Salman Rushdie’s “Satanic Verses” happened to be published at a time when two very different Muslim communities were struggling to build and project their identity. One is of course Iran. But the other, far less recognized, was not Saudi Arabia, so often cited in connection with Iranian power, but British Muslims. Two British religious political activists traveled to Iran, expressing their outrage over the novel to officials, leading to the famous fatwa, which, 33 years on, resulted in a brutal attack on the author by a 24-year-old Lebanese American who repeatedly stabbed a writer he had not read, for a book written over a decade before he was born.

In the bigger picture of subversive writers, Rushdie does not top the list, and the novel in question is far from the most insulting writing on the Prophet Muhammad. Yet a bizarre confluence of events led to Rushdie’s being declared an enemy of Islam, with a sentence of death, by the Ayatollah Khomeini, keen to bolster Iran’s legitimacy at home and to export its ideology in the region. Khomeini died just a few months after issuing the fatwa.

This story was told in 2019 in a BBC podcast series, “Fatwa,” yet the British element has been curiously absent in the public debate since the attack — without a doubt aided by Iran’s doubling-down on the validity of the sentence and its blanket celebratory media coverage, which has directed attention in its direction. Kalim Siddiqui, who died in 1996, was a firebrand imam in the U.K. who, despite being Sunni, had a deep admiration for the Iranian revolution — as was common at the time — seeing it as a successful attempt to free Islam from Western domination: local Muslims overthrowing the Western-backed dictator, the shah. He began traveling regularly to Iran, meeting regime figures and even receiving funding for his own projects back in the U.K.

