Fennel bulbs and date branches are stacked up on the market stalls and vendors invite people to come closer. The old man walks toward the open market square. Several excited children already wait for him there — they’ve been waiting all week. Others will join later, once he begins.

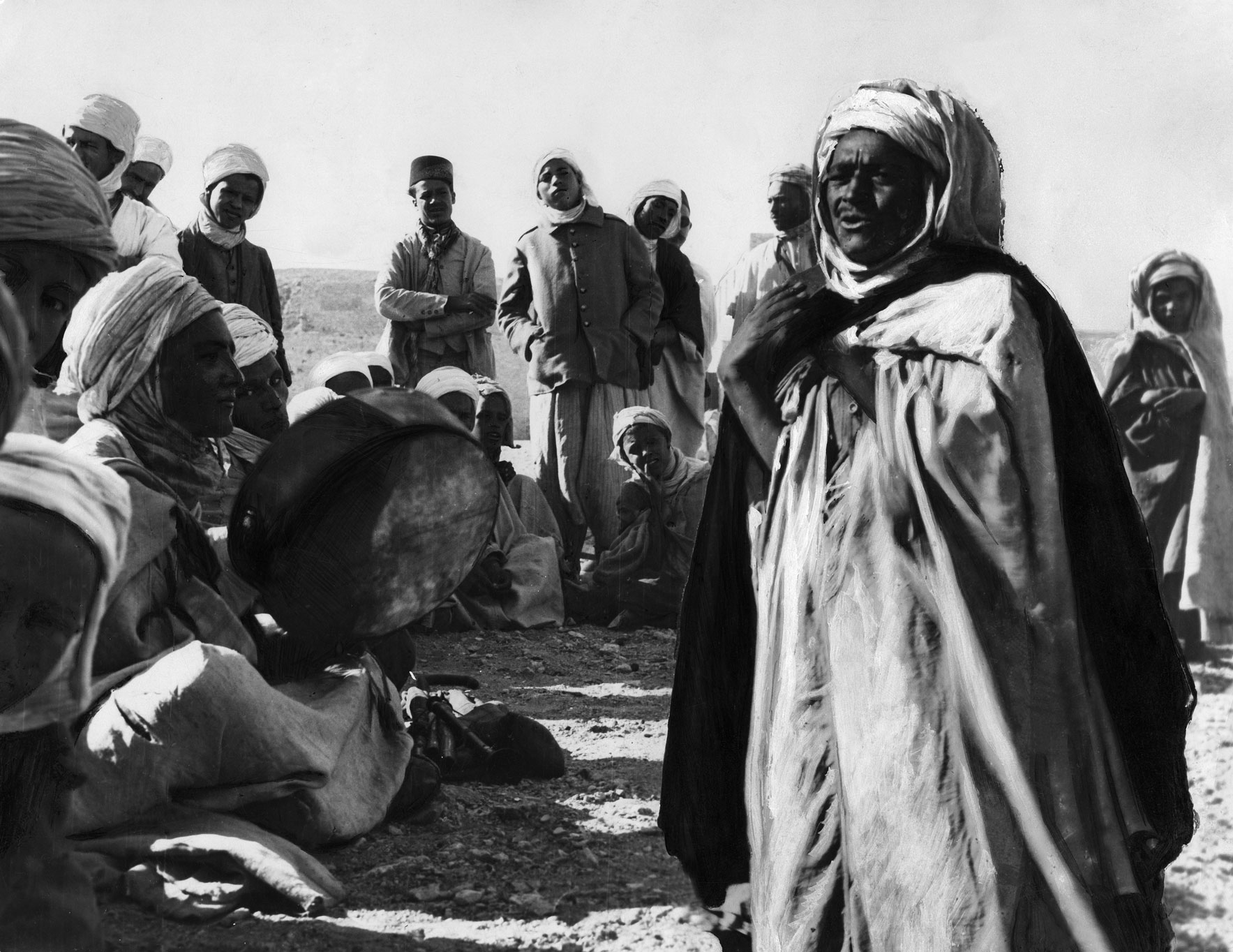

First, the man lays out pictures on the floor. Some are print reproductions; others, he drew himself and reuses for every performance. He mechanically dusts them off, straightening the folds. He has practiced this ritual for decades, and refuses to rush these steps. They help him get into character. A young boy in the audience — my father — recognizes in one of those pictures the figure of Ali, the prophet’s cousin and son-in-law who ruled over lands stretching from Egypt to parts of Afghanistan during the seventh century. Dressed in a shiny soldier’s uniform, astride a black horse, Ali swings Zulfikar, his double-pointed sword. My father told me how he and the other children would fight to get seats closer to the pictures. They sit. The bard, wearing his long, hooded robe, a brown qashabiya made from wool, is about to begin his story.

