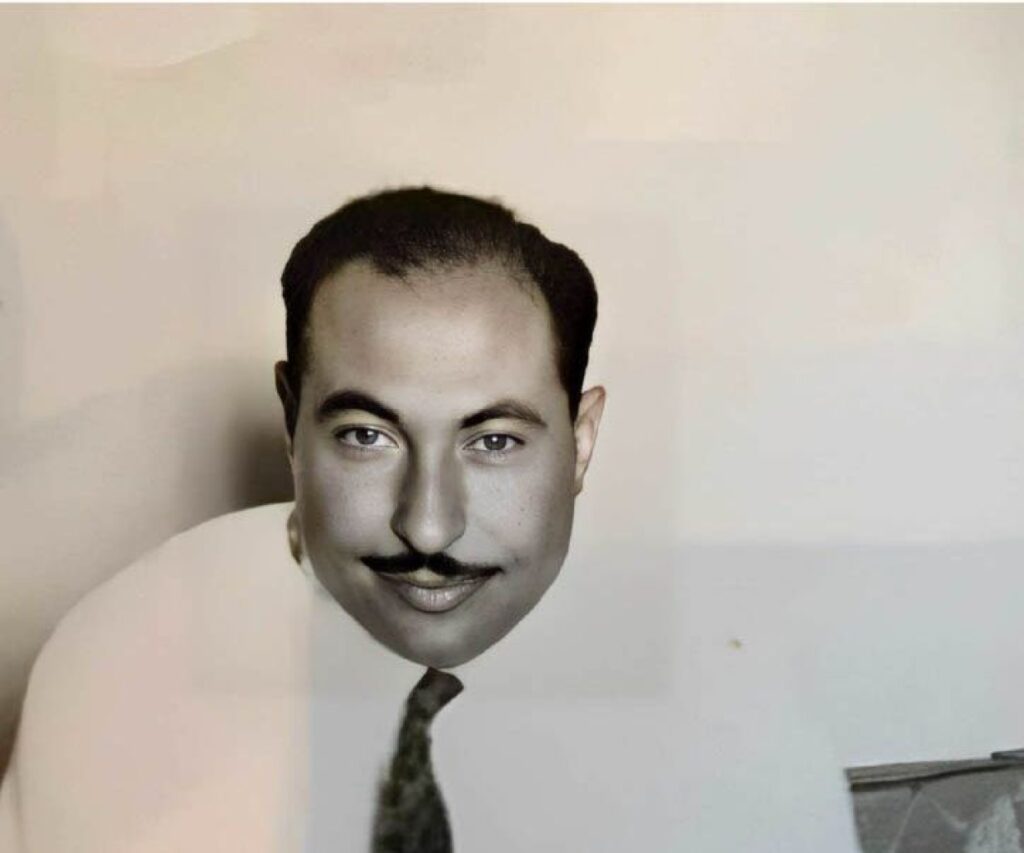

The morning of Aug. 29, 1960, began as every Monday did for Jordanian Prime Minister Hazzaa al-Majali. In his second-floor office in downtown Amman, the 42-year-old former lawyer held an open court, where anyone from senior officials to ordinary members of the public could show up for an audience, at which he would hear their petitions and try to resolve their problems.

Shortly before noon, he asked a young aide named Zaid al-Rifai — who would be prime minister himself in years to come — to fetch a file from elsewhere in the building. Rifai asked if he could have a cup of coffee first. To his mild annoyance, the premier insisted he leave the coffee till after he brought the file. As fate would have it, his demand spared the young man’s life.

