After the end of World War I, with the guns now silent, people from the Levant journeyed to Europe and lobbied to settle their fates. Exhausted by their own famine, feuds and repression of late Ottoman rulers, people around Lebanon greeted the end of the war with joy and relief — only to then grow weary and anxious. Melkite Catholics were among these people, part of a generation who helped establish and shape contemporary Lebanon.

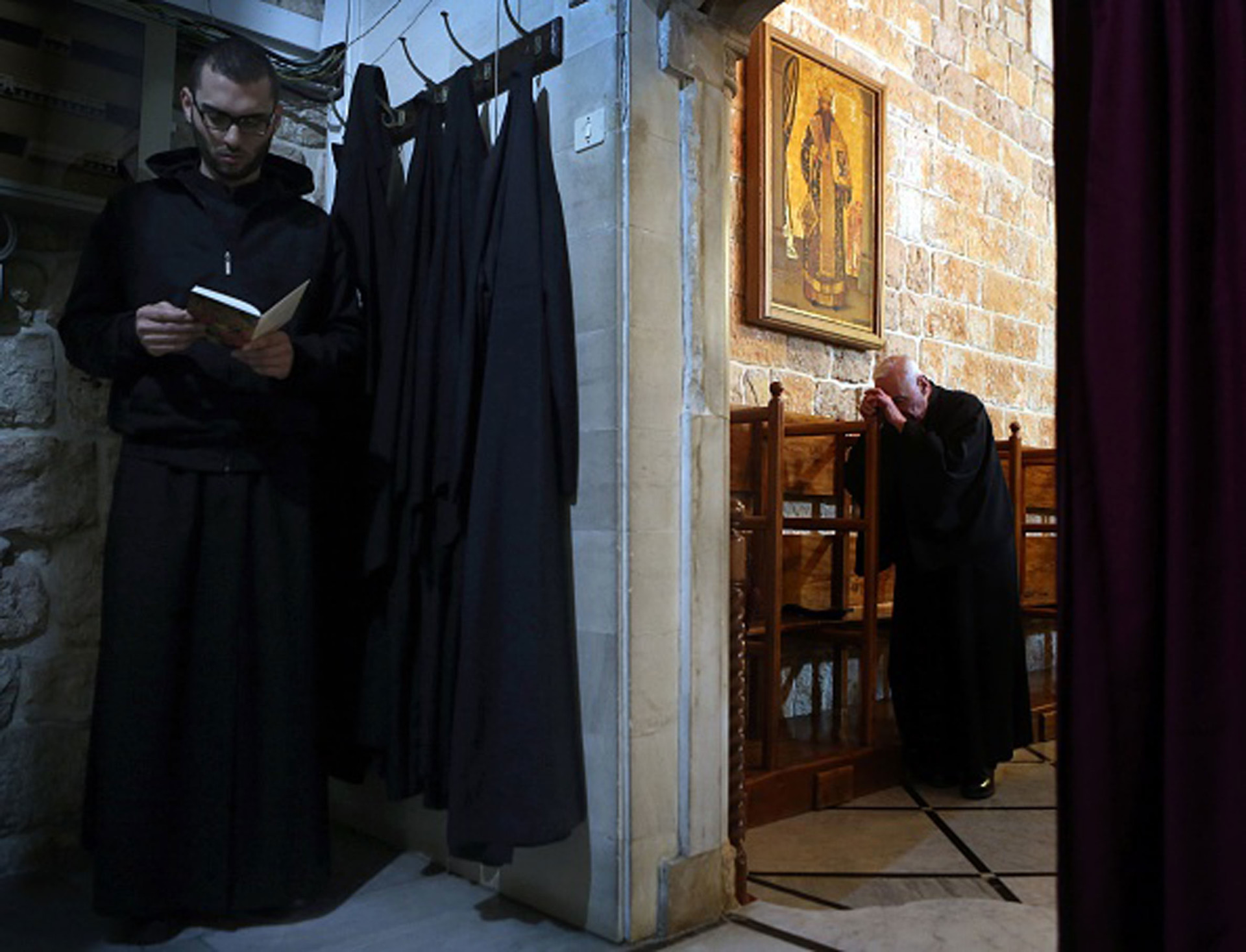

As the French considered different ideas, with some still ambivalent about the idea of a Greater Lebanon, Cyril Moghabghab decided to join the second Lebanese delegation heading to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. While members of the delegation were mostly Maronites, Moghabghab was the Melkite Catholic bishop of Zahle (a town, on the edge of an autonomous area in the Ottoman Empire, whose residents had interests in the mountains and plains). The Melkite Catholics, more broadly, straddled two worlds. While they were Christians who retained liturgies and rituals rooted in eastern Christianity, including Orthodox beliefs and the Byzantine Rite, they descended from folks who entered full communion with Rome in the 1700s. They lived throughout the Levant, including of course in and around the Bekaa Valley. In addition to being the only Melkite (along with his secretary) in the delegation, Moghabghab was one of the key voices among Christians living in those plains — long home to others, like Shiite Muslims, with their own influence and perspectives.

