When Titi Maurice met her husband-to-be, she had a condition: To marry her, he had to learn to speak Coptic. One of only a handful of people in the world who spoke the language growing up, Maurice was determined that her children would have the same experience. Rafik, clearly besotted, did not hesitate. He had the basics of the written language from church, but Maurice taught him a living version — not the centuries-old liturgy and prayers repeated on Sundays but the everyday “Would you like a cup of tea?” or “It’s in the cupboard over there.”

Coptic is the most recent stage of the language of the ancient Egyptians, directly descended from the language of the pharaohs. First written in hieroglyphs, there was also a cursive version of the writing, known as hieratic, and later came a different form we call demotic. In the fourth century BCE, Alexander the Great conquered much of the region, bringing the Greek language with him. The famous Rosetta stone recorded the fact that hieroglyphs, demotic and Greek were used simultaneously. This find, with the same piece of text repeated in all three, enabled the decipherment of hieroglyphs exactly 200 years ago.

The Greeks left many traces behind in Egypt, not least on the indigenous language. In fact, the name we use for Egypt today comes from the ancient Greek “Aigyptos,” which led to the words “Qibt” in Arabic and “Copt” in English. But it was the spread of Christianity to the area that cemented the Hellenism of Coptic, bringing as it did substantial amounts of Greek vocabulary to both the spoken and written languages. Christianity also gave the language its modern form: Coptic is written in an adapted version of the Greek alphabet, with seven extra characters for sounds that are not in the Greek language.

One of the earliest uses of the language written in this alphabet comes from the letters of St. Anthony (who supposedly lived a very long life, from 251 to 356), the ascetic “father of monks” who eventually settled in a cave in the eastern desert of Egypt between the Nile and the Red Sea. The cave is not only remote from any settlement but also quite a hike up a mountain, as I found out one hot April day. After toiling up the thousands of steps, I squeezed through a crack in the mountain only just big enough for a human, grateful for the cool inside the rock. I slowly made my way down the passage, giving my eyes time to adjust to the dark, though the stairs helpfully now have a handrail, necessary for the unwary pilgrim stumbling in the dark. When I stepped down into the saint’s cave, I found myself astonishingly alone, able to recover from the heat a little and meditate on solitary life in such a place. There is a visceral feeling of connection to this early saint’s history, who is so familiar from art and church frescos.

This sense that Christianity has deep roots in Egypt was repeated many times. When I made it back down the mountain to the cooler peace of the monastery, I was shown one ancient structure after another by a guide and monk, the Rev. Ruwais Antonius, including the foundations of fourth-century monastic cells, possibly belonging to monks under the guidance of St. Anthony himself; the church with 13th-century frescos, newly restored; the original stone refectory, the table and benches carved out of the same massive piece of rock (and clearly designed when people were smaller, perhaps connected to spartan existences in the desert — my legs could fit in only with some contortion).

In Cairo, I visited the church of St. Sergius and St. Bacchus; it was my fourth or fifth ancient church that day, and I was confused by the sudden increase in tourist numbers. But following the crowds into a side chancel, I understood why: There was a well where Mary, Joseph and Jesus were said to have drunk on their flight into Egypt away from Bethlehem (and Herod’s wrath) and the crypt was built around the cave they supposedly sheltered in. Another day I visited the new Cathedral of St. Mark, the seat of the Coptic pope (a complex equivalent to the Vatican, though the guards are not so finely dressed), finding relics of this evangelist — author of one of the four accepted gospels of the life of Jesus — in a specially-built shrine. (It was harder to connect to this early Christian period than in St. Anthony’s spartan cave, given that the modern building is newly decorated in pure kitsch, but being in the presence of one of the Bible’s authors is awe-inspiring.)

