Listen to this story

In the summer of 2002, during a cultural gathering I attended for university students in Syria, a well-known actor and academic broached a touchy subject. Fayez Kazak’s talk centered on the surge of rural music infiltrating the public consciousness of the capital, Damascus, exemplified by pop singers from the regime’s heartlands in western Syria like Ali Al Deek and Wafeeq Habib, whose infectious melodies seemed to dominate every available outlet, from official television channels to the radio stations that were played in buses and cabs. The speaker hinted that politics was behind this unexpected rise. But in hindsight, the surge in such music mirrored a larger trend sweeping across the Middle East and North Africa, from Egypt and Iraq to the Gulf. The emergence of folk and rural music in urban settings was driven by a mix of factors, including the proliferation of satellite TV, technology and shifts in societal dynamics.

Back then, satellite TV was rapidly becoming a staple in Middle Eastern households, having previously been an exclusive luxury enjoyed only by the affluent few. The nightlife scene in urban and suburban areas throbbed with the beats of techno-infused songs by artists from rural backgrounds, often colloquially labeled as “shaabi,” meaning folksy or low-class, with connotations of vulgar and unsophisticated, in a society obsessed with status. (Although I tend to use “rural music” and “folk music” interchangeably, rural music is regarded with near universal disdain by elites, while broader folk music is sometimes seen as a form of cultural heritage.) In Gulf countries, drivers blasted these tunes from their car stereos. This rural music phenomenon had — and still has — its own unique flavor. It’s raw, provocative, even sexually suggestive, and distinct from the refined compositions rooted in classical forms and steeped in religious rituals performed by vocalists and reciters in the metropolises of Damascus, Aleppo, Beirut, Baghdad and Cairo.

The music’s detractors, like Syrian actors who themselves hailed from rural provinces but were, in the popular imagination, entrusted with maintaining an urban, middle-class tonality, occasionally voiced their disapproval of the genre in class terms. But despite all the criticism, the trend continued to gain momentum, particularly with the advent of social media platforms like YouTube and TikTok, its lively tunes and tongue-in-cheek, humorous lyrics perfectly tailored for the internet.

The rise of Middle Eastern rural and folk music in the late 1990s is a fascinating story of a subculture reclaiming its prominence after being marginalized and policed by cultural gatekeepers for decades. This “creeping ruralism” also tracks with significant socioeconomic shifts in rural and suburban areas, reshaping the cultural landscape in unexpected ways.

One of the figures who emerged from this scene was Omar Souleyman, a member of the prominent Arab tribe of Rabia, from a modest village near Ras al-Ayn in northeastern Syria. His trademark dark sunglasses conceal an eye condition caused by a childhood car accident, which also forced him to drop out of school after second grade. A chain-smoker, he sports a bushy but neatly trimmed mustache and wears a red-and-white “shemagh” headdress (known elsewhere as a keffiyeh), a circular black “agal” to hold the headcover and a dishdasha (a thobe or long robe).

In 2000, during the summer before I relocated from my village in eastern Syria to the capital for university studies, I attended the wedding of one of my cousins where Souleyman — before his unlikely ascent to international fame in electronic dance music — was the wedding singer. For between 3,000 and 7,000 Syrian pounds ($60 to $140 at the time), those organizing “grand” weddings would secure his services for the evening. Weddings are traditionally held on a Thursday but are sometimes celebrated over two or three days. This meant Souleyman could be fully booked for many weeks throughout the eastern region, especially in the summer months.

The preparations leading up to the celebration were a communal affair. The organizers spent the day preparing lavish lamb dishes to serve the village community, albeit predominantly those closely associated with the wedding household, including neighbors and relatives (anyone could just drop by, though). In the afternoon, the sandy courtyard outside the house was sprayed down with water to settle the fine dust, setting the stage for Souleyman and his small musical entourage to grace the evening with their melodies. Souleyman engaged the crowd with popular songs we usually listened to on cassettes, not on TV or radio. His most famous song at the time was “Jani,” the title of which was its refrain:

Jani, my gaze is drawn to the enchanting women, Jani, walking westward toward the Khabur River.

Jani, one stands tall, Jani, while the other two resemble walking birds [Graceful but not as tall,

presumably].

Jani, O you, with green eyes, Jani, the Christian maiden with blond looks.

Jani, in the name of Virgin Mary, Jani, do turn around and cast your glance my way.

“Jani” translates to “darling” in Kurdish, signaling the tune’s Kurdish origins, even though the rest of the song is in Arabic. Syrian-Arabic folk music is heavily influenced by Kurdish and Assyrian Christian cultures, groups that historically dominated parts of northeastern Syria and adjacent northern Iraq. Souleyman’s repertoire revolves around themes of love and traditions, hallmarked by tantalizing melodies, electronic beats and his distinctive high-pitched vocal style. Rooted in the Middle Eastern folk dance known as “dabka,” with a heavy Kurdish musical influence, his delivery coaxes listeners into rhythmic and entranced movement, not too dissimilar to the electronic dance music and rave scenes where he would later perform, though much more constrained and, perhaps, self-conscious.

