The Canadian election in April, which led to Mark Carney’s Liberal Party forming a minority government, was widely understood as a repudiation of U.S. President Donald Trump’s antagonism toward Canada. Trump’s tariff regime and his frequent threats to make Canada “the 51st state” were the primary reasons Carney’s Liberal Party was able to pull off a stunning reversal of political fortune. Only a few months earlier, the opposing Conservative Party, led by Pierre Poilievre, had been far ahead in the polls.

Yet months after that victory, and despite rhetoric about putting “elbows up” in the wake of Trump’s political bluster, Carney has capitulated to him on various occasions, ostensibly in an effort to assuage tensions between the two countries. This has left many Canadians wondering if their national interests are truly being upheld, as boycotts of American products continue and economic and cultural resentment has calcified. A rift has emerged as anti-Americanism continues to fester among the populace, even as the government seeks new paths to the status quo.

What has been largely overlooked, though, is the long, colorful history of anti-American fervor in Canada. Trump did not “betray” his closest ally to the north, as Carney previously suggested; he simply reignited long-standing sentiments buried within both the American and Canadian psyches, but never far from the surface.

Trump’s threats are nothing new. Beginning in 1774 and into 1775, on the eve of the Revolutionary War, George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and other framers of the American republic plotted to colonize and occupy Canada, then fully under British control, as part of America’s emergence on the world stage, including through a failed siege of Quebec in October of 1775. As Washington wrote to “the inhabitants of Canada” in September of that year, “Come then, my Brethren, unite with us in an indissoluble Union, let us run together to the same Goal.” The British were not interested, and the nascent Canadians were generally still extremely loyal to the Crown.

Canadian anti-Americanism in the 19th century, then, arose from a legitimate fear of invasion. This resurfaced in the War of 1812, as America — now the United States — clashed with the British and their allies in British North America, or what would become Canada. At that point, whether the Americans truly intended to annex Canada or were simply using the threat as a tactic to pressure the British, they again carried out invasions of the territory. (Fun fact: One piece of territory, Machias Seal Island between the Gulf of Maine and the Bay of Fundy, remains disputed between Canada and the U.S. today.)

The Canadian War Museum, in its summary of the war, has an almost triumphant tone: “Canadians endured repeated invasions and occasional occupations, but each invasion ultimately ended with an American withdrawal.” The implied sentiment remains prominent in Canadian history textbooks and curricula, and major figures of that resistance remain some of Canada’s most admired and well-known historical figures, precisely due to their association with fighting back against the Americans, including Isaac Brock, a British general who secured the American surrender of Fort Detroit in 1812 (my hometown is named after him); Tecumseh, a Shawnee chief who opposed American expansionism and fought alongside Brock and others; Laura Secord, who walked 20 miles out of American territory to warn the British of an impending attack (a popular chocolate company is named after her); and Charles de Salaberry, who repelled an American invasion in Quebec, thereby becoming a folk hero in French Canada.

Canadians also suffer, it must be said, from a general feeling of always being in the shadow of the U.S., because Canada’s culture and economy exist downstream of its dominant neighbor. This has historically had an impact on attitudes about trade between the countries: Opening up to more trade risked allowing even more American influence. But repeatedly through the 20th century and into the 21st, if trade disputes were not stoking Canadian ire, America’s wars were doing so. Alignment during and after World War II is the exception. Beyond that, Canada has often turned against the U.S. in times of war, particularly with respect to Vietnam and Iraq.

Some of this is certainly bound up with a largely unearned sense of moral superiority. Canada, despite pushing its image as a polite “peacekeeping” nation, has been involved to varying extents in almost all of America’s wars. For instance, and perhaps most significantly, more than 40,000 troops in the Canadian Armed Forces fought in Afghanistan, and Canada also contributed to the 1991 Gulf War (including through bombing missions) and the Korean War, among other conflicts. Even during Vietnam, while Canadians themselves protested the war and their government refused to send troops, Canadian military bases were nevertheless used as testing grounds for Agent Orange.

