Naked before the brittle sensitivities of public opinion, there are certain themes in Turkey that the academy can touch upon but popular culture must never. For starters are the obvious elephants: the fate of the Armenians since 1915 and of the Kurds, with certain lofty exceptions, since 1925. But secondary taboos also persist. Chief among these is the destruction of Istanbul’s centuries-old non-Muslim minorities in the decades after the republic was founded.

Remembered by reserved elders but unconsidered by most of Turkey’s small and silver screens are such incidents as the Wealth Tax of 1942, which stripped most Christians and Jews of their savings and property under the fog of war, or “the events” of Sept. 6-7, 1955, when state-sponsored riots against Istanbul’s minorities destroyed 5,317 businesses, 4,214 houses, 1,004 offices, 73 churches, 26 schools, one synagogue and one monastery. These are issues at best for old Beyoğlu bookstores or Boğaziçi University colloquiums, held preferably around 2008, when Erodgan was still celebrated by liberals in Turkey and Europe alike.

That’s what’s so remarkable about Netflix’s latest Turkish production, “The Club” (Kulüp). On the surface, it’s but another highly stylized period drama, a cheeky peak into 1950s Istanbul as it races toward Cold War modernity. Glorified are not merely the slick new nightclubs, after which the show is named, but the automobiles, radio broadcasts and televisions, too. In addition to corpulent clouds of cigarette smoke, sex and technology fill the air.

Dig a little, however, and “The Club” has far more to say about postwar Turkey than it does about makeup and contraceptives. The show’s protagonist, after all, is Matilda, an almost middle-aged Sephardic woman who has been released after 17 years in prison. Freed during a general pardon that patently excluded “communists, spies and repeat offenders,” she nervously approaches her native Jewish community of Galata, Istanbul’s most famous non-Muslim quarter, after her release.

“I want to go to Israel,” Matilda stoically tells “Monsieur David” in Ladino, combining the Sephardic Jewish community’s charming use of French honorifics with the 15th-century Spanish they kept alive for nearly half a millennium in Ottoman exile.

“But we’ve been here for 400 years,” he responds. “This is our homeland. We’re still a big family here in Kula,” he tries to reassure her, using the old word for Galata, the ancient Genovese quarter whose iconic 14th-century tower still dominates the Istanbul skyline.

“I have no family,” comes her deadpan reply.

What unfolds next is one of the most interesting plot twists in recent Turkish television. Think of a Hallmark special about the Japanese internment camps or a PBS history of white flight to the suburbs. America’s vaunted self-criticism notwithstanding, no country likes to air its dirty laundry. This is what makes “The Club” so compelling. We soon learn why Matilda was sent away: for murder. And not over any typical “shoot-the-cheating-bastard” vendetta but for killing the only lover she had ever had, the father of her unborn child, in cold blood.

Of course, it’s more complicated than that. For Matilda’s story is set against a backdrop of war, expropriation and camouflaged ethnic cleansing. The first mainstream production of any kind, to this author’s knowledge, to broach the disastrous Wealth Tax, “The Club” places this terrible chapter in Turkish history at the forefront of Netflix’s latest hit. Though she was once a happy young girl from a prosperous family, Matilda’s life is ruined at a stroke by the notorious 1942 law.

“This is a law of revolution to eliminate the foreigners … and give the Turkish market to the Turks,” Prime Minister Mehmet Şükrü Saracoğlu, the architect of the tax, notoriously said at the time. It succeeded beyond the minister’s wildest dreams. Under the ruse of punishing war profiteers, a special commission assessed Armenian property at 232% of its real value, while the Jewish and Greek properties were assessed at 179% and 159% respectively, with a demand that the tax be paid in cash. For those who failed to make this arbitrary and exorbitant payment, the family breadwinner would be shipped off to die in the work camps.

Though Matilda’s father liquidates the family business to pay it, he and her brother are still packed away. “They worked them to death,” Matilda later tells her daughter, “which was the whole point.”

