In February 2016, I was neck-deep in research for my first book, “The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age.” As I often did in those days, I took some time away and went into what I called Malcolm’s World. King and Malcolm X had been dominating my free time ever since 2012. So when I stumbled upon Garrett Felber’s guest post about Malcolm for Black Perspectives, a blog run by the African American Intellectual History Society, I grabbed some coffee. Felber, like me, knows how to dig, and what he found changed my career: a previously unknown poem penned by Malcolm himself.

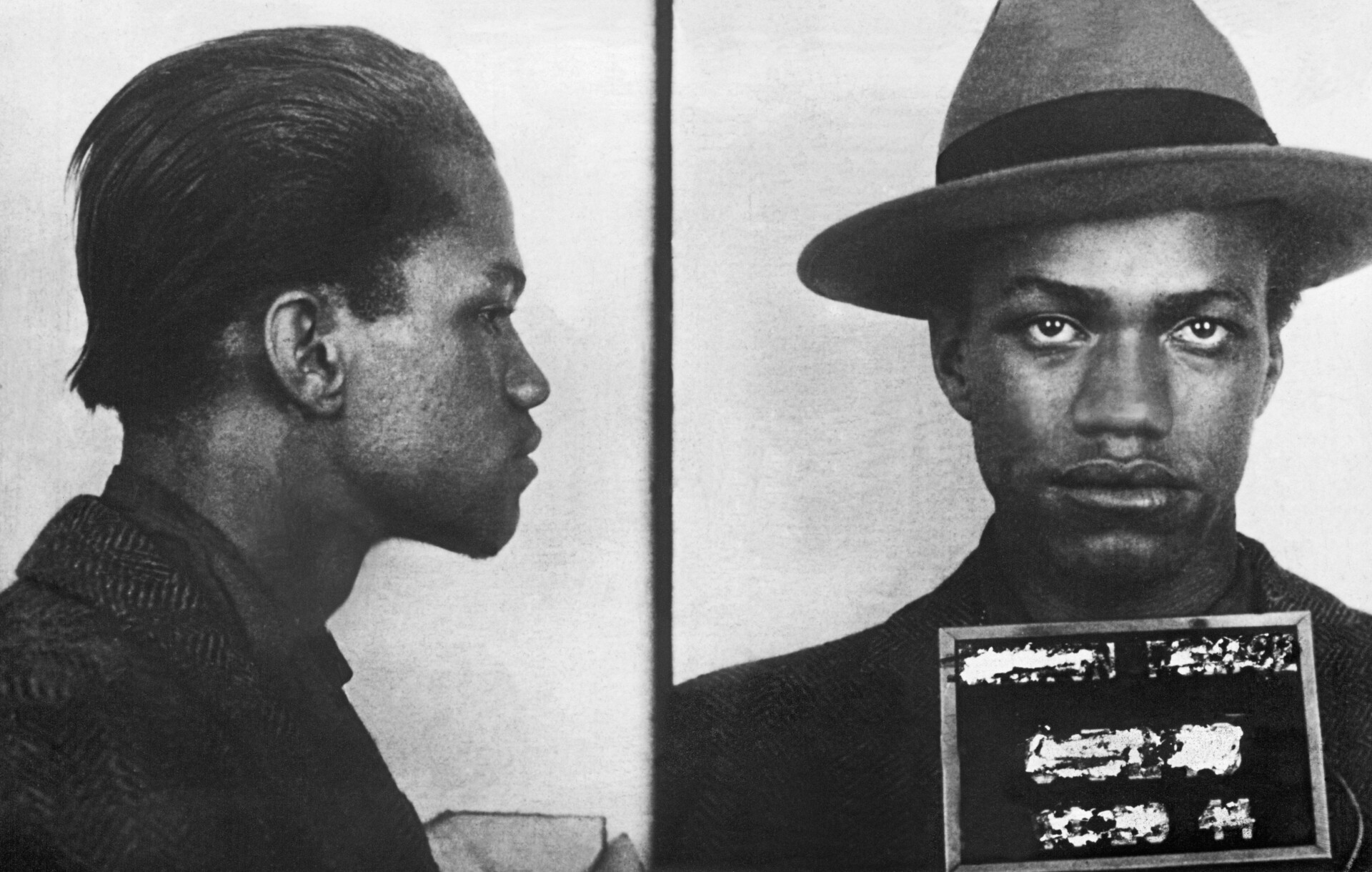

Malcolm had a difficult childhood. In 1931, when he was 5, he lost his father in a horrific trolley accident. In late 1938, his mother — who, for years, had managed to keep Malcolm and his six siblings together — was admitted to a mental hospital. Malcolm moved to Roxbury, Massachusetts, soon after to live with his half-sister Ella, and his life markedly changed. He met jazz musicians such as his lifelong friend Malcolm Jarvis, to whom he would send the poem, and started selling drugs and stealing. Jarvis had been a part of Malcolm’s burglary team, and they were both sent to Charlestown State Prison in February 1946. Three months later, Jarvis was transferred to Norfolk Prison Colony, where Malcolm would eventually join him in March 1948.

At Norfolk, he wrote the poem, which would be preserved only through a historical accident and discovered in an archive many decades later. He wrote it in July 1949, when he was 24, and sent it to a friend whose correspondence was kept for posterity by Jarvis’ psychiatrist. When I first read it, my eyes began to water. I’d already been researching Malcolm’s life for several years, and the poem felt like a large window had opened, letting in new air. Here he was, young and struggling, searching for his voice behind prison walls.

When you listen to Malcolm speak, there is a poetic rhythm in his delivery, as if he knows precisely which word to deploy, and at what speed. These communicative abilities were partly forged through music and partly through the reading he did while at Norfolk. The poem shows him at this stage, experimenting with language. In yet another historical accident, this level of reading could only have been done in a progressive institution like Norfolk, with its huge library and commitment to rehabilitation. Malcolm was to explore his burgeoning faith in Islam, pursue intellectual issues to do with race and society and discover vast amounts of poetry — all of which would combine to form the leader he became.

“Red” was Malcolm’s nickname as a teenager due to his reddish hair. “Little” was his family name, though he would later consider it his “slave” name. “I never acknowledge it whatsoever,” he said in a 1963 television appearance.

