On the night of Oct. 7, hours after Hamas militants drove gun-mounted pickups through gaps in Israel’s border fence to commit the most prolific act of violence against Jews in a single day since the Holocaust, protests in support of Palestinian liberation formed in the streets of Europe. I saw one of them in Berlin — a honking, chanting crowd on a corner of Sonnenallee in the Neukoelln district, attended by helmeted German cops.

Neukoelln is lively and diverse, with a Muslim population shifting in balance from Turkish to Arab. Sonnenallee in particular is known for its Middle Eastern bakeries and hummus restaurants. I’m comfortable in Neukoelln, but the earliness of the protest felt sinister, because opportunities to rage against an Israeli war would be rich in the coming weeks — did they have to be on the street now, just after a historic massacre by Hamas, before Israel had even responded?

Apparently yes: Cheering the massacre was the point of the demonstration, which had been arranged by a Palestinian group called Samidoun. Because of its role as a funding channel for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine — and perhaps because Samidoun’s Instagram page posted a photo of activists handing out baked goods along Sonnenallee that afternoon, with the caption, “Distributing sweets on ‘Arab Street’ in Berlin, celebrating the victory of the resistance” — German Chancellor Olaf Scholz moved to ban Samidoun, and its protests, as a threat to the German constitution.

Middle Eastern politics have never been easy for Berlin. The German state supports the Israeli one, for obvious reasons, and the narrower limits on free speech here (compared with the U.S. or the U.K.) are an outgrowth of the Second World War: You can’t praise Hitler, fly a swastika, deny the Holocaust or utter antisemitic hate speech. Cases of neo-Nazism are investigated by the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, which also pursues terrorist groups and their funders as threats to Germany’s postwar democratic order. Under these terms, it was right for Scholz’s government to shut down Samidoun.

But the tendency in Berlin right now is to squelch as much criticism of Israel as possible. German demographics have changed because of mass migration from the Middle East, which reached a high point in 2016, and not all Muslim newcomers understand Germany’s past. Image-conscious politicians are keen to avoid headlines about antisemitism. But 10 days after the Hamas massacre, sure enough, an unknown person tossed a pair of Molotov cocktails at a Jewish community center in central Berlin. The building wasn’t damaged, and no one was hurt, but the story raised the usual ghosts.

“It’s a pure rage, and a desire to be part of a big movement against the Jews,” said a Berliner named Shlomo Afanasev to Deutsche Welle TV, standing outside the community center. “And that’s what scares me.”

It’s objectively frightening. But the new German zeal to shut down antisemitism has a brief history of its own.

In 2018, an exhibit at the Jewish Museum of Berlin on the history of Jerusalem inspired a critical open letter from Israel, which first came to public attention in a newspaper called “Die Tageszeitung,” which is aligned with the historically pacifist Green Party. The unsigned letter argued that the Jerusalem exhibit “reflected mainly the Muslim-Palestinian narrative.” Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s office had reportedly sent a copy straight to Chancellor Angela Merkel’s office earlier in the year.

The letter’s focus was the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign, which aims to end Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories through international business pressure. It criticized a number of outfits in Germany, all well respected, with some federal support, though most had a broader focus than Israel — including the Jewish Museum; the Heinrich Boell Foundation, a political NGO associated with the Green Party; Catholic Relief Services; and the Berlinale, Berlin’s beloved film festival.

The letter appeared just after a domestic “Loyalty in Culture” initiative in the Israeli Knesset, supported by Netanyahu, which would have pulled public funding from Israeli arts groups that “harm or dishonor” symbols of the state. This bill stalled, but in 2019 the German Bundestag declared BDS “antisemitic.” The governing parties staked this position through a nonbinding resolution — a way to make a ringing statement in the Bundestag without passing a law.

Again: Germany has to be careful. The BDS proposal to boycott Israeli corporations carries an echo here of Hitler’s boycott of Jewish businesses. The Bundestag declared the movement antisemitic because it “branded all Israeli citizens of Jewish faith” as oppressors. Therefore, government officials try not to support (but can legally ignore) any artist or speaker who supports BDS. Therefore, absurdly, in late 2019, an Israeli-born klezmer singer named Nirit Sommerfeld — daughter of a Holocaust survivor, granddaughter of a man murdered in Sachsenhausen — had to be warned about voicing support for BDS from the stage by some nanny-minded Munich officials, who also visited her show to inspect the content. Sommerfeld answered with an outraged blog post, announcing that BDS was not her defining topic, and, anyway, she would not be scolded about antisemitism by the descendants of antisemites.

A German city government, in effect, surveilled a klezmer show by the daughter of a Holocaust survivor to ensure political correctness, which is not a very democratic thing to do. But it has happened to dozens of public figures. The British musician Brian Eno, the Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe and, most recently, the Palestinian author Adania Shibli have all been dinged by the German zeal against antisemitism. A prestigious award ceremony for Shibli was canceled at the Frankfurt Book Fair a week ago because of the Hamas massacre in Israel. Her new novel, “Minor Detail” — praised by such high-profile writers as J. M. Coetzee — contains a scene featuring an Israeli militant in 1949 who rapes a Palestinian. This was deemed too much for a book fair audience after Oct. 7. Her ceremony was canceled. Litprom, which hands out the award, insisted to a website called The Conversation that the award was still hers, however: “We thought it right to hold the award ceremony at a different time in a less politically charged atmosphere.”

It should be clear that this is no way to run an open society. German reaction to Middle Eastern politics tends to split into rigid categories — the right voicing support for Israel, the left marching for Palestinians — which do not quite reflect Middle Eastern reality. Debates about the Holocaust are also a tangle of profound historical guilt and desperate wishes for redemption. In this basic sense, the hypersensitivity, and thoughtless condemnation, of these German culture wars mirror “woke” flame wars and cancel-culture zealotry in the U.S.: People with no direct responsibility for the historical sins in question feel they know just how to handle the problem, and the solutions generally involve silencing someone else.

