In St. Philip parish, on the easternmost tip of Barbados, there is a small, one-room, yellow and green “musalla.” With chipped, white wooden shutters, the prayer space looks like a mix between a chattel house and a beach kiosk, with accents of Islamic architectural flair.

Said to have been built by a local Black convert by the name of Shihabuddin at the front of his family residence, the room can fit six, maybe seven prayer rugs. Alongside four mosques, an academy, a research institute and a school, Shihabuddin’s musalla continues to act as a site of community connection for Muslims in the Caribbean island nation, despite Shihabuddin’s passing.

When one thinks of global Islam’s “representative sites,” as literary scholar Aliyah Khan calls them, images of grand mosques and significant shrines in Saudi Arabia, Palestine, Mali or Pakistan might immediately come to mind. And well they should. Yet, to overlook places such as Shihabuddin’s musalla — and other Islamic centers across the Caribbean, Latin America, the U.S. and Canada — as nodes in Islam’s worldwide networks would be to do a vast disservice to the numerous Muslims who call the hemisphere home.

In particular, it would be to sideline the significance of Black Muslims like Shihabuddin.

Beginning with the first Muslim to arrive with the Spanish in the 16th century, Black Muslims have been part of the American story, navigating enslavement, inequality and numerous other misrepresentations and marginalizations in the region for 500 years.

Today, their enduring legacy influences tens of thousands of Muslims across the region and around the globe.

Thus, tracing stories like Shihabuddin’s over the past five centuries provides not only a richer appreciation of the American hemisphere’s history but also its contemporary relevance as part of a broader “Muslim world.”

The earliest Muslims came to the Americas in the 1500s as part of Spain’s colonial expeditions.

One of the first was Mustafa Zemmouri — or Estavenico. Enslaved by Spanish conquistador Andrés Dorantes de Carranza in 1522, he was forcibly brought along to serve as part of the fated Narváez expedition to colonize “la Florida.” Although enslaved, Estavenico was one of the first Africans to set foot in the Americas, going on to explore Florida, the Gulf Coast and eventually modern-day Mexico and New Mexico.

Despite his exploits, his vital importance in the expedition’s struggle to survive and his rightful place in history, Estavenico was enslaved. Indeed, in Laila Lalami’s fictional retelling of Estavenico’s American adventures, “The Moor’s Account,” enslavement is Estavenico’s greatest affliction. Amid conflict and disease, the threat of starvation and being lost on a strange continent, Estavenico’s greatest concern remains regaining his freedom and returning to Azemmour, Morocco, his home. In her novel, Lalami imagines how he was forced into hard labor, accused of being “a lazy Moor,” and beaten.

Fictional though Lalami’s representation may be, most of Americas’ first Muslims were also enslaved. The rapid colonization of conquered territories in the Americas and the acquisitional drive by those who colonized them precipitated a centuries-long trade in enslaved persons from West Africa that left a permanent imprint across the Atlantic world.

Ships would leave European ports such as Nantes and Bristol, pack their cargo holds with enslaved Africans from the Senegambia, Gold Coast and Central Africa, and arrive at American ports in Brazil and Barbados, St. Domingue (present-day Haiti) and South Carolina. Over time, the transatlantic trade in enslaved persons became the single largest coerced movement of people in the history of the world and left an indelible mark on the demographics and dynamics of the Americas.

In the words of historian Greg Grandin, this trade also served as the “back door” by which Islam arrived in the Americas. Although the exact number is not known, scholars estimate that from 4 to 20% of the roughly 12.5 million Africans enslaved in the Americas were Muslim. Once here, they became part of “New World” debates over identity, policy, and the ideals of empires and emerging nation-states. Ayla Amon, formerly of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, wrote, “African Muslims were caught in the middle of complicated social and legal attitudes from the very moment they landed” on American shores and came to play a remarkable part in creating America as we know it, mapping its cultural and political contours, and fighting against colonial rule.

Legal documents, slaveholders’ records and abiding cultural traditions point to African Muslims’ significant presence and ongoing influence across the hemisphere. Scholars have recently scoured these sources, revealing stories of resilience and resistance, creative adaptation and attentive conservation.