This rich history of apostles and saints began to change with the coming of Islam in 641, along with the meaning and use of “Coptic” itself. Etymologically, “Copt” simply means Egyptian, but after the Arab-Islamic conquest, the meaning shifted to refer only to those Egyptians who did not convert to Islam — hence the popular meaning to this day of Copt as an Egyptian Christian. Even this, however, is not a clear-cut category. Although the Coptic Orthodox Church is the most representative of Christians in Egypt, there are also Protestants and Catholics in the country, a result of a missionary presence in the 19th and 20th centuries, who make up a small proportion of this “Egyptian Christian” category. All have “Coptic” appended to their denomination in Egypt, yet not all are part of the “Coptic Orthodox Church.”

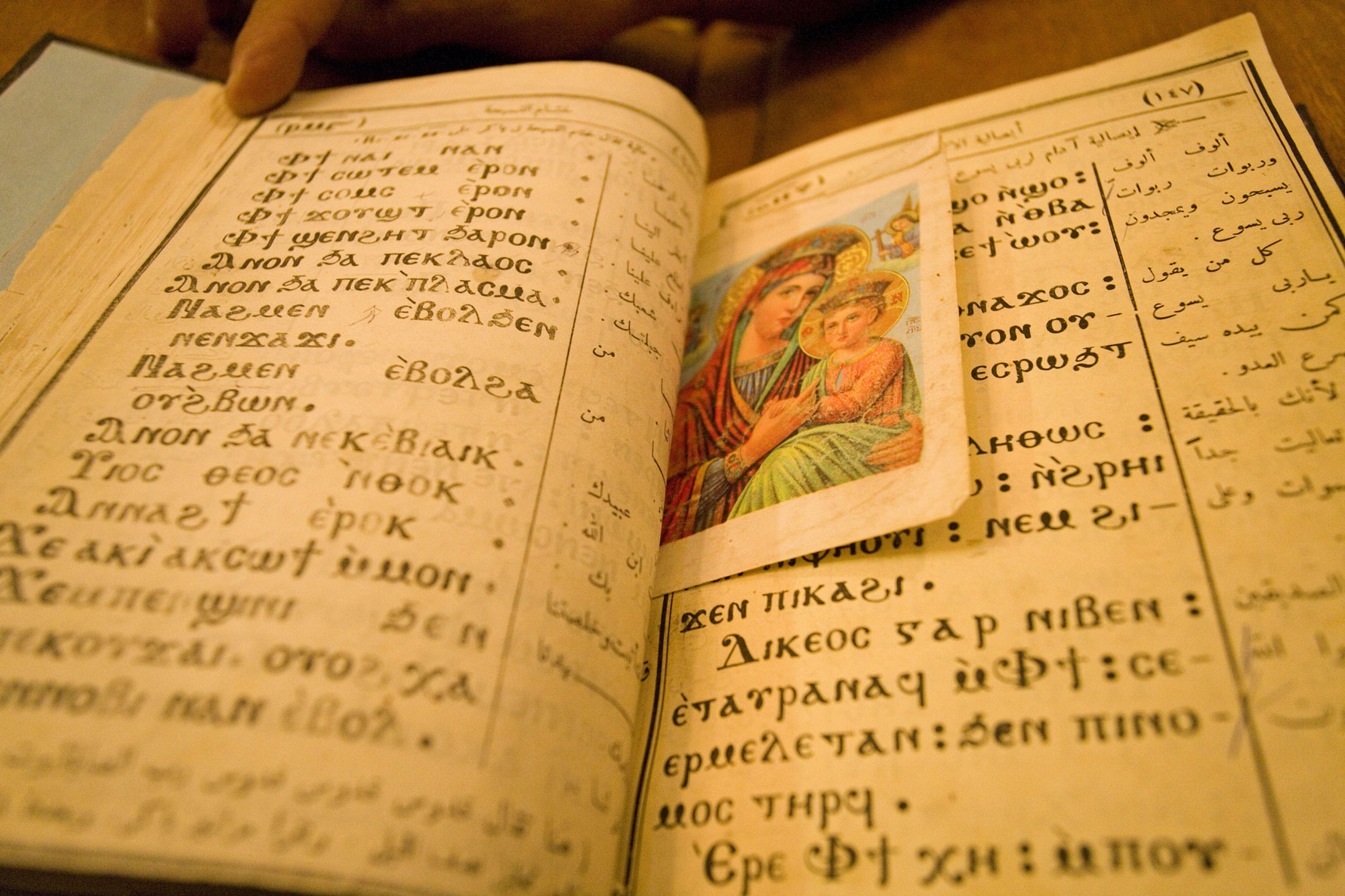

The Coptic language continued to be ubiquitous, as is clear from the reference to an interpreter when the Caliph al-Mamun visited Egypt in 830; the translation of medical, alchemical and other philosophical texts from Arabic into Coptic; and the production of popular poetry, all of which show it as a living language. But this, too, slowly changed, and by the 14th century, bibles and other liturgical works written in Coptic had parallel translations and explanations in Arabic. With increasing conversions to Islam, and Arabic as the language of the state, Coptic appears to have withered as a spoken language; like Latin in the West, it became the preserve of clergy and scholars alone. As the Bishop Athanasius of Qus wrote in the 14th century, “For the people of this time in this land, their language has become forgotten … others have not abandoned their language as we have ours.”

Yet here is Maurice in front of me, writing out phrases in Coptic, explaining how she taught her husband to understand “We’re late, hurry up,” and how their family WhatsApp group is all in Coptic. The decision they made when they were first engaged means their children are in a group of only hundreds of people in the world (the exact number is hard to discover): native speakers of Coptic, like their mother, who in turn inherited it from her parents. “When I was a child, we used to speak only Coptic at home,” she tells me. Her father made it a rule in the house, knowing they would learn Arabic at school, on the street, with friends. “Coptic was to be the only language spoken, so we could practice it and be able to save it.” Her father enforced this rule despite the fact that he himself grew up in an Arabic-speaking home; it was her mother who grew up as a native Coptic speaker, and, like her daughter after her, made it a condition of her marriage that he would learn. With the fervor of a convert, he became committed to saving the language, a commitment he passed on to his daughter.