Fdaouis are the traditional bards or storytellers of Tunisia. They’ve been around for as long as people can remember, retelling a myriad of old stories and keeping folk culture alive, just like Scheherazade’s “1,001 Nights.” But in the years since my father eagerly listened to stories in the marketplace as a child, shifts in technology, media and the economy have pushed the bards to the margins, and they have nearly disappeared. Yet while the ritual of sitting down in a public square listening to stories only survives in people’s memories, a new generation of storytellers are reviving the art form and taking it in new directions.

Stories about Ali and his heroic feats of military might were always popular. He shone at the Battle of Badr in the second year of the Islamic calendar (624 CE), where he defeated a strong warrior from Mecca in a duel. Ali counted on Zulfikar, a sword said to have been acquired from the hands of the prophet — a mark of high esteem. The story sometimes changed and Zulfikar came to Ali as a miracle: God transformed a tree branch into a mighty sword. A sword, falling from the sky! With Zulfikar, he was invincible in the critical early days of the Islamic conquest. Angels even came to his rescue. He resisted the tricks of his enemies, which included women singing and reciting poetry, seeking to weaken the resolve of good Muslims like Ali.

But the story my father listened to as a child that day in the market was about the combat between Ali and a monster called Ras el Ghoul, the boogeyman of pre-Islamic Arabia. My father recalled how the bard reenacted this fierce clash as he hunched his back, modulated his voice to signal an upcoming danger, deftly swung an invisible sword and dodged several imaginary blows. And it worked. My father and the other children felt Ali’s strength and determination. “No man is like Ali and no sword is like Zulfikar!” the bard proclaimed and the audience repeated. The children screamed in concert when the ghoul was approaching. They cheered loudly when the monster was eventually defeated. Around them, the white noise of the marketplace continued but theirs was another world, a world of righteous combats and quests.

Ali is, perhaps, a curious character to enjoy such popularity in Tunisia, since he’s most commonly associated with Shia Muslim communities. But his presence is a reminder that Tunisia was once incorporated into the Shia Fatimid Caliphate, which ruled over large swaths of North Africa between the 10th and 12th centuries. Stories about Ali are just one part of the idiosyncratic mix of Tunisian tales, which also includes popular local stories highlighting the country’s regional diversity, stories from the Ottoman era and stories from the broader Islamic world akin to the “1,001 Nights.” Tunisian Jews and Amazigh people have also kept their own storytelling heritage alive.

