Lebanon and Northern Ireland are thousands of miles apart, but both regions are known for their divisions and the bloody conflicts these fueled. The civil war was fought in Lebanon from 1975 to 1990, while the “Troubles,” a bloody guerrilla-style war fought among paramilitary groups and the British army, was waged from 1968 to 1998.

Power-sharing arrangements have been adopted to bridge the divisions in the two societies. The Good Friday Agreement and the Lebanese Constitution aim to provide a form of democracy that protects the minority community from the majority — or, in the case of Lebanon, any of the 18 religious groups from one another.

Despite long-running power-sharing arrangements, a durable peace remains elusive in both regions. Northern Ireland and Lebanon have both hit the headlines for their political crises. Lebanon has been without a government for almost a year since the devastating port blast in August 2020 and is facing an economic collapse. In Northern Ireland, a government was finally constituted last year after a three-year hiatus. The period covered almost the entirety of the Brexit negotiations, which will have a seismic effect on the future of the region.

The Good Friday Agreement brokered in 1998 between nationalist Catholics, who identified as Irish, and unionist Protestants, who identified as British, largely — but never completely — ended sectarian violence in Northern Ireland.

The Agreement ensured that the minority, nationalist community has a role in government through the D’Hondt system. The system uses a formula based on a party’s electoral strength to allocate ministries in the cabinet, known as the Executive, and seats in parliament, known as Stormont. This means that the largest unionist and nationalist party must form a coalition.

Since 2003, the Christian fundamentalist Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) has been the leading unionist party, while Sinn Féin, a left-wing party founded as the political arm of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), has been the leading nationalist party.

Despite almost 25 years of a supposedly cross-community political system, Northern Ireland remains divided along Catholic nationalist and Protestant unionist lines. The writer and actor Quentin Crisp quipped that he told an audience of people from Northern Ireland that he was an atheist. In response, one person stood up and asked, “Yes, but is it the God of the Catholics or the God of the Protestants in whom you don’t believe?”

The children of Catholics and Protestants continue to be overwhelmingly segregated by schooling, while some neighborhoods are physically divided by so-called peace walls. In the background, republican and loyalist paramilitary gangs continue to operate with quasi-legitimacy among communities that still refuse to trust one another. Every year approximately 30 people declare themselves homeless in Northern Ireland because of sectarian intimidation in their area.

In Lebanon, a combination of constitutional documents and unwritten conventions guide the power-sharing arrangement. The confessional model that grants power along sectarian lines was introduced by the National Pact in 1943 and was resurrected again by the Taif Accord in 1989. The Taif Accord brokered the end of the civil war and granted the Muslim community a greater share of political power. In 2008, the Doha Agreement was negotiated to prevent another sectarian war. Power was rebalanced to reflect the growing influence of the Shiite Muslim community in Lebanon, represented politically by the Amal Movement and Hezbollah.

However, robust demographic data has never driven the allocation of power. The last official census was in 1932, when Christians held a slim majority. Political parties, with their entrenched positions, are not keen to open the Pandora’s box of an official census any time soon.

The current power-sharing arrangement allocates high-level offices, cabinet and legislative seats, and government jobs to the different religious groups.

Legislative seats are divided equally between Muslim and Christian groups, despite Christians estimated to represent only about a third of the population now. By convention, the office of the prime minister is held by a Sunni Muslim, the office of the president is held by a Christian Maronite, and the office of speaker of the parliament is held by a Shiite Muslim. This is a more rigid allocation of power than in Northern Ireland where, for example, the leader of any party, whether nationalist or unionist, that achieved the highest share of the vote could become the first minister (i.e. the prime minister).

It’s now more than 30 years since the civil war ended, and Lebanon is in the midst of one of the worst economic crises seen globally since the 1850s. Three decades of consociationalism power-sharing and yet many communities remain religiously segregated, with town officials seemingly unafraid and unashamed to introduce express bans on renting property to members of other religions.

