At the “March for Life” in Washington, D.C., held in January of this year, the Colorado-based nonprofit Save the Storks distributed hundreds of colorful anti-abortion placards. Most of them were light blue, adorned with catchy slogans. “I will be their voice,” read one. “Pro-life is pro-woman,” was another.

But one of them was not like the others. It featured an expressively realistic painting depicting the Visitation of the Virgin Mary, who is pregnant with Jesus, and Elizabeth, pregnant with John the Baptist. It was painted in the technical tradition of the 15th-century Dutch masters, showing the two women facing each other and cupping their rounded bellies. But unlike most classical paintings of the visitation, this 20th-century rendering by Swiss artist Bradi Barth shows not only Mary and Elizabeth but their unborn children, too. A fully-formed Jesus and John can be seen waving at each other from their mothers’ transparent wombs. A simple quote by the late American gynecologist Bernard Nathanson completes the placard: “Fewer women would have abortions if wombs had windows.”

Nathanson famously found himself in an unusual position in the late 1970s: The former abortion provider, who had overseen tens of thousands of abortions, was suddenly at the heart of a movement he had once tirelessly worked against. The man who had helped pass the landmark Roe v. Wade ruling, granting women a constitutional right to an abortion, was now speaking out with fervor against the procedure. But Nathanson wasn’t only speaking out — he was actually showing, using something new and powerful — something that would revolutionize the anti-abortion cause. It was the ultrasound.

In 1984, Nathanson transformed this new aspect of prenatal care into a powerful political tool and set out to change the way people thought about abortion, not through words, but through images. With “The Silent Scream,” a 28-minute film which he personally narrated, Nathanson gave Americans a “window into the womb,” using ultrasound technology to show a 12-week abortion “from the victim’s vantage point.” He filmed and described the fetus as a living person, as a child experiencing pain, fear and distress at the hands of the doctor, and whose “silent scream” could almost be heard as it was torn from its mother’s womb.

The film’s influence was immediate and powerful. Praised to the skies by President Ronald Reagan, shown on national TV and in schools and churches well into the 2000s, “The Silent Scream” triggered a dramatic shift in the abortion debate, reshaping public perception of fetal life and death.

The producer of “The Silent Scream” at American Portrait Films called it “the atom bomb of the pro-life movement.” Anti-abortion advocates embraced the film as a political game-changer, a tool that could finally win the war for public opinion.

In the mid-1980s, with the United States Congress still deadlocked over abortion and the Supreme Court having twice reaffirmed “a woman’s right to choose,” the political attack on abortion rights moved further into the terrain of mass culture and, most importantly, imagery, by making invisible life visible.

Karyn Valerius, who teaches American literature at Hofstra University, remembers seeing the film on TV when it first aired. “I was in high school in 1984,” she told New Lines in a Zoom interview, “and I remember being really taken aback that something so graphic would be shown right after the evening news.” At 16, Valerius says she immediately recognized the political potential of “The Silent Scream”: “It was essentially a horror movie but, unlike everything we’d seen before, it was rooted in science, not faith. That was new.”

Thirty years later, Valerius published an article, “A Not-So-Silent Scream: Gothic and the U.S. Abortion Debate,” explaining how, in the 18th century, those who wanted to criminalize abortion used gothic discourse and imagery to vilify the practice. In the post-Roe world, she argued, the very same discourse was resuscitated to equate abortion — even when legal — with murder. “The Silent Scream,” she told New Lines, marked a turning point in the abortion debate of the 1980s “not because it offered new legal arguments, but because it used visual technology to make a moral one, one that is still used to this day.”

Ten years after Roe v. Wade, Nathanson managed to turn the focus away from the horror stories of women undergoing illegal back-alley abortions to the horror movie of a fetus undergoing a legal one. In doing so, Valerius said, Nathanson propelled “fetal personhood” away from religious discourse and into the political arena.

