As the chaotic 2024 election cycle unfolds, the women of pop music are keeping us on our toes. Lana del Rey has just secretly married Jeffrey Dufrene, a swamp boat tour guide based in the deeply red Louisiana Bayou. Chappell Roan, the new queer pop phenom on the scene, has canceled major appearances after stoking liberal rage for her refusal to endorse either major candidate. Beyonce has not officially endorsed Democratic Party nominee Vice President Kamala Harris but has given the campaign permission to use her anthemic hit “Freedom” as its official song. She also threatened the campaign of Republican Party nominee Donald Trump with a cease-and-desist order for its own use of the same song.

Meanwhile, Taylor Swift — perceived as the crown jewel of celebrity endorsements this season — remained mum on the race long enough to inspire rabid speculation. Did her willingness to be seen hugging fellow Kansas City Chiefs superfan Brittany Mahomes, who had recently liked a post on Trump’s Instagram page, at the U.S. Open men’s tennis final on Sept. 8 indicate Swift’s own leanings? Was Swift keeping quiet based on the assumption that a Democratic endorsement would do more to fire up the right than aid the left? Questions abounded up until Sept. 10, as Harris and Trump left the stage after their first and only debate, when Swift posted a picture of herself holding one of her famous cats on her social media platforms, officially endorsing Harris:

I’m voting for @kamalaharris because she fights for the rights and causes I believe need a warrior to champion them. I think she is a steady-handed, gifted leader and I believe we can accomplish so much more in this country if we are led by calm and not chaos. I was so heartened and impressed by her selection of running mate @timwalz, who has been standing up for LGBTQ+ rights, IVF, and a woman’s right to her own body for decades.

She signed off, “Taylor Swift, Childless Cat Lady,” a reference to Republican vice presidential nominee JD Vance’s earlier snub of Harris and her female peers as “childless cat ladies who are miserable.”

Many have described the endorsement as picture-perfect. “The timing on it is exquisite. The wording of it is flawless,” MSNBC anchor Lawrence O’Donnell effused. “Her endorsement hit all the best practices,” echoed Ashley Spillane, the author of an August 2024 study by the Harvard University Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation about the impact of celebrities on civic engagement, in a conversation with the BBC.

In a race that is projected to come down to a handful of swing states — including the one where Swift grew up, Pennsylvania — it’s true that Swift’s cultural dominance could move the political needle. Her Instagram post has received over 11 million likes, and the custom URL to vote.gov that she shared on her stories led 405,999 visitors to the site in 24 hours. Excitement surrounding this possibility has solidified a sense that celebrities — particularly musicians, and particularly Swift — are playing a larger role than usual in this election.

Confirming that perception is tricky, given that there is no way to measure the direct impact of an endorsement on the number of votes the endorsee ultimately receives. While we cannot make definitive statements about how consequential Swift’s endorsement will be, we can say that it is among the most controversial in modern American history. The pop star’s position at the helm of Democratic endorsements brings her glitter-infused brand of white feminism to the fore, not so much raising the question of how it will impact this presidential race but rather what it says about white women’s politics.

Swift is not the first celebrity who has had the potential to sway a race. Since mass media made celebrity as we know it possible, famous entertainers have interacted with politics. Frank Sinatra was a pioneer of such commingling, famously rewriting and performing his hit “High Hopes” to support the John F. Kennedy campaign in the tight election of 1960. Many analysts believe Oprah Winfrey’s endorsement of Barack Obama was critical in his victory in the 2008 Democratic primary against Hillary Clinton. Upon President Joe Biden’s withdrawal from the race this summer, British pop star Charli XCX’s viral tweet, “kamala IS brat,” garnered over 55 million views on X. A reference to the name of her sixth studio album, which was not just a collection of songs but a summer trend embracing messy and hedonistic femininity, the tweet inspired the Harris campaign to launch by replacing Biden’s banner with a graphic mimicking the lime green and black aesthetic of the album art, reading “kamala hq.” On Tuesday, rapper Eminem appeared at a Detroit rally for Harris. He introduced former President Barack Obama, who then recited lyrics from Eminem’s “Lose Yourself.”