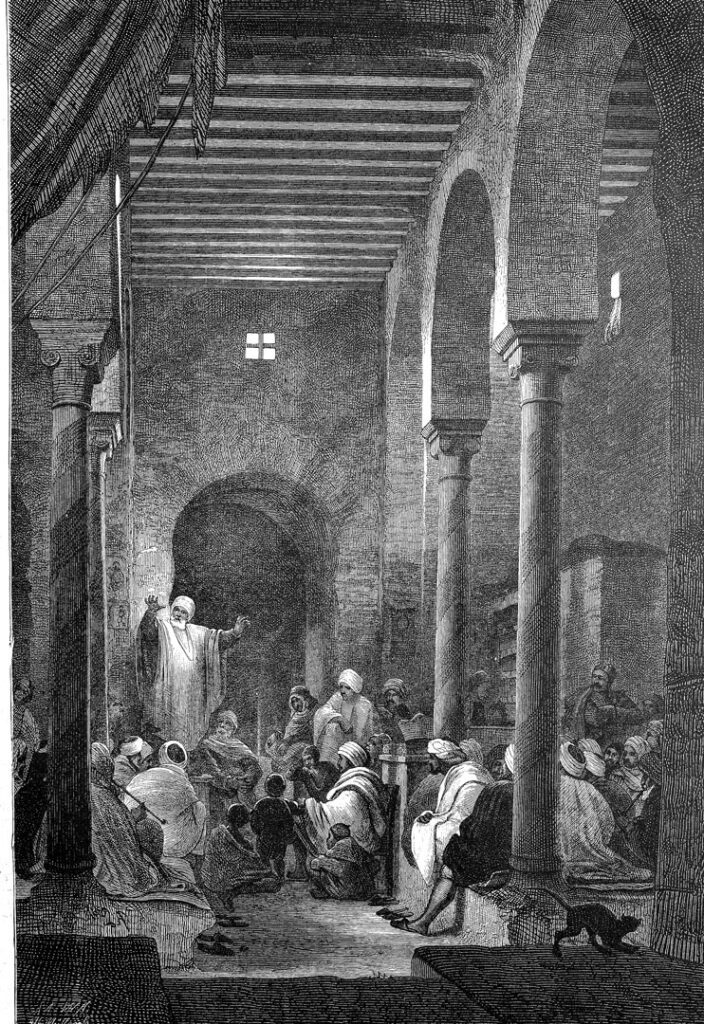

Fdaouis largely worked in public spaces — cafes, markets, squares, hammams. Some cafes even had their own bards. Amid the smoke, chatter, arguments and laughter, they entertained, distracted and made their living. Professional bards mostly performed to an audience of men, since cafes were men-only spaces and hammams sex-segregated. While it was frowned upon for a woman to linger outside her home and listen to the stories of a man who might be trying to seduce or corrupt her, many women did participate in this folk art, sharing their stories at home. Within a family or social circle, women would designate whom among the mothers, aunts, grandmothers and sisters were most skilled at storytelling. That’s how my aunt became our family’s unofficial fdaouia — mostly because once she gets started, no one can stop her.

Following my father’s recollections, I was drawn to explore the world of Tunisian bards. Their vast repertoire of stories varied, but a few popular archetypes shone through. There were stories about the aroussa, or bride, the azouza, or old woman, rich businessmen, sultans and poor, unfortunate souls. Matrimonial conflicts and inheritance disputes featured heavily. Stories could last for days or a few minutes. On the shorter side, Tunisian bards drew on the Joha repertoire, a popular folk character encountered in stories from Central Asia to North Africa. Joha, also known as Nasreddin Hodja in Turkey, is an irreverent trickster, who often finds himself in grotesque situations. One day, Joha goes to the marketplace. He stops at a grilled meat stand; it looks tasty. Suddenly, the merchant asks him to pay. “But why?” asks Joha, who didn’t eat anything. “You smelled my meat, so you must pay!” Joha takes out a coin and puts it inside a tin box. He shakes the box several times and faces the merchant. “Now pay me, since you listened to the clinging of my coin.”

Epics took days to narrate. Among them, the Arabian epic of Antar, a knight and poet, who may have influenced Arthurian romances. He fights to marry his beloved Abla, which leads him on countless adventures to demonstrate his bravery. But the most famous of all epics was the “Sirat Bani Hilal” or “Al-Hilaliyyah.”

At nearly 1 million verses, the epic is one of the longest historical poems that bards memorized from one generation to another, and, as it was often told at weddings and other family celebrations, its story is woven into the fabric of Tunisian society.

As steaming piles of couscous were served, families in their finery would gather around the bard to hear the story of the harrowing journey of the Banu Hilal Bedouin tribe and their leader Abu Zayd to Tunisia. Bards, often accompanied by a troupe of instrumentalists, would recount the familiar story of Abu Zayd’s ominous birth — a black bird appeared to his mother when she was pregnant — and the hardships he endured to become a worthy hero.

But the true heart of the story lies in the journey into exile of Abu Zayd and the Banu Hilal confederation of tribes he leads. It’s an Arab “Iliad”-meets-“Holy Grail.” Years of scarce food and low rain precipitate the departure of the tribe from their homeland. This migration, called the “taghriba,” did historically occur during the 11th century. Tens of thousands of Arabs marched westward to southern Tunisia, and, in the epic, they encounter many more detours and adventures after a first reconnaissance mission runs into complications (involving a seductress, a snake and other temptations and hazards). The segment of the story that describes the tribes’ Tunisian peregrinations could take a full day for bards to recount. It’s a tragic story of conquest and collapse. United during war-time, Abu Zayd and his tribesmen inevitably killed each other for the spoils.

