On Nov. 2, the Palestinian militant group Hamas declared that its fighters had launched 12 rockets at the Israeli border city of Kiryat Shmona from neighboring Lebanon. The strike, which wounded two and set cars ablaze on a commercial street, came four days after a similar attack in which the group said it had fired 16 rockets at northern Israel from southern Lebanon. That same day, Hamas staged a rare demonstration in the center of the Lebanese capital, Beirut, at which hundreds waved its flags and proclaimed support for its paramilitary wing, known as the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades. Some attendees, including young children, carried mock models of Hamas missiles.

Nor was that the first time Hamas had announced attacks on Israel from Lebanese territory since its stunning rampage across southern Israel on Oct. 7. Ten days earlier, on Oct. 19, the group proclaimed it had fired 30 rockets at the towns of Nahariya and Shlomi in the Galilee. It has launched other rockets at the Golan Heights and, on Oct. 14, attempted an entry into northern Israel near the border community of Margaliot, which was thwarted by an Israeli drone strike, killing three Hamas fighters.

This unusually prominent and visible role played by Hamas and other Palestinian factions in the recent fighting in Lebanon has raised fears in the country of a repeat of a dark chapter in its history, when clashes in the 1960s and ‘70s between Palestinian militants and Israel on Lebanese soil precipitated a wider conflict, roping in Lebanese armed groups too, culminating in the ruinous civil war from 1975 to 1990, from which the small Mediterranean nation has never fully recovered.

