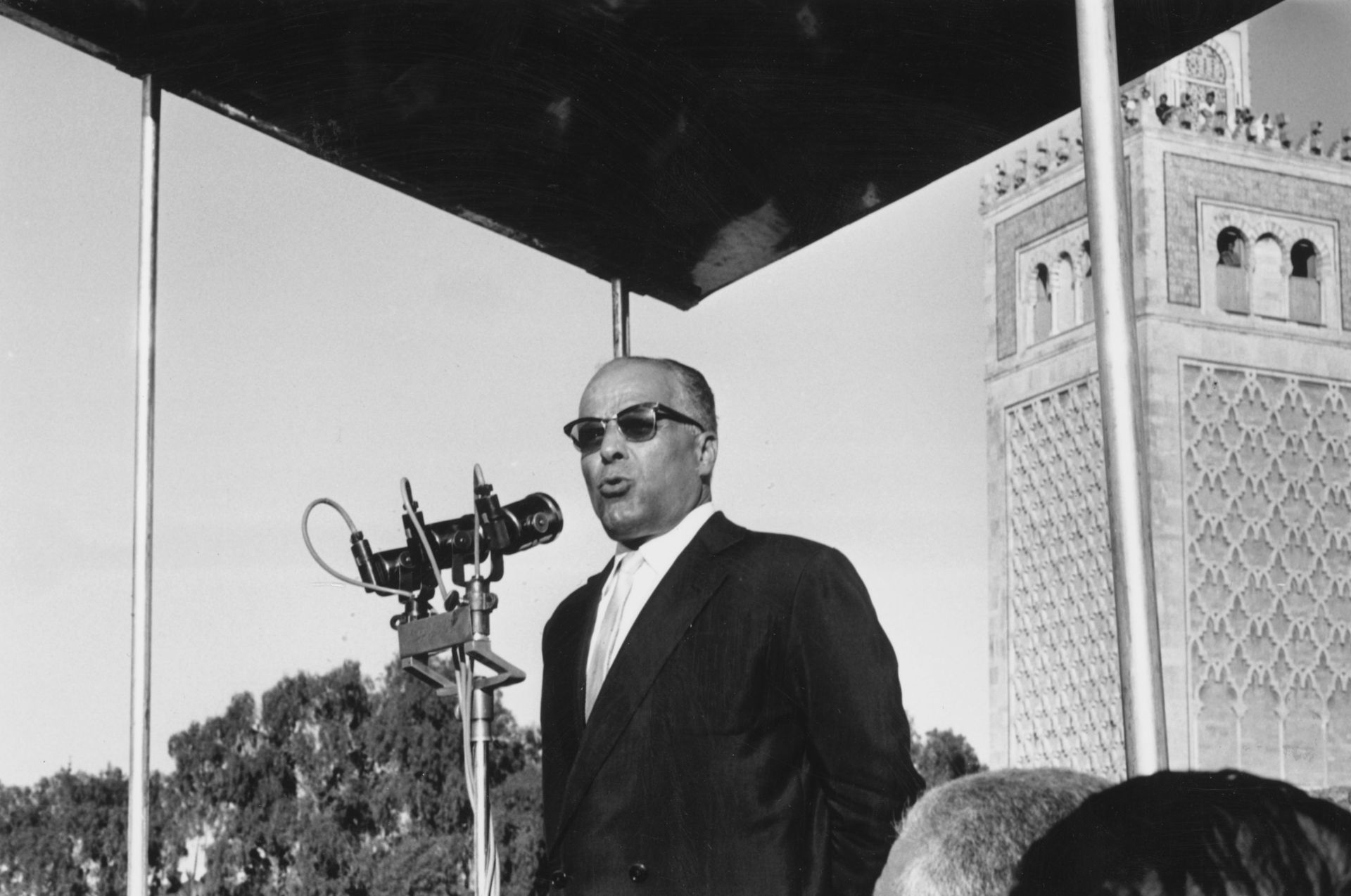

One day in March 1962, as Tunisian President Habib Bourguiba addressed the nation live on television during Ramadan, he raised a glass of orange juice and drank it, breaking the sacred fast and calling on his countrymen to do the same. The gesture was shocking, and Bourguiba’s boldness sparked widespread controversy among Tunisians and Muslims at large over the issue of breaking the fast in public during one of the holiest months of the year. Bourguiba had substantial political goodwill in the young postcolonial nation — and big ambitions. He was celebrated as the liberator of Tunisia from French colonialism, with an economic and social plan to build the country from the ground up. To accomplish that, he called on people to gather their strength to help his government succeed, instead of draining their energy during Ramadan.