But he was still acknowledging it in 1949, when he affixed it to his poem. When I saw the name, I realized the poem had been written when Malcolm was at a spiritual and intellectual crossroads. As I would find out years later, the poem was written around 10 months after he had first decided to join the Nation of Islam. In July 1949, Malcolm was still exploring how he felt about his faith.

The two other names on the letter are Malcolm L. Jarvis and Abdul Hameed, both added by a prison official to give the psychiatrist the context for the letter. While at Norfolk, Jarvis was Malcolm’s best friend, but the two men had a complicated relationship. When Malcolm first moved to the Boston area in 1941, at the age of 15, he met Jarvis, two years older, at a pool hall. They quickly became friends, their shared love being jazz music. Jarvis played the trumpet, and Malcolm often danced and emceed as “Rhythm Red” at various bars and clubs. At some point around then, Jarvis introduced Malcolm to Hameed, also a musician with Lionel Hampton’s band.

I knew the context of the friendships reflected in the letter, but I had so many questions, most of them revolving around the culture of the prison he was in. How had Malcolm been able to write such a rich poem? What was he thinking as he wrote it? What were his influences?

Ever since discovering “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” in my early 20s, I had wanted to learn as much about his time in prison as I could. In the autobiography, Malcolm describes his emotions and his circumstances during his stint inside, but he skimps on the prison environment and what his day-to-day life was like. As I would learn later, the autobiography, while an inspirational text, was predominantly written by Alex Haley, who had interviewed Malcolm multiple times in the early 1960s for magazines such as Playboy and The Saturday Evening Post. The two men had made some headway on the book, but as scholars such as Keith Miller have pointed out to me, the autobiography is far more Haley’s version of Malcolm’s voice than it is Malcolm writing about himself. Vital parts of Malcolm’s time in prison are left out, including the deep friendship he had with Jarvis while at Norfolk and the correspondence between them. Recognizing these omissions, I tried in my book to prioritize primary documents like this poem, which is 100% Malcolm — unfiltered and unedited.

Norfolk was far from a typical prison. Completed in 1931, its layout resembled a college campus. The visionary behind the prison’s philosophy, Howard Belding Gill, wanted the institution to simulate a closed society. “One thing we are apt to forget,” Gill explained, “is that unless a man is in [prison] for life, he goes out again and what you make him in prison is what he is when he gets out.”