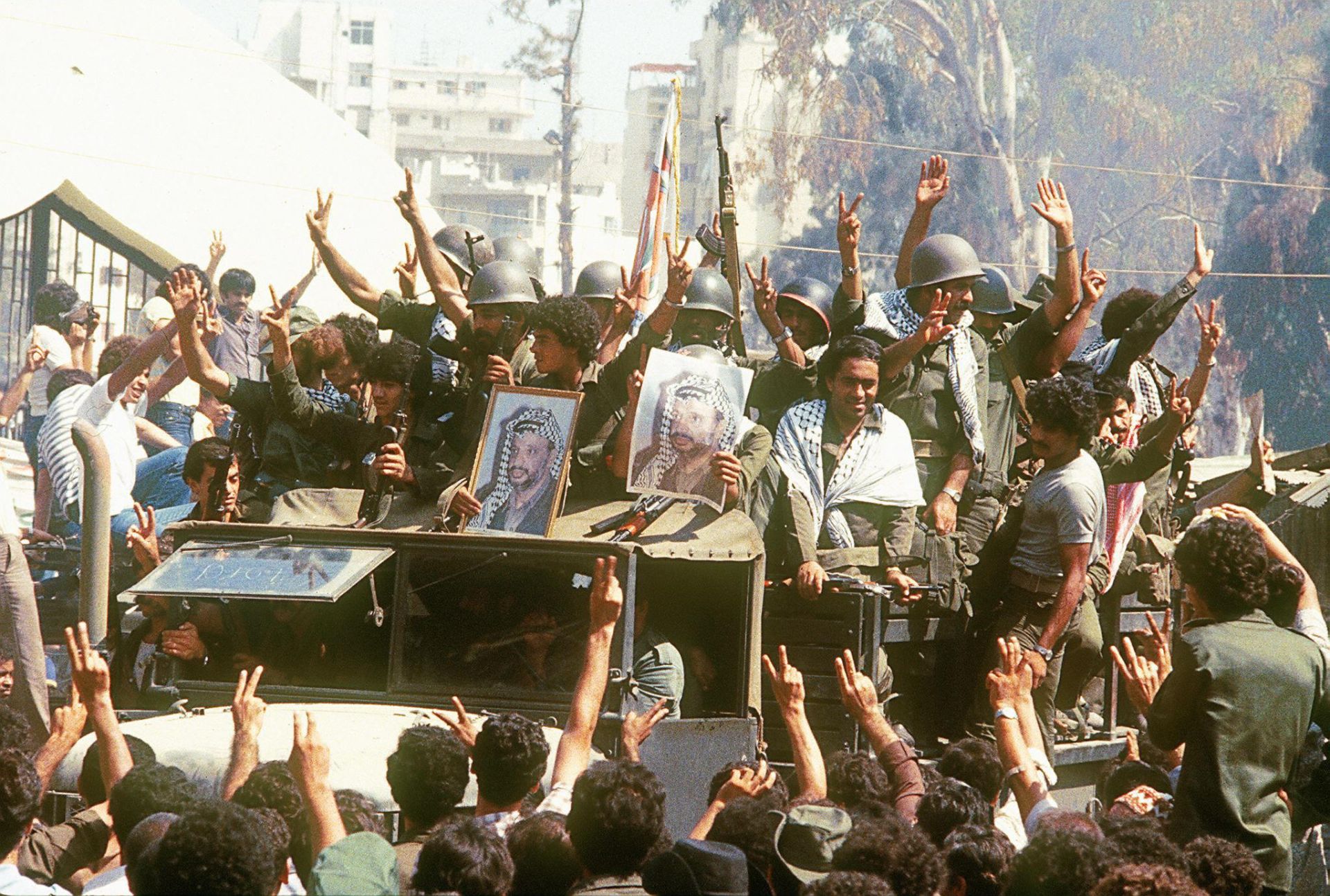

“We do not want to repeat the experience of Fatahland,” said Gebran Bassil, the head of a large political party, the Free Patriotic Movement, referring to the period when the late PLO leader Yasser Arafat’s Fatah militia controlled much of southern Lebanon. On X, formerly known as Twitter, the Lebanese journalist Yumna Fawaz put it more bluntly to her 162,000 followers on Oct. 29: “Hamas has no right to use Lebanese territory.”

Already, well before the October violence, concerns had been mounting in Lebanon about the growing presence and shifting behavior of Palestinian militants in the country.

Lebanon has recently become home to a number of senior Hamas officials who had previously been based in Qatar and Turkey. The country also now hosts the leader of another Palestinian militia, known as Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), which has also taken part in the recent fighting. In 2020, Hamas’ leader, Ismail Haniyeh, paid a much-publicized visit to Lebanon, touring the country’s Palestinian refugee camps, in what some Lebanese took as a provocative gesture. After days of deadly gun battles inside Lebanon’s largest camp in the summer of 2023, the Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati decried what he called the Palestinian factions’ “flagrant violation of Lebanese sovereignty,” saying it was “unacceptable” for the militants “to terrify the Lebanese.”

Much of this new dynamic is thought to be linked to a change at the helm in Gaza in 2017, when Yahya al-Sinwar — a ruthless character close to Iran — took over as Hamas’ leader in the strip. Under Sinwar, Hamas has mended fences with Lebanon’s Hezbollah as well as Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, both of whom it had previously clashed with over events in Syria. As hatchets were buried and old camaraderies restored, there was warm talk in pro-Iran circles of a “unity of battlefields,” meaning that any attack on one member of the club (such as Hamas in Gaza) would be taken as an attack on all. For Hamas and other Palestinian factions in Lebanon specifically, this meant being permitted — even expected — to take a more active part in combat against Israel than had previously been the norm.

In late October, reports circulated that the entire Hamas leadership in Gaza may be relocated to Lebanon, as part of a larger deal to end the fighting. Though far from confirmed, the mere suggestion was enough to cause alarm on Lebanese social media.

“Worst idea ever,” wrote the Lebanese journalist and author Kim Ghattas on X. “Whoever is floating this hasn’t thought it [through], hasn’t read history, frankly doesn’t care about the region.”

It would be “an epic disaster for Lebanon if true,” concurred the blogger Mustapha Hamoui.