While Bourguiba clearly understood the power of his act — how subversive and scandalous it would be — he likely overestimated the support his appeal to break the fast would garner. Instead of rallying people to his modernizing call, his toast caused a rift in his image as both a ruler and a person, and opened the door to a new kind of political opposition in Tunisia.

This incident set off ripples of tension around the fast of Ramadan that have been felt in Tunisian political life from the country’s independence until today, in a manner unparalleled in the rest of the Islamic world. Bourguiba’s political use of fasting began in 1960, when he first called on his citizens to break their fast during the day in Ramadan to gain strength in their struggle against poverty and “backwardness.” The saga still continues, and every year a debate rages in Tunisia between those defending the freedom to openly break the fast, on the one hand, and those calling for respect for religious rituals and mores on the other. This debate is not novel; it echoes a deep and old cultural divide between two blocs: conservatives and modernizers. The Ramadan fast became a lightning rod for this polarization, an arena where the power dynamics between the two blocs manifest, along with their position vis-a-vis the ruling authority.

Bourguiba’s call to circumvent the fast — one of the five “pillars” of Islam, as they are known — took the conflict between the two groups to an extreme. He was — and remains — the foremost symbol for secularists and modernists in Tunisia, who have sanctified him and continue to reject any criticism of his legacy. The “battle of the fast” was preceded by Bourguiba’s other confrontations with religious institutions and their adherents. He had notably introduced a personal status law based not on Islamic Sharia but on civil laws more favorable to women, weakening clerical institutions’ ability to issue religious decrees in the process, and abolished the endowment system that gave financial influence to religious authorities.

Yet his call to openly break the Ramadan fast represented, to a wide segment of religious conservatives, an irreparable fissure in what remained of his and his regime’s legitimacy. It delivered a profound shock to the majority for whom Ramadan holds a sanctity surpassing any other Islamic obligation. This served as a catalyst for an Islamic revivalist movement that would later be at the forefront of political opposition in the 1970s and would even take the reins of power after the Tunisian revolution in 2011.

Conflict over Ramadan also spawned a common myth in neighboring countries about Tunisians’ relationship with fasting. It has become common in Libya and Algeria to claim that Tunisians do not fast, implying a deficiency in their religious faith. Stories, jokes and anecdotes have been woven around this claim, and open breaking of the fast has become one of the more prevalent myths about Tunisians in the wider Maghreb. Bourguiba dropped this proverbial bomb, and its fallout obscured the fact that Tunisians are like any other Muslims, with some who fast and others who abstain, including those who openly break the fast and those who do so in secret. This view, in which truth and imagination are intermixed, would not have formed had it not been for the tendency of politics to interfere in religion.