Political dynasties maintain a hold on power and, according to international watchdogs, corruption levels in Lebanon have significantly increased in recent years. The “wasta” system of personal connections continues to pervade the delivery of public services, and there is little accountability and oversight in government. No one in the government has been held responsible for the port blast that killed over 200 people and destroyed the homes and livelihoods of more than 300,000.

In Northern Ireland, when the power-sharing arrangement between nationalist and unionist parties collapses, the region is governed by the civil service or ruled directly by the U.K. Parliament. Unlike Northern Ireland, Lebanon is — at least technically — a sovereign state; there is no outside power that can formally step in when parties refuse to form a government. Instead, the previous technocratic government led by Hassan Diab has remained in place as a caretaker but lacks the power to enact the reforms required to unlock international aid.

In both regions, the collapse of power sharing means voters lack the representation and government that would be expected to prevail in a peaceful society.

The term “power sharing” inaccurately implies an egalitarian arrangement. In reality, what is at play in Lebanon and Northern Ireland is power distribution. The political groups come together to decide how power will be divided under the agreed rules before retreating to rule their respective fiefdoms. The formation of a coalition and negotiation of ministries is a large part of the ecumenical activities that the parties are expected to undertake. Yet even that has become an almost seismic feat for the two nations.

The latest political stalemate in Lebanon was preceded by a 29-month period where the country had no president because of a standoff between Saad al-Hariri, the prime minister and leader of the Sunni Future Movement Bloc, and Michel Aoun and the Christian Free Patriotic Movement (FPM). In 2016, Aoun was finally elected as president with the backing of Hezbollah in parliament.

After resigning in 2019 following the start of the anti-government protests in Lebanon, al-Hariri was asked by Aoun in October 2020 to form a government. Al-Hariri proposed a cabinet of experts to enact a program of reforms. Sunni, Shiite and Christian groups would be responsible for one-third of ministries each with no single group holding a veto power in the cabinet (i.e. one-third of ministries plus one).

The proposal was supported by the international community, in particular France, which has promised billions in international aid in return for reforms. The reforms would, however, require the political class to forgo some of the power and influence that it currently wields through the patronage and “wasta” system.

The FPM rejected the proposal over the lack of veto for Christian groups, suggesting this is a violation of the Lebanese Constitution and protecting its control of the interior and justice ministries. In the middle of July, al-Hariri resigned.

The constitutional debate is muddied by the (possibly deliberate) vagueness of the provisions of the Taif Accord regarding the division of power between the president and prime minister and the appointment of the cabinet. What is clear, however, is that the current power-sharing arrangement is not fit if it incentivizes the development of a failed state over government formation.

In Northern Ireland, the coalition of unionist and nationalist parties in the cabinet, as mandated under the Good Friday Agreement, has collapsed five times since 1999.

The most recent three-year breakdown from 2017 to 2020 was triggered by a renewable energy scandal involving the DUP and its opposition to Irish language legislation — an important issue for the nationalist community that mostly identifies as Irish. The tacit agreement of the former DUP leader Edwin Poots to introduce such legislation in June, however, quickly led to his ousting by party members dogmatic in their opposition to Irish culture.

This latest collapse was preceded by a breakdown in power sharing from 2002 to 2007. That was triggered when evidence emerged that Sinn Féin continued to have links with Republican paramilitary groups that were perceived as not fully committed to decommissioning their arms.

The mandatory coalition prescribed by the Good Friday Agreement relies on an overly optimistic level of good relations between political parties given the fraught history and polarized positions of the DUP and Sinn Féin.

The breakdowns in power sharing have a corrosive effect on public services and policy in Northern Ireland. During a collapse, existing policies need to be continued, despite any flaws, and new policies cannot be implemented by civil servants who lack the requisite ministerial power and government oversight. During the most recent impasse, #WeDeserveBetter was a trending hashtag on social media.