In short, Canada has long struggled to find its own identity. As the historian and journalist Richard Gwyn put it in a 2008 lecture at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Toronto, “The awkward truth is that just about any description of Canadian identity has as its first line: ‘Canadians are Not-Americans.’” Gwyn noted how Canada’s sense of moral superiority as a supposedly peaceful and polite nation stretches back to the 19th century, when much of its self-image centered on the respectability of its small-c conservatism: Americans were seen as violent, genocidal and upheld slavery almost a full century longer than Canada. Canada’s confederation in 1867, spurred in part by economic vulnerability following Washington’s cancellation of the cross-border Reciprocity Treaty in 1866, brought together Canada’s provinces into one federation — the Dominion of Canada. According to Gwyn, this was brought about not only for economic reasons, but almost entirely because Canadians wanted once and for all to assert their non-Americanness.

In her 2009 book “Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media,” Chantal Allan argues that “if there has been one enduring and overriding fear among Canadians, it is that of annexation.” Trump’s bluster about turning Canada into the 51st American state, then, follows a long history of this kind of comment from Americans and bitter resentment from Canada as a result. This concern was common enough at the time of Canada’s confederation in 1867. As Allan points out, the Chicago Tribune in December of that year suggested, rather paternalistically, that if the newly minted, resource-heavy but backward-seeming Canadians were instead to become American, they would “add strength and stability to our government and institutions, and at the same time push themselves half a century ahead in all their industrial and commercial interests.” The next month, the Tribune dug the knife in deeper, suggesting that Canadians migrate to America to “better their condition” and “leave the Provinces to vegetate and decay, in sight of the universal prosperity and increase in every State on the opposite side of the lakes.”

In Canada during this period, attitudes were grave. In a famous 1865 speech during the confederation debates — a series of discussions in the Parliament of the Province of Canada, today Ontario and Quebec, about whether to join with the British colonies of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick — Thomas D’Arcy McGee, who fled from Ireland to the United States before moving to Canada and becoming a parliamentarian, said about the U.S.:

They coveted Florida, and seized it; they coveted Louisiana, and they purchased it; they coveted Texas, and stole it; and then they picked a quarrel with Mexico which ended by their getting California. … The acquisition of Canada was the first ambition of the American Confederacy, and never ceased to be so, when her troops were a handful and her navy scarce a squadron. Is it likely to be stopped now, when she counts her guns afloat by thousands and her troops by hundreds of thousands?

McGee was close to the man who would become Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. MacDonald, and they shared this view about the “risk of being swallowed up” by the U.S., and about the inadequacy of American republicanism when compared with British-style parliamentary democracy. This feeling would pervade the process of confederation and the years to come.