Maronite Patriarch Elias Howayek, a founder of Lebanon, led the delegation. Boarding a French warship in Jounieh, then a little town with a harbor north of Beirut, the delegation’s members cruised to France and made their way up to Paris. Echoing a resolution adopted by the administrative council, the delegation members called for the “political independence of Lebanon in its geographical and historical frontiers.” The French had been unwilling to discuss the frontiers of a prospective entity, fearing it would sabotage their attempts to reach a compromise with Faisal I, who was establishing a quasi-independent Arab government in the Syrian hinterlands.

In the previous century, Mount Lebanon had acquired autonomy under different frameworks. But the status of the plains between Mount Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon range was unclear and contested by the early 20th century. On the one hand, Arab leaders sought to include it in a larger state. When the British prevented the French from asserting their control over the Bekaa Valley, Faisal visited the area, proclaiming that Lebanon, “the pearl of Syria,” would be a part of Syria. On the other hand, leaders from Lebanon wanted to include the plains in their prospective state. According to stories since circulated in the Beirut press, Moghabghab then told French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau that “Lebanon is a refuge for the persecuted seeking freedom, so how could it be content with the rule of the Sharif of the Hijaz, who embodies both a religious and civil authority.”

Maronites in the delegation understood the importance of the Bekaa. They were still struggling with the consequences of a famine in Mount Lebanon, where Ottoman rulers, European policymakers and area elites aggravated nature’s wrath with their brutal repression, poor policies and collusion. The Bekaa was Mount Lebanon’s most important grain supply, with even Emir Bashir Shihab II deeming its rich plains a necessity for survival. (Maronites had other reasons, from spiritual and political connections to scattered communities and land, for wanting to include the Bekaa Valley within the realm of Lebanon.) While Maronites and others saw the Bekaa as a breadbasket, Moghabghab and other Melkites looked past recent horrors and beyond teleological — but still relevant — ideas of political evolution. As Melkites, they had to grapple with the reality that most of their coreligionists were scattered all over the Levant and Egypt. Even Melkites in Lebanon’s cities and towns were still connected — through faith, marriage and business — to people throughout the Levant.

Melkites had complex views and interests of their own. Established in the 1700s, their now-Catholic church was not — and did not operate or see itself as — a national one. Emerging from Orthodox Christianity, the Melkites were not as aligned with Ottoman authorities as their clerical counterparts had sometimes been. They felt Lebanon’s pull and, especially at the time, retained ties throughout the Levant. At least for Moghabghab, a bigger Lebanon helped with the dilemma. Some elites, landowners and traders — some living in towns like Zahle, others running enterprises everywhere from Aleppo and Alexandria to Palestine — also agreed.

Moghabghab also had to think about migration. Beginning in the 18th century, Melkites of Aleppo, Damascus and the Syrian interior migrated to Lebanon — joining counterparts who, like other Levantine communities, were already dispersed there. Orthodox Christian clergymen complained to the Sublime Porte, frustrated about their loss of parishioners — and properties — to those who were converting to Catholicism, or at least acknowledging the primacy of Rome. The Ottomans responded in a heavy-handed manner, generally — but not always — favoring Orthodox clergy over Catholic counterparts while protecting their turf from different kinds of European encroachment. Clamping down, they arrested, moved or deported members of the community.

They went to Lebanon. Even if the idea of Lebanon as a historical refuge has been exaggerated, many Melkites of the time looked at the area that way. Melkite attraction to Lebanon was neither natural nor inevitable, but they nonetheless moved, settled and were welcomed there with little controversy. Despite tensions and disagreements, Maronites and Melkites got along well enough in Mount Lebanon because of their shared Catholicism, assertive elites and different connections with the world outside the empire. In the wider area of Lebanon, moreover, Melkite Catholics maintained complex relations with Shiite and Druze elites — both of whom generally protected or remained indifferent toward people practicing their still-nascent faith. In the Bekaa Valley, Shiite families initially welcomed Melkites, who brought wealth to their area of influence. Building their first church in Zahle, already Christian by then but still Orthodox, Melkite Catholics also established a presence in a town that would later become their seat of influence (and the so-called “Catholic capital” of the East).