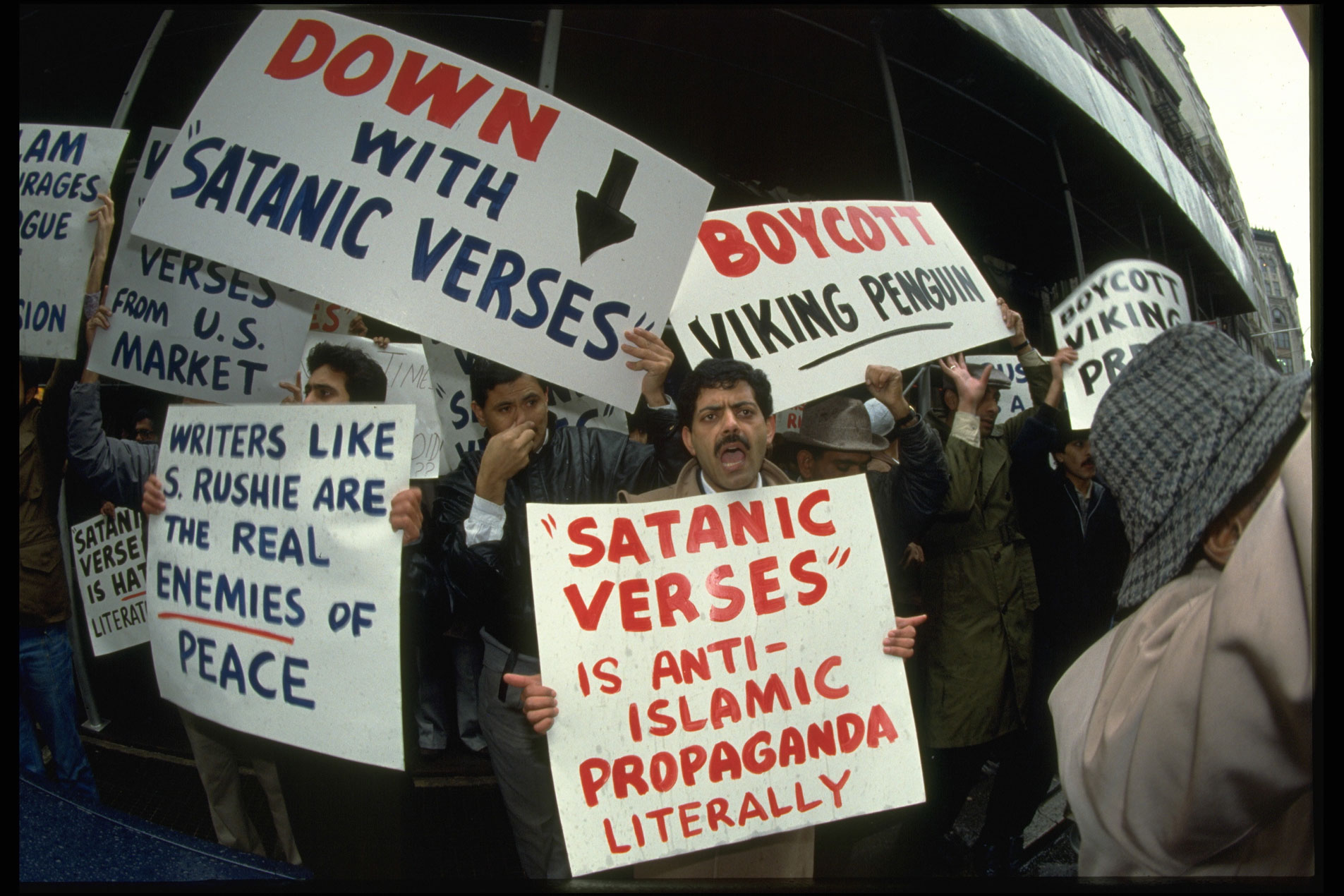

Chloe Hadjimatheou produced and co-presented the BBC’s “Fatwa” series, in which she describes the uncovering of this neglected aspect of the story. Fellow journalist Yasmine Alibhai-Brown knew the two British activists, Kalim Siddiqui and Ghayasuddin Siddiqui (no relation), who had whipped up attention to the novel in Britain by sending photocopies of the offending passages to mosques around the country, sticking up posters and generally fomenting the feelings that erupted in protests around the country, including attempts to burn the book, which, it turned out, wasn’t as easy to do as you might think. Prominent public figures — both Muslim and non-Muslim — politicians, writers, religious leaders among them, spoke out against Rushdie in the wake of the furor over the fatwa.

“I would not shed a tear if some British Muslims, deploring his manners, should waylay [Rushdie] in a dark street and seek to improve them,” Lord Dacre said to the BBC in 1989, after the fatwa was issued. Iqbal Sacranie, who later became secretary general of the Muslim Council of Britain, said: “Death, perhaps, is a bit too easy for him … his mind must be tormented for the rest of his life unless he asks for forgiveness to Almighty Allah.” There was not a single prosecution for incitement to murder despite the tenor of the protests that spread across the country calling for his death. Many regret this now.

Hadjimatheou spoke to Alibhai-Brown and heard the whole story. “But I couldn’t prove it,” Hadjimatheou later told me during a private chat, “until I dug around in the BBC archive and found Kalim Siddiqui on [the BBC radio program] ‘Beyond Belief.’” When he went to Iran in February 1989, Kalim freely described to the presenter how he met Iran’s foreign minister in the VIP lounge in an airport, telling him, “You’ve got to help Muslims.” The fatwa was issued later that day. The presenter asked him: “You feel proud of that?” And the answer was unequivocal. “Absolutely, yes.”

This was not the case for Kalim’s deputy, Ghayasuddin, who regretted his part in the affair. More archive digging yielded an interview with Ghayasuddin that confirmed his regret while corroborating the story of the trip to Iran. “We saw Dr. [Mohammad] Khatami, who was then minister of Islamic guidance, and when he saw Dr. [Kalim] Siddiqui, he went to greet him,” Ghayasuddin recalled. The minister and Kalim disappeared into a corner to chat, and when Kalim returned, Ghayasuddin asked him what they’d talked about. Kalim replied: “He is going to see Khomeini and he was asking my view about Salman Rushdie and I told him, you know, something drastic has to happen.”

Khomeini understood the opportunity at once. He was coming out of the humiliating end of the Iran-Iraq war, a bloody eight-year conflict he swore he would not lose; when he was pushed into making peace, he described it as “drinking a chalice of poison.” Legend has it that he never smiled again. He was looking for ways to re-establish his credibility as a leader in the face of defeat, project national strength and soothe his wounded pride. This opportunity to stand up for Muslims worldwide was perfect timing.

Khomeini’s project had not originally been overtly sectarian, in contrast to today, when Iran’s political activity such as rivalry with Saudi Arabia, interference in the Syrian civil war on the Alawites-Assad side and long-term support of Hezbollah in Lebanon is all framed in sectarian terms. In fact, he developed his ideas for his Islamic republic during his correspondence with the Sunni Pakistani imam Syed Abu Ala Mawdudi, founder of the Islamist Jamaat-e-Islami movement. This trend of developing the republic’s ideals in conjunction with Sunni scholars has continued: Current Ayatollah Khamenei translated the works of Muslim Brotherhood leader Sayyid Qutb’s books into Persian. Indeed, the revolution was not to establish global Shiite supremacy — the leaders knew such a goal would be difficult for a minority to achieve. Instead, they were seeking to establish a strong ummah, or Muslim nation, showing the world that Islam — not Shiism — was the force to be taken seriously. Khomeini therefore attached himself to what he might have considered politically unifying issues such as the cause of the Palestinians and the demonstrations by British Muslims against a British author that had spread to Muslim countries around the world.