As the Lebanese know all too well, there is ample precedent for “epic disasters” of this kind. Lebanon’s atrocious civil war — which killed an estimated 150,000 out of a population then numbering less than 3 million — remains within the living memory of every Lebanese over the age of about 36. And if there is any one phrase that serves as a byword for the diplomatic folly that set the country on its path to doom, it is “the Cairo Agreement” — signed on this day 54 years ago, in 1969. So notorious are the words that it sufficed for a Lebanese analyst on X to describe the Hamas relocation proposal as tantamount to “another Cairo Agreement in the making” for every Lebanese reader of his words to grasp the danger at hand.

What, then, was the Cairo Agreement?

Until the summer of 1967, Palestinian militancy had been a marginal phenomenon in Arab affairs. Since the establishment of Israel two decades earlier, the understanding had been that the task of fighting it fell to the regular armies of the three largest states on its borders: Egypt, Jordan and Syria. Armed Palestinian factions did exist — the PLO had been created in 1964 — but such operations as they conducted were largely ineffectual, and few if any observers deemed them an existential threat to Israel.

That all changed in one seismic week in June 1967, when Israel defeated the armed forces of Egypt, Jordan and Syria combined in the span of six days. The Palestinians could hardly be expected to continue pinning their national hopes on these armies, which now lay in ruin. Instead, they sought to take their destiny into their own hands — and the Arab states were happy to oblige, quietly relieved to be unburdened of the daunting task of liberating Jerusalem themselves.

With its large Palestinian refugee population and 75-mile land border with Israel, Lebanon thus found itself a main theater of the Arab-Israeli conflict in a way it had never been before. From the rolling green hills of its southern border zone, extending from the foot of Mount Hermon to the Mediterranean, Palestinian guerrillas began staging small-scale strikes on the Galilee. In Beirut, radical groups like the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine started planning and launching the dramatic campaign of international plane hijackings and other attacks that would seize the world’s attention into the 1970s.

Israel was swift and severe in responding. One of the more spectacular early incidents came on Dec. 28, 1968, when 66 Israeli commandos — among them a 19-year-old Benjamin Netanyahu, now Israel’s prime minister — descended by helicopter on Beirut’s airport and blew up over a dozen civilian aircraft belonging to Lebanon’s national carrier, Middle East Airlines. The assault came in response to a Palestinian attack on an Israeli El Al Boeing 707 at Athens airport two days earlier, in which one Israeli was killed.

Instability in the country only grew thereafter. Attempts by the Lebanese authorities to constrain the Palestinian militants led to armed clashes between the two. Demonstrations in support of the Palestinians in Beirut, Sidon and elsewhere on April 23, 1969, turned deadly when security forces opened fire on the crowds, killing 20. The next day, Lebanese Prime Minister Rashid Karami resigned in protest, though he was persuaded to stay on and form a new cabinet. Subsequent months witnessed a profound deterioration on all fronts. In August, deadly clashes broke out between Lebanese security forces and Palestinian guerrillas in the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp in northern Lebanon. The following month, the Lebanese army, police and military intelligence were forcibly evicted from Palestinian camps across the country. Meanwhile, Israel kept up its own attacks in parallel, launching another commando raid inside Lebanese territory that same month. October saw fierce gun battles between Lebanese and Palestinian forces all across Lebanon, from the far north to the deep south. Matters came to a bloody head when the Lebanese army besieged a Palestinian guerrilla unit near the southern border and killed 16.