The difference with Swift’s endorsement is the fact that there was even a question surrounding the way it would go. The musician has periodically thrown her support behind Democratic candidates for over five years now, but every election cycle seems to bring the same possibility that she may have switched sides, or she may simply not care in the way many onlookers want her to. To this day, however absurdly, we watch Swift the way we watch the returns on election day. In fact, NBC periodically publishes polls of Swift’s approval ratings with registered Democrats and Republicans.

How did Swift come to occupy such embattled territory? The answer rests in her country roots and the repressed sensibility that defined her early years as a pop star, an innocent persona only available to a small swatch of thin, middle- and upper-class white women in the United States. Whether or not she wants to be claimed by both sides, Swift performs gender in a (mostly) nonthreatening way that ultimately reinforces patriarchy and makes her broadly palatable. In other words, though she has certainly experimented with more risque personas (or “eras”) as she has grown up in the public eye, she has maintained her “good girl” image both onstage and off. (“Sweet” is a common adjective used in descriptions of her by those who know her, and those who feel like they do.) While there is nothing inherently wrong with these traits, the pressure to be “good” often precludes challenging oppressive norms.

Swift has been aware of her unique position from the start. On Nov. 11, 2008, a week after Obama won his first presidential election, she released her second album, “Fearless.” With hit songs like “Love Story” and “You Belong With Me,” it would become the bestselling album in the U.S. over the course of the next calendar year — Swift’s first. In a period of financial crisis, public figures like Swift and Obama provided fairytale narratives of underdogs triumphing against the odds. In her first Rolling Stone cover in March 2009 — “Taylor Swift: Secrets of a Good Girl” — she reflected that atmosphere, saying, “I’ve never seen this country so happy about a political decision in my entire time of being alive. I’m so glad this was my first election.”

In time, Swift switched out platitudes for an even more restrained version of apoliticism. In 2012, she told a Norwegian journalist, “I just figure I’m a 22-year-old singer and I don’t know if people really want to hear my political views. I think they just kind of want to hear me sing songs about breakups and feelings.”

With Trump’s political ascendance in 2016, Swift’s noncontroversial nature became a controversy. White supremacists were claiming the pop star as their “Aryan goddess.” Swift has said she did not know this, but she certainly knew she stood to alienate untold fans by speaking out against Trump, or entering the fray at all. As Clinton tried to become the first female president — in one of the more star-studded campaigns in recent history, featuring Katy Perry, Lady Gaga, Ariana Grande, Rihanna and Beyonce — Swift remained silent. (Debate has since swelled surrounding the possibility that Clinton’s robust celebrity support did more to stoke anti-elitist sentiment on the right than fuel the left.)

Finally, in 2018, Swift found a way in. She endorsed the Democratic candidates Phil Bredesen and Jim Cooper in the midterm elections in her home state of Tennessee, foregrounding her opposition to Republican Senate candidate Marsha Blackburn in an Instagram post:

Her voting record in Congress appalls and terrifies me. She voted against equal pay for women. She voted against the Re-authorization of the Violence Against Women Act, which attempts to protect women from domestic violence, stalking, and date rape. She believes businesses have a right to refuse service to gay couples. She also believes they should not have the right to marry. These are not MY Tennessee values.

A major Netflix documentary, “Miss Americana,” released in January 2020, later allowed fans behind the scenes of this decision, capturing a tearful Swift in conversation with her team, saying she wanted “to be on the right side of history.”

The move infuriated the right, as have Swift’s periodic Democratic endorsements since. It also aggravated some on the left, who could not let Swift off the hook for her 2016 silence and pointed out how glaringly her feminism lacked awareness of her white privilege. The possibility of the endorser gaining more than the endorsee set in as an element of Swiftian politics, syncing up with a broader cultural discussion of performative activism that arose during the Black Lives Matter protests of summer 2020. (In a message to her fans that June, the New Zealand pop singer Lorde wrote, “One of the things I find most frustrating about social media is performative activism, predominantly by white celebrities (like me). It’s hard to strike a balance between self-serving social media displays and true action.”)