There was also public outrage that veto powers designed to prevent oppressive legislation against Catholic or Protestant communities were routinely used by the DUP to stop legislation on abortion and LGBTQ rights.

The D’Hondt system also means that control of the prized ministries of economy, finance and education have almost entirely swung between the DUP and Sinn Féin since the first government was formed under the Good Friday Agreement. It’s no accident that less than 10% of children in Northern Ireland attend integrated schools when control of the Department of Education swings between the two parties who benefit the most from polarized communities.

Brexit has also put significant pressure on the delicate arrangement created under the Good Friday Agreement. In 1998, both the U.K. and Ireland were members of the EU, which eased the dismantling of the hard border between the Republic and Northern Ireland.

The border issue has now become a major flashpoint in EU-U.K. relations post-Brexit. In order to avoid the return of a hard border, a customs border in the Irish Sea between the rest of the U.K. and Northern Ireland had been agreed upon by the EU and the U.K. Some unionist groups viewed this as an unacceptable step toward a united Ireland — which is, of course, the main aim of nationalist parties in Northern Ireland.

The way power is distributed in Northern Ireland and Lebanon makes it relatively easy for one political party or group to bring down or stall a government or policy for their own benefit, but it’s nearly impossible for the public to achieve the same.

When al-Hariri resigned as prime minister in 2019, protesters knew that his resignation alone would never be enough to disrupt the system of power while the rest of the political establishment remained in place. “All of them means all of them” was a common refrain at marches.

Al-Hariri has once again resigned from his position as prime minister in what remained an unchanged political system. Of course, Aoun and Speaker Nabih Berri never left.

In Northern Ireland and Lebanon, anyone who thinks change might come when a politician leaves office often finds that a son or a spouse appears in his place instead (and it is almost always his). The names Robinson, Poots and Dodds have frequently appeared on the ballot in Northern Ireland while al-Hariri, Jumblatt and Frangieh similarly repeat in Lebanon. The situation brings to mind Greek mythology’s Hydra, a snakelike monster with nine heads. When one head is cut off, two more emerge.

The fact that voters in Lebanon are registered in their family town rather than where they live entrenches the power of political dynasties. Despite the introduction of a form of proportional representation for the last elections in Lebanon in 2018, few candidates without sectarian connections have a meaningful chance of being elected.

Former militia members also inevitably form part of the political establishment after a conflict. Why else would they give up their arms? But the continued presence of paramilitary groups long after a conflict reinforces distrust and puts peace out of reach.

Republican and loyalist paramilitary groups continue to operate in deprived communities in Northern Ireland where they’re heavily involved in the drug trade. Hezbollah maintains a network of armed groups, often better equipped than the Lebanese Armed Forces, and tensions between Christian groups over alliances with the Iran-backed Shiite group has led to armed clashes in recent years.