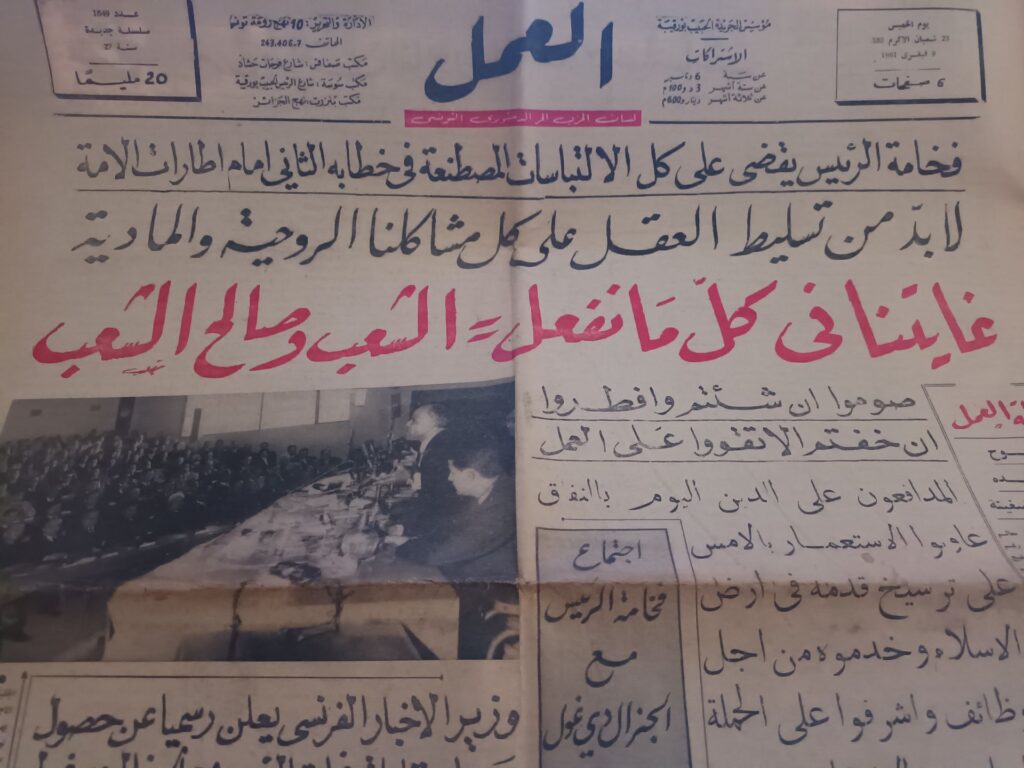

On Feb. 5, 1960, a few weeks before Ramadan, Bourguiba addressed a large gathering of state leaders and religious clerics led by the grand mufti of the republic, Sheikh Kameleddine Djait, and the dean of the University of Ez-Zitouna, Sheikh Tahar Ben Achour. At this gathering, Bourguiba called on Tunisians to break their fast during Ramadan to contribute to “eradicating poverty and backwardness,” asking the mufti to issue a fatwa supporting his opinion. Explaining his position and motives, the Tunisian president said:

The mobilization that we call for, and the inevitable and necessary continuous work required, are hindered by obstacles that the people consider to be of religious origin. Whoever is fasting and performing his religious duty according to what Islam demands, when he realizes that the weakness of his body does not allow him to work, he continues to fast, abandoning work. Whoever has this condition is not approved by his faith, according to what the mufti of Tunisia sees, and he will explain that to you himself.

Bourguiba’s invitation was primarily spurred by the harsh economic realities plaguing the nation. Following independence, the departure of French capital coupled with the feeble state of the local economy plunged Tunisia into a severe crisis. At the time, Bourguiba sought resources to implement his ambitious agenda of expanding education and health care infrastructure across the country. Compounding the crisis was a devastating drought that gripped Tunisia in 1959 and 1960, exacerbating the plight of an agrarian society dependent on rainfall for sustenance.

What Bourguiba failed to consider was the subsequent reaction of the mufti, who rejected the request and insisted in his fatwa, issued a week later, that the only exemptions for breaking the fast were travel and illness. The mufti warned Tunisians, “Anyone who denies the obligation of the fast is considered outside the fold of Islam.” He added, “He who believes in this obligation and fails to perform it, without a legitimate excuse, is deserving of God’s punishment in the hereafter, and this indeed is a grave loss.”

Bourguiba faced this outcome despite his attempts to adapt Islamic jurisprudence to his ends, citing an incident in the Prophet Muhammad’s life when Ramadan coincided with Muslims making their way, under Muhammad’s leadership, to conquer Mecca. At the time, some broke their fast for battle, while others persisted in fasting. To the latter, Muhammad said, “Break your fast, so that you have the strength to face your enemies.” Bourguiba cited this incident to argue his case by analogy. His doing so was more than merely political — in the Maliki school of thought prevalent in Tunisia, the use of deductive analogy, known in Arabic as “qiyas,” is a valid source of legislation.

The president compared the holy war that Muhammad and his companions had engaged in to the struggle of the Tunisians to build their nascent state. In that same speech, he elaborated:

All the clerics present in this hall know that Islam encourages breaking the fast in Ramadan if this grants Muslims strength against their enemies. Today’s enemies of Muslims are decadence, poverty, humiliation and indignity. Religion commands you to muster strength in facing your enemies so that you do not remain a backward nation. If you wish for God to reward you in the hereafter, you must work a few extra hours, which is better for you than fasting without work, pushing you further into deterioration.