The Norfolk colony was considered the most progressive U.S. prison institution of its time. When Malcolm was transferred there in March 1948, it published its own biweekly newspaper and boasted a 12-member orchestra, a school program developed by an MIT-trained educator and a nationally recognized debate team that had defeated Harvard, Brown and even schools as far away as Oxford. Its library was so well stocked that Malcolm, from the beginning of his sentence, pleaded with his half-sister Ella to get him transferred to Norfolk. “My only reason for wanting to go,” he wrote to her in December 1946, “is the library.”

And what a library it was. At one point, the collection reached over 15,000 volumes, most of them donated by Massachusetts state Sen. Lewis Parkhurst. Dubbed by many the “Father of Norfolk,” Parkhurst had made his fortune as a textbook publisher, and when he passed away in March 1949 — the same year Malcolm wrote the poem — he bequeathed the rest of his collection to the colony. Parkhurst was an avid traveler, too, visiting Cairo with his family, and his broad interests were reflected in his library. Parkhurst’s collection could have been the start of its own university.

Malcolm, via Haley, rather begrudgingly mentions Parkhurst in his autobiography. “Norfolk Prison Colony’s library was one of its outstanding features. A millionaire named Parkhurst had willed his library there; he had probably been interested in the rehabilitation program.”

Malcolm and the other 800 or so incarcerated men at Norfolk were allowed to peruse the library shelves rather freely. It was because of Parkhurst’s broad interests in religion and history that Malcolm encountered dozens of books, including ancient Persian poetry by Hafiz (“The Rubaiyat of Hafiz”), Omar Khayyam (“The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam”) and Saadi Shirazi (“Gulistan”).

“I’m a real bug for poetry,” Malcolm wrote to his brother, Philbert, from Norfolk in February 1949. “When you think back over all of our past lives, only poetry could best fit into the vast emptiness created by man.” Indeed, he starts this letter with quatrain 31 from “The Rubaiyat of Hafiz,” translated by Launcelot Alfred Cranmer-Byng. Here are the final two lines, a reflection of prison’s lonely struggle:

So to the skirts of solitude I cling,

Lest friendship lure me to an evil end.

From Shirazi’s “Gulistan,” Malcolm quotes a longer passage, blending his newfound faith in the Nation of Islam with his love for poetry:

Allah did not forget thee in that term.

When thou wast but the buried, senseless germ:

He gave thee soul, perception, intellect

Reality and speech and reason circumspect;

By him five fingers to thy fist were strung

And thy two arms upon thy shoulders hung.

O graceless one! what cause has thou to dread

Lest he remember not thy daily bread?

The quote Malcolm uses to start a new letter to Philbert the very next day reveals a different kind of struggle. It’s from “The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam,” translated by Edward FitzGerald:

Indeed the Idols I have loved so long,

Have done my credit in this World much Wrong:

Have dropped my Glory in a shallow Cup,

And sold my Reputation for a song

Though he doesn’t state this directly, Malcolm is surely thinking of the musicians (“Idols”) he had worshipped in the past. Whether shining shoes as a teenager outside a Boston dance hall, running errands for jazz musicians, dancing the lindy as brass bands blared from the stage or memorizing the schedules of Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Lionel Hampton and Billie Holiday, music, especially jazz, was a major part of Malcolm’s young adulthood. But as he wandered deeper into the Nation of Islam, he began to see those musicians differently. Many of them did not have faith or a greater purpose. They smoked, drank, criticized those who had found religion, slept around and then went home, too busy to see the “vast emptiness” they were living. Malcolm had lived that fast, turbulent lifestyle, and it had led him to prison.

Nevertheless, he kept in touch with Hameed and Jarvis while incarcerated. The year 1949 was a difficult one for Jarvis. In February, he wrote to his parents that he no longer wished to carry on living. “Please take under consideration,” Jarvis wrote to his mother on Jan. 30, 1949, “that there comes a time in every man and woman’s life, when they reach the cross roads of life. The road that goes to the left is bad and that to the right leads to good. At the present time I find myself at that cross road.” Jarvis had lost his wife, Hazel Register, in May 1948, and even though his two young boys were now living with his parents, Jarvis felt he didn’t have anything to offer them. Hazel had struggled with being a mother, and Jarvis conveyed that to his own mother.

