A year after she converted to Islam, Sinead O’Connor appeared on RTÉ’s “The Late Late Show” to perform “Nothing Compares 2 U,” the song that had catapulted her into global stardom in 1990. The iconic Irish singer, who died this week at a mere 56, had not followed the path of other converts to Islam, who in a rush to reinvent themselves often abandon old lives for a joyless piety. In an interview that preceded the performance, it was clear that her recent travails had done little to diminish her spirit. She was as funny, profane and candid as ever. She was working on new music and preparing for a global tour.

Life and fate, however, were setting her up for another fall. First came the pandemic, which scuppered the tour, then the January 2022 suicide of her 17-year-old son, Shane, which sent her spiraling. O’Connor had confronted the first with typical grace, deciding to retrain as a healthcare professional; the latter devastated her.

Sinead O’Connor’s life had been defined by such reversals. After a difficult childhood in Dublin with an abusive mother, she had been sent to An Grianan, an institution for troubled young women run by Catholic nuns. There her extraordinary talent was spotted by music teacher Jeannette Byrne, who bought Sinead her first guitar and later invited her to sing at her wedding. Her voice captured the attention of Jeannette’s brother, Paul Byrne, whose band In Tua Nua was looking for a singer. Paul gave her a tape and within a day she had prepared the lyrics and melody. The mix of kindness and cruelty she had experienced from the nuns became the material for her first recorded song. “Take My Hand” drew from the times when as a punishment Sinead had been required to spend the night in the hospice of a Magdalene asylum, the Catholic-run sanctuaries that housed Ireland’s “fallen women.” Some of these women were rape victims, some impregnated by the powerful, all of them wasting away in their cloistered disgrace.

The transcendent quality in O’Connor’s voice is already there in “Take My Hand,” but it is mournful and controlled. It is only after moving to London that she would also find her rage and, consequently, her range — from tender to ferocious, fragile to fierce, and every shade of emotion in between. Her encounters with Portobello Road’s Rastafarians also broadened her responses to injustice: It was no longer enough to simply rue it; she would henceforth rage against it.

The art was electric and the artist out of the ordinary. The record company had a goose in its hands whose natural talent, irrepressible presence, ethereal beauty and undeniable charisma seemed to guarantee a lifetime of golden eggs. But the talent was of a piece with the attitude, and the rebellious sensibility wasn’t about to yield to the expectations of industry suits. Before her first record was out, O’Connor had shaved off her hair and was pregnant with a child. Defying record company executives, she kept her child, turned her shaved head into an iconic identity and produced a record of such originality and scope that it endures as one of the greatest debuts in rock history. “The Lion and the Cobra” was certified gold and the song “Mandinka” earned O’Connor her first Grammy nomination.

If “The Lion and the Cobra” had established her artistic bona fides, it was her 1990 album “I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got” that confirmed her status as a global icon. The record had many memorable songs, but it was O’Connor’s rendition of a throwaway track from a Prince side project, “Nothing Compares 2 U,” that catapulted her into superstardom. The record sold 7 million copies, and the song has never been off the airwaves.

Yet by 2020 the once-invincible rebel had been diagnosed with PTSD and had spent years in psychiatric treatment, which had left her with only about $10,000 in her account. In her long struggle against injustice, exploitation and abuse, she had found few allies. But in vilifying and ostracizing her, many of her fellow artists and much of America’s entertainment industry revealed their small-mindedness, narrow ambitions and blinkered provincialism.