Despite following the “law” to the letter, her father, it turns out, had been denounced by none other than Matilda’s secret lover, his most trusted employee, an ambitious Muslim villager who then hoped to “inherit” the family business. That many of Turkey’s richest families today began their ascent after “acquiring” Christian and Jewish businesses at bargain-rate prices around 1942 makes this dangerous territory indeed. Up on the roof, where the tender young lovers had once necked while tending the pigeons, Matilda shoots the conniving traitor in cold blood. Who cared if she was pregnant? Muslim or Jew, man or woman, honor is honor. This surely anyone in Turkey can understand.

Released after 17 years, Matilda is determined to make a fresh start of it, albeit in the nascent state of Israel. The Turkish Republic, after all, has given her nothing but death and betrayal. But what about her daughter, implores Monsieur David, who was entrusted with Matilda’s secret offspring all those years ago.

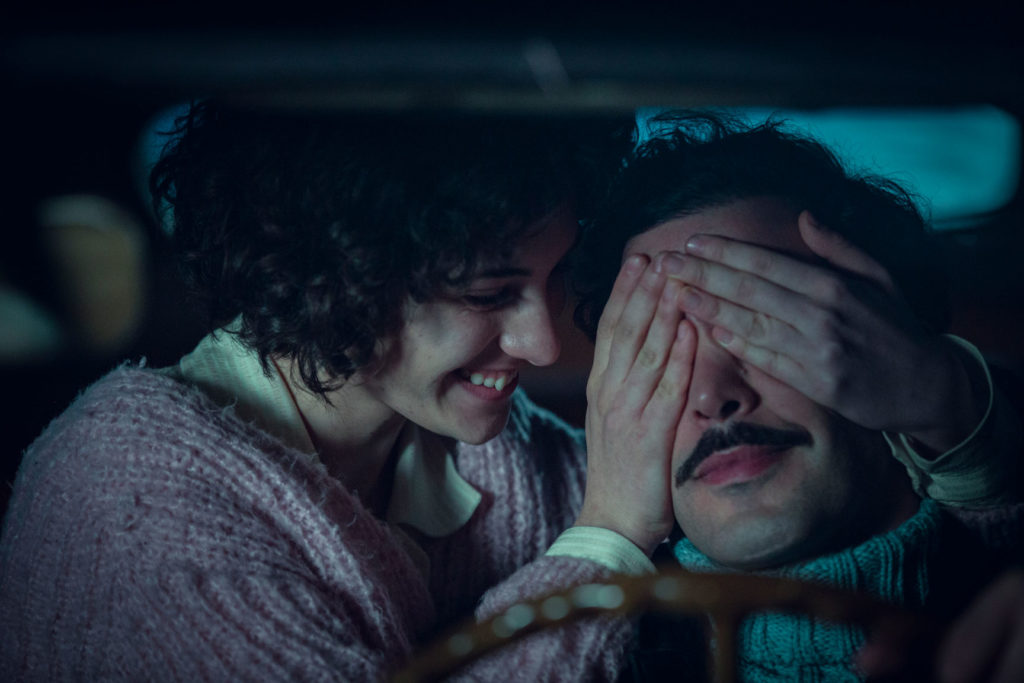

Rachel, it turns out, is a beautiful and spirited young woman, not unlike a younger version of her mother. Perilously, she too is on the verge of falling for a young Muslim buck, Fıstık İsmet, a dashing nihilist cabbie and mustachioed rebel without a cause. “They’ll always sleep with non-Muslim girls,” bemoans Tasula, a Greek friend of Rachel who’s also in love with İsmet and dances at the nightclub where Matilda will soon be forced to work, “before running home to marry a Muslim girl.”

Such is the multiple force of the show’s often razor-sharp writing. Not only does it touch on all the timeless themes of Turkish television — lust, betrayal and revenge — it also hits on more contemporary taboos: class struggle, ethnic conflict, the sexual revolution, gender violence and, above all, Istanbul’s ancient religious plurality, a delicate mosaic all but destroyed by the Kemalist republic.