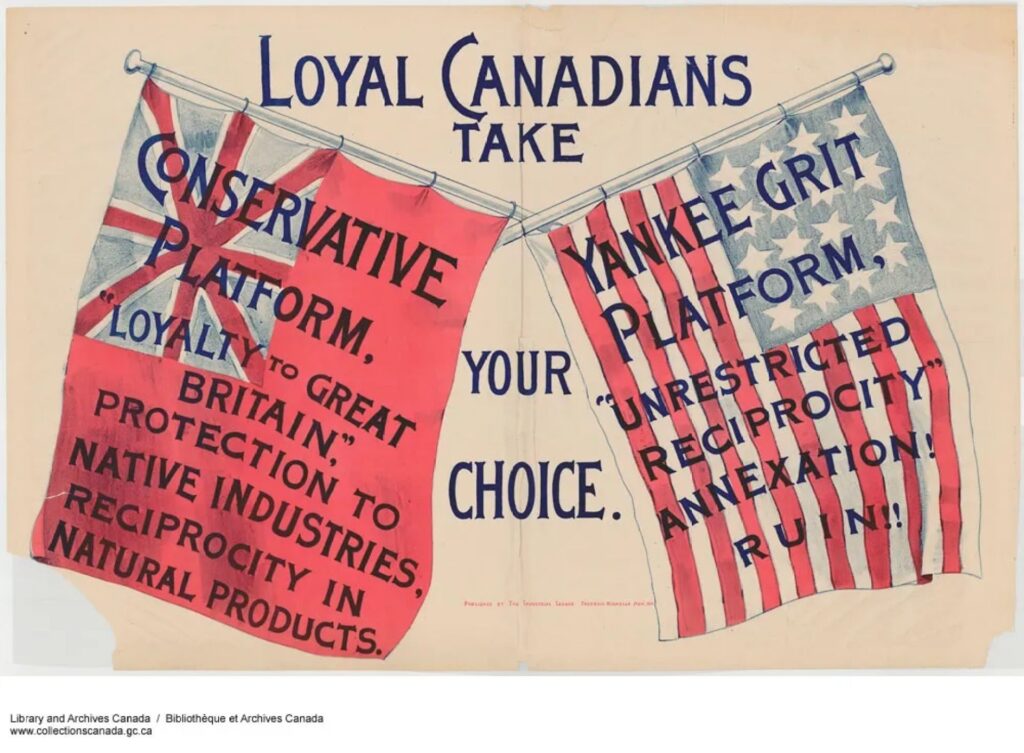

This was the state of affairs when Canada’s economy was still just emerging and good jobs were relatively scarce, but by the early 20th century, tensions were growing alongside Canadian trade and wealth. Perhaps the most significant antecedent to the current trade furor was in 1911, during debates over a new reciprocity agreement (what we would now call a free trade agreement) between the two countries, when Champ Clark, speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, declared: “I look forward to the time when the American flag will fly over every square foot of British North America up to the North Pole. The people of Canada are of our blood and language.”

Many Canadians took this as a direct call for annexation, which sparked outrage. The subsequent political fiasco, like today’s, helped swing that year’s federal election for Conservative Robert Borden, who campaigned hard against the trade agreement, which he argued would “Americanize” Canada. (Borden also sought to maintain Canada’s British ties, which were seen as necessary, both economically and culturally.) As Allan put it in “Bomb Canada”:

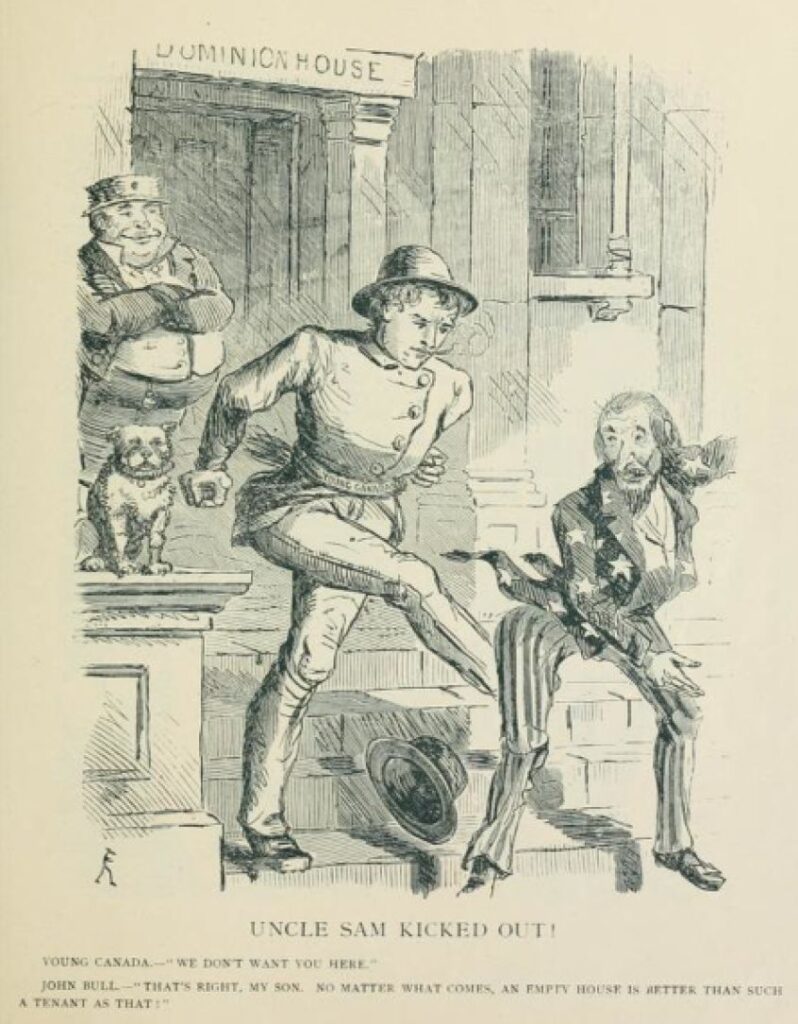

A correspondent in Ontario reported that hundreds of thousands of pamphlets containing extracts of the annexation speeches made in Congress were being handed out to newly arrived British immigrants and Canadians loyal to the British Empire. News dispatches from Montreal described the proliferation of anti-American cartoons in newsprint including one of a whisky bottle with the Stars and Stripes as its label and another of Americans rejoicing in Canada’s downfall.