By the early 20th century, elites and residents of the once-autonomous town had wedded themselves to this idea of Lebanon — at least according to Moghabghab. The story may be apocryphal, but he is said to have told British Prime Minister Lloyd George that “Zahle would rather starve to death than be separated from Greater Lebanon.” His declarations fell on friendly ears. Listening to Moghabghab, who made the case for including more of the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon, Clemenceau, the old lion of France, promised simply to make this “legitimate request” happen.

Moghabghab may not have carried the day alone. He was one among many who made similar claims. Aside from Zahle elites, landowners, traders and clerics with land and other interests in the Bekaa Valley made the case to expand Lebanon. Moreover, the French and others did not consult as closely with Levantines — even these Lebanese, or aspiring Lebanese — in their final deliberations over whether to create Greater Lebanon. Without a doubt, though, Moghabghab helped broaden the base, emphasize eastern lands and consolidate a sort of Catholic convergence around an idea of Lebanon — the Lebanon we know today.

Converting to Catholicism and building a new church, different Melkites worked with missionaries over the years. They were exposed to European, often French, education and culture. Already trading in the Levant, Melkite Catholics were increasingly accessing European markets through these connections. They began to prosper in trades, banking, commerce and textiles. A new Melkite mercantile bourgeoisie emerged in Aleppo and the port cities in Lebanon and Egypt. By the late 18th century, these merchants had created or involved themselves in trading networks stretching from India to Italy — eventually contributing to a decline of French trading houses in the Mediterranean. (When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, at least some bitter French merchants sighed in relief. The emperor saved them from bankruptcy.)

The Pharaon family, whose members were among Lebanon’s founders, also emerged in this environment. A family with origins in the Hauran plains as well as different Levantine cities and towns, they began making their fortune in Alexandria. Henri Pharaon, perhaps the richest man in Lebanon during his time, had moved to Beirut from Alexandria with his family when he was a child.

A politician, a passionate art collector and effectively the owner of Beirut’s port, Pharaon would go on to play an influential role in shaping modern Lebanon. Along with relatives and friends, he would help broker the different deals upon which Lebanon’s political system was built. Pharaon’s home in Beirut was a rendezvous for Lebanese leaders of all stripes — and often a neutral ground, untouched during the Lebanese civil war, for opposing leaders to have discussions. He embellished its interior with vast collections of early Christian antiquities and Islamic art. Years later, Pharaon shared this sentiment: “I wanted to make this house, my first homeland, what we wanted to make of Lebanon.”

Two decades after Moghabghab witnessed the birth of Greater Lebanon, the bonds holding it together had proved to be shaky. As they had in preceding decades, Muslim and Christian gangs fought in the streets of Beirut and surrounding areas. Beirutis with older roots in town protected their turf, while feuding among themselves. Migrants from the mountain and their descendants edged in on the action as well. People also battled over ideas, experiences and visions: the Maronites asserting that of Lebanon, the Sunnis answering with those of wider Syrian or Arab entities. Others lined up with their own ideas, perhaps of a predominantly Christian political community in which non-Maronites would have a greater role, or perhaps larger entities with autonomous areas allowing communities — or at least their elites — to run things as they saw fit.

Now in another of their homes, Beirut, Melkite elites had a lot to gain from easing social tensions and modifying these ideas. Some of them understood their own interests quite well. Pharaon was one such person, a financial titan who benefited from Lebanon as a haven while also looking after significant interests across the Levant — and beyond. Michel Chiha, Pharaon’s brother-in-law, was another such person.

A banker and writer, Chiha was a Christian who belonged to two communities. While Chiha’s father was a Chaldean Catholic, his mother was a Melkite from the Pharaon family — again demonstrating the incestuous nature of elites, however bright or seemingly transcendent, in Lebanon. He co-owned Banque Pharaon & Chiha in Beirut, working with Henri Pharaon. He also wrote about Lebanon, as a place and as an idea. While they were not as influential in the foundation of Lebanon as suggested retrospectively, Chiha’s political writings would serve as a theoretical basis for different Lebanese attempts to resolve social and political tensions in their new, pluralistic entity. Pragmatic in some ways, Chiha knew that if Lebanon was going to work, Sunni Muslim grievances and Christian concerns both had to be toned down. He also asserted that others — Shiite Muslims, Druze and so on — had their own designs, concerns and fears.

While Chiha saw Lebanon as a refuge for various communities, he expanded the idea with allusions to a marriage between “the mountain and city.” Like others, he saw Lebanon as a “place of refuge and a meeting place.” This marriage, however, meant that each of Lebanon’s minorities needed to be represented, even if it came at the expense of the individual citizen. Although Chiha often dismissed the concerns and fears of the various communities as exaggerated, he believed some sort of guaranteed representation would ensure no one felt left out. Indeed, no other country in the region would go on to give so many different communities, including small minorities, a voice, but the consecration of confessionalism also had a price, and it was an expensive one.