How can this be, given the 14th-century bishop’s laments, the bibles with Arabic explanations starting around the same time, the lack of texts or letters except liturgical after the 14th century? Although there are reports of villages in Upper Egypt that have used the language in an unbroken chain, this is hard to verify. There are no sources from the Ottoman period referring to Coptic as a spoken language; the only clues of anything like this are in Western sources, and they only mention words used here and there. Further, there are many historical factors contributing to Coptic being used less across society — notably Arabization and attacks on minorities, with the Fatimid Caliph Al Hakim destroying churches, and the later Mamluk period seeing harsh crackdowns on Copts and other communities. None of this conclusively means Coptic was not used — as a minority in the empire, the language spoken in homes might not have attracted the attention of those writing books, so it could have continued, albeit hidden away.

What is more likely than unbroken continuity is that Maurice’s home language is down to the work of one passionate revivalist in the 19th century: Iqladius (or Claudius) Labib (1868-1918). Labib compiled the first Coptic-Arabic dictionary, wrote around two dozen further works, liturgical and linguistic, and founded the (short-lived) “Ayn Shams” (“Heliopolis”), the first Coptic-language periodical. Like Maurice’s father generations later, Labib insisted on Coptic-only in the home and encouraged friends to do the same. This came at a time when there were not only more Coptic nationalism movements but also other nationalisms were investing in reforming languages — in the Middle East, notably Turkish (culminating in language reforms by Turkey’s first president, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk), Persian and the development of modern Hebrew.

In 1934, the scholar De Lacy O’Leary wrote, “This praiseworthy effort had only a moderate degree of success. Occasionally one still meets recollections of persons stated to have been Coptic speaking only a few generations ago; as a rule these recollections are of enthusiasts who tried to follow the Coptic renascence projected by Labib.” A moderate degree of success maybe, but success that has stubbornly endured, and now there are new strands of Coptic revivalism emerging.