For example, it is well documented that a number of enslaved Africans were educated and literate in Arabic. Muhammad Kaba Saghanughu was one of them.

“Kaba” as he is often known, was forcibly brought to Jamaica in 1777. He was obliged to serve on the coffee estate of Spice Grove in Jamaica’s mountainous interior near the town of Mandeville, Manchester Parish. Although he later converted to Christianity and became a baptized member of the Moravian Mission Church — and his Arabic was not pristine — his writings reveal a man, and a community, committed to the preservation and passing on of Sufi prayers and rituals.

Individuals like Kaba, many of them holy men (“marabouts”) in West Africa, were also able to use their literacy and previous training in West African religious traditions to gain a semblance of success in the Americas’ plantation societies. Many were given leadership positions among their fellow captives and attempted to bring unity out of the miscellany that was created by the messy transatlantic trade in enslaved persons. This was no easy task, given the diversity of beliefs, practices and ethno-linguistic heritages the enslaved brought with them.

They used Arabic to reaffirm their faith, to plead to be returned to Africa, to condemn slavery and in some instances to gain their freedom, according to Amon. Others, who were not literate, brought a diverse set of Islamic ritual traditions prevalent in West Africa at the time. From the evidence we have, we know that enslaved Muslims prayed, worked, ate halal as best they could, resisted enslavement, and adapted to their new context. In multiple ways, they undermined the racist frames that supposed Africans were illiterate and uncultured.

Indeed, for all its devastating effects on human culture and society, slavery proved not only a disruptor of African culture and religion but also a catalyst for adaptation and transformation. Across the Americas, the religious traditions of the enslaved — including Islam, Yoruba, Akan and other African traditions — persisted through adaptation, secrecy and isolation, wrote historian Peter Manseau. Among them, practicing Muslims found a way to grasp agency in the midst of bondage, nourish and pass on a rich cultural history stretching back to the 8th century, and resist the larger systemic forces of oppression that impeded the free practice of their faith.

Some enslaved African Muslims used their literacy to directly resist their captivity, generate rebellion and lead their fellows in revolution.