Apparently, however, Swift’s post moved a huge number of fans who existed somewhere between those two sides: 169,000 people registered to vote in Tennessee within 48 hours of Swift’s first endorsement. Blackburn still won, but Swifties now had politics.

As of the current election cycle, Swift has had the bestselling album of the year seven times over. Her fame is unprecedented. Her worldwide Eras Tour, which is slated to end in December, has made her a billionaire. The perception of relatability and authenticity that played a major role in launching her to pop culture dominance is now harder for Swift to maintain. Still, her fans are unwavering. A group called Swifties4Kamala (unaffiliated with Swift) with nearly 200,000 followers has become an active force, phone banking, distributing literature and registering voters. They intentionally merge Swiftian lightness with serious politics. The information they provide, for example, comes with section titles taken from Swift’s lyrics.

The timing of Swift’s endorsement was not as flawless as it was fascinating. In August, Trump had posted an AI-generated image of the star as Uncle Sam endorsing him on his social media platforms. Swift addressed the fake image early in her post, writing, “It really conjured up my fears around AI, and the dangers of spreading misinformation.”

“Her compulsion is really interesting,” Ryan Skinnell, an associate professor of rhetoric and writing at San Jose State University, told New Lines via email. “It implies that she wanted to stay neutral, and if Trump hadn’t misrepresented her, she would have kept quiet.” Swift walks a delicate line in the post, making clear that she has been compelled by the threat of Trump as much as (or possibly more than) inspired by Harris. “Presumably that allows her to stay nonpartisan because it wasn’t really the virtues of Harris’ platform (though she agrees there are virtues) that tipped her over the edge; it was the dangers of Harris’ opponent,” said Skinnell.

Skinnell situates Swift’s strategy in the context of a culture “particularly primed” for negative partisanship — a mode of engagement in which opposition to one candidate is more important than support for another. “Childless cat ladies amplify Harris’ platform a little (she’s pro-choice, a woman and a feminist, Walz is a cat owner, etc.),” he told New Lines, “but they amplify anti-Trump/Vance views a lot (they hate women! cats! abortion rights!).”

Trump’s fanbase certainly took note: NBC reported that 47% of Republicans said they viewed Swift negatively days after her endorsement. That number was at 26% in the fall of 2023.

“It just seems like that whole conversation is a bubble that really doesn’t affect how people vote or think,” said Gina Arnold, a former rock journalist and author of “Half a Million Strong: Crowds and Power from Woodstock to Coachella” (2018). Arnold is skeptical about the concrete political influence a pop star like Swift can have, especially when meme-fueled fights far removed from policy concerns are moving the polls. Even in the 1960s, when popular musicians and their fans were forcefully united in their anti-war leanings, for example, no amount of entertainment industry influence halted the Vietnam War.

We cannot necessarily blame Swift for taking part in a culture dominated by praise and blame. However, it is worth noting that the pop star’s brand tends to be rooted in a personal version of this very mode. Swift is known, firstly, for writing great love songs and, secondly, for clapping back at anyone who thwarts those stories. She makes art of “shaking off” her “haters.” She snarls, “Look what you made me do.” This intense focus on slights to a woman’s otherwise good character — the need to defend that perceived purity — is a hallmark of the limited scope of white feminism. In this mindset, a privileged white woman fails to acknowledge that less-privileged women carry additional burdens — that her struggles are relative to, not representative of, all women.

Swift’s actions are also noticeably restrained. “Endorsement is probably more meaningful, and only slightly, if it’s done in a more active way,” Arnold told New Lines. “Olivia Rodrigo talking about a single issue — abortion — on stage and having information booths in the lobby, with an audience that is entirely young women, seems like a far more influential way to go about it,” said Arnold.