Most importantly, “The Silent Scream” marked a watershed moment in the movement toward the subject of fetal personhood in the U.S., bringing it to the forefront of public consciousness. In the 1980s, fetal personhood — the notion that fetuses and embryos should be considered legal persons under the Constitution, with rights equal to those of those who carry them — was just that: a notion. But in 2024, fetal personhood is effectively a reality for nearly one-third of American women of reproductive age living in some 19 states where abortion is unavailable or severely restricted — in no small part thanks to a film that came out four decades ago.

To understand the seismic impact of “The Silent Scream,” one must first understand Nathanson. Born in New York City in 1926, he chose to study gynecology, like his father before him. Nathanson gained national attention in the late 1960s as co-founder of the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL, now known as Reproductive Freedom for All). Alongside the writer and activist Betty Friedan, he campaigned for the legalization of abortion in the U.S. and was instrumental to the success of the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973.

But one year later, while chief of obstetrics at New York’s St. Luke’s Hospital, Nathanson became increasingly uneasy with the procedure. In a much-publicized article in the New England Journal of Medicine, he confessed, “I am deeply troubled by my own increasing certainty that I had in fact presided over 60,000 deaths.” His inhibitions, he said, were not of heart or spirit, or even driven by religious conviction (though raised in the Jewish faith, Nathanson was a self-proclaimed atheist). No, he said: His inhibitions were intellectual. Scientific, even.

Though Roe v. Wade had explicitly avoided answering the question of when life begins, Nathanson felt that new technologies had opened his eyes. “There is no longer serious doubt in my mind,” he wrote in his 1974 article, “that human life exists within the womb from the very onset of pregnancy.”

By the mid-1970s, advances in medical technology, particularly ultrasound, had given Nathanson a new perspective on fetal life. After the Second World War, scientists had begun turning sonar technology away from submarine warfare and toward women’s bodies. The fetus had gone public.

Before ultrasound, Nathanson viewed abortion as “bloodless, utilitarian problem solving,” he said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, adding that, with abortion, “a woman had an unplanned pregnancy; all you did was wipe the fetus out.”

When the pelvic ultrasound gave him a window into the womb, Nathanson began to see the fetus not as an invisible clump of cells, but as something that looked human, with legs and arms, a head, fingers. Something he began to think of as an “unborn child.”

“For the first time,” he wrote in 1974, using humanizing language, “we could really see the unborn child, measure it, observe it, watch it, and indeed bond with it and love it.”

And if a fetus looks like us, Nathanson began to wonder, does it also feel pain like us?

Reagan certainly thought so. Ten years after Nathanson’s change of heart, the Republican president was quoted saying a fetus “often feels pain” during an abortion — “pain that is long and agonizing.” In his memoir, “The Hand of God: A Journey from Death to Life by the Abortion Doctor Who Changed His Mind,” Nathanson credited Reagan with first broaching the topic of fetal pain. “I mulled it over,” Nathanson wrote, “and I thought there’s only one way we can resolve this issue, and that’s by photographing an abortion, beginning to end.”

Through acquaintances, Nathanson arranged to film ultrasound images of an abortion at 12 weeks (the end of the first trimester), seeking to prove that abortion was not just the removal of tissue but the painful destruction of a human life. He serves as both the medical expert and narrator of the film, describing the events of the “live abortion” as they unfold on camera.

In a debate marked by impassioned rhetoric on both sides, the gruffly handsome 58-year-old presents himself as a coolly scientific intellectual. His smoky-gray hair, pristine white coat and thick, sensible glasses establish him as a de facto figure of medical authority. As the film opens to chilling organ music, his clinical monotone seeks to reassure the viewer: “My name is Bernard N. Nathanson. I’m a physician, a practicing obstetrician and gynecologist. And I think I’ve had a passing experience in matters of abortion.”