Souleyman’s wedding performances were punctuated by his shouting out the names of those who passed cash to his crew, sometimes with an improvised verse thrown in, depending on the generosity of the sum, which ranged from 100 to 500 Syrian pounds (between $2 and $10 at the time). Such shoutouts usually involved references to tribal affiliations and well wishes to the groom, sent from notable or showy guests. (The singer would recite them between his lines, usually with the format, “Greeting, and a thousand greetings, from so-and-so to so-and-so.”) Because most of these performances would be recorded, people also hoped their names would be memorialized in recordings purchased by the public from music studios.

Tipping was how wedding singers made their money, often amounting to the equivalent of $1,000, in sprawling multiday celebrations. (I must disclose my own susceptibility to this tradition of “making it rain.” I distinctly recall engineering a shoutout that had Souleyman identify me as a student from Damascus University — information delivered to him through one of his “messengers,” who whispered instructions into his ear to guide his public praise of generous patrons — a prelude to my enrollment that, in truth, was still on the horizon. This was a nod to a culture that reveres tribal pride and heritage, and I was one of the earliest in my hometown to foray into higher education in the capital.)

Gathered around the musical crew, the attendees created a circle. Some surrendered themselves to dance, others clapped along, while the majority observed with a quiet intensity. Among them, a pair of village-renowned dabka dancers stood out, capturing the spotlight with their practiced routines. In our conservative, close-knit society, an exuberant display of dance was perceived as improper. So most individuals swayed with a composed and collected style, resisting any impulse toward uninhibited buoyancy. I remember that one of the dabka dancers, a sojourner on brief leave from his military service in Hasaka in the north east, introduced a certain twist to his dabka that was deemed too “effeminate” by old-fashioned bystanders, a cultural perversion imported from outside. I wouldn’t be surprised if they still used it against him to this day.

This was the world of humble singers like Souleyman. Back then, it was my understanding of the reach of his music. I was wrong. I learned about his stunning global rise during my postgraduate studies in Nottingham, in the U.K., in 2008. The arrival of YouTube opened a portal to nostalgia. I sifted through videos of the singers who had been the soundtrack of my formative years — predominantly Furati (Euphrates) music, from the eponymous river basin in Syria and Iraq. Imagine my astonishment when I stumbled upon clips of Souleyman performing in venues in Europe and North America, in the same traditional Arab attire. This was a far cry from the intimate wedding setting of that summer of 2000, the difference magnified by the scale of the crowd and the energy coursing through it. The frenetic beats of Souleyman’s performance electrified this global audience, most of whom were unlikely to understand the lyrical nuances of his music. The women he sang of, including the titular figures of his famed “Jani” song, transcended their roles as lyrical subjects. They now aspired not just to cast their glance his way but to claim front-row positions, fervently dancing to his rhythms.

Souleyman’s energy and intensity had broken free not only from the local townships and neighborhoods of rural Syria but also of the entire Middle East. Up until then, such global reach was the exclusive right of contemporary giants like Egypt’s Amr Diab and Iraq’s Kazim al-Saher, but even they performed mostly for Arab communities in the diaspora.

My nostalgia only deepened. I took pride in the fact that a fellow Jazrawi — hailing from the region of Jazira, or eastern Syria — who was now an international sensation had once upon a time performed in my own village. I delved further, wondering whether others had shared Souleyman’s trajectory. But it seemed that the global stage was not an easy conquest for many. Other voices I had admired managed to carve out their own significant niche within the region, but hardly anyone had embarked on the journey that led Souleyman to his international acclaim.

The situation changed with the rise of social media platforms, coupled with the surge of refugee and diaspora communities in Europe in the aftermath of the tumultuous uprisings of 2011. Rural and marginalized areas, often the most ravaged by violence, produced a sizable portion of refugees within the region and throughout the West. In their exile, they were naturally drawn to music that reminded them of home, much as I was when in Nottingham.

The story goes back to before the wedding where I heard Souleyman sing. His is a tale of success that relied on both organic networks and emerging technologies, amplified by the rise of social media. This music from the peripheries — both geographical and cultural — not only broke out into the mainstream but also took Arabic music global.

Up until the 1980s and early 1990s, musical performance in rural areas in countries like Syria, Iraq and Jordan was generally a solo act. The person singing was typically the fiddler too, and the instruments were traditionally limited to the “mutbag” (a flute-like instrument, also known as “mizmar,” “mijwiz” or “ney” in the region) and the “rebaba” (a precursor to the guitar, featuring one string, recognized in various cultures as the “rebab”). Traditionally, these musicians, skilled in either of these instruments, would often perform at weddings or social gatherings organized to celebrate a reconciliation between two clans or to honor guests in the abodes of tribal chieftains. For the most part, these artists earned their livelihood by journeying from one region to another, entertaining at significant Bedouin or rural residences, often composing poetic verses as an ode to the tribe or clan they visited — a time-honored tradition steeped in centuries-old heritage.