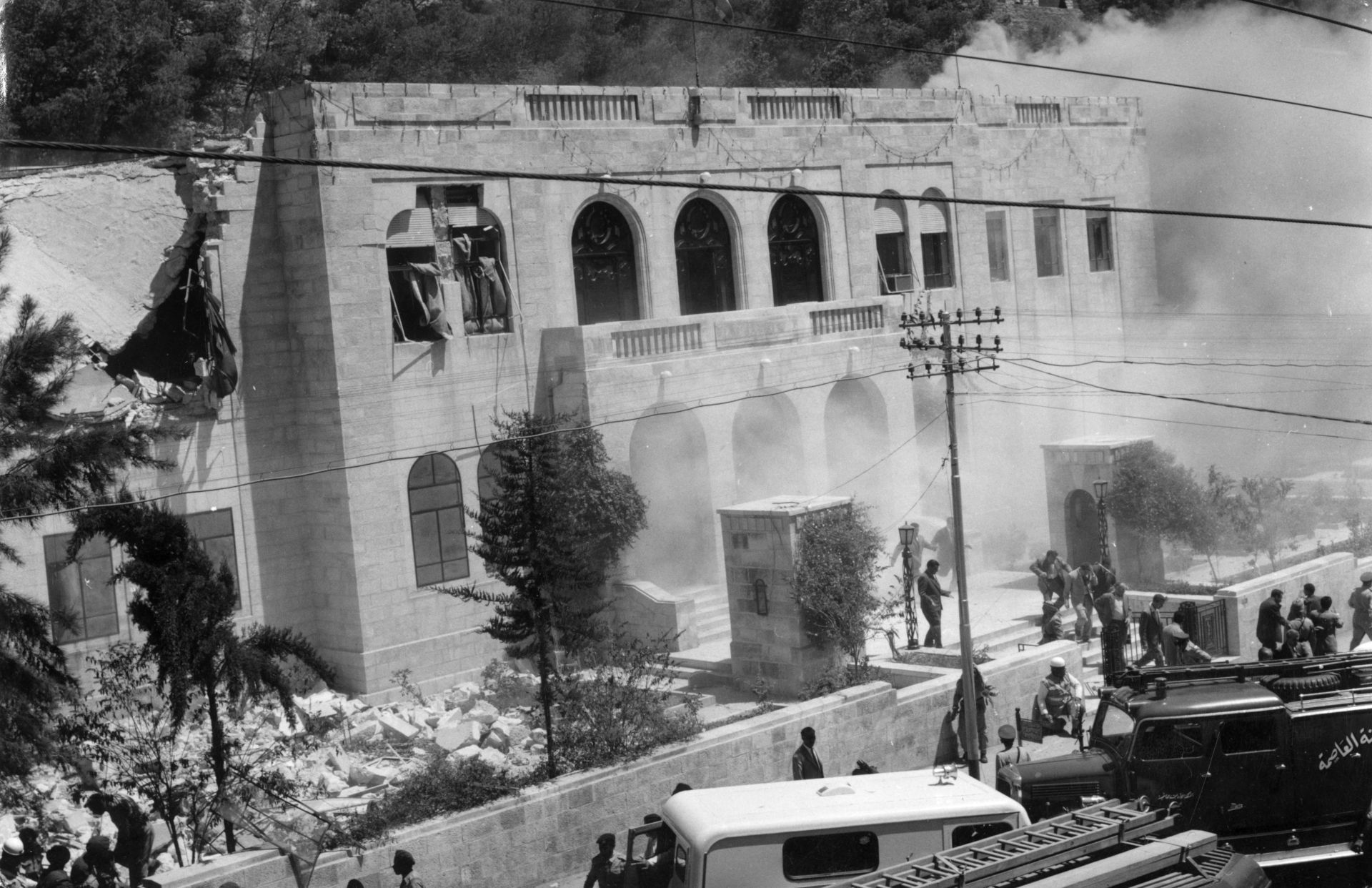

Moments after Rifai departed, Majali opened a drawer under his desk, triggering a concealed explosive device that detonated, killing him instantly. Seconds later, another bomb went off on the other side of the room, killing all but one of those present. The lone survivor, Abd al-Hamid al-Majali, had been standing at the moment of the first blast by a window, through which he was thrown by the force. By the time the second bomb blew, he was already outside the building, hurtling toward the ground below.

The twin blasts ripped out the walls of the office, caving in the roof. It would take three hours for the prime minister’s body to be dug out of the rubble.

Yet the carnage wasn’t over. On hearing the news, Jordan’s 24-year-old King Hussein raced to the scene, where he was prevented from approaching the building by the army’s commander in chief, who insisted the risk to his security was too great. The monarch retorted that no one had the authority to stop him. As the pair were arguing, a third explosion detonated at the building’s entrance, killing yet more victims. In all, 11 lives were taken by the three blasts, and 85 more people were injured. Aside from the premier, the dead ranged from an undersecretary for foreign affairs to a Palestinian refugee child. The sovereign himself had very nearly been among them.

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan was no stranger to assassinations. No less a figure than its first king, Abdallah I, had been shot dead in the head at point-blank range in 1951, at the entrance to Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa Mosque, with his 15-year-old grandson and future successor Hussein standing beside him.

Yet the killing of Majali was unprecedented in style and scale. It was the first time Jordan had witnessed a mass-casualty bombing that took the lives of innocent civilians along with senior statesmen. King Hussein called it “the worst outrage in the history of Jordan.” So appalled was he by the murder of “one of Jordan’s greatest patriots and one of my firmest friends” that he ordered three army brigades to mobilize on his northern border, in preparation for an attack on the prime suspects: his neighbors in Syria. It took the combined efforts of both Britain and the United States to persuade the enraged monarch to reconsider.