The great irony here is that, as of 2024, Swift’s obvious efforts to remain moderate have made her satanic in the eyes of the right. Trump’s “I HATE TAYLOR SWIFT” post following her endorsement is but the tip of the iceberg of the current GOP sexism hitting Swift. Critic B.D. McClay has referred to this phenomenon — in which right-wing commentators have painted Swift as a middle-aged “slut” — as “Taylor Derangement Syndrome.” McClay writes, “Taylor is a normal person and that’s why she’s a Democrat. That’s the reality created by people who make weird Sonnenrad memes trying to pump up Ron DeSantis. You lose the normal people.”

In other words, it does not bode well for the Republican Party that it can no longer count the apolitical “good girls” among its ranks.

Swift’s public relationship with Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce has, in Swiftian phrasing from her hit “Bad Blood,” rubbed “salt in the wound” over the last year. Far from her liberal-leaning romantic partners (who tended to have British roots) who preceded him, Kelce is a conservative dream. Paired with Swift, his highly normative masculinity could have looped the singer right back to the start, where she was a country darling just longing for a football star. (See: 2008’s “You Belong With Me.”) Swift is still surprisingly close to that persona, but her distaste for Trump has added a twist so alarming to right-wing culture warriors that many have decided the whole relationship is a scam. How could such an “American” romance not come with a MAGA hat? Some on the right, such as Fox News host Jesse Watters, suspected it was a CIA psyop designed to infuse the NFL crowd with Swift’s support for Biden. But what if it’s just that a very privileged white woman who loves football, and has never felt very threatened by the Republican Party, now feels that even someone like herself is in danger?

Psychic battle surrounding the political moves of American ingenues is not a new phenomenon. For comparison, we can look to other young white women who navigated similar pressures to conform to conservative gender norms.

