kirchnerism and frequently accused of serving right-wing interests. Sarlo fired back: “Conmigo no, Barone,” she said, which could be roughly translated as “Don’t mess with me, Barone.” With that phrase, she reminded the panelist that he too had worked for La Nacion, but also reaffirmed her intellectual independence. She was not a mouthpiece parroting the party line, but an intellectual doing her duty. The phrase “Conmigo no” went viral and established Sarlo as a prominent figure in Argentina.

Sarlo died just a few weeks before the publication of her final book, a memoir titled “No Entender” (“Not Understanding”). At first glance, the choice of this title seems nothing short of puzzling. Sarlo’s role as a critic and intellectual was precisely concerned with understanding: apprehending what often passes unnoticed or misunderstood and swimming against the tide of conventional wisdom to gain a sharper, more incisive perspective. Good critics, as Sarlo knew, do not necessarily assert taste; they reconstruct the reasoning behind their aesthetic, cultural or political judgements. Their goal is not simply to persuade, but to invite the reader into their thought process, showing how and why one should pay attention to particular aspects of works of art. Criticism offers, in many ways, a training in attention.

Yet Sarlo’s memoir makes the case that not understanding — in literature, politics or everyday life — constitutes a critic’s defining experience. To not understand is to glimpse the promise of a future revelation, one that attention, reading and analysis may eventually bring forth. To not understand functions as a guiding mechanism, a kind of critical compass: anything too straightforward, too self-evident, may not be worth one’s time.

Not understanding also underscores something essential about all great works: There is always a remainder, a residue of meaning that resists full interpretation. Finally, not understanding offers a way to marvel at one’s mind: In the effort of making sense of what eludes us, we witness the passage from obscurity to clarity, from ignorance to comprehension. The miracle of human intelligence makes itself visible. “I started not understanding,” writes Sarlo, “but almost instantly I accepted it as the entry point to anything worthwhile.”

So if we are to understand (and perhaps not understand) Sarlo’s significance as a Latin American intellectual, we might begin by considering a few key moments from her incredibly productive, dauntingly protean career, tracing how she responded to the demands posed by history.

The military dictatorship that ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983 played a central role in Sarlo’s trajectory. Led by Gen. Jorge Rafael Videla, the military regime overthrew the government of Maria Estela Martinez de Peron in March and soon unleashed an unprecedented campaign of state terror. In the years that followed, systematic torture, abductions, arrests and extrajudicial executions became rampant. Pregnant women were forced to give birth while imprisoned; their children were confiscated and placed with families loyal to the dictatorship, who never disclosed the babies’ real origins. Most victims’ bodies were never recovered, buried in unmarked graves or thrown into the sea. These “disappeared” would become the symbol of the era’s horror, sparking human rights movements that would shape Argentina’s political and cultural life for decades.

Human rights groups estimate that more than 30,000 people were murdered and disappeared during those years (this figure has been recently disputed by Argentina’s current president, Javier Milei, who claims there were 8,753). The targets of the state’s systematic violence were not only armed Marxist revolutionary groups but also social and political organizations, union leaders, activists, intellectuals, university students and essentially anyone suspected of leftist sympathies or opposing the regime. Labor unions were prohibited, most political parties disbanded and the press silenced under strict censorship. A thick cloud of silence, paranoia and complicity settled over the country.