Hany Takla is a man with a mission. As he speaks to me from his home of 52 years in Los Angeles, his thick Egyptian accent betrays one aspect of his identity, but it is the Coptic part, encompassing language, religion and culture, that is his passion. His daughter used to complain that his children were second-class — his first commitment was to the Coptic language. No, he would reply, you come third; first Coptic, second your mother, third my children. “She didn’t like this joke,” he laughs now. (Her name alone illustrates his fixation: Nefertiti.)

He first felt this calling at 12 years old. “All of a sudden, when I was walking to church, a couple of blocks away from us in Cairo, it dawned on me: I needed to learn Coptic.” He later discovered that he was not the first in his family to do so. “Several generations ago in Upper Egypt, some of my family actually spoke in Coptic, and our society owns a manuscript that was written by a cousin of my great-grandfather. But I did not know all those things then.”

Two comments from a professor at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) refined Takla’s mission. The first was about the Old Testament. There are plenty of fragments of this text in Coptic, but at this point there was no complete version, based on collated and edited manuscripts. “He said it was probably complete, but the work would have to be done by people in the clerical college, in Egypt, to show this.” Takla had already bumped up against the role of the church in the Coptic language and was skeptical of the outcome. “So that was like a silent calling, for me to work on that.” Which he did, eventually writing a thesis on the Coptic Old Testament, demonstrating that it was not complete in any of the Coptic dialects, and preserving what there was, digitally.

The second comment was a throwaway line during a lesson in response to a question on pronunciation. “He said, ‘this is the best we can do for a dead language,’” Takla laughs. “Well, I took that personally!” Those two comments shaped the rest of Takla’s life. In 1979, he founded St. Shenouda the Archimandrite, a society to promote Coptic culture. “I was thinking that we needed to think about the new generations, how to keep them in the church in the diaspora. And I thought the only real link is the language.” And so he focused on its revival, devoting himself to the project. “When I get into anything, it’s about what value it has for Coptic,” he says, referring to Coptic heritage writ large, and I begin to see why Nefertiti might feel second-class. “My interest in technology has to do with Coptic — if it can serve Coptic, I do it.” He bought an Atari 800, the programs on a tape, to design Coptic letters in the 1980s. He put manuscripts onto CD-ROMs in the 1990s. The digital Old Testament is an invaluable resource for many scholars. Wherever he went, he talked about it: From his high school friends to his engineering colleagues, everyone knew about the Coptic language.

Maurice’s motivation, on the other hand, is not so much this manuscript history of the Coptic Church, though religion is a part of her identity. Instead, it is the living language she champions. Her plans for reviving the use of Coptic are many and varied, from using only Coptic in WhatsApp groups to creating videos of making simple dishes — even cups of coffee — giving the instructions in Coptic. She knows that people can learn, as her own husband did not speak it before they were married, though he knew the basics from Sunday school. “When he started learning, I used stickers and wrote the names of things in Coptic, since he already knew the letters and how to read them from church.” She gives an example from the home. “I would write the word for the ‘closet’ in Coptic — ‘tisini.’ Every time he opens the closet, he sees the word, and he starts to memorize the word.”

As we talk, I hear two major aspects to Maurice’s zeal, on two very different scales: her family background, with her mother a native speaker and her father banning Arabic in the home, and simultaneously the deep history of her country. “As long as Coptic exists, no matter how small the number of speakers, it connects us to ancient Egypt,” she told me. While this is potentially of immense value to Egyptologists, her claim that “there is no need to decipher the language because it can be understood, just as I inherited it,” is perhaps an overstatement given how much languages tend to change over time, though there is an argument that the evolution of Coptic has been particularly slow, ironically thanks to the fact that for so many centuries it has been preserved as a written, rather than spoken language, rendering it more stable. And Maurice has plenty of examples to show the continuity. “The cobra snake that you see on the head of the pharaohs [in hieroglyphs] — this is the same as the word in Coptic — ‘ouro’ — which means king.”