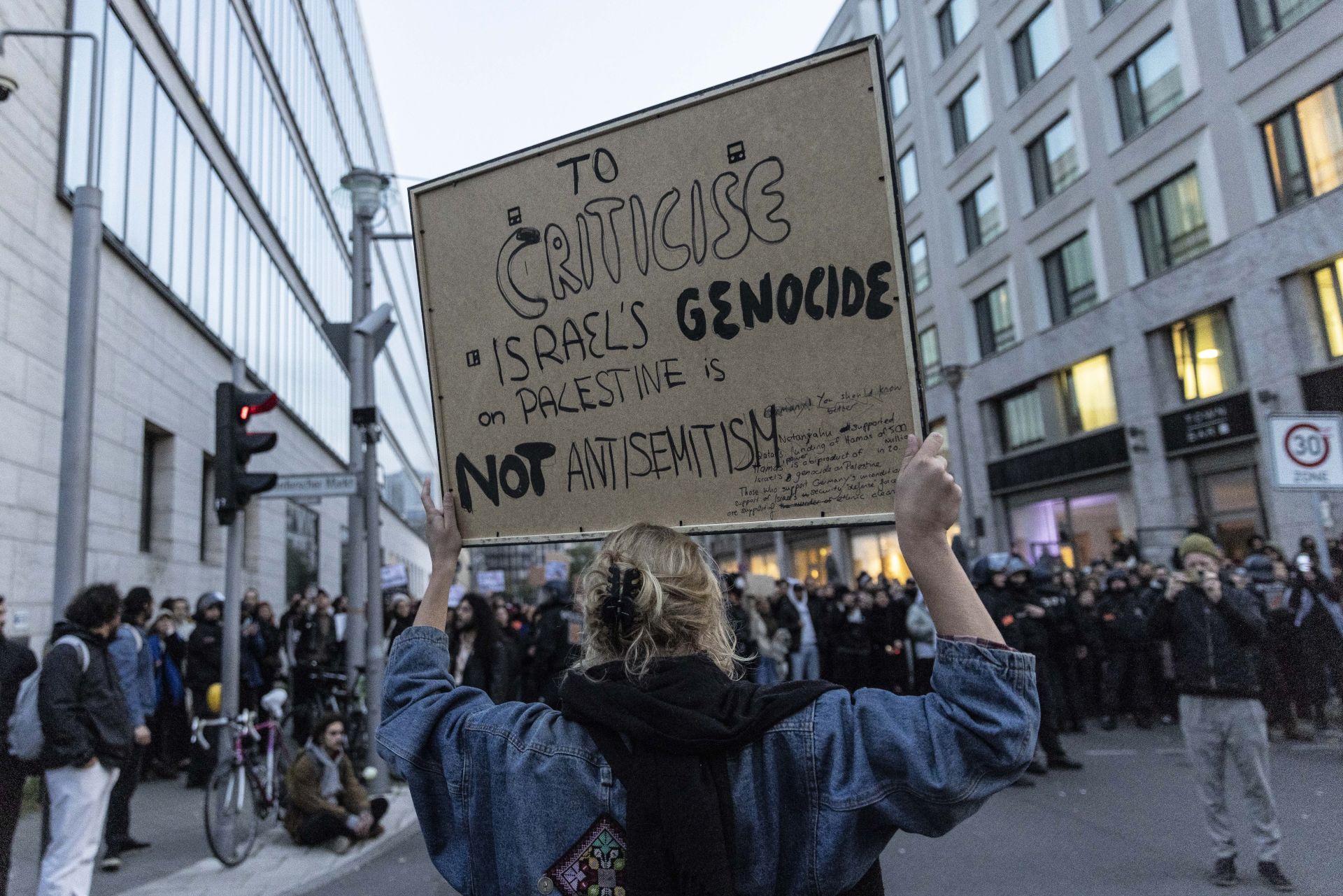

In the weeks since Oct. 7, Israel has prepared a ground invasion and conducted an air campaign over Gaza. The Berlin groups warning against collective punishment have broadened into a more sophisticated coalition of critics, including liberal Jewish and left-wing groups like “Youth Against Racism” and “Jewish Berliners Against Violence in the Middle East.” Citing a likelihood of violence, police have shut down many of these demonstrations. In response, a group of Jewish writers and activists have circulated an open letter insisting on the right to protest. “In an especially absurd case,” reads the letter, which was translated into English and published at the website of the New York literary journal “n+1” by the journalist (and co-organizer) Ben Mauk, “a Jewish Israeli woman was detained for standing alone in a public square while holding a sign denouncing the ongoing war waged by her own country.”

The sign reads, in German: “As a Jew and Israeli, stop the genocide in Gaza.” Police are seen on camera trying to explain that she has to leave because she is not at a political gathering or a demonstration. Exactly, she says — I am not at a demonstration, I am just a person with an opinion. The police answer, in so many words: But what you’re doing has the “character” of a demonstration, and a demonstration about Israel and Gaza is not legal in this location “today.”

They arrest her.

I imagine a fifth Gaza war will prove, like the others, that lethal tensions in the Middle East will not be settled for good by either warring party. They also won’t be calmed by any single, familiar, bitter or long-practiced argument. Stability requires something new, a serious coalition of Israelis and Palestinians with a measure of political power who nevertheless want peace. This precarious future does not yet exist, and I know how idealistic it must sound during a war. The forces against it are clear. But without free debate in an open society — ideally in more than one — it has no chance at all.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.