Lebanese President Charles Helou — a weak leader with no popular base — had reached an impasse. He was powerless to restore order or bring the violence to an end. His prime minister-designate, Karami, still hadn’t formed his new cabinet, and now said he would not do so unless and until an agreement was negotiated with the PLO to legitimate and regulate its armed presence and activities. In this, Karami had the firm support of Lebanon’s Muslim political elites, which meant — by the quirks of Lebanon’s sectarian power-sharing customs — that the (Christian) Helou could not appoint an alternative premier without sparking yet another major crisis. Paralyzed and wholly out of his depth, Helou turned in desperation to the one man who commanded sufficient authority over all concerned to bring the situation under control: Egypt’s iconic President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Ever since coming to power in a 1952 military coup, Nasser had towered over Palestinian politics no less than he had all other Arab affairs. Cairo had been home to most of the key Palestinian civil-society groups of the 1950s and early ’60s, such as the Palestine Students Union — headed by a certain Yasser Arafat from 1952 to 1956 — and the leading Palestinian workers’ and women’s unions. It was Nasser who had summoned the Arab leaders to Alexandria in September 1964 to badger them into approving the establishment of the PLO, which was at first little more than another outlet of Nasserist influence. The organization was funded, trained and equipped by Egypt, which also hosted its radio station, Sawt Filastin (“the Voice of Palestine”). When, after 1967, the more militant Arafat moved to supplant the PLO’s discredited head, Ahmad al-Shuqayri, Nasser gave the move his blessing. Arafat became Nasser’s protege just as his predecessor had been, enjoying all the perks and privileges that came with the patronage of the godfather of Arab politics. It was natural, then, that when Nasser offered to help Lebanon’s beleaguered Helou reach a modus vivendi with Arafat, Helou hastened to accept — even though it meant doing so from a position of all-too-obvious weakness.

On Oct. 28, 1969, Helou sent a delegation to Cairo, led by Lebanon’s army commander, Gen. Emile Bustani, to meet with Arafat and Egyptian officials representing Nasser. It had actually been Premier Designate Karami who was supposed to head the delegation, with Bustani merely advising him on military matters. Karami, however, failed to show up at Beirut airport at the agreed time. When Bustani told Helou he would leave if Karami didn’t appear, Helou replied that he had given Nasser a personal promise to reach a swift agreement with the Palestinians, imploring Bustani to take the lead himself. The general reluctantly acquiesced.

In a sign of what was to come, the Lebanese were greeted at Cairo airport by a rowdy pro-PLO demonstration staged by the Egyptian authorities, at which abuse was hurled at Lebanon’s government and army. Alone but for two Lebanese diplomats and an intelligence officer of staunch Nasserist inclinations named Sami al-Khatib, Bustani then had to face a scrum of top Egyptian officials, including War Minister Gen. Muhammad Fawzi; Foreign Minister Mahmud Riyadh; Nasser’s senior intelligence aide, Sami Sharaf; and Nasser’s personal representative, Hassan Sabri al-Kholi — to say nothing of Arafat and his own six-man entourage.

The Egyptians were by no means impartial mediators standing at equal distance from the Lebanese and Palestinians. They actively pushed Bustani and his colleagues to concede to Arafat’s demands. Foreign Minister Riyadh pressed the Lebanese to “take an active part in the resistance” against Israel. Kholi told them Syria’s president had assured him that an agreement to allow the PLO freedom of action in Lebanon would resolve Beirut’s problems with Damascus, which had closed its Lebanese border in protest at the bloodshed earlier in the month. Bustani was even personally received by Nasser. On Oct. 31, they met at the resplendent Qubba Palace, where the president buttered him up with friendly chatter before urging him to ensure that the negotiations succeeded. Egyptian pressure — which also included letters from Nasser to Helou — was decisive in pushing through the final agreement.

This document, aptly named the Cairo Agreement, was signed by Bustani and Arafat on Nov. 3, 1969, in the presence of Egypt’s Fawzi and Riyadh. Subsequently approved by the Lebanese Parliament, it was an accord quite unlike any other in the annals of international relations. Its terms formally awarded Palestinian militants the right to attack Israel from Lebanese territory, and to be assisted in the act by the Lebanese army, which pledged to facilitate the guerrillas’ movements and military supply lines. The Palestinians were further allowed to operate from fixed military bases in southern Lebanon and to exercise autonomous rule over the refugee camps, free of any official Lebanese state presence. In exchange for these extraordinary prerogatives, they undertook to maintain discipline and avoid interfering in Lebanese internal affairs.