Hazel wanted to do things for [our boys], and often thought of them. But now she’s lying six feet deep. On the other hand, she probably is doing them more good, by being where she is, than I could ever do being in prison. I have often thought I would much rather keep her company than to give these people two or three more years of my life.

These sentiments alarmed prison officials, who read all correspondence going in and out of Norfolk. For the rest of 1949, Jarvis’ letters were typed up and kept on file — which is the reason we have Malcolm’s poem at all — and he was required to go to counseling. In his February 1949 letter to Philbert, Malcolm mentions that “Jarvis was examined by the psychiatrist (I murdered that spelling yesterday). It all stemmed from a letter he wrote to his family to try and interest them in speeding up his release.”

As Jarvis struggled with finding a renewed sense of purpose, he talked with Malcolm. Over those months in 1949, Malcolm explained to Jarvis what the Nation of Islam offered — a safe haven from a system stacked against them — and Jarvis took it all in. Together, the two men shared their thoughts on faith.

An important visitor for both men during this year was Hameed, who visited Jarvis at least 12 times at Norfolk between 1949 and 1950. Hameed was an Ahmadiyya Muslim and had previously given Jarvis and Malcolm prayer books. Between Malcolm encouraging him to join the Nation of Islam and Hameed’s steady religious presence, Jarvis shook off his suicidal thoughts. Norfolk’s visitor policy allowed for dual visits, so there were times when both Jarvis and Malcolm met with Hameed together. The content of their conversations is unknown, but one thing is certain: They shared a love of music.

By July 1949, Jarvis felt comfortable inserting the poem from “Red Little” in a letter to Hameed. Malcolm had long been fascinated with music and poetry. At Norfolk, he explored his love of language, finding joy in the etymology of a word — chiming with his self-consciousness at misspelling “psychiatrist” — and deploying varied imagery in his own letters.

In a March 1950 letter to a friend, he expressed his need for words. “Know that each letter from you is dearly sought, for your humble words of Truth are as drops of Dew to this weary Traveler on the hot sands of a dry desert. … May your Fountain Never Run Dry.”

Malcolm’s poem stands as a symbol of his resilience during dark times. At Norfolk, he would read so much at night that he would need glasses for the rest of his life. Whether memorizing vocabulary from the dictionary, absorbing etymological principles from Frederik Bodmer’s “The Loom of Language” or reading poetry from ancient Persian poets, Malcolm had an insatiable desire for the written word. “I have often reflected upon the new vistas that reading opened to me,” he explained to Haley in his autobiography. “I knew right there in prison that reading had changed forever the course of my life. As I see it today, the ability to read awoke inside me some long dormant craving to be mentally alive.”

Despite everything I had found over the years related to Malcolm’s time in prison, by 2020 I was about to give up on my book. I had been wrestling with doubt. Was the book necessary? If so, was I the right person to reveal this information? Perhaps I should hand it all over to someone else and move on? When Les and Tamara Payne’s “The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X” came out to glowing reviews, sweeping awards and propelling Malcolm back into the national conversation, I was initially happy to read so much more new content on the man, but as an author I wondered if the market wanted “another Malcolm book.” With King, it had been different; the finer points of his life had needed a dusting off. But with Malcolm, there were now two award-winning, full-length biographies to read. Wasn’t that enough?

It was at this moment that I decided to share my research with the people I believed needed to know it most: Malcolm’s family.

Through an intermediary, I connected with Malcolm’s daughter, Ilyasah Shabazz, and shared what I had learned about her father’s time in prison. She loved it, especially since she was putting the finishing touches on her own young adult novel, “The Awakening of Malcolm X,” which she co-wrote with Tiffany Jackson. Shabazz cherished learning about Malcolm’s debating performances at Norfolk and what he read. “I want to know everything he read,” she said. But it was the poem that affected her the most. She and Tiffany had felt their novel was missing that extra “something.” So they asked if they could use it. I quickly replied, “Of course!” After all, it was far more fitting that Malcolm’s family should have it.

Sharing my research was satisfying, but Ilyasah wanted more. “Keep going,” she said.

So I did.

Previous Malcolm biographies did him a disservice by skimming over his period of incarceration. Behind prison walls, especially at Norfolk, he developed his mind and his faith, honing his love for language. It was a formative time, best understood by considering what he read and appreciating what he wrote. Malcolm’s lone poem is a testament to the civil rights leader’s transformation.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.