And so, with Borden elected, the reciprocity agreement was dead. Some historians have seen this rejection of reciprocity as the country shooting itself in the foot, all because Canadians were so fiercely against being absorbed in any sense by the United States. Allan quotes The Oregonian newspaper, which put it succinctly, if rather petulantly, at the time: The agreement was rejected “because Canada does not like us, anyway.”

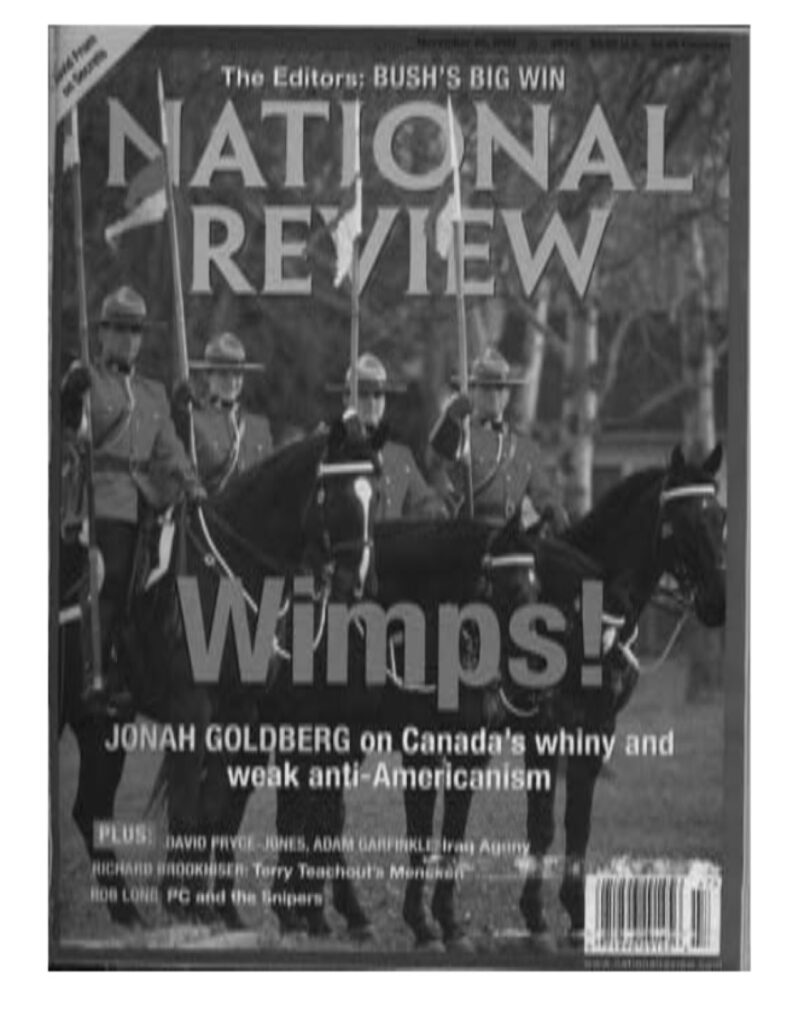

Canadians continued to feel this tension during the Cold War, particularly as the country chose to maintain trade relations with Cuba and the Soviet Union, much to the chagrin of the U.S. It blew up during the Vietnam War, as the government found ways to abet America’s war effort materially while, as Allan puts it, “maintaining its polished peacekeeper image,” and again during the American invasion of Iraq. In that case, as has been observed in 2025, Canadians booed “The Star-Spangled Banner” at hockey games while others burned the American flag, and many protest rallies were held against then-President George W. Bush during his visit to Ottawa in 2004.