Rash the young Hussein may have been, but he was not wrong about the identity of the culprits. The blasts were the work of the United Arab Republic (UAR), a new state formed in 1958 by the union of Egypt with Syria and led by the iconic Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. The creation of this state precipitated — among many other things — a vicious downward spiral in relations between Nasser and Hussein. Jordan’s monarch saw the UAR as an aggressive and expansionist bully, bent on undermining his rule and, ultimately, toppling his throne so as to annex Jordan as another “province” of the unified superstate. He grew further convinced of this throughout the course of 1958 when, after watching the UAR sponsor an armed rebellion against the government in Lebanon, it then celebrated a gory military coup in Baghdad in July, during which the Iraqi royal family — headed by Hussein’s cousin and childhood friend, King Faysal II — were gunned down in cold blood, their corpses paraded and mutilated in the streets. That a similar scene would soon play out in Jordan’s own capital was not just Hussein’s fear; it was considered almost inevitable by most observers from Beirut to Foggy Bottom.

“However much one may admire the courage of this lonely young king,” said the British diplomat Anthony Nutting that month, “it is difficult to avoid the conclusion his days are numbered.”

For his part, Nasser did little to dispel these concerns. In a speech on July 18, 1958, just four days after the Iraqi coup, he vowed that the “banner of freedom” that had been raised in Baghdad would soon be hoisted above Amman too. In another speech four days later, he attacked Hussein by name, blasting him for soliciting British military support in the wake of the Baghdad coup, drawing a pointed comparison with the king’s assassinated grandfather, who had long been a British ally:

The king of Jordan [has] sided with imperialism. … What is Hussein doing today, my brothers? What is he doing in his fortress in Amman? He says he is “continuing the mission”; what mission is Hussein continuing today? The mission of King Abdallah, who betrayed us in 1948. Today, Hussein — my brothers — continues the mission of his grandfather King Abdallah in 1948, who deceived us, and deceived the Arabs everywhere. …

Today — my brothers — there is treason and occupation in Jordan, [but] the treason shall end, and the occupation shall end, and the people of Jordan shall be victorious.

By the time Majali was appointed prime minister in May 1959, the hostility between Cairo and Amman was at its peak. Two months earlier, King Hussein had charged that his army chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Sadiq al-Sharaa, was plotting a military coup against him, backed by the UAR. Shortly before that, the king alleged that UAR fighter pilots had tried to kill him by diving at his plane in the skies above Damascus while he was en route to Cyprus. Further attempts on his life around this time, according to his memoir, included acid in his nasal drops and a failed effort to poison his food.

“So cunning and varied and constant have been the plots against my person that sometimes I feel like the central character in a detective novel,” he wrote.

It was, indeed, precisely because the times were so fraught that Hussein felt the need to call on Majali — the son of a leading tribe in Karak in the monarchist hinterland east of the Dead Sea — whose loyalty to the Hashemite crown was beyond question. (Another prominent Majali was the premier’s brother-in-law, Field Marshal Habis al-Majali, chief commander of the armed forces and a pillar of the military since the kingdom’s establishment in 1946.) In Hussein’s words, Majali was “a man of courage, not afraid to shoulder responsibility.”

He could certainly have held few illusions about the dangers of the job. In March 1960, Jordan’s security forces arrested two people on charges of entering the country from Syria with the intention of assassinating Majali. Further plots of this kind would follow. Meanwhile, Nasser was stepping up his rhetorical attacks on Hussein, returning to the theme of his grandfather in a speech in June 1960, implying none too subtly that the king would meet the same “certain fate”:

The servants of imperialism may be able to go on a little longer, but where is their escape from their certain fate? The fate of … King Abdallah; where is the escape from that fate? The people — my brother citizens — shall be victorious, and shall eliminate the servants of imperialism, just as they eliminated their grandfathers before them.

When another attempt on Majali’s life was foiled in July 1960, he was advised to take greater security precautions and limit the number of visitors to his office. According to Hussein, he paid no heed.

One month later, he was dead.

On the last night of Majali’s life — Aug. 28, 1960 — two men named Shaker al-Dabbas and Kamal Shamut sneaked into his office and planted the explosives that would detonate the following morning. They then raced to Jordan’s northern border and crossed it. By the time the bombs went off, they were already on UAR soil.

The men had not acted alone. They had been tasked with their mission by a notorious military intelligence bureau in Damascus headed by Nasser’s Syrian security tsar, Col. Abd al-Hamid al-Sarraj. Having built a reputation since the mid-1950s for ruthless efficiency — as well as extraordinary violence — Sarraj was appointed interior minister of the Syrian “province” upon the creation of the UAR in 1958. In this capacity, he directed many of the union’s bloodiest interventions around the region, from the insurrection and bombing campaign in Lebanon to a deadly coup attempt in Mosul, Iraq, in 1959. That he was also behind the Majali assassination was confirmed by his colleague, Sami Jumaa, who boasted in his memoir that the operation demonstrated the “long arms” of the bureau. According to Salah Nasr, then chief of intelligence in Cairo, Nasser was at his beach house outside Alexandria meeting with Sarraj when news arrived of Majali’s killing. Nasser’s response was to reward Sarraj with a promotion that made him the most powerful man in Syria after Nasser himself.