“New technologies,” Nathanson explains, “have convinced us beyond question that the unborn child is simply another member of the human community.” Thanks to ultrasounds, he adds, we can now see and experience abortion from the victim’s vantage point. And so, he narrates flatly, “we are going to watch a child being torn apart, dismembered, disarticulated, crushed and destroyed by the unfeeling steel instruments of the abortionist.”

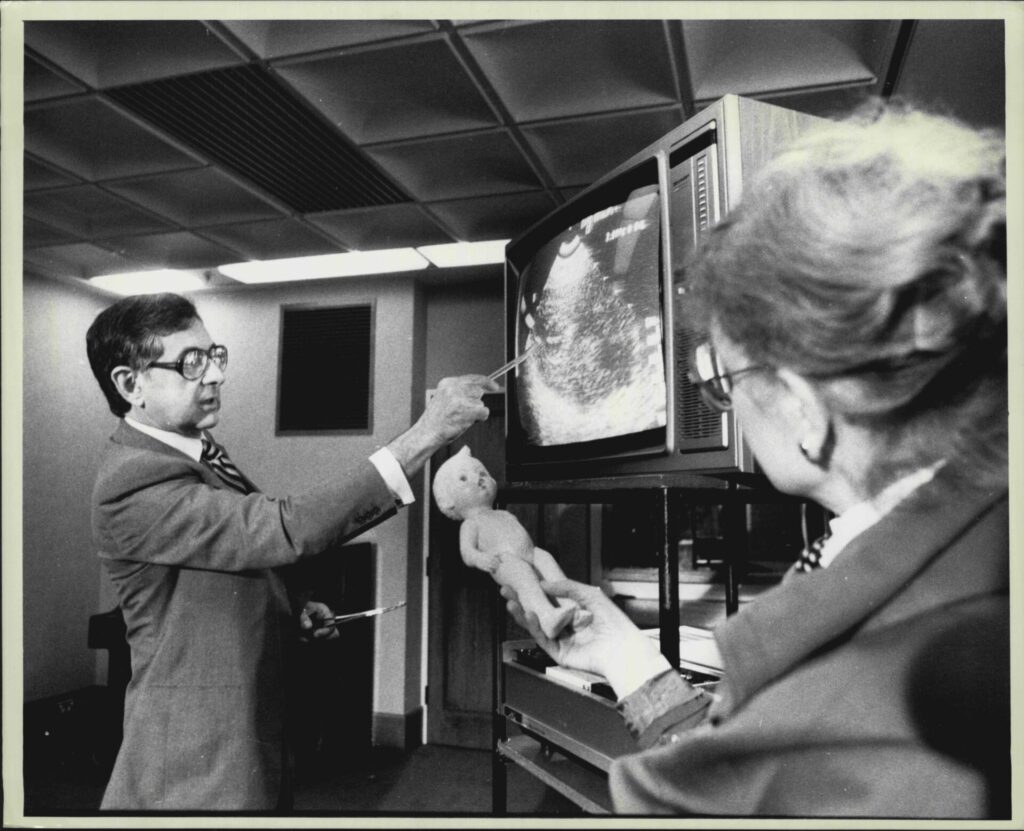

So begins “The Silent Scream.” The images are grainy and vague but Nathanson is there to translate them for us, armed with a pointer and his medical expertise. “The child,” he narrates, “senses aggression in its sanctuary” and moves in an “agitated” manner away from the surgical instruments in a “pathetic attempt to escape.” Its heart rate increases as it “senses mortal danger” and, he notes, pointing to a fuzzy image, it opens its mouth in a “chilling silent scream.”

This, he says, to the sound of a shrill musical accompaniment, “is the silent scream of a child threatened imminently with extinction.”

In an address to some 70,000 participants at the 1985 March for Life in Washington, D.C., Reagan said that “if every member of Congress could see that film, they would move quickly to end the tragedy of abortion.” Soon, “The Silent Scream” was shown in the White House and copies were distributed to the entire Congress, as well as all nine members of the U.S. Supreme Court.