This legacy persisted through the modern age, sometimes enhanced with the addition of a drummer and dabka dancers. Then arrived the electronic keyboard, which made its mark in the Middle East in the mid- 1990s. A transformative force, the keyboard catalyzed the rise of techno-folk songs. Armed with robust loudspeakers and an all-encompassing instrument capable of generating drumming, flute-like sounds and ululating, gifted wedding singers ascended to regional celebrity status within a short time.

The Syrian academic and poet Mohamed El Yasary was an instrumental figure in the rise of this phenomenon in both Syria and Iraq, having composed approximately 500 songs from 1996 to 2004, many of which were performed by celebrated Syrian and Iraqi folk singers. El Yasary attributed the rise of folk songs to a blend of cultural diversity and richness, an observation that may appear unconventional to those who criticize this genre for profanity and lowbrow elements.

The eclectic styles of folk singers draw extensively from a rich fusion of classical Arabic, Kurdish and Mardali traditions — as well as Bedouin forms in the Arabian Peninsula and elsewhere. (Mardali is an Arabic dialect originating from the Turkish city of Mardin, spanning from southern Turkey to eastern Syria,and extending to Mosul and Anbar in Iraq.) This blend bears traces of Kurdish, ancient Aramaic and Assyrian languages and cultures. Because of restrictions imposed by the Assad regime on Kurdish language usage in public spaces, some Kurdish singers performed in Arabic and Kurdish producers helped produce for the likes of Souleyman (his biggest online hit, with 120 million views on the original YouTube video, is a Kurdish tune called “Warni,” which means “Come to Me”).

In this sense, the resurgence of folk music represents a genuine cultural revolution for these ancient cultures, with folk singers like Souleyman embodying this transformative shift. Despite suspicions of political facilitation, this cultural rejuvenation extends to artists from the regime’s core regions.

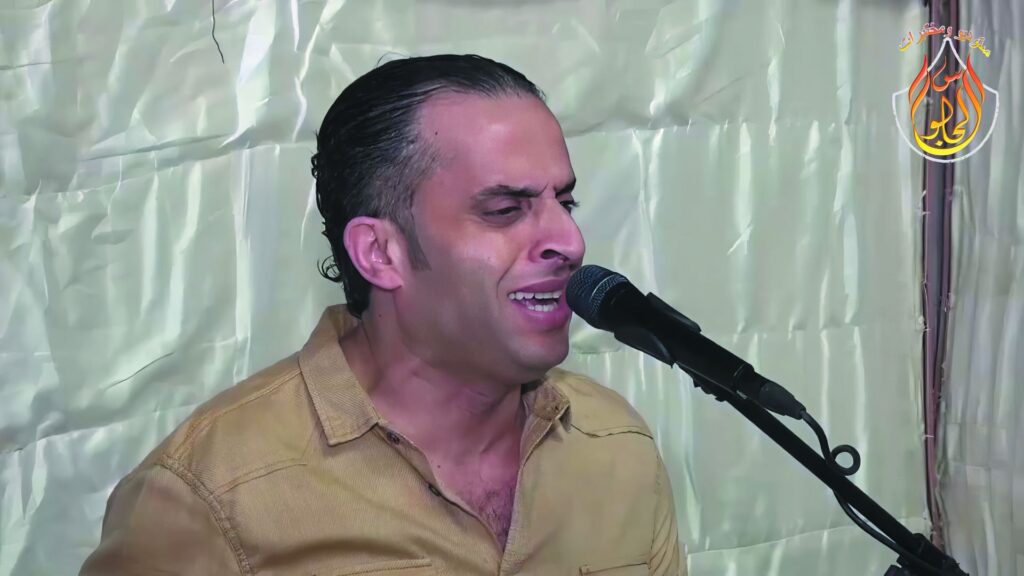

Among the rising stars who followed in Souleyman’s wake was Saria al-Sawas, from Talkalakh in western Syria. Starting her career in local parties and clubs in Syria, she initially embraced the style of fellow coastal region folk singers — from the Alawite heartlands referenced by the Syrian actor Kazak. In recent years, al-Sawas has performed in numerous cities, including Dubai, Hamburg and London.

These folk artists from the coastal region garnered more exposure through mainstream television and radio broadcasts, a phenomenon often attributed to influential patrons from the pro-Assad heartlands, if not the government itself, as Kazak insinuated in 2002. That said, folk music from the Alawite areas has also encountered historical limitations, even during the rule of the Assad family.

Al-Sawas’ journey, though not devoid of controversy, has been influential. Her songs, peppered with explicit sexual references (“Place your lips on mine, and let hell break loose”) and performed in nightclubs, drew both acclaim and censure. As a woman artist she faced a more intense spotlight, a reality that not only resulted in criticism but also ignited a fresh wave of singers, including in Iraq. Al-Sawas’ musical journey can be seen as an extension of the Euphrates music tradition from eastern Syria. She transitioned from singing in the style associated with the heartlands of the Assad regime to embracing the musical identity of eastern Syria. This shift was largely influenced by the soaring popularity of Euphrates music, catalyzed by Souleyman’s breakout hit “Khattaba” in 2004. (This song was the first and only of his works to be popularized nationally by Syrian television, which he said also caught the attention of an American record company, leading to his inaugural tours in Europe in 2008 and later in the U.S.) This musical evolution helped al-Sawas amass a dedicated following in both Syria and Iraq.