People would listen to this world of a nomadic lifestyle, chivalrous qualities and the blood-tinged nature of conquest amid their celebrations and major life moments. They saw themselves as the sons and daughters of these fictional heroes populating stories that include true historical elements. While the epic was included in UNESCO’s list of works of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2008, its oral performance, much like the fdaouis themselves, has mostly vanished.

Despite persisting in communities for centuries, traditional storytelling began to shift in the 1960s, and with it the places where bards performed. “Places of conviviality have changed,” observes Ahmed Hafiz, a self-described “all-terrain” Tunisian bard based in Belgium. The screenwriter-actor-singer has been reviving the art form for the last two decades through new stories and solo shows. With the advent of the gramophone, radio and television, the figure of the fdaoui has had to adapt to new preferences and audiences. Tastes changed. In cafes, people began listening to music, and even more of them watched football games.

Hafiz owes much of his vocation to Abdelaziz El Aroui, a journalist turned storyteller who rose to prominence as a new kind of fdaoui at the time of independence through popular radio and TV shows, notably the series “H’kayet El Aroui,” (“El Aroui’s Stories”). During Ramadan, families gathered to await these stories. Children and adults tuned in to Radio Tunis frequencies on Sundays, not to miss another one of his tales, such as “The Woman And The Lion.”

One can almost picture a child turning up the volume of the radio in the living room, his hands moving away from the device once he hears El Aroui’s first words. He sits, listening wide-eyed to the story of a woman married to a lion who goes to visit her mother for the first time since her wedding. In the story, the mother asks her daughter if she’s being treated well, if she’s happy. The daughter says yes but immediately criticizes her husband’s bad breath. She doesn’t know that her lion husband overhears the entire exchange. At home, the lion asks his wife to hit him hard with a sword. She stares at him, puzzled, and obeys. The wounded lion then confronts her. He heard everything, he says. She’s livid. “Bad mouthing causes deeper scars than the ones you physically inflicted on me with the sword,” the lion adds. He then eats her. The listening child — no longer hungry — learns a lesson of tolerance, to refrain from speaking ill of others.

Most Tunisians associate storytelling only with El Aroui, who passed away in 1971. Affectionately called “Baba Aroui,” his stories have been compiled and published in book form. Today, a YouTube channel has compiled over 11 hours of El Aroui’s tales; there’s even an app to download his stories. (When I told this to my father, he immediately asked for its name — “Abdelaziz El Aroui” on iTunes.)

El Aroui retold popular stories in his unique style — a succession of vibrations and pauses he could command at will. He also cut an alluring figure as his outfit departed from the traditional long robes of bards; instead he wore a suit and a tall felt hat that invoked Ottoman times. His singularity made it difficult for others to follow in his footsteps, since he became a point of reference. “There is a technique not to lose people in details, to bring people along through speech, diction, pace, pronunciation,” says Hafiz, who creates original fdaoui shows which include light-touch music and darbouka drums. He is part of a generation of Tunisian artists who are shaping a post-El Aroui tradition.

While TV overtook traditional fdaoui in cafes, theater has attempted to revive the art form since the 1980s, through modern one-person shows and stand-up comedy. Storytelling has modernized, even if it only requires a teller and an audience: Whereas before, people could spontaneously join a performance once it had begun and tip the bard, now tickets must be bought. A production team arranges the setup. Tunisians continue to cherish the storytelling of their bards as a living, transforming heritage. And as the Tunisian arts scene has preserved this heritage, even nonprofessionals have joined in.

In his 50s, Hamouda Alias tells me by phone that improvising tales helped him fit in at school when he was younger. As he told stories, he made friends. The idea of creating his own YouTube channel emerged during Ramadan of 2015, when he and his family found all the Ramadan TV shows lackluster. Eight years later, his series “Forgotten Tunisian Stories” boasts over 170,000 subscribers and nearly 300 videos.