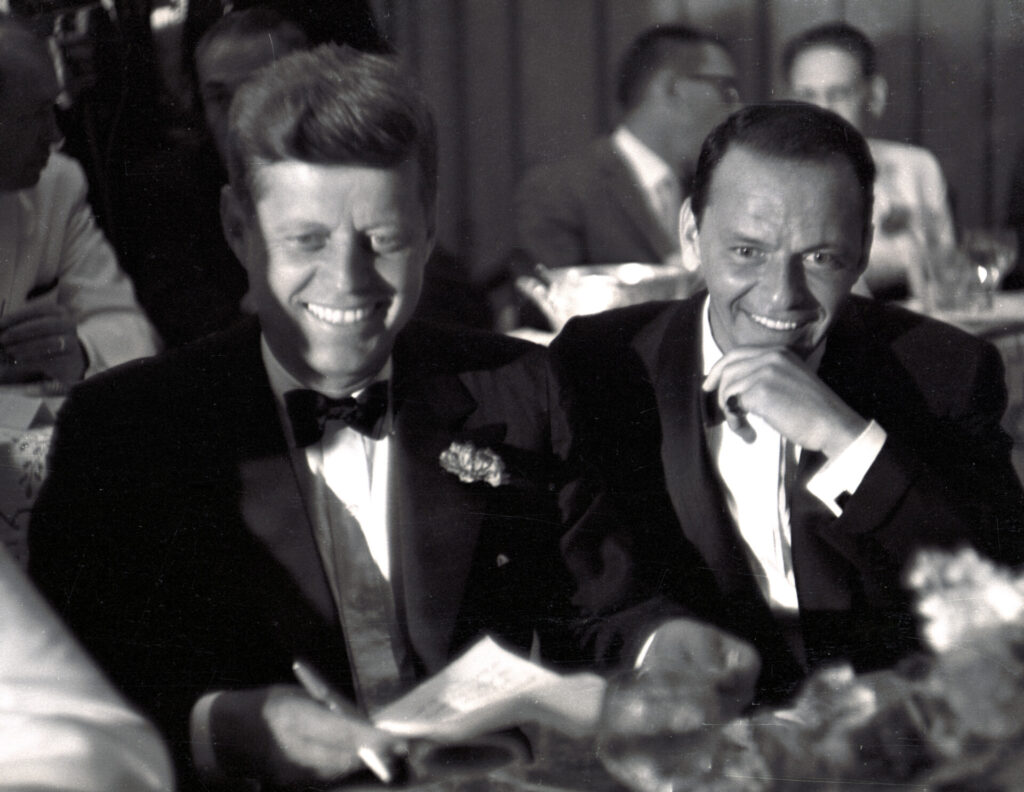

Marilyn Monroe provides an intriguing starting point in the postwar era. Her infamous 1962 performance of “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” for Kennedy at his Madison Square Garden birthday celebration was not an endorsement, but it was an early example of a famous white woman interacting with a politician on the national stage. Appearing in a skintight sparkling gown, Monroe embodied the hypersexualized beauty expected of starlets of the era. Her performance fueled speculation about her rumored affair with the president, adding more glamor and intrigue to JFK’s image but ultimately reinforcing the sexist status quo. “I can now retire from politics after having had Happy Birthday sung to me in such a sweet, wholesome way,” said Kennedy when he took the mic at the end of the show. Of course, he was being ironic; he was emphasizing the opposite, how entirely unwholesome Monroe seemed. And that was the reductive trap white female entertainers found themselves in: the Madonna or the whore. Choose one, never both.

That same year, however, a much different kind of woman was on the rise: Joan Baez. As the unrivaled star of the folk music revival, she appeared on the cover of Time Magazine in late November 1962 at the age of 21. Far from the iconoclast she became, Baez had kept her progressive politics rather quiet during her ascent to the mainstream. She was known for her sparkling soprano renditions of the Child Ballads, a body of traditional English and Scottish songs carried over the Atlantic well before her time. She often wore loose white dresses and averted her gaze as she sang, gaining a reputation as folk’s Madonna. However, in the Time article, she cleared up any confusion about the kind of young woman she was. First of all, she was not white: Her father was Mexican. She detailed her experience of racism growing up in the 1940s and ‘50s. Furthermore, she spoke openly about her recent shows in the American South, where she was establishing a new precedent for mainstream entertainers with written clauses in each of her contracts insisting on integrated seating.

At that moment, Baez risked trading perceptions of her purity for something much closer to perceptions of Marilyn Monroe. But, much like Jackie Kennedy and other educated, self-possessed women who were gaining star power by the early 1960s, Baez managed to fuse the two options and model a kind of political womanhood that maintained enough normative sex appeal to keep the mainstream engaged — for a time, at least. Baez would become one of the leading female pop musician-activists of the 1960s, engaging consistently with the civil rights and anti-war movements. Many followed her lead: Mary Travers, Carole King, Judy Collins, Jane Fonda and more.

Swift’s political activities pale in comparison to these women, but in many ways, it isn’t a fair comparison. Multiple decades and massive change in the music industry separate her from a figure like Baez. “In the ‘60s and ‘70s, the suits would send out [artists and repertoire] men to scout out what the kids wanted to hear (buy). But in the ‘80s, they decided not to waste their time on that and just tell kids what to buy,” Kristin Hersh told New Lines via email. The frontwoman of the independent bands Throwing Muses and 50 Foot Wave, Hersh also published “The Future of Songwriting” this year. “They bought radio play, bought magazine covers, bought shelf space in record stores, etc. They bought attention,” she said.

This top-down approach coincided with a conservative backlash in the 1980s to the extent that pop womanhood lost much of the political edge it had gained in prior decades. By her debut album in 2006, Swift was poised to take the pop baton from Britney Spears — who did not wade into electoral politics at all in her heyday.

Swift has been the major white female star of the 21st century. She has modeled a kind of womanhood that contends with an extraordinary set of factors that her pop predecessors did not face: social media, Trump and the tensions of 21st-century capitalism that have divided the U.S. and put democracy in peril. Furthermore, as of July 2024, registration rates among voters between 18-29 had dropped significantly since November 2020, when the youth vote played a decisive role in Biden’s victory.

In this context, Swift’s evolution from country music darling to proud “childless cat lady” stands out. While it may seem unimpressive to some, never has a female star traversed so much of the political spectrum so publicly.