In Iraq, songs of the same style sprang to regional fame almost simultaneously with the U.S. invasion in 2003. The first hit was “Yal Burtuqala” (“O You, the Orange”) by Alaa Saad, the fruit being an allegory for a lover, “dangling in the distance and glowing, tormenting him.” The song’s success sparked a series of similar tunes, each evoking different fruits and pantry items. Commenting on its popularity in 2004, Saad said people in the region had been thirsting for Iraqi music.

However, even with songs like “Yal Burtuqala” gaining popularity, the ascent of Iraqi music across the region was a gradual process that spanned several years. It entailed a slow journey for Iraqis to reestablish their cultural identity within the broader neighborhood, following decades of isolation, triggered by events such as the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, the subsequent invasion of Kuwait, U.S. sanctions during the 1990s and the 2003 U.S. invasion. This meant that the rich and diverse music of Iraq was popular within small circles outside the country, such as in eastern Syria (Iraqi music remains among the most underrated and undiscovered gems within the broader region, because of this isolation). The isolation affected how Iraqis viewed their culture and dialect in the region.

This self-perception changed with time. The rise of social media helped Iraqis to assert their dialect and customs in the regional public space and find a market in the Gulf Arab states, which are now the region’s most important musical and media hubs. The gradual success of Iraqi songs was in part enabled by the migration to the Gulf of wealthy Iraqis, who would engage famous singers to perform at parties and weddings. They had often risen to fame by producing low-budget yet viral songs, infused with street lingo and folkloric cadences. Thus these social media stars began to gain attention in the critical and competitive Gulf market, through a newer techno-infused form based on “housa” (an ancient tribal or rural form of chants heard during celebrations or wars).

A salient example of this trend is a 2018 hit, “Taal.” Garnering an astonishing 800 million views on its original YouTube video, this song, performed by three young Iraqi men in what appears to be a locker room, hinges on electronic keyboards and a techno-infused vocal edit. The song’s relentless rise launched a career for the trio, who claimed to have produced some 700 songs in an interview with the Saudi channel MBC in 2020. The lyrics, stripped to their essence, articulate a simple yet compelling sentiment: “Come, I will indulge you, until you’re satiated with affection and love. Come, decent soul. My gaze is for no one but you, so come.”

Between “Yal Burtuqala” in the early 2000s and the techno-infused housa today, Iraqi street singers gained immense popularity on YouTube in the mid-2000s, often using no instruments at all. Aidan Abu Hamra and Juma Attag are prime examples of this trend. Abu Hamra has a cultish following on social media, with more than 700,000 YouTube subscribers. He does not sing with instruments or on a stage. His videos are mostly of him hanging out with his friends in the streets, improvising lines while his friends beat an empty barrel. One video shows him sitting on a sidewalk, singing about his long day of doing manual labor. His singing is punctuated by his swatting a persistent fly with his hands, and the words he sings seem to come from the heart, reflecting his state of exhaustion and desperation: “Exhausted, working hard and my situation is miserable, this labor work has depleted me. I have sleepless nights.” The video has roughly 7 million views.

Attag enjoys similar popularity, creating his music by beating his hands on a table. In one song, produced in many videos, each watched by millions, he changes the words of a famous Iraqi song titled “Umm Shama” (“The Woman With a Beauty Spot”) to critique daily life: “I get intoxicated, I take pills, and I am an unrepentant troublemaker. Uncle, the barman, pour me some snacks, for I’m drunk and agitated. This country is useless; this country is pointless.”