Alias educates me. When the tales feature camels, they come from the south, and from the north when we encounter horses or horse-pulled carriages. Though his videos include sounds and images, he keeps them to a minimum so as not to interfere with the “charm” of listening to a story. Often, he recalls stories from his own memory and subscribers sometimes share new ones with him — his passion has turned into a participatory project. One of his longest videos, about a family who learns to survive after the death of the father, and the sacrifices they make, drew close to 1 million viewers in November 2020.

Alias considers the fdaoui world a space protected from the increased political polarization of post-Revolution Tunisia. He notes that his channel has seen “no bad words or insults in eight years,” even though the country’s divisive politics regularly overflow on social media. Women, men and families follow his videos, which speak to everyone’s “inner child.” It’s the world of our great-great-great-grandparents. “We’re all children,” he tells me.

Though he claims not to be a professional fdaoui, Alias tells me stories of bride kidnappings — a mysterious hammam disappearance attributed to a djinn, or the time the earth cracked open and the bride fell in the abyss on her way to her husband’s home (a past lover swept her away and this was their escape). Like my aunt, he’s unstoppable. We’ve been speaking for almost two hours and he suddenly mulls over the ghoul. “There’s no historical text on cannibalism in Northern Africa,” he says. He then explains how the descriptions of North African ghouls differ from their Middle Eastern counterparts. The Tunisian ghouls are “more human” in their appearance; they often take the form of a woman, not so different from a Medusa with wild, unkempt hair. Alias doesn’t say it directly but leads me to consider whether the Tunisian ghoul — my father’s childhood nightmare, which he laughs about as an exorcized terror — symbolizes the taboo of cannibalism in our society. I wonder whether he’s telling me more stories now or reliable information. This is the magic of fdaouis — they suggest, plant ideas and leave you with your own ruminations.

Like most professional and amateur fdaouis, Alias loves the past but is also mindful of the present. I ask him about women and minorities. Apart from Al Jazia, the fearless female companion of Abu Zayd, the main character of the “Sirat Bani Hilal,” I couldn’t name other women who weren’t helpless brides, cunning wives or wicked aunts and in-laws. Were there any? And what about common Black or darker-skinned people who weren’t Abu Zayd or Antar, often reduced to roles of slaves, eunuchs and scapegoats, perpetuating harmful stereotypes? “Some of these stories are racist. I had to change them,” Alias says. Fdaouis are observant — witnesses. They hold a mirror up to us. I ask the same thing of Hafiz, who writes his own shows. Stories “reflect a period and a society,” he tells me.

The question of old versus new reemerges in a conversation with Hatem Bourial, a journalist and prominent contemporary fdaoui artist. “What interests me is how to be a fdaoui today,” he says. He recently collected stories from Bhar Lazreg, an area north of Tunis where many Black asylum-seekers and migrants live. His newest show features a Black African storyteller, a choice that invites the audience to consider storytelling as a grafting process through which different traditions can coalesce to create even better stories.

“How did the trans-Saharan trade influence stories and characters?” asks Bourial, as we speak over WhatsApp voice messages. We often hear that Moriscos brought their tales when they fled from Andalusia to Tunisia in the 17th century. But we don’t know much about the cultural cross-pollination that might have happened — whether a Morisco may have first heard a tale from a North African bard. Tales, like humans, are a feat of mobility and cultural exchange, sometimes forged in violence.

Today, the coastal city of Sousse and the desert oasis of Douz continue to celebrate the figure of the fdaoui. Sousse has organized “fdaoui days” in its ancient ribat, in public squares and at the nearby archaeological site of Takrouna for the last two decades. Workshops organized at the margins of the festivals attract dozens of aspiring fdaouis — men and women, children and young adults. The Tunis-based contemporary “art station” B7L9 organized fdaoui performances in 2019 to reinvigorate cafes and other public places.

“Fdaouis are part of a collective memory, and even perhaps a collective unconsciousness,” says Bourial. The traditional fdaouis formed a repository — a genealogical memory, with themes and characters that contributed to the spirit of a national identity. Engaging with the present and upcoming bards may take us to new, more inclusive lands of imagination. The moral of this story is that we need them.