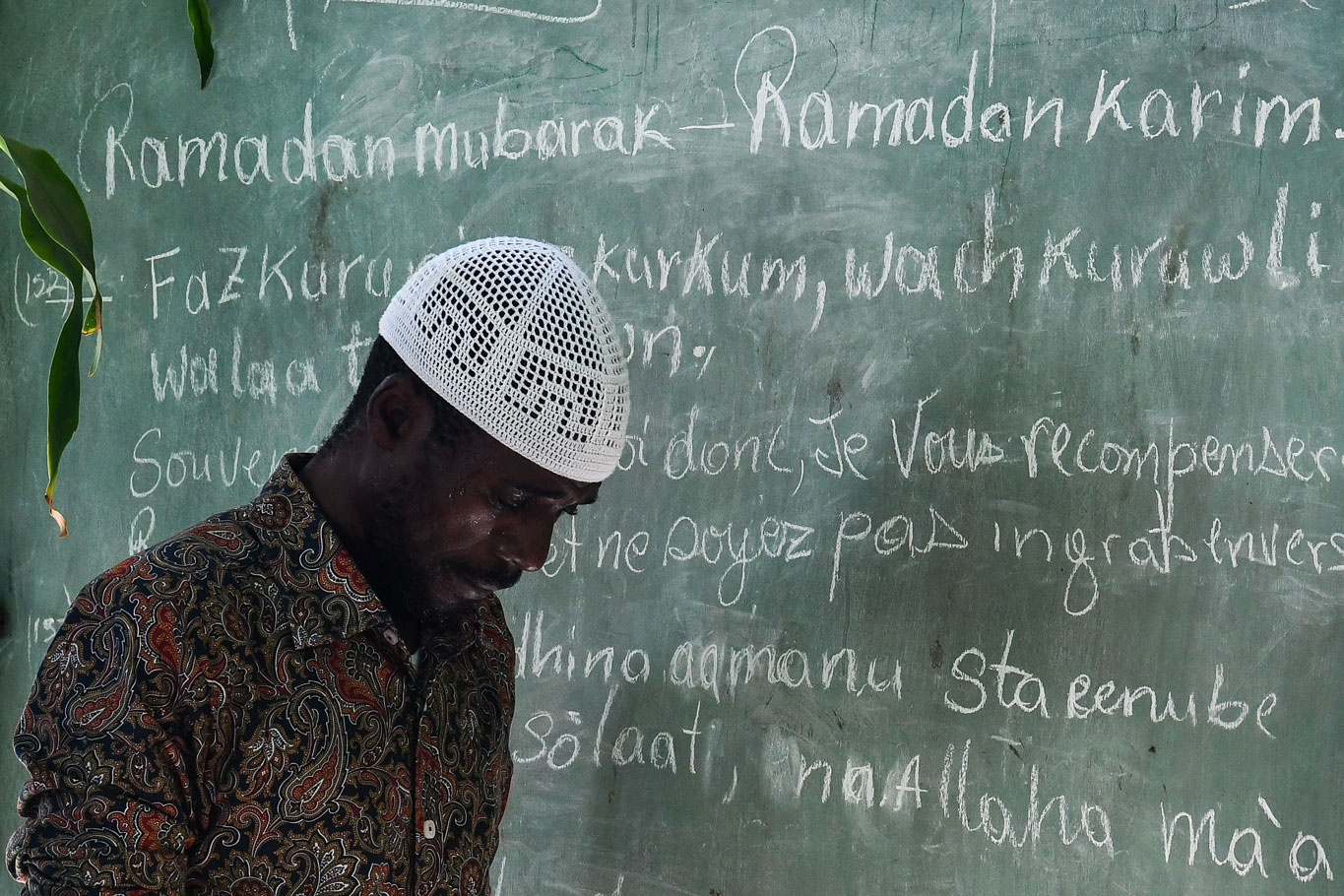

One such incident occurred on a Sunday during Ramadan in January 1835 in the city of Salvador de Bahia, Brazil. That day, a company of enslaved and free Africans rebelled. Inspired by a core group of Muslim leaders, the rebellion became known as the Mâle Revolt. Although the revolt was quickly quashed, its symbolic meaning endured. It remains an example of not only how Muslims could serve as leaders among the enslaved but also of their lasting relevance to Black people in the Americas resisting ongoing racism and structural oppression today.

African and African-descended Muslims did not kowtow, recede into the background as impotent subalterns or walk in step as the “well-behaved slave.” Instead, many became active agents in the shaping of the Americas through their leadership of fellow enslaved persons in rebellion against enslavement in Brazil (1813, 1826, 1827, 1828, 1830 and 1835), Puerto Rico (1527), and possibly in Haiti (1786). They also helped carve out spaces of refuge and resistance through the founding of maroon communities in Jamaica and Brazil.

Along the way, African and African-descended Muslims helped create common cause among the enslaved and the freed. Fear of their rebellions, as racially tinged as it was, also came to shape American politics and law as colonial powers sought to minimize their ability to disrupt the social and political order of the day. By leveraging their leadership and, as John Tofik Karam wrote, “mobilizing among enslaved subjects and against the prevailing status quo,” the subjugating context of their oppression not only shaped them but in turn led them to shape the New World by resisting it.

Unfortunately, as with other enslaved Africans, historian Allan Austin wrote, the vast majority of their names and narratives remain unknown to us in the historical record, obscured by the oppressive anonymity of their names on their supposed owners’ ignominious lists.

Nevertheless, Islamic practice and Muslim presence in the Americas faded by the end of the 19th century. As the Black community was not permitted to publicly practice or pass on the religion to their children or build infrastructure for the preservation of the faith, the explicit practice of Islam eventually disappeared. As historian Sylviane Diouf wrote, “in the Americas and the Caribbean, not one community currently practices Islam as passed on by preceding African generations.”

However, if Islam as a lived religion died out in the Americas, it was passed on in other ways through the influence of various cultural traditions still prevalent today. African-style Muslim amulets can still be found in places like Brazil. Arabic words made their way into music as far afield as Peru, Cuba, Georgia and Trinidad. Historian Michael Gomez even suggested that blues and jazz were influenced by West African Muslim musical styles and motifs; Islamic legacies have played an important role in shaping American rap music. Furthermore, Khan suggested that ancestral African Sufi tradition influenced contemporary Caribbean literary discourse through the likes of Muhammad Abdur-Rahman Slade, the popular and renowned Guyanese poet and actor.