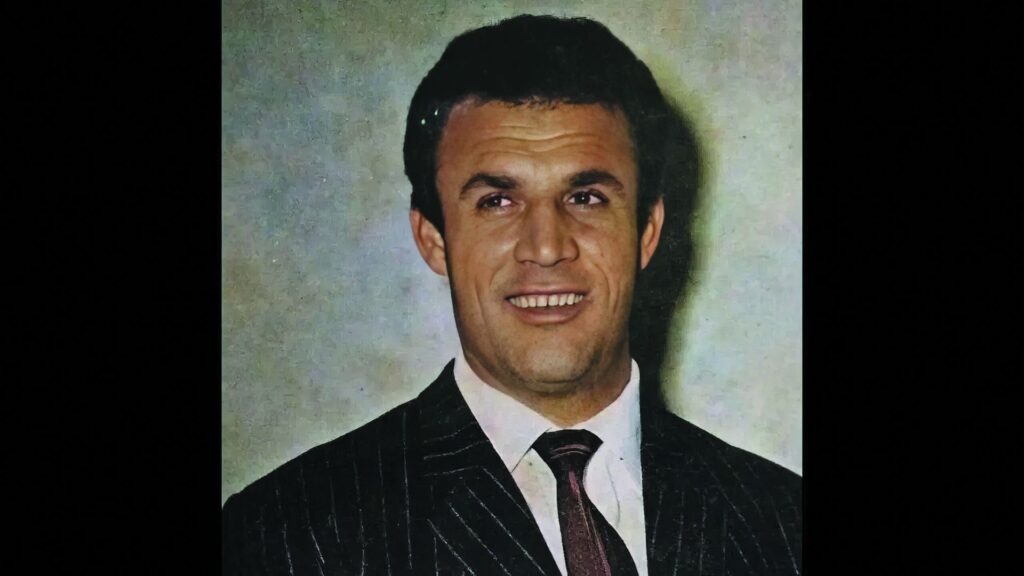

Shaaban Abdel Rahim epitomized the same trend in Egypt with his idiosyncratic tunes and contentious lyrics. He was born Qassim Abdel Rahim Hassan in Ezbet Bilal, a slum, in the district of El Sharabiya at the northern edge of Cairo. His family are so-called Saidis, from Sohag in Upper Egypt. (While “Saidi” literally refers to people from the south of Egypt, it generally carries connotations of a rural and traditional lifestyle. Saidis tend to be the butt of jokes in Egypt, and stories poke fun at their adherence to rural norms and traditions.)

Like Souleyman, Abdel Rahim’s eccentricities reflect his humble beginnings. With a rugged look, a penchant for donning mismatched attire and adorned with multiple gold necklaces and watches, he cut his teeth working in his father’s laundromat and performing at local weddings from the age of 15. Recounting his early days to Dream Art, an Egyptian television channel, he said, “We’d sing until either a police officer comes in to end the wedding or a thug comes in to ruin it.”

Abdel Rahim died in December 2019 at the age of 62. He rose to regional fame in 2000, propelled by two smash hits — one chronicling the all-too-familiar personal resolve to give up smoking and another (perhaps an equally familiar sentiment in the Arab world) lambasting Israel. These songs encapsulated the genre’s essence: The lyrics are disarmingly simple, mirroring his casual, humorous conversational style, an approach that is more relatable to ordinary folk than the often-complex compositions of renowned poets, whose verses are used in classical and some modern Arabic music.

His melodies, too, were uncomplicated, marked by a recurring vocalization of an elongated “ay,” infusing a musicality into otherwise plain words:

I will give up smoking, and become a new person

Starting from January, I will be lifting weights

I will crack melon seeds, and drink light tea

I will go down to the store, and buy a new shirt

Ayyyyy, and buy a clean shirt.

He is better known for his first regional hit, titled “Ana Bakrah Israel” (“I Hate Israel”), which features lyrics like: “I hate Israel, and I like Amr Moussa, with his studied words.” Moussa, then Egypt’s foreign minister, met Abdel Rahim and reportedly informed him that the song had become a sensation in diplomatic circles worldwide. After that, Abdel Rahim had a habit of chiming in on significant global events, effectively serving as a litmus test for the prevailing political currents in the region. He condemned the self-styled caliph of the Islamic State group in 2014, hinting that his caliphate was a foreign conspiracy (“O Abu Bakr, O Baghdadi, the Amir of Criminals, you come across as dumb and phony, guiding a bunch of crazies. Caliphate, what caliphate are you talking about? More like a fantasy. Who sent you? Do tell.”) and even critiqued Donald Trump when he was president (“Trump, it’s clear he’s lost his bearings. He should be securely confined, and everyone should be careful, he might bite or kick”).

Abdel Rahim’s ascendancy and popularity, however, brought about a chorus of criticism from various quarters in Egypt, who accused his work of corroding cultural norms. One of his detractors was Hany Shaker, a prominent Egyptian singer and actor, who in 2020 claimed Abdel Rahim’s music was a greater danger and worse virus than COVID-19. In his role as head of Egypt’s Musicians’ Syndicate, Shaker waged a campaign against what he dubbed “mahraganat” music — literally concerts, used pejoratively to refer to riffraff off the street — a term referring to techno-folk music born in impoverished urban or rural areas that spread through social media.

The next generation of folk singers, spurred on by the rise of Abdel Rahim, inherited his legacy, though their lyrics took a raunchier turn. This shift was evident in Egyptian artists like Hamo Bika and Omar Kamal, who became associated with “baltaga” (thuggery), substance abuse and alcohol. Their contentious relationship with the Musicians’ Syndicate saw Bika resorting to threats of violence to secure performance permits. While their music was cheap in production value — and profane and unrefined — it was anything but uninteresting, and attracted a sizable social media following. Consider, for instance, their 2020 work capturing the COVID-19 zeitgeist, peppered with irreverence toward individuals in China: “The Lord has spared us from this, because we’re very pure from the inside. For us, it is all finished, because we are backed by an army and a president protecting us.” Their songs often include references that are friendly — even pandering — to the Abdel Fattah el-Sisi regime, probably as a way to protect themselves, as street singers usually operate without licenses.