To Tunisians, the mufti’s opposition to the president’s clerical opinions marked the first crack in Bourguiba’s legitimacy. However, Bourguiba did not remain silent; he quickly launched a series of attacks against the religious establishment and Sharia scholars, mostly through the state’s newspapers and media outlets. From Feb. 18 to March 17, Bourguiba traveled across the country addressing crowds in the squares and defending his stance, always citing rational arguments and precedents from Muhammad’s life about breaking the fast during war, equating that holy war with his efforts to build the Tunisian state. He went even further, accusing the clerics who opposed him of religious hypocrisy and claiming that, before independence, they had been “in the service of French colonialism, helping it to establish a foothold in Tunisia.” In this context, Bourguiba cited a fatwa issued by Ben Achour in 1939, during World War II, that allowed Tunisian soldiers in the French army to break their fast as long as they were in a state of war. In 1884, France had established the 4th Tunisian Riflemen Regiment, which participated in most of the wars waged by the colonial empire, including the battles to defend France from Nazi invasion in 1939 and 1940.

After independence in 1956, Bourguiba recognized that the religious establishment might stand as an obstacle to his ambitions, and thus sought to neutralize it. In that same year, he issued the personal status law that upended many family practices seen to be associated with Islam. The personal status law criminalized polygamy, legalized divorce based on the equality of the sexes and set a minimum age for marriage. Bourguiba also discriminated against veiled women, barring them from public service, and initiated a family planning campaign that involved the state distributing free contraceptives.

Starting in 1957, Bourguiba began to dismantle the religious establishment. First, he abolished the Sharia courts and unified public education, placing it under state supervision. He also prohibited Sharia education outside the official framework. Then came the most devastating blow: dismantling the material foundations of the religious establishment and its main source of financial power — religious endowments — by annexing them as state property. The endowment system allowed property or assets to be bequeathed to religious institutions for charitable causes. A centuries-old concept under Islamic law, religious endowments gave these establishments immense financial clout — all of which was lost.

Moreover, in response to the mufti’s refusal to support his position on fasting, Bourguiba sought to withdraw the mufti’s mandate to determine lunar months, Ramadan and religious holidays. On Feb. 23, 1960, he decided to adopt a scientific system of astronomical calculation to strip the mufti of any significant tasks.

At this time, a clear polarization emerged between Bourguiba — who was supported by a Western-educated elite and parts of the intelligentsia and petty bourgeoisie — and the religious establishment, backed by the conservative majority. The clerics were divided into two groups. Some supported the president, including those from the city of Bizerte and the mufti of the city of Sfax, Mohamed Mehiri. These sheikhs praised the president’s diligence and endorsed his rationale of comparing Muhammad’s holy war to the struggle of building a state. However, there were figures within the president’s camp who opposed this step from a political standpoint, fearing it could undermine the legitimacy of his regime.

In his memoirs, “Half a Century of Islamic Action,” Tawfiq Chaoui, one of the leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and a Bourguiba friend, recalls the stance of the secretary of state for finance and planning, Ahmed Ben Salah, a prominent statesman at the time. Chaoui shares what Ben Saleh confided in him: “I had not fasted during Ramadan before, but I have started fasting since Bourguiba announced his opposition to it, and many Tunisians like me had never been keen on fasting.” Ben Saleh added that Tunisians had begun “adhering to the fast to voice their opposition to Bourguiba’s religious jurisprudence,” and that the ruling Neo Destour party was considering taking “strict measures to impose the breaking of the fast on its members and other civil servants, which would exacerbate the popular discontent against the party and its government.”

Bourguiba paid no heed to critics from within his party and was fixated on creating a rupture within the religious establishment. He was not only keen to court figures from Tunisia’s clerical class but also turned to religious figures from around the Islamic world to lend credence to his call. In the same memoirs, Chaoui recalls being invited to a rally and a presidential speech in 1960 with Muhammad Sadiq al-Mujaddidi, the Afghan ambassador to Egypt, whom Bourguiba befriended during his exile in Egypt. This event took place at the Uqba ibn Nafi Mosque in the city of Kairouan, famously the first mosque built by Muslims in the Maghreb. In his speech, Bourguiba took the opportunity to reiterate his call for people to break the Ramadan fast. Chaoui writes:

The next day, we were invited to visit Bourguiba, and he asked me for my opinion of his speech the day before. I told him that this is a discussion that could take a full day by the riverside of the Nile. Shortly after, Sheikh al-Mujaddidi reproached me, saying that [Bourguiba] wished that I praised his speech and endorsed, explicitly or implicitly, his position regarding fasting. I told al-Mujaddidi that he is more worthy of this honor, as one of the most senior scholars, and he said, “I seek refuge in God. Undoubtedly, he knows my position all too well.”