Male stars and co-ed bands are worth bringing into the mix. Again, those with folk and country aesthetics tend to find themselves embroiled in election season spats. Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” has anthemic qualities that — like the New Jersey working-class hero himself — code both red and blue. At a reelection campaign rally in Hammonton, New Jersey, in September 1984, in the months just after the song’s release, President Ronald Reagan boldly claimed the musician for the right, saying, “America’s future rests in a thousand dreams inside your hearts. It rests in the message of hope in songs of a man so many young Americans admire — New Jersey’s own Bruce Springsteen.”

Springsteen responded relatively quickly, telling Rolling Stone, “You see the Reagan reelection ads on TV — you know: ‘It’s morning in America.’ And you say, well, it’s not morning in Pittsburgh. It’s not morning above 125th Street in New York. It’s midnight.” Although he cited his disdain both for Republican co-opting of his music and for divisive politics in general, Springsteen refused to endorse any presidential candidates until he aligned himself with the Obama campaign in 2008. In the era of Trump, Springsteen has continued to endorse Democrats, most recently posting a video of himself sitting in an unnamed diner, explaining his support for Harris. In it, he compares the current level of division to the Civil War era and says, “Donald Trump is the most dangerous candidate for president in my lifetime.”

With all this in mind, it is easy to see how the weight of the world seems to have landed on Swift’s shoulders. There are no clear answers to the enormous questions she faces. Are there times when pop stars should pick a side, or should we respect the notion of music as a uniting force? What happens when a politically ambiguous star dips a toe in and makes a clear statement once in a while? Is that more or less impactful than stars who remain consistently engaged and clearly on one side? And when it comes to famous white women privileged enough to have honor to defend, should they do so in the name of feminism? Does the answer to that question change in the context of the white star supporting the first Black woman to run for president?

Finally, who’s to say an Instagram post can’t change the world in 2024? Opinions of media literacy aside, the reality is that truncated modern attention spans have reduced the ability of an already-disengaged public to engage in much more than the “vibes” of public figures. Tabloids, for what it’s worth, have reported that Brittany Mahomes is now questioning her public support of Trump after being “deeply bothered” by his expression of hatred toward her friend. Those who crave deeper engagement with policy may not like it but, for an indiscernibly large number of undecided, disinterested or disillusioned voters, defending Swift from Trump may be the only impetus to vote.

Given the shallow state of things, it feels tempting to romanticize decades in which political womanhood merged with pop womanhood to the point that politics, intelligence and sex appeal were of a piece. But Joan Baez herself refused to get involved with partisan politics until the 21st century. The same goes for Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan — two popular musicians to whom Swift has often been compared. There may be something in this notion of celebrities stepping back, not for the sake of their reputations but for the sake of democracy. “All that’s gold doesn’t glitter, right?” says Hersh. “So [I] hope that our future political and musical stars will not be stars at all, but a more egoless version of selfhood that serves their work. Luminaries don’t glow, life does.”

“Now the [music] industry has helpfully imploded and collapsed,” Hersh added. “It’s still buying attention (and record and ticket sales and radio play, etc.) but audiences are splintering into groups and finding what they love instead of being told what trends to like.” She sees reason for hope: “They’re listening through time and genre, becoming more discerning and less subject to manipulation.” If this is the case for young listeners, perhaps it is also the case for new voters.

Whether or not Swift has moved political needles, she has moved female pop music away from the two decades preceding her arrival, represented by Madonna’s “Material Girl” and Spears’ “Hit Me Baby One More Time.” When it comes to Swift and feminism, we must constantly remind ourselves that the bar was low when she arrived; she did raise it.

A case in point is that the top three songs on the Top 40 as of this writing — Chappell Roan’s “Good Luck, Babe,” Billie Eilish’s “Birds of a Feather” and Sabrina Carpenter’s “Please Please Please” — were all written by the singers who perform them, a trend Swift spearheaded in 21st-century female pop. Furthermore, all three of those singers are already breaking down conventional white womanhood in exciting ways: Roan with her drag aesthetics, Eilish with her gender fluidity and Carpenter with her downright hilarious take on ‘50s-style femininity. All three have chimed in on partisan politics already. And all three grew up in a world of Taylor Swift.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.