In April 2022, the duo faced “morality” charges, on the grounds that their brand of art clashed with “Egyptian values and norms.” This legal action was only the latest episode in a string of controversies, including a prison sentence in 2020 stemming from a video posted on social media depicting the pair singing and dancing alongside the Brazilian performer Maria Lurdiana Alves Tejas, a social media personality with a substantial following on platforms like Instagram and TikTok. It is not clear why that wouldwarrant a prison sentence, but the duo had been entangled in squabbles with other artists and were under attack generally for their music and lyrics, including with fellow folk singers like Abdel Rahim’s son, Issam.

Though Egypt’s authorities have attempted to rein in the spread of mahraganat music, the phenomenon has proven difficult to contain in the age of social media and with the prevalence of low-budget productions.

In Jordan and the Gulf region, folk music has seen similar trends, but with different dynamics than those observed in Syria, Iraq and Egypt. In the latter set of countries, the folk nature of the art was diluted by techno music and at times suggestive lyrical content. Artists in Jordan and the Gulf preserved the conservative nature of Bedouin music, which in its throaty and ceremonial style resembles the haka traditions found in Hawaii and New Zealand. The same trend has unfolded within Bedouin communities in Israel’s Negev region and Egypt’s Sinai, where the style has also gained viral popularity in recent years.

This Bedouin form predates Islam in ancient Arabia and goes by various names such as “Dihha” (or “dihhiya”) in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq (where it is also called “housa”) and the Levant; “nidba” in Oman and the United Arab Emirates; “laab” in Yemen and Saudi Arabia (interchangeably or together with dihha in the latter). It is mostly associated with tribes or regions spanning from the Arabian Peninsula to Bedouin communities in Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Israel and Egypt. The dihha, for example, is claimed by the tribe of Enaza as their creation, either originating or being demonstrated in the iconic pre-Islamic battle of Dhi Qar between Arab tribes and the Sassanid Empire in the seventh century, when Arab tribes mimicked the roars of lions and the camel’s dromedary vocalizations to intimidate the Persian army. Historians do credit the tribe with leading and winning the battle of Dhi Qar in southern Iraq.

Jordanian singers Sharhabeel al-Tamari and Ahmad al-Shaykh have injected techno elements into their performances, but they have popularized the Bedouin art while maintaining its raw and reserved character. Another notable figure, Moen al-Asam, a Bedouin singer hailing from the Negev region, gained popularity for introducing techno-infused Dihha music in Israel/Palestine. (His work took a controversial turn when one of his compositions caught the scrutiny of Israeli authorities due to its alleged praise of Islamic Jihad.) The revival of the dihha in Sinai — which has for years been associated with jihadist violence, including against locals who engaged in music or religious practices condemned by the radicals — seems to reflect the area’s improved security. These expressions appeal to a more niche audience compared to the widespread appeal of artists like Souleyman, but the genre has in recent years transcended its traditional boundaries and become a fixture in large parties and even in political battles.

The resurgence of this form has also galvanized communities across the region into reclaiming these chants as part of their heritage and identity (as the Eneza tribe does with the cross-regional dihha dance), giving rise to subnational and transnational identities or divisions along tribal and regional lines.

Alongside their positive aspects of diversity and richness, folk songs have also earned attention due to their suggestive, colloquial or profane language, wielding familiar and tantalizing themes.

Obscenity in these songs is a cultural paradox: Rural societies are known for their social conservatism and taboos, yet they have produced music that openly discusses women and sex. Take a traditional song presented within the context of the Kurdish documentary “Daren Bitene” (“The Lonely Trees”) about music in northeastern Syria, directed by Shero Hindi in 2017. The scene portrays two male vocalists clad in traditional Arab garb, alternating their voices. The appearance and demeanor of Rakan Fehran and Yasin al-Abud seamlessly conjure a sense of community and conservative values reminiscent of a village such as my own. However, it’s the lyrics that present a paradox. Their flirtatious expressions, cleverly interwoven into the verses, seem as though they’re an organic part of everyday language, devoid of any innuendo.

One of the singers croons, “My heart is irresistibly drawn to alluring women, yearning for moments of joy. You, adorned with the head covering, have woven an enchanting charm around me.” Following this, the other vocalist adds his voice: “To me, she who passed by, the one whose breasts resemble two stars in a midnight sky, she has unconsciously entrapped me. … With graceful steps, she approached, her bosom reminiscent of a delicate eggshell.”

These expressions are common, but they are rarely even noticed or called out by conservative listeners. Exceptions exist: I recall a particular uproar during my youth, when rumors circulated about a singer facing a backlash from fellow tribe members, leading a rival artist to compose a song admonishing him for flouting traditional norms. The song in question, “Warda,” tells the story of a man’s tryst with a woman named Warda from his village. This 1998 song was eastern Syria’s first national hit. According to recording studios in Aleppo, the song competed neck and neck with an album by the renowned (and respectably middle-class) Lebanese singer Najwa Karam, titled “Ya Hilo” (produced in 1996).