In the early 1960s, Bourguiba’s modernist camp was strong in its confrontation with conservative clerics. Bourguiba enjoyed immense popularity as the liberator of Tunisia from French colonialism and for having sacrificed part of his life, enduring exile and imprisonment, in pursuit of independence. On the other hand, the legitimacy of the majority of sheikhs had been undermined by their long years of silence about colonialism, including their collaboration with the Ottoman beys and the Tunisian ruling class to legitimize the French colonial presence.

Bourguiba, wielding the power of the state, imposed his religious ideas but failed to convince Tunisians of their correctness. However, the public “fast-breaking” incident in 1962 would, years later, provide vital ammunition for the political Islamist movement that began to form in the late 1960s. That fateful day, viewed as making a mockery of any religious legitimacy the Bourguiba regime might have had, served as a watershed moment for a new political group modeled after the Muslim Brotherhood. This is confirmed by Rachid Ghannouchi, the leader of this Islamist movement, in his memoirs of Tunisian politics. Ghannouchi writes, “The birth of the movement came in the early seventies, after Bourguiba’s project revealed its animosity towards the [Muslim] umma, its faith, and its language […] as well as the growing concern to preserve our identity, driving the demand for it and for those who raise its flag and defend it.”

The 1970s witnessed a steady rise of the religious movement in Tunisia, coinciding with a broader Islamic revival across the Arab world. Mosques in the country saw increased attendance by young people, and the wearing of the hijab began to spread widely. Campaigns by the Islamic Group, renamed in 1981 as the Islamic Tendency Movement, targeted students at universities and institutes for outreach, preaching and membership. Gradually, the act of breaking the fast became less visible in public spaces. As the Islamists gained traction among the population, the ruling party’s sway began to slip and it became mired in infighting and lost popular appeal. Successive health crises diminished Bourguiba’s ability to address the public and stir up controversies around religion and identity. Though Tunisia’s political power would stay firmly with Bourguiba and the Socialist Destourian Party (Neo Destour’s successor), popular sentiment began to shift toward a more conservative view.

One incident in 1981 reveals how central Ramadan was to the cultural and political conflicts between the two camps, and the extent to which the balance between them was shifting. In July, Bourguiba was spending his vacation in his hometown of Monastir. While wandering around the outskirts of the tourist city, he found cafes, restaurants and bars closed, with tourists sitting under the shade of trees. Asking his friends what was happening, they told him, “The Brotherhood. They have threatened restaurant and cafe owners with the most severe consequences if they open their establishments during the days of fasting.” Around the same time, young Islamists attacked a tourist club in the city of Korba for serving food and drink during the day in Ramadan, prompting Bourguiba to order a security crackdown against the Islamic Tendency Movement. This was the first-ever security crackdown faced by the Islamists in Tunisia, ending with its leaders, Ghannouchi and Abdelfattah Mourou, along with hundreds of members, being handed prison sentences. However, the government of then-Prime Minister Mohamed Mzali soon issued a decision forcing the closure of cafes and restaurants during the day in Ramadan (with exceptions for tourists), as the state sought to restore its public image.

Bourguiba continued to rely on the power of the state — including his security forces — to impose his vision, but had already lost the political battle against religious conservatives, who found that imprisonment strengthened and unified their movement. The Islamists thus worked to promote themselves among their social base as being engaged in “the struggle of the righteous against the wicked, and of faith against disbelief.”

Bourguiba was ousted from power when Zine El Abidine Ben Ali led a coup in 1987. The new president was acutely aware of the valuable influence that the Islamists wielded in their struggle against the regime, and recognized the power of religious faith to mobilize popular support. So, like many autocrats, he sought to make himself and his regime appear to be religious defenders by dismantling the image Bourguiba had cultivated of the state being hostile to Islam, while still persecuting his Islamist political opponents. Ben Ali decided to reinstate direct sighting of the new moon for observation of the lunar holidays, including Ramadan, and abolished the adoption of the astronomical lunar calendar. Religious teachings and sermons in mosques, and even official television broadcasts, began urging people to fast during Ramadan. Charitable institutions affiliated with the state and the ruling party began to organize collective iftar feasts, some of which the president attended. In official media and mosque sermons, Ben Ali was dubbed “the protector of land and faith.” This new policy, with Ramadan at its heart, created a nucleus of support for Ben Ali, which later helped when he used the power of the state to confront the Islamists and finally eliminated them as a serious political force between 1991 and 1993.