The film premiered on televangelist Jerry Falwell’s immensely popular “Old-Time Gospel Hour” and aired five times over the span of a month on major television networks. Falwell also presided over the Moral Majority, a political organization which played a key role in the mobilization of conservative Christians as a political force: He ordered 50,000 copies of the film to distribute among the organization’s chapters across the country. “It may win the battle for us,” the minister said in a 1985 interview with Time Magazine, encouraging anti-abortion groups throughout the U.S. to embrace “The Silent Scream” in their propaganda efforts.

“The Silent Scream” was then translated into Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Japanese, Swedish, Polish and Russian. VHS copies (at $100 apiece, a huge sum for a tape in the mid-1980s) were sent to the French Senate. Pope John Paul II, who met with Nathanson in a private audience, cited the film in a TV interview watched across the globe: “Camera,” he said (without citing the man behind it or his politics) “has captured the desperate struggle of an unborn child in its mother’s womb.”

Lawrence Lader, a co-founder of NARAL, described his former colleague as “a master PR man.” “He has seized on a hell of a gimmick here, and he does it brilliantly,” he told The Washington Post.

Experts were quick to point out the numerous factual inaccuracies in “The Silent Scream.” At 12 weeks, scientists argued, a fetus lacks the neurological development necessary to feel pain, let alone scream. A few weeks after the filmed premiere on national TV, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued statements debunking Nathanson’s claims, noting that the movements shown in the film were reflexive, not purposeful, and that the fetus’ open mouth — depicted as a scream — was most likely a normal, non-painful movement. The ultrasound images and the fetus model used were also misleading, experts added, appearing to show a fetus the size of a full-term baby rather than two inches long, its actual size at 12 weeks.

“We are being fed a medieval morality play,” the political scientist and pro-abortion rights activist Rosalind P. Petchesky wrote in her 1987 cultural critique of the film. “The Silent Scream,” Petchesky argued, marked a dramatic shift in the contest over abortion imagery. With formidable cunning, it translated the (by then overused) still images of the fetus as “baby” into real-time video, thus bringing the fetal image “to life” outside the womb.

“Using ultrasound technology, which was still new and dazzling to the general public, was exceedingly clever,” Lynn Morgan, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Mount Holyoke University, told New Lines. Morgan wrote a cultural history of human embryos entitled “Icons of Life,” in which she explores how visual technology led modern citizens to envision fetuses and embryos as images of “ourselves unborn,” and profoundly shaped the current fetal personhood movement.

“After Roe v. Wade,” Morgan told New Lines, “anti-abortion activists concentrated on making the fetus into a subject worthy of our attention and sympathy, something worthy of mobilizing around, of saving.” By enabling fetal images to move in “The Silent Scream,” Nathanson “further personified them as fetal subjects.”

The power of the film, she adds, is that it capitalizes on a society that, though more visually oriented than ever, is still prone to take images at face value. “The condition of productions of ‘The Silent Scream’ are never spelled out,” she says. “So focused is the camera on the inside of the womb that the viewers forget about whom the womb belongs to.” They forget about the mother, referred to only as “the sanctuary” in the film.

In “The Silent Scream,” the “baby” is seen floating around on screen, completely out of context, divorced from the womb itself. The image and narration are entirely focused on the unborn, reducing the mother to the status of “fetal incubator,” Morgan says. “We never see her face,” she adds, “just her legs in stirrups and the blood streaming out of her.”

Karen Newman, a scholar of Shakespeare who took a sabbatical to publish her 1996 book “Fetal Positions,” argues that modes of visualizing fetuses have always had a profound impact on how society treats mothers. “Today,” she told New Lines, “the fetus is viewed almost as a freestanding individual, while women have all but disappeared.” Thanks to ultrasound, we have come to visualize the fetus as a sort of “spaceman,” she added, “an autonomous being floating in a neutral environment.” But no fetus is suspended anywhere, she insists, but “anchored to the placenta, housed in the womb, and wrapped in the flesh of a living woman.”