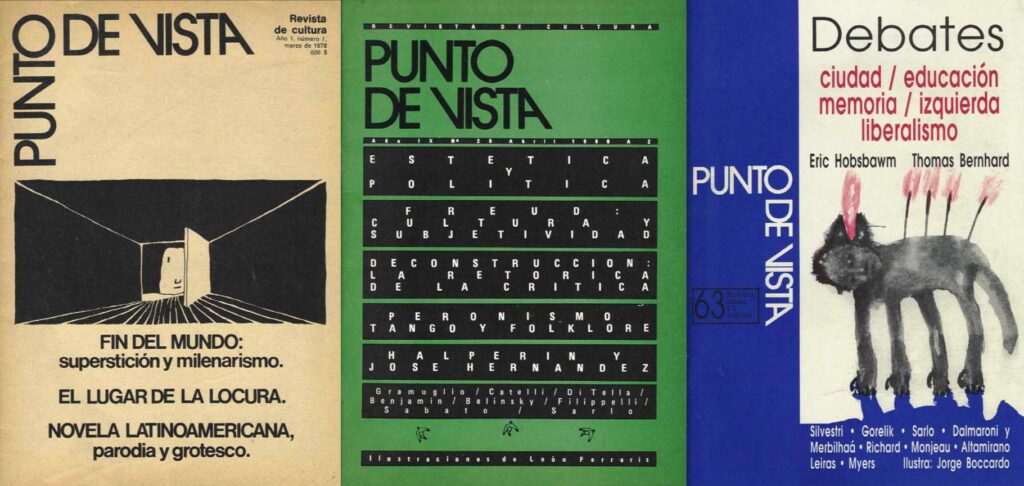

Sarlo, then in her early 30s, made a decision that carried real personal danger: Together with Carlos Altamirano and the novelist Ricardo Piglia, she founded Punto de Vista (Point of View), a small cultural magazine that would become a touchstone of Argentina’s intellectual life. Its first issue was published in 1978 with no masthead, at the height of the dictatorship’s reign of terror, defying its climate of censorship and fear. Barely launched, the project nearly collapsed after two Maoist intellectuals who had financed its first two issues were abducted and disappeared. Yet Sarlo and her co-editors resolved to keep on with the project. The magazine endured for more than three decades, publishing continuously until 2008, when it closed under Sarlo’s editorship.

Sarlo’s choice to stay in Argentina and publish within the dictatorship’s shadow already reveals something important about her intellectual identity. For many writers and thinkers, the dictatorship posed an impossible choice: to leave the country and live in exile, or to remain and try to work from within. The tension had been building up in the decades before the coup, as leftists debated whether meaningful political work could be done from abroad. But after 1976, the question became unavoidable.

Heated debates emerged in the wake of the dictatorship, pitting those who left (like Julio Cortazar, author of the celebrated novel “Hopscotch”) against those who stayed (like the writer Liliana Heker). For some, resistance was futile in a country where censorship ruled and independent thought was nearly impossible. For others, staying and writing under these conditions was the last line of defense in the struggle for intellectual freedom. The debate extended to literature itself: Were the most original and vital Argentine works being written at home or abroad?

Sarlo chose to stay in Buenos Aires, the only place, she later said, where she could “recognize herself as an intellectual.” This commitment to Argentina defined her work. Unlike other Latin American thinkers of comparable stature, Sarlo did not position the continent at the heart of her intellectual project. In this way she differed, for example, from the Uruguayan (and equally influential) literary critic Angel Rama, who made a point of examining how Latin American popular and rural worldviews merged with Western cultural forms through processes of modernization and cultural negotiation. Rama’s studies of how certain Latin American novelists incorporated elements of Indigenous and oral traditions into their fiction were momentous in shaping the region’s literary debates.

Sarlo, by contrast, was not so much interested in Latin America as an idea or a question in itself. She certainly engaged in debates with other Latin American intellectuals and even published a collection of travel chronicles from her journeys through the region, but time and again her curiosity turned back to Argentina’s politics, literature and culture. In her memoir, she articulates her identity in a strict hierarchy: first Argentine, then from Buenos Aires and only third — and reluctantly — Latin American. It is only at this final remove, she writes, that she accepts “the adjective that placed me on the continent.”

But even as she wrote obsessively, almost parochially, about Argentina, Sarlo’s way of thinking rarely aligned with the local worldview. Quite the opposite: Through Punto de Vista and the essays she published there, she introduced Argentine readers to critical methods and philosophical currents that had barely been explored in the country.

A prime example of this was her engagement with the work of the British writer Raymond Williams, whose books “The Long Revolution” (1961) and “Marxism and Literature” (1977) she helped find an Argentine audience. Williams offered Sarlo an alternative to the dominant critical framework of the time — French structuralism — which had shaped literary criticism in the region throughout the 1960s and 1970s. But just as the dictatorship seized power, Sarlo began to distance herself from that framework. Structuralism, at its most reductive, approached culture as the surface expression through which material (political and economic) forces operate. Sarlo found in Williams a model for understanding culture as an active terrain of struggle, where literary criticism could function as a form of political intervention.

Sarlo’s engagement with structuralism and the work of Williams was part of the evolution of her thinking, but it also underscores her contribution to Argentina’s intellectual life. Both as an editor and as a critic, she made a deliberate effort to disseminate new ways of reading and interpreting literature, introducing little-known theoretical frameworks into the Latin American context. What she did with Williams, she also did with others (the American cultural historian Carl Schorske and the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, for example), helping to bring their work to new readers. This was no small task, considering that she was working under the shadow of the dictatorship, Punto de Vista initially had limited circulation and access to translations was scarce.