But besides the brutal attack against Rushdie, there are other ripple effects of this long-ago decision, which initially aimed to use a literary scandal in the U.K. to boost the ayatollah’s image as a global Muslim leader.

“Rushdie united all Islamists,” Moustafa Ayad from the Institute of Strategic Dialogue told me over the phone, as he went through the responses on the extremist forums that he tracks daily. “I saw Islamic State supporters [do] ‘takbeer’ [for] the stabbing,” he said — referring to the ritual expression “Allahu Akbar” (“God Is Great”), used among other things to celebrate good news — “and IRCG [Iran Revolutionary Guard Corps] communities [do] takbeer [for] the stabbing.” In other words, “We are seeing opposite ends of the Islamist extremist spectrum coming together to celebrate the maiming of a world renowned author.”

The veneration of the attacker cut through all the divisions online, for both inter- and intra-sect disagreements. It had nothing to do with theology but instead with the success of an attack against someone widely accepted to have insulted the Prophet and who therefore counted as an apostate — a born Muslim who has turned his back on Islam. All extremist Islamists agree: The sentence for apostasy is death.

Just as in the original affair, when a Sunni British imam convinced the Iranian regime that this was a threat against a British Muslim population, the responses of online extremists has a nonsectarian flavor. But there is more than just a “Muslim” identity celebrating the attack on a perceived apostate: There is also the ailing Iranian imperialist element.

Iran is on its knees economically, overextended militarily and divided domestically. With this attack came the sense — to some — that the country could still flex its muscles and be felt thousands of miles away in the supposedly strongest country in the world, America.

“It highlighted the strength of the ideology,” said Ayad, “to transcend borders, transcend generations and ultimately come out with a win.”

The anti-Western motivation that Kalim so admired in the Iranian revolution is stronger than ever since the war on terror was launched. Then as now, Western culture — or “Western degeneracy” — is linked to the undermining of a “traditional” way of life and by extension the weakness of Muslim countries. Hence how the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, with the undignified scenes of coalition forces scrambling to exit the country, was greeted with joy. The attack on Rushdie was seen as similar, albeit on a smaller scale: an attack on Western degenerate values that led (via feminism, LGBT rights, cultural Marxism and so on) to assaults on Islam.

This is not to say that the attack was universally approved of in Iran. Indeed many were horrified, unable to speak publicly on what they see as an attack in their name on the fundamental human rights for which they are fighting. But it remains to be seen which strand in society will emerge stronger in the long term: the political rhetoric, transmitted in state media and across extremist forums, which validates and enables lone-wolf attacks, or the more moderate elements in society that support human rights and peaceful methods of dialogue. With the IRGC firmly on the side of the hardline regime, it’s clear that Rushdie will not be the last to suffer violence for the sake of identity building.

In retrospect, it is clear that the original events were formative for Muslim identity in Britain, with characters like Kalim Siddiqui gaining prominence and engaging with the establishment — which was unsure how to respond — in new ways.

“There was a defensive engagement with often hardline elements,” said Rashad Ali, who was a child in Sheffield at the time, “which facilitated the creation of a reactionary Muslim political identity.” New groups sprang up in the wake of the Rushdie affair, uniting Muslims at home as well as bolstering a sense of the ummah’s support stretching across the globe. Many of Ali’s generation, including him, became politically aware, served by groups that previously didn’t exist, introduced to ideas they might not have come across. “Previous ethnic identities were replaced — not entirely, but dominantly — with a British Muslim identity,” Ali explains. The Muslim Council of Britain, consulted by government and media alike for “Muslim opinions,” was a direct result. Although identity building in Iran and the U.K. was at the heart of the story over 30 years ago, all these years on, a divergence is clear. The establishment is no longer unsure where it stands and has condemned the attack as clearly as the Iranian regime’s media has celebrated it. But looking at contemporary reactions only would be to miss the fundamental changes in British society: British Muslim identity is a reality — and the fatwa over “The Satanic Verses” played a large part in its formation.