After Moghabghab and other Melkite Catholic elites and clerics helped Maronite counterparts work to create Greater Lebanon, Pharaon and Chiha helped successor elites in different communities reconcile all the ideas that went into making the polity a republic. Pharaon and Chiha were business-oriented men who situated themselves between people negotiating the new Lebanon, even as at least one of them — Chiha — wrote that the negotiation itself was at the heart of that Lebanon.

Notwithstanding their individual contributions to the formation of Greater Lebanon, Pharaon and Chiha were also products of their environment. The familial and communal experiences that shaped them unfolded against the backdrop of decadeslong changes in Christians’ interactions with others in the Levant and beyond. For instance, these men’s ancestors had migrated after being expelled from or squeezed in Aleppo. Others fled to Beirut from Damascus, where mobs massacred Christians after the 1860 clashes in Mount Lebanon. They all remembered, because their families spoke of their status as second-class citizens in the Ottoman Empire. Unlike the Maronites, who had a complex but different experience in the empire, many Melkite families had more recently lived under legal and other political inequality in a wider Islamic-ruled region. And even if they had not always lived that way or were perhaps glossing over some of the advantages they had acquired, Melkite Catholics among Lebanon’s founding fathers believed this to be true. With that in mind, they were finally exercising a degree of agency in shaping the future they wanted.

Joining established elites of Beirut, where Sunni Muslims and Orthodox Christian elites had long held sway, Melkite elites were not as assertive as the Maronites who had also migrated in larger numbers to the city in the preceding century. But they were influential, throwing their commercial weight and connections behind their political aspirations.

After Melkites helped establish the republic, Lebanon’s pull on their coreligionists in the region would, once again, be felt alongside pushes in other states — including Syria and Egypt. As the French were leaving Syria in the 1940s, many pan-Syrian nationalist and pro-independence groups treated Melkites with suspicion due to their alleged pro-French sympathies. Partisans of these groups often thought of Melkites as “outsiders” in their political community. After Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power, he in 1958 established the United Arab Republic (UAR): a political union between Egypt and Syria. With authoritarianism and other restrictions, thousands of Melkites left Aleppo and Damascus to settle in Lebanon. They mainly settled in Beirut’s residential neighborhoods, including Badaro. As these two countries dealt with brain drain and capital flight, the newly arrived Melkites invested in the local Beiruti economy and opened businesses. “Like many families from Syria and Egypt, my father came to a promising country, with a truly free press” and a “reassuring Christian presence,” remembered one of these migrant’s sons. He is now a filmmaker — and Lebanese.

Even with their attendant privileges, the men had difficult final chapters in their lives. The breakdown of the state, pact, institutions and relationships demonstrated how out of touch some of these men had been — or had become — despite their political pragmatism. It was, after all, a pact made by elites for elites. Moreover, each of them suffered some unfortunate personal circumstance.

Later elected the Patriarch of the Melkite Catholic Church, Moghabghab exhausted himself battling against the French government and European missionaries who maintained colonial mindsets and policies towards his church. He clashed with others, until Pope Pius XI demanded that Moghabghab resign. Refusing, Moghabghab lived much of his life at odds with those in his own house.

Pharaon and Chiha kept struggling with diversity and politics in Lebanon. In hindsight, Chiha’s worries about minority representation were not ill-placed. Others in Iraq and Syria, who believed that secular nationalism could cover up sectarianism or pluralism, did not fare much better over the decades. However, spending his final years focused on the Palestine question, Chiha also cast many doubts on whether the pact he engineered would be able to withstand a turbulent event like the creation of Israel. Troubled, he died before he could see some of his worst fears come true.

In his long life, Pharaon became a tennis champion, married a Maltese heiress from Jaffa and served twice as minister of foreign affairs. As Lebanon struggled and stagnated, Pharaon frowned at the way different Lebanese had implemented the bargains he once helped broker: “The [National] Pact has been interpreted too rigidly. The confessional distribution of offices of state, let alone of civil service posts, was not intended to last forever. It was thought of as provisional. It was not an essential element of the Pact.” Living until after the Lebanese civil war, Pharaon suffered a violent death that was as ghastly as the Lebanon that had been ripped apart. He was stabbed multiple times in his bedroom in Beirut’s Carlton Hotel. The killer was never caught.

None of these or other Melkites, except perhaps Chiha, have had their share of recognition in the conversation about Lebanon. They might have seemed invisible. However, they were not irrelevant. They were involved in Lebanon’s creation, for better and for worse.