Beyond its explicit themes, the song offers a vivid description of life in rural areas and the rendezvous of lovers. The lyrics start with the singer’s entreaty to Warda to meet him in the cotton fields, specifically in the northern plot. Warda conveys her inability to meet the next day, owing to her obligation to pick cotton for her mother’s family (cotton picking is a collective endeavor in my part of the world; we call it “fazaa” or social volunteering). She suggests Friday as a suitable occasion to rendezvous at the edge of one of the fields. The singer continues:

Warda showed up, and what a beautiful sight it was! She had a lot of red lipstick, and her hair

bangs were neatly straightened

I extended my hands to pull her head cover and touch her. She said, rip off the buttons of my dress

I said, I love you, and love is not a sin

She said, love me, Hussain, a romantic love;

Kiss me in a refined manner;

Cuddle me in your lap, and let me sleep with affection;

But wake me up when the workers come

The song continues the narrative. Circumstances take a turn for the worse when cotton pickers chance upon the clandestine pair. Warda leaps off his lap, seething with anger. Her brother, consumed by rage, confronts Hussain, who passionately declares his love. In response, her brother says he would rather die to protect the family’s honor, brandishing a Soviet-era rifle and firing in Hussain’s direction, but missing him. Chaos ensues, witnessed by onlooking workers in the vicinity. A scandal of such magnitude could easily plunge two clans into a relentless cycle of intergenerational retribution.

The tale offers a glimpse into the intricate layers of rural societies, where seemingly contradictory elements coexist — social conservatism alongside unabashed lyrical explorations of human relationships and sexual desire. In this dynamic, the folk songs serve not only as an artistic outlet but also as a reflection of the complex interplay between tradition and artistic innovation, between reverence for heritage and the audacity to push boundaries.

As these rustic musical traditions continue to evolve and adapt, they navigate a fine line between cultural preservation and modern expression. The lyrical voices that emerge from these landscapes serve as both time capsules of age-old sentiments and the living echoes of societies in transition. Their verses, often simple in their eloquence, encapsulate the essence of ordinary human experience — the yearning, the celebration, the heartache and the resilience.

It is this dimension of folk music — the rustic nature characterized by sexual innuendos and raw expressions — that attracts the ire of cultural purists. But this is also the source of its power and, indeed, how it has persisted and grown organically, despite decades of efforts to either ignore or erase it. Even seemingly inconspicuous figures like bus and cab drivers and venues like nightclubs and weddings played a significant role in proselytizing for rural music.

In Syria, the association between this genre and cab drivers was so pronounced that it earned the moniker “garage music.” I was in high school when the song “Warda” came out and took the country by storm. Because my village had only one elementary and one middle school at the time, I commuted to the high school in the city center nearby. Minibus drivers would curate their cassettes based on the passengers on board. If older individuals were present, the radio emitted traditional melodies hailing from the Euphrates culture. If it was mostly students or young men like me, drivers would blast out songs like “Warda” before stepping on the gas and heading to or from the city. The music thus found its way into everyday settings, gently sidestepping potential clashes with the sensibilities of the older generation.

In Egypt, “tuk-tuk” cars (Egypt’s version of India’s rickshaws) became conduits for street music long before the rise of TikTok. As the drivers hailed from less privileged backgrounds, they favored songs characterized by vibrant rhythms and straightforward lyrics that resonate with them. Toiling amid the bustling urban landscapes, these drivers seek solace in the magnetic pull of such melodies. For example, Abdel Rahim sang about the problem his neighbors face daily with power cuts: “Electricity keeps on having interruptions, and the heat is getting extremely intense. It goes off for 20 hours, and then returns for only four hours.”

Nightclubs also became unexpected platforms for amplifying rural songs. The frenetic tempo of these tunes, coupled with the unfiltered atmosphere of clubs, resonated deeply with tourists from the region. In an environment where conventional boundaries were more fluid, the profanity often associated with these songs was accentuated. Such a setting was conducive to explicit language, intoxicants and lewd references, provoking vehement criticism from cultural traditionalists.

One of the songs that faced heated censure for its lyrics was one popularized by al-Sawas, that referred to sucking on a lover’s lips. The line was taken as sexually suggestive, especially because of the choice of words (“bousa” for kiss would be less graphic than “massa,” which also implies a more involved act). Ali al-Iraqi, a folk singer from Iraq, had to change the words to avoid potential backlash, saying he would be more explicit if he were in Syria. Instead, he added a religious reference, apparently to distance himself from the meaning, singing about kissing “like an infidel would.”

Weddings also emerged as crucial vectors for the dissemination of these songs and their suggestive lyrics, albeit for different reasons. Even within the conservative fabric of rural societies, weddings provided a space for lyrical innuendos, often veiled in metaphors and cultural allusions to circumvent the transgression of societal norms. Growing up in a deeply conservative society, such references were common for me to hear in jokes and wedding songs, albeit mostly limited to such contexts. These musical expressions often served as conduits for subtle yet direct references to sexuality and desire, encapsulated in lyrics that both reflected and challenged societal expectations. “Do not surrender your breasts to naughty boys,” as Souleyman sings in “Jani.”