The framing of “The Silent Scream,” then, is most notable for what it excludes: the woman. In order to make the fetus visible, to provide a window into the womb, it made the woman disappear.

Yet all of these rebuttals, old or new, do little to diminish the film’s impact.

Confronted with the claim that it is physiologically impossible for a 12-week-old fetus to scream, Nathanson had a ready response. “Of course it is,” he told The Orlando Sentinel in a 1985 interview. “It’s metaphorical license. Everyone knows that. I don’t think that really requires any comment.” But, he added with his characteristic dark humor, “If pro-choice advocates think that they’re going to see the fetus happily sliding down the suction tube waving and smiling as it goes by, they’re in for a truly paralyzing shock.”

“The Silent Scream” was never intended to be a strictly factual medical documentary; it was a piece of visual rhetoric designed to stir emotions and change the hearts and minds not just of the young, the impressionable and the pregnant, but also of legislators voting on fetal personhood.

The film’s emotional megatonnage hit pro-choice forces hard. Planned Parenthood responded to Nathanson with “The Facts Speak Louder than The Silent Scream,” a nine-page, purple-covered critique which addressed the film’s claims one by one. The brochure described the film as “riddled with scientific, medical, and legal inaccuracies as well as misleading statements and exaggerations.”

But the notion that the fetus is nothing but a “clump of cells” is unconvincing when placed next to the image of a fat-cheeked fetus (erroneously) described as sucking its thumb and screaming in pain. “They have been stronger on emotion, reaching people in their hearts and guts, while we were strong cerebrally,” said NARAL Director Nanette Falkenberg.

And so, pro-abortion activists decided to launch their own emotional counteroffensive. Women appeared in national newspaper ads and stood in front of microphones in public spaces around the country, discussing their abortions in a new, highly personalized campaign. Many read emotional letters they had written to President Reagan describing their illegal abortions in graphic detail. NARAL’s Silent No More campaign toured 30 states and rounded up some 40,000 letters to capture public sympathy.

The visual culture of fetal life and death that Nathanson helped to popularize with “The Silent Scream” would go on to influence a host of anti-abortion efforts in the years to come.

Crisis pregnancy centers, often affiliated with anti-abortion organizations, began offering free ultrasounds to pregnant women as a way to dissuade them from seeking abortions. The Colorado non-profit Save the Storks — which distributed “Window to the Womb” posters at the 2024 March for Life — even has its own mobile ultrasound van to do just that. In December 2023, the anti-abortion group Live Action came out with an app called “Window to the Womb,” which they describe as “a visually powerful tool in ministering to those who are unexpectedly pregnant and need to know what is actually happening with the life developing within them.”

Proponents of fetal personhood understood the emotional impact of seeing a fetus on a screen and used this visual strategy to promote their cause. In the political arena, ultrasound images became central to the arguments in favor of restrictive abortion laws, including “heartbeat bills” that seek to ban abortions as early as six weeks, when a fetal heartbeat can first be detected. Such laws rely on the same visual logic introduced by “The Silent Scream”: If the fetus can be seen, heard and imagined as a person, it must be protected as one, regardless of what the woman thinks or feels.

And thus, the strategy of fetal personhood becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. In a visually oriented society, the ever-increasing public presence of the fetus — from ultrasounds plastered on fridges to gender reveals and fetal keepsakes — further enshrines its legal personhood in the public imagination.

“The Silent Scream” was more than just a film — it was a cultural intervention that changed the way Americans saw fetal personhood. By using ultrasound images to make the fetus visible, Nathanson tapped into the power of visual culture and helped to fuel a growing movement to grant legal rights to fetuses.

The conversation it sparked continues to shape the way Americans think about life, autonomy and the rights of the unborn. Forty years later, the American public is more deadlocked on the question of fetal life than it is on the question of legal abortion, and the impact of “The Silent Scream” is louder than ever.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.