If there was ever a Rubicon moment for Lebanon, it was this. No other single step did more to set the country on its descent into the civil war that would erupt six years later. The Cairo Agreement’s significance went well beyond merely granting the Palestinians free rein to hit Israel from Lebanon — seismic though that was in itself. The attacks to which the agreement gave official Lebanese endorsement brought punishing Israeli reprisals down on Palestinians and Lebanese alike. These in turn invited yet more guerrilla operations, in a classic vicious cycle, each round of which fueled growing Lebanese discomfort with the Palestinians’ armed activities.

Before long, hard-line Lebanese nationalists, most of them Christian, were building up their own militias in preparation for a showdown with the Palestinians to “liberate” what they now saw as their own occupied homeland. On the other side, largely Muslim Lebanese leftists and Arab nationalists used the cover of the Cairo Agreement to arm their own paramilitaries, with which they pledged to defend their Palestinian comrades. What had begun in the late 1960s as an Israeli-Palestinian quarrel had, by the early ’70s, metastasized into a three-way Israeli-Palestinian-Lebanese conflict, superimposed on top of Lebanon’s preexisting internal divisions, with a religious sectarian dimension to boot. By 1975, the country was a giant Mexican standoff, with tens of thousands of heavily armed gunmen on all sides raring to go. No group was above the fray: Even the tiny Armenian community, descended from refugees fleeing genocide at Turkish hands in 1915–16, acquired its own militia. The teeming tinderbox was ignited in April 1975, in an infernal blaze that would rage unextinguished until 1990.

Is history repeating itself today?

On the surface, there are some striking parallels with the late 1960s. Once again, Palestinian militants are launching attacks on northern Israel from southern Lebanon. Once again, they are given an apparent free hand to do so by the Lebanese army and security forces (despite the Cairo Agreement being formally annulled by the Lebanese Parliament in 1987). Once again, Israel is responding to the attacks with lethal violence inside Lebanese territory. Once again, a larger foreign power acts as the Palestinians’ patron and protector in Lebanon, obliging the Beirut authorities to accept their activities — this time not Nasser’s Egypt but Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s Iran. Once again, Lebanon’s streets witness demonstrations supportive of Palestinian armed groups and their operations. Once again, all of the above stokes disquiet among significant segments of the Lebanese population, not least the Christian community, raising the possibility of internal discord, with potential sectarian dimensions.

There are also crucial differences, however. In terms of size, strength, firepower and political weight in Lebanon, the Palestinian militias remain dwarfed by Hezbollah, which is the undisputed senior in the relationship, the host of the party at which Hamas and PIJ are merely guests. (It is bemusing to see the likes of the Free Patriotic Movement’s Bassil warn so darkly against another “Fatahland” while, in the same breath, singing the praises of Hezbollah, Fatah’s incomparably more formidable successor.) No one is in any doubt that the main threat to Israeli security in Lebanon today is posed by Hezbollah. The Palestinians are a sideshow.

Yet that could change, at least by degrees, in the coming months and years. It remains too soon to say with confidence how the present round of fighting will end, and how it will reshape the security and political environment across the Levant as a whole. But there is, as yet, no indication that the trend of the past few years — that of deepening integration among Hamas, Hezbollah and all members of Iran’s so-called Axis of Resistance — is set to reverse. This is not a state of affairs that inspires optimism about the prospects for long-term stability in Lebanon. The further the militants of Hamas, PIJ and others like them entrench themselves in the country, the lower the likelihood that the Lebanese can avoid a replay of the film they have already seen too many times before.

The above is in part adapted from the author’s forthcoming book, “We Are Your Soldiers: How Gamal Abdel Nasser Remade the Arab World,” copyright 2024 by Alex Rowell. Used with permission of the publishers, W. W. Norton & Co., Inc, and Simon & Schuster UK Ltd. All rights reserved.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.