Yet it is perhaps in the realm of religion that this legacy lives on most noticeably. Black Muslims in groups as diverse as the Moorish Science Temple, the Nation of Islam (NOI), the Five Percent Nation (FPN), Ahmadiyya communities, Sufi “turuq” and Sunni Muslim movements draw on the legacy of their enslaved antecedents to confirm their character as American Muslims, encourage others to convert and espouse the longevity of Islam in the Americas.

They also call on their enslaved Muslim forebears for inspiration and as a rallying cry against contemporary oppressions. Take, for example, Shihabuddin’s Muslim community in Barbados. With predominantly West Bengali and Afro-Barbadian roots, Muslims are still a largely unknown element in Barbados’ religious landscape and struggle to underscore that they are “Bajan” – of Barbados – over and against popular perceptions that they are foreign, different, and “Other.” And yet, with history that stretches back hundreds of years, Barbados’ Muslims feel “Bajan to the bone,” part of the very fabric of the nation.

Ako, an Afro-Barbadian Muslim, said that “as African people in the Caribbean, our identity was taken away from us. We have to go in search of our roots.” He believes this is especially important for young Black Muslims in the Caribbean. Ako elaborated: “If you look into the cultural background of our countries you can see the influence of African Muslims. They were here in Barbados. They were in Trinidad. Jamaica. Haiti. They were leaders. Influencers.”

Today, he sees many Afro-Barbadian youth losing their way and believes unearthing the deep roots of African Muslim legacy is a means of soothing the disquiet and focusing the rage against inequality abroad and at home. “If we are trying to break a cycle, we have to find our bearings,” Ako said. “We have to remember who we are.”

Alaina Morgan, historian of race, religion and politics, says that Muslims similar to Ako — in Trinidad and the Bahamas, Haiti and Puerto Rico — use ideas of Blackness and African Muslim legacies to build global anti-colonial and anti-imperial networks, past and present. Whether it be enslavement at the hands of European powers or the struggle for human rights or the contention that Black lives matter, African Muslim histories are a critical ingredient in the make-up of Black narratives across the hemisphere and beyond.

Although there may not be individuals who act as physical links between enslaved African Muslim communities and contemporary Black Muslim communities, there is a chain of inspiration, connection and shared vision that stretches back across the time and geographic boundaries.

This legacy and influence go beyond Black communities in the Americas and extends to other nodes in the transnational Black Muslim diaspora as well. While African-descended Muslims live in various societies, scholar Edward E. Curtis IV wrote, “they often live as Muslims in societies that are, to a greater or lesser degree, racist.”

Among Jamaicans and Trinidadians in the U.K., for example, the legacy of their forebears’ resistance to European colonialism and the racist practice of enslavement continue to reverberate and resonate with their contemporary experience. Muneera Rashida and Sukina Abdul Noor, who make up the U.K. hip-hop duo Poetic Pilgrimage, ride the ups and downs, the beats and drops of “their personal, spiritual and physical journey” as Jamaican Muslims through their music. They also find a voice to critique “both racism in the British context and the long history of European colonialism and neocolonialism,” wrote Curtis. For Poetic Pilgrimage, the deep legacy of resistance by enslaved African Muslims in Jamaica serves as a font of justice and liberation from which they draw to critique current structures of power they see as disenfranchising or unequal.

In this way, the memory of Islam in the Americas was never fully lost and never truly died out. Instead, through the stories of individuals like Estavenico and Kaba, Ako and Shihabuddin, Muneera and Sukina, we see how it has been transformed, not only surviving the Middle Passage and the passage of time but also thriving through new combinations, interpretations and manifestations.

That is why, along with Black Muslims across the world, it is important to re-encounter and recenter their stories. As we further explore their legacy, we might see how their centuries-long experience can help us better understand and address contemporary currents of Islamophobia, anti-Muslim bias and racism in the Americas.