This is the melee that Matilda is thrust back into. When Rachel is arrested for assault and vandalism — she and Tasula were caught breaking into the nightclub to retrieve Tasula’s papers, which her sexually abusive boss kept locked away — Matilda rushes down to the station with Monsieur David. Given the latter’s stature in the community — one of many nods to a vanished coexistence — Çelebi, the sordid manager who sexually exploits many of the young women at the club, agrees to drop the charges. Until he spots Matilda. “You’ll work for me at the club until Rachel’s debt is paid,” he cruelly informs her. Mysteriously, now, the real fun begins.

Enter the wild and swinging nightlife of late 1950s Istanbul. On the one hand, it’s an all-too-familiar sight: beautiful people in beautiful costumes sipping bottomless drinks — where have we seen this before? For those in it for the set design, you will not be disappointed. Any well-crafted re-creation of mid-century Istanbul, before the cranes and nincompoops took over, is manna for those aesthetes suffering silently in the present. This was not just Europe, scream the luscious street scenes unfolding along Istiklal Avenue; it was our Europe.

But “The Club” also offers a biting social critique. For the show is less about the arrival of cocktail modernity to Istanbul — that had been there long before — than about the Turkification of cocktail modernity, i.e., a pincer movement by Kemalist state and society to substitute good secular Muslim Turks for Istanbul’s Greeks, Jews and Armenians. When the owner of the club, Orhan, a well-to-do “white Turk,” is named “Turkish Businessman of the Year” by the local Chamber of Commerce, he’s presented with one condition: fire his entire non-Muslim staff. “But who will replace them?” asks his manager in bewilderment. “The only people who can possibly do their jobs are other non-Muslims.”

“The country is changing,” replies Orhan stoically. “The non-Muslims will have to realize that.”

By confronting these demons in broad daylight, “The Club” is far braver and much more revealing than most Turkish television in recent years. Like “Bir Başkadır,” Netflix’s breakaway Turkish hit from late 2020, it confronts crucial aspects of Turkey as it is, not as it wants to be. Which is difficult for mainstream television to do, much less turn a profit from. To their credit, Turkish audiences are much braver than producers give them credit for. “The Club” is not only the current talk of the town; so far, it’s received enormously positive reviews across the board.

To be sure, the show is still peppered with unfortunate platitudes. Burası still Türkiye (a gesture akin to a shrug that translates as “This is Turkey”). Least appetizing of all may be the show’s male worship, a disease that plagues too many post-warrior cultures. This is unfortunate, given that the show was co-directed by a woman, Zeynep Günay Tan. But not all that surprising. It’s difficult to uninvent the wheel when you’re hurling downhill.

Equally cliché, if depressingly accurate, is the tendency for characters to cower before their superiors while sticking it to their underlings, a relentless theme in Turkish television in everything from “Behzat Ç,” Turkey’s greatest policier, to “Aşk 101,” another recent Netflix hit. Such is the case with Çelebi, the show’s dark horse, whom we do not (yet) sympathize with. He’s a rapacious scoundrel — thieving, abusive and exploitative of anyone less powerful than himself. Yet here and there we catch glimpses of a spurned and lonely man. Perhaps he is not beyond redemption.

Though “The Club” deserves kudos for approaching mid-century Istanbul from a striking and tragic Sephardic perspective, its most heartening aspect may be the smaller moments of solidarity among the city’s myriad characters, each struggling in their own way to keep their head above water, whatever their religion or ethnicity.

One afternoon, while passing through a working-class Galata courtyard, Matilda stops to listen to a record playing from an upstairs window, a wailsome old Sephardic song. She begins to tear up. One of the nameless janitors from the club, a sweet young Muslim lad still fresh from Anatolia, chances by. “What a beautiful song,” he says to Matilda. “It reminds me of the lullabies my mother would put us to bed with as children.”

“It’s an old Sephardic song,” she tells him, to which he looks at her quizzically. “Sephardic,” she repeats, “like the Jews who migrated here hundreds of years ago. Like me, that is.”

“Like us, you mean,” he replies with a humble smile.