When I moved to the capital, Tunis, to study at university in the early 2000s, I was surprised to see cafes open during the day in Ramadan. Coming from the cities of southern Tunisia, such a sight was unfamiliar to me. Ben Ali’s regime struck a careful balance between learning from Bourguiba’s mistakes regarding Ramadan and accommodating those who do not fast by allowing certain venues to remain open during the day — albeit with their facades covered with sheets of newspaper. Because his primary concern was maintaining the stability of his regime, Ben Ali adopted a governing philosophy centered on the “nationalization of politics,” which meant its virtual abolition. He aimed for the state and its bureaucratic apparatus to guide society without clashes over religious and cultural values that might stem from its longstanding rivalry with the Islamists, and without any external political actor being able to leverage these values against the regime. Despite these efforts, many in Tunisian society lost faith in the state’s handling of religious affairs. I recall that some of our relatives and neighbors would fast during Ramadan following the timeline and guidance of the mufti of Saudi Arabia, reflecting a broader mistrust of Tunisian religious authorities and the influence of a wave of Islamic revivalism that swept the country in the 1990s via satellite television.

The 2011 revolution not only overthrew Ben Ali but also disturbed the social stalemate between modernists and conservatives that had largely held during his rule. The contentious issues of Bourguiba’s era, including debates over the status of women, Islam and breaking the fast in Ramadan, all resurfaced simultaneously after the revolution, with openly breaking the fast once again becoming a battleground. This was particularly evident in the first three years following the revolution, when Ennahda, the party that emerged from the Islamic Tendency Movement, was in power. During this period, some preachers took it upon themselves to visit open cafes and restaurants to confront those breaking the fast, and some establishments were subjected to security campaigns under the guise of “crimes against public morality,” as per the Tunisian Penal Code, despite the absence of any legislation penalizing those who break the fast. The freedom to break the fast in Ramadan, and to do so openly, emerged as a central issue for a significant portion of modernists, tied to the broader theme of personal liberties. The political conflict in the country took a turn toward cultural and identity issues, while the revolution’s initial focus on social justice and development was sidelined.

The controversy over Ramadan did not cease with the departure of Ennahda from power. The Islamic holy month continues to stir controversy and serves as a point of political polarization between the two camps, with the state maintaining a central grip. The Tunisian constitution upholds individual liberties, including the freedom of conscience and belief. The existing laws are applied by the government according to the political and social context of each case. However, the state has continued to enforce its decisions from the 1980s to mandate the closure of most cafes and restaurants during Ramadan and has not taken steps to introduce clear legislation for Parliament to address the issue, leaving the controversy ambiguous and unresolved. Therefore, the public breaking of the Ramadan fast is not governed by any specific legal framework but rather subject to geographical and class considerations dictated by each social environment. In cities, especially in affluent neighborhoods, there is relative leniency toward the operation of public places for food and drink. In contrast, in rural areas, low-income neighborhoods and inner cities in the south and west of the country, the conservative social base demands stricter enforcement from authorities. In these areas, those who choose to break their fast often do so in secrecy to avoid stigma and ostracization from their families and tribal communities.

When Bourguiba first addressed Ramadan, he initiated a controversy over the holy month that encapsulated the political and religious debate with his opponents. It also deepened a cultural and regional division in the country and cast Tunisia and its people in a particular light for neighboring societies, an image that has not been dimmed by the passage of time or Bourguiba’s own death.

In the wake of President Kais Saied’s consolidation of power in Tunisia, ushering in a populist and authoritarian regime that tightly controls avenues of expression, Ramadan has emerged as a focal point of controversy and intellectual debate. This year, the holy month seems oddly subdued, devoid of the fiery debates that have traditionally characterized it. This tranquility, however, speaks volumes about the current state of political paralysis gripping both conservative and modernist factions in the country.

Since July 2021, Saied has effectively sidelined both conservative and modernist voices, monopolizing political discourse and public opinion. This dominance has cast a shadow over the usual fervor of Ramadan debates, marking a stark departure from the norm. One could attribute this calm to Saied’s conservative inclinations, which favor a more subdued public sphere. Alternatively, it may stem from the harsh economic realities facing Tunisians, including soaring living costs and widespread financial strain. As citizens grapple with economic hardship, the luxury of debating Ramadan rituals takes a back seat to more pressing concerns.

The subdued nature of this year’s Ramadan reflects not only the grip of political stagnation but also the harsh realities of everyday life for Tunisians. As the nation contends with its sociopolitical landscape, the absence of fervent Ramadan debates serves as a poignant reminder of the challenges facing its people.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.