Beneath these efforts, Sarlo expressed a vehement desire to dismantle — by any means necessary — entrenched and habitual ways of thinking about culture. Sarlo was especially unsympathetic to any form of critical stagnation. She cringed when certain authors, even those she admired, became trapped in simplistic, recycled interpretations, repeated in academic circles until they had lost their vitality. The Argentine novelist and critic Martin Kohan tells a story that captures this well. In the 1990s, during an oral exam at the University of Buenos Aires (where Sarlo was a professor of Argentine literature), a student confidently recited the postmodern mantras then in vogue: There is no “true” reality; everything is fiction; mass media’s images and codes shape our entire perception of the world. Sarlo listened carefully, then interrupted: “Tell me,” she asked the student, “do you really believe that?”

The same desire to liberate texts from stale readings was the guiding impulse behind many of her books. In “Jorge Luis Borges: A Writer on the Edge” (1993), Sarlo endeavored to counter the dominant image of the Argentine master as a purely cosmopolitan figure. Sarlo argued that, as Borges became a global literary icon, commentary on him increasingly effaced his local roots and instead focused on his vast erudition, his immersion in English literature and Nordic sagas, his obsession with abstract philosophical questions, and his recursive use of labyrinths, myths and puzzles. The literary world painted him as the emblem of universalism. Sarlo didn’t fully reject this reading but instead argued that it obscured Borges’ profound connection to Argentina. She didn’t want to provincialize Borges, but to put his work back into dialogue with the local texts, history and landscapes that so thoroughly shaped it. “There is no writer in Argentine literature who is more Argentine than Borges,” she wrote.

A few years later, in 2000, Sarlo turned her critical gaze from the literary establishment to the academic world. That year, she published a collection of essays on the German-Jewish philosopher and literary critic Walter Benjamin, who explored how technology and capitalism transformed not only art but also everyday experience, and whose work is ubiquitous in humanities departments across the globe.

Sarlo was a devoted reader of Benjamin; not only was she deeply familiar with his biography, but his ideas had greatly shaped some of her previous books. Yet she felt that Benjamin had become overused in academic circles. Tellingly, she closed the volume with an essay titled “Forgetting Benjamin,” where she criticized the “canonization” of a thinker whose ideas had been sanitized, their theoretical power hollowed out. Playing on the term “politically correct,” she called out the “academically correct”: the automatic deployment of canonical quotes and the rote invocation of respectable themes (“identity formation,” “the city,” “political discourse”) without seriously asking why these topics deserve attention. Benjamin, Sarlo insisted, was not a jack-of-all-trades. His ideas cannot, and should not, be applied indiscriminately, summoned at every corner to imbue texts with a halo of critical respectability. We needed to “forget” Benjamin in order to confront the contradictions and radical possibilities of his work.

Perhaps like any “great” thinker, a portrait of Sarlo necessarily traces a broader intellectual history. As a university student and during her first few years working as an editor, she was deeply steeped in Marxist ideas. She then moved through what was then in vogue: structuralism, Russian formalism, the theories of Althusser and Foucault, followed by her turn to Williams and the British New Left. She wrote several books on Argentine fiction, devoting essays to emerging authors while also contributing to the canonization of relatively unknown figures like the fiction writer Juan Jose Saer. The range of her interests is difficult to match in this age. Too often, intellectuals get lost in narrow specialization or, at another extreme, embrace a vague eclecticism that obscures the methodological framework and guiding values behind their ideas. Sarlo did neither.

It is difficult to assess Sarlo’s legacy without mindlessly repeating the very platitudes she herself would have condemned. Practically everything that can be attributed to the figure of “the intellectual” applies to her: independence, breadth, erudition, critical sharpness, popularity, eclecticism, an uncompromising spirit that is not afraid of controversy — and yes, hatred.

Unlike a poet or novelist, a public intellectual is not defined by the production of a particular object (a poem, a novel), but by something harder to pin down. Today, the term is fuzzy at best, suspect at worst. In a world obsessed with quantification, optimization and metrics, it sits awkwardly on the margins: There is no “objective” way of defining an intellectual’s impact or purpose. For these reasons, anyone and no one can be an intellectual. And those who are (or are recognized as such) face fewer and fewer institutional or market incentives to pursue the role. Certainly, there is a cultural function intellectuals can fulfill, and Sarlo embodied it. But there is also a moral dimension to intellectual life that speaks to me more forcefully.

Sarlo ends her memoir with an aphorism from Kafka: “From a certain point onward there is no longer any turning back. That is the point that must be reached.” She asks: Is this optimistic or pessimistic? Is Kafka invoking destruction or utopia? Sarlo gives the phrase her own twist: The point of no return, she suggests, is death. But death is not simply something that happens to us — it is something we must reach. Borrowing a phrase from the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard, Sarlo says that death becomes a goal. And the only way to approach that goal is by refusing to turn away from the present: by writing about it, examining it, looking at it with neither nostalgia nor illusion.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.