Many historians and observers of U.S.-Canada relations have sought to diagnose the psychological factors behind the lingering anxiety between the two otherwise “best friend” nations, which often tout the fact that they share the world’s largest undefended border. Kim Richard Nossal, perhaps the leading scholar on Canada’s anti-Americanism, has noted that Canada is the only country in the world that “owes its existence to a conscious act of anti-Americanism” due to “the refusal by elites in the other British North American colonies [what we now refer to as Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick] to accept the invitation of the American revolutionaries to join in the new republican experiment.”

Interestingly, though, he describes most Canadian anti-Americanism as being “bland” and “low grade,” like an ambient undercurrent to the polity. That undercurrent, though, is routinely reawakened during high-pressure elections, through a dynamic Nossal describes as negatively impacting parties that either distance themselves too much from the U.S. in their proposals or are too closely aligned with the U.S. Either way, historically speaking, such parties typically lose out.

Long-lasting Canadian anti-Americanism, he continues, has largely been rendered in economic terms. Canadians generally accept, consciously or not, American culture (despite repeated attempts to shore up the value of Canadian art), so “Americanization” on that score is not an issue. On the other hand, the Americanization of the economy is a far more pressing existential threat. Again, this can be seen through Canada’s long-standing opposition to increased economic integration, which continued to permeate Canadian attitudes until a free trade agreement was finally reached in 1988. It’s worth remembering in the current political climate that this level of integration is relatively recent in the history of the two countries.

The famous 1988 Liberal Party election ad, “Border,” features an American man saying, “Since we’re talking about this free trade agreement, there’s one line I’d like to change,” before cutting to him erasing the Canada-U.S. border (since it’s “just getting in the way”). The Liberals would go on to lose that election, but their experience vying for Canadians’ votes highlights how conflicted the country is, not only about trade with the U.S., but more generally over Canada’s undeniable ties to the American economy.

Nossal identifies a form of Canadian anti-Americanism that is more latent and contingent, dependent on particular policies and people in the U.S. government — opposition to the Iraq war, say, or, later, to Trump’s presidency itself. In recent decades, this has led to anti-Americanism emerging during Canadian elections. The Liberal Party in particular, led by both Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin, was plagued by mini-scandals about their negative views on Bush and his policies.

Even so, Nossal argued in 2005 that a more generalized rejection of American-ness was gone from Canadian society:

The kind of anti-Americanism that had been so firmly entrenched in Canadian political culture—the opposition to being taken over or absorbed by the United States that had fuelled such sustained opposition to the forces of continentalism and economic integration, economic anti-Americanism—is indeed dead, at least for the moment.

Emphasis added — for obvious reasons.

The question then becomes: Is anti-Americanism a fad that erupts from time to time, or is it a core element of Canadian politics and identity?

To help articulate the lasting power of frequent flare-ups in anti-American sentiment, it’s worth considering the wide range of impacts they can have. Take the Vietnam War, when, as the Canadian historian J.L. Granatstein put it in his 1996 book “Yankee Go Home: Canadians and Anti-Americanism,” “The anti-war and the anti-American anger in Canada continued to grow slowly and to reinforce each other.”