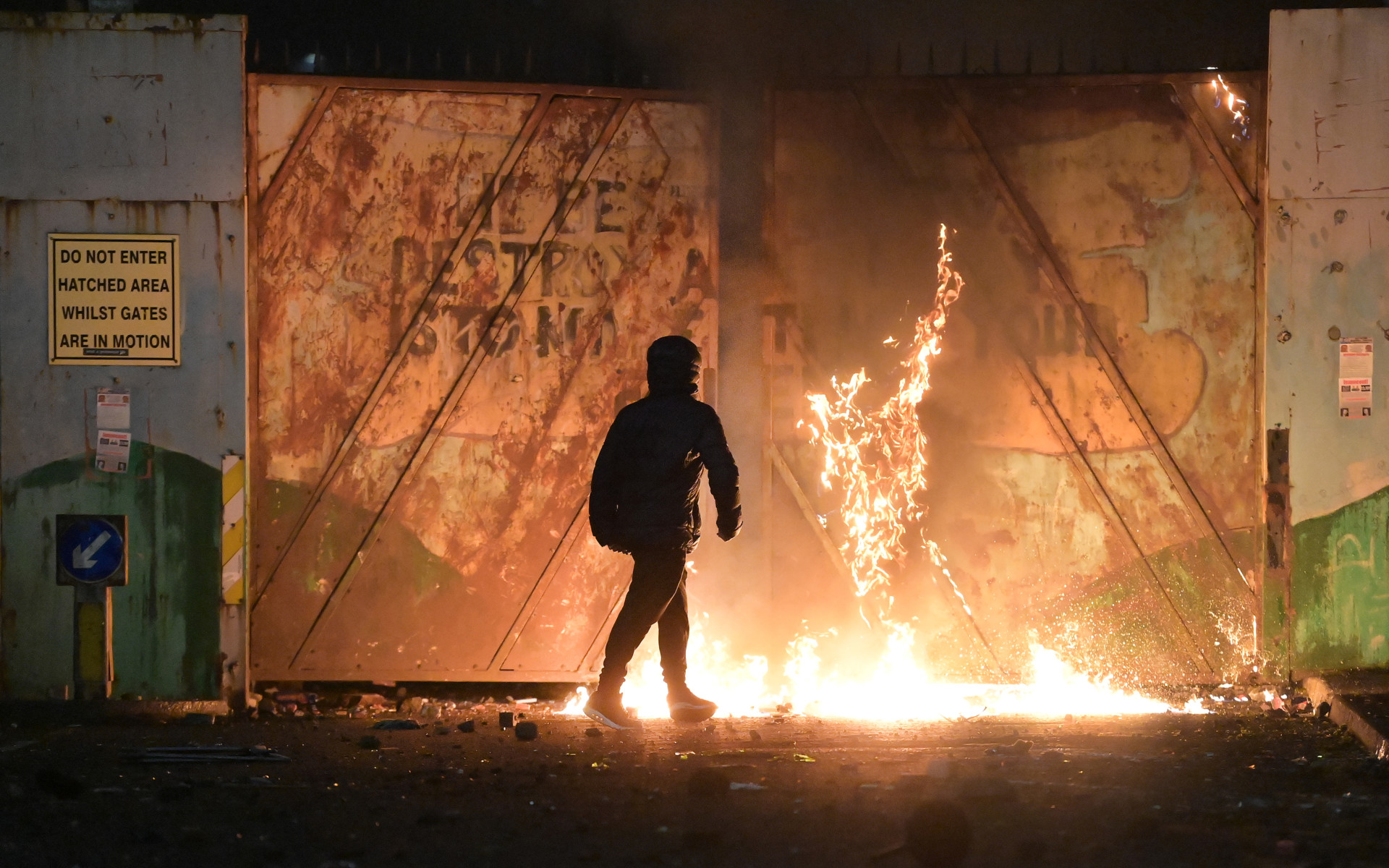

Lokman Slim, a prominent critic of Hezbollah, was murdered in Beirut in February. Meanwhile, young people from working-class unionist communities, encouraged by paramilitary gangs, clashed violently with police on the streets of Belfast and Londonderry in April.

The violence in April was partly provoked by Sinn Féin leaders attending the funeral of a notorious member of the IRA, in a flagrant breach of COVID-19 measures. Sinn Féin’s need to pay their respects to militant republicanism outweighed their commitment to the government and the wider public.

The writer and journalist Patrick Radden Keefe highlighted the divisive nature of this clan-based system in his book on the Troubles: “Outrage is conditioned not by the nature of the atrocity but by the affiliation of the victim and the perpetrator.” What happened is never as important as whether it was “your kind” or “their kind” who did it.

Conflict-era divisions have become entrenched in the political systems of Northern Ireland and Lebanon and are now protecting political parties more than they’re promoting peace.

The democratic trade-off in power-sharing arrangements is always explained by the lives saved from conflicts ending. But lives are lost to poverty, corruption and negligence too, as viscerally seen with the port explosion in Beirut last August. Decades of power sharing should foster trust and deliver opportunities for citizens, not just politicians.