In December 1960, Jordan’s State Security Court sentenced 11 men to death for the crime, among them (in absentia) the bombers al-Dabbas and Shamut and another of Sarraj’s colleagues in Damascus, Col. Burhan Adham. In Amman in 2021, while researching for a book on the Nasser era, I met Majali’s son, Gen. Hussein al-Majali — a senior official in his own right, who has served variously as Jordan’s interior minister, director of public security, commander of the royal guard, head of King Hussein’s personal security detail and ambassador to Bahrain. I asked him whether it was possible to see any documents from the official investigation into his father’s assassination, to shed light on how the court had arrived at its guilty verdict against the 11 accused. He replied that even he was not privy to that information. There are, he said, two highly classified folders held by the Criminal Information Department of Jordan’s Public Security Directorate, which he himself headed from 2010 to 2013. One of these folders concerns the assassination of King Abdallah I (great-grandfather of the present king); the second, that of Hazzaa al-Majali.

“They’re two huge files,” he said over coffee in his modest and tidy office, where a portrait of the late King Hussein still hung on the wall next to contemporary artworks depicting downtown Amman. “State secrets … I saw the two files, but I never dared to open them.”

Of the 11 sentenced to death, only four were in custody. They were promptly and publicly hanged in the courtyard of the Grand Husseini Mosque in the center of the capital. The other seven remained at large, some — including the bombers — offered asylum in Egypt for the rest of their lives. Al-Dabbas reportedly died in Cairo in 2021, at the age of 84.

Sarraj, too, went on to live for decades in Cairo as a fugitive from justice. When the UAR collapsed in 1961 and Syria became an independent republic once more, the new authorities in Damascus threw him in prison. He was smuggled out of his cell the following year, however, in an audacious breakout assisted by powerful friends of Nasser’s in Lebanon, including President Fouad Chehab and the warlord Kamal Jumblatt. After crossing the rugged Syrian-Lebanese border zone on camelback and spending a night as Jumblatt’s guest in his mountain palace, Sarraj was driven from Beirut in a Lebanese army jeep by the Lebanese military intelligence officer (and later interior minister) Sami al-Khatib to the airport, where he boarded a waiting plane to Cairo.

Arriving in the Egyptian capital, Sarraj was publicly received by a beaming Nasser, who employed him as an “adviser” for years thereafter — years that were not devoid of further killings bearing Sarraj’s fingerprints, like that of the Lebanese journalist Kamel Mrowa in 1966. Sarraj eventually died in Cairo in 2013, having given almost no press interviews in his 51 years of exile, loyally consigning most of his — and Nasser’s — secrets to the silence of the grave.

What is the historical significance of the Majali assassination? If it was intended to strengthen the UAR at the expense of Jordan’s monarchy, it clearly failed: The union disintegrated the following year, while today, six decades on, the Hashemite kingdom remains. Hussein himself stayed on the throne for 46 years until dying of natural causes in 1999, leaving the crown to his son.

Beyond Jordan, Majali’s killing may be seen as part of a series of related events that heralded darker days ahead for the region as a whole.

From the 1956 invasion of Egypt by Britain, France and Israel to the multiple coups in Iraq and Syria to Egypt’s own war in Yemen from 1962 to ’67 and more, this was a time of steadily mounting violence in Arab politics, as prior norms of comparative comity were cast aside and each new milestone of brutality spurred others to exceed it. The 1958 bloodshed in Lebanon, for instance, marked “the first major breakdown in political order after nearly a century of relative stability,” in the words of the Lebanese sociologist Samir Khalaf.

The Majali killing was neither the first nor the bloodiest of these events, but it was an important — and often overlooked — link in the same chain of violent episodes, all connected to one extent or another, as ideologies competed and countries were remade. The heavy legacy of these deeds is felt to this day.

The same torture methods developed in Sarraj’s dungeons in the 1950s continue to be used on political prisoners in Syria today. Many more prime ministers and other politicians have since been assassinated by bombs, as the Lebanese know better than most. Military officers continue to inflict horrors on vast numbers of Egyptians, Sudanese and Libyans, while murderous militias are the bane of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and beyond.

Millions of Arabs still live now in the world created by those responsible for the upheavals of the 1950s and ‘60s — some of whom were the very men who killed Majali.

Parts of this essay were adapted from the author’s recent book, “We Are Your Soldiers: How Gamal Abdel Nasser Remade the Arab World,” published in the U.S. and Canada by W. W. Norton and elsewhere by Simon & Schuster.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.