This older, wider sense of Coptic as the language of the pharaohs rather than the language of the Christians is gaining traction among Egyptians all over the world, along with the argument that the Coptic identity is ethnic rather than religious — an ethnicity going back to ancient Egypt, bypassing the Arab period of Egyptian history. “Essentially, this equates being Coptic to being authentically Egyptian; to having a legitimate historic claim to an Egyptian identity,” wrote the scholar Mirna Wasef for Egypt Migrations. Takla has observed the same phenomenon, especially since 9/11, and especially among the younger generations of the Egyptian diaspora in the West: “They wanted to divorce themselves from an Arab identity, both Muslims and Christians.” Takla saw that reflected in an increased number of people learning Coptic, his own classes growing in size, year on year.

As I wander around medieval Cairo, in the environs of Al-Azhar, Hussein and Sayeda Zainab mosques, the Arab history does not seem so easily dismissed, reinforced by the party atmosphere that Ramadan brings to the evenings. Nor is it so easily dismissed by minorities suffering sectarian oppression and violence, which took on a religious aspect during the rule of President Mohamed Morsi and did not disappear under President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi despite his rhetoric of inclusion. Some Christians are claiming a Coptic identity to distance themselves from an Arab-Egyptian identity, a trend that has been particularly marked since the 2011 revolution.

“Since at least 2013 to 2014 there has been an uptick of interest in restoring Coptic as a living language and also in restoring and standardizing liturgical hymns — the music in the service,” Michael Akladios, lecturer in historical studies at the University of Toronto, told me, referring in particular to increasing oppression of Christian communities during — and following — Morsi’s tenure. Akladios observed new societies and movements springing up around the diaspora at the time, and even founded his own, which became Egypt Migrations, devoted to exploring and documenting diaspora experiences. “Coptic Twitter also became a force to be reckoned with,” he said, shaping an identity that was entirely separate from anything Arab. Seeking markers of ethnic distinction, he added, “People were basically becoming enthused around these questions of language, tradition, liturgical practice and so on.”

Takla tells me about a political party in Egypt, founded in the wake of the 2011 revolution, which included in its manifesto a call to teach Coptic as a second language in schools. But this unifying aspect to the Coptic language is not welcomed by all. “There is a problem, in that the church feels that Coptic is Christian and is therefore its own property,” he said, a problem also noted by Akladios. “Unless you’re a bishop,” he explained, “you can’t get access to church archives. They are literally under the pope’s residence in the patriarchate — everyone knows they’re there, but no one can access them.” The church’s protectiveness over its history is a sign, in a way, of its fragility: The inability to welcome researchers, and hence scrutiny, shows its need to cling to the status quo of being the guardians of the Coptic identity. But the effect is to close it off to many who are interested, even passionate.

The church’s control has made it more difficult to conduct research but has also meant interest pops up in other ways — such as new organizations in the diaspora like Egypt Migrations or Takla’s St. Shenouda, classes taught outside the church and individuals like Maurice creating new content and disseminating it via social media channels. The church can no longer claim to be the only authority in defining Coptic identity. And there are even splits within the church, with prominent clerical voices in Egypt telling their congregation that they are free to pray in Arabic — it’s all the same to God — advice that is unpopular among Copts championing the language as part of their identity.

From the hieroglyphs on the walls of tombs to the Greek letters on a keyboard today, the language of Egypt has survived — just — through millennia, expressing different belief systems and cultural norms, written in many different scripts. It has mostly endured through the Coptic Church, with its services, prayers and Sunday school lessons. But there is no doubt — as seen in Maurice’s home — that it can be used for everyday life. Whether it flourishes in this living form is down to a fringe group but one that hopes to spread the word, literally.