This phenomenon isn’t unique to the region; it echoes through history in various cultures like the bawdy ballads of England or the erotic traditional music found in rural India. A notable example from pop culture is the Italian song performed in the opening scene of the film “The Godfather” by an old man and Carmela, Vito Corleone’s wife and the mother of the bride. The two sing in Italian but make gestures that suggest the sexual meaning of the metaphors, taken from “Che La Luna” — a traditional Sicilian coming-of-age song, in which a mother and daughter speak about potential suitors, lightheartedly using tools of the trade as sexual references:

If you marry the baker boy

He will come and he will go

He will always mix the flour in the pan

If you marry the baker boy

He’ll have a cannoli in his hand.

…

If you marry the musician

He will come and he will go

He will always be playing in the band

If you marry the musician

He’ll have the trumpet in his hand.

Accusations of profanity obscure the tendency of these songs to reflect daily life and raise issues affecting ordinary people in much of the Middle East. Such attacks are also often driven by class dynamics, which frame these songs as symbolizing rural and unrefined ways. These songs often break social, political and religious taboos more than mainstream music does, because, as one Jordanian study put it, folk music is not as closely monitored as other genres are. It is also worth noting that even mainstream singers have produced songs that are equally explicit, yet the response to folk music’s content has been particularly vehement.

Also, instances of profanity and vulgarity are not the genre’s defining characteristics. What resonates most powerfully within folk music is its connection with rural areas, suburban enclaves and marginalized neighborhoods — it is a sonic embodiment of the everyday language and lived experiences of ordinary people. These artists have also deftly navigated culturally sensitive topics like arranged marriages and kinship bonds, while proudly championing other traditional values and norms. In one song, a woman complains about forced marriage: “I don’t want to marry my cousin. Don’t force me, father. My heart loves a stranger. I do not want any one of my relatives,” before Souleyman adds, “She thinks of you as a brother; she was a baby who grew up with you. She follows her heart, and her heart is not taking a liking to you.”

The surge of folk or street music has ignited a passionate backlash in different areas over the years. Detractors point to sexually explicit content and perceived artistic deficiency. In Syria and Iraq, numerous actors and singers have railed against the genre. In Egypt, authorities have gone so far as to take legal measures to curb the rise of these musicians, exemplified by the recent denial of a visa for Souleyman’s performance in the country. In May, Iraqi musicians, folk poets and songwriters held a conference in Basra to sound the alarm on the “cultural deterioration” caused by what they described as artistic decline and crass lyrics, calling on authorities to clamp down on such music. In Lebanon, discussions on TV have criticized the influx of Syrian folk music, deriding it as “trash” and “low-class.” Some commentators have gone so far as to argue that this musical form has no place in the esteemed tapestry of Lebanese culture, an astonishing remark from the place that produced risque and controversial songs by the likes of Haifa Wehbe and Nancy Ajram.

These reactions not only underscore the sweeping influence of folk music throughout the region but also point to a more profound issue of cultural curation and policing exercised by urban elites over the past century. Often driven by nationalist ideologies, this top-down approach has exalted particular musical forms while stifling others. Even when folk music is sanctioned for broadcast on national platforms, it is often presented in a sterilized fashion, as a cultural relic to be ceremoniously feted on select occasions, rather than an authentic and vibrant art that resonates within local communities.

Exceptions to this overarching trend certainly exist. In Syria, Fahd Ballan from Sweida (1957-1997) and Dhiab Mashhour from Deir ez-Zor (1964-2022) left indelible marks on Syria’s drama and music scenes despite their infrequent appearances on television. Their legacy emphasized the distinct musical styles originating from the southern Houran and eastern Euphrates regions of the country, which share cultural heritage with Jordan and Iraq, respectively. Artists from Upper Egypt have also made sporadic appearances over the past century. Jordan is a further exception in that the government actually encouraged indigenous folk music and promoted it as part of the state’s identity and to counteract Palestinian-Jordanian artists like Diana Karazon.

However, modern technology and socioeconomic dynamics have steadily dismantled the historical marginalization of this genre over the past two decades.

The proliferation of satellite channels in the early 2000s, followed by the surge of YouTube and other social media platforms, dealt a blow to the dominance of traditional programming on official television and radio stations. A seismic shift was set in motion, changing the measure of success from the exclusive purview of urban elites to the wider spectrum of popular appeal. This recalibration ushered in a newfound acceptance of the “low” or esoteric artistry from rural enclaves.

The tale of Middle Eastern folk music’s meteoric rise over the course of a mere decade or two constitutes a remarkable achievement, against considerable odds. Critics may harp on specific viral tracks to make their case, yet folk music merits a broader perspective — as a continuation of a centuries-old musical heritage now liberated from the stranglehold of geography and from the self-appointed arbiters of culture.

This article was published in the Fall 2023 issue of New Lines‘ print edition.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.