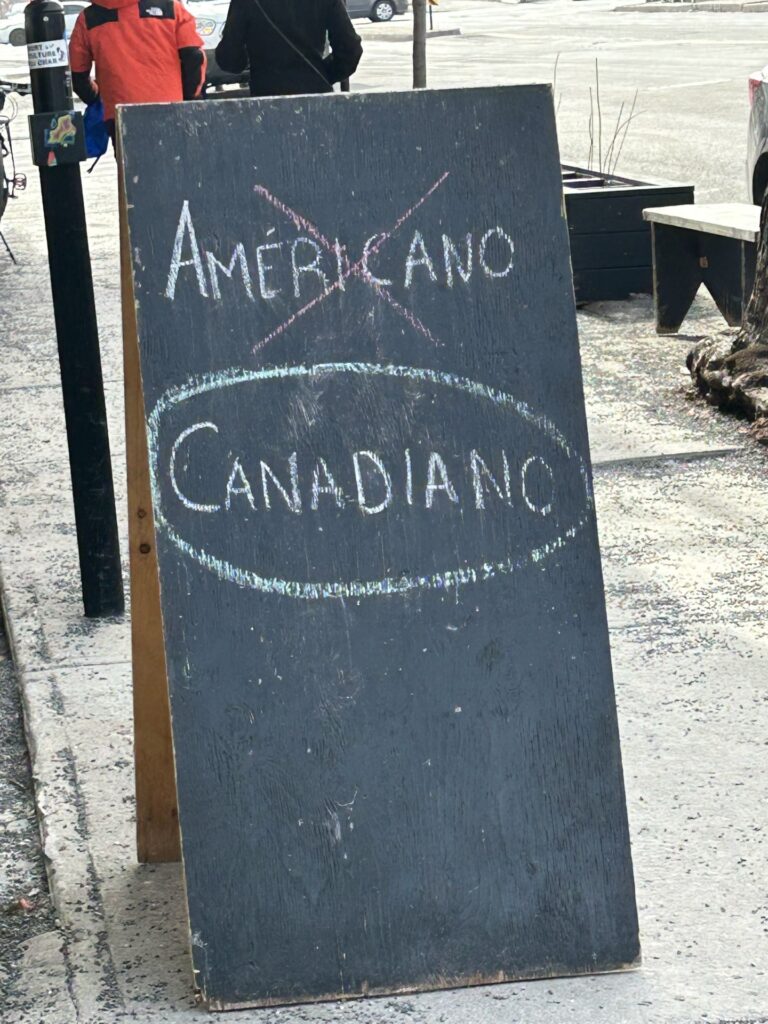

A study by Canadian English scholars Alison Borden, Alexandra Erath and Julie Yang, for example, showed that, amid heightened anti-American sentiment during Vietnam, Canadian English became more aligned than it already was with British English, adopting spellings like “colour” as yet another way to further distinguish Canadians from Americans. Today, Canadians are again using language, though perhaps more cheekily, to illustrate this distinction, with many cafes changing their coffee menus to replace Americanos with “Canadianos” — the better to avoid drinking such a Yankee beverage.

On the other hand, in 1988, political historians Charles F. Doran and James Patrick Sewell argued that while anti-Americanism was present in Canada, it was not a “core element of Canadian political culture.” Yet they note that anti-Americanism can still be politically useful in many cases: “Caricature of Americans and American policy, therefore, proves especially useful in Canada because it helps provide the cement to which Canadian politicians from time to time resort in order to keep the polity together.”

This truly was Trump’s gift to Carney and the Liberals. Doran and Sewell are not particularly off base, then, when they claim that “it seems that anti-Americanism occurs in Canada only when it is politically functional.” English and French Canada, for example, are seemingly always at odds, yet they temporarily set aside their differences when Quebec helped lead the Liberals to victory in the last election, proving that the one thing all Canadians can agree on is a resistance to becoming American. It’s even an easy selling point, as evidenced by the new slogan of the leading Canadian magazine Maclean’s: “Canada isn’t for sale. Maclean’s is. Subscribe today.”

As Norman Hillmer said of historian Frank Underhill, who famously called Canadians the world’s oldest continuing anti-Americans, “he mused that Americans are benevolently ignorant of Canada, while Canadians are malevolently knowledgeable about the United States.” The sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset, on the other hand, described the U.S. and Canada as two trains, traveling on parallel tracks, that would neither collide nor meet. Still, Canada is clearly in some sense obsessed with America and the places where the two countries’ similarities end and their differences begin. Canadians feel a palpable alienation from their neighbors, with shades of both inferiority and superiority. As Jennifer MacLennan argues in her essay “Dancing with Our Neighbours: English Canadians and the Discourse of Anti-Americanism,” this dynamic is best understood by seeing Canada as a kind of cultural island, whose “relationship to its cultural ‘mainland’ is inevitably one of conflict and paradox.”

This island concept is a useful way “to maintain a strong and necessary sense of ‘us’ amid the prevailing influence of ‘them.’” Put simply, Canadians feel marginalized by American cultural bombardment, yet consistently seek out its products, producing an emotional and political paradox. As one of Canada’s most celebrated prime ministers, Pierre Trudeau, famously said at the Washington Press Club in 1969: “Living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast, if I can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt.” As Not-Americans, Canadians proudly distinguish themselves in politics, social life and temperament, but always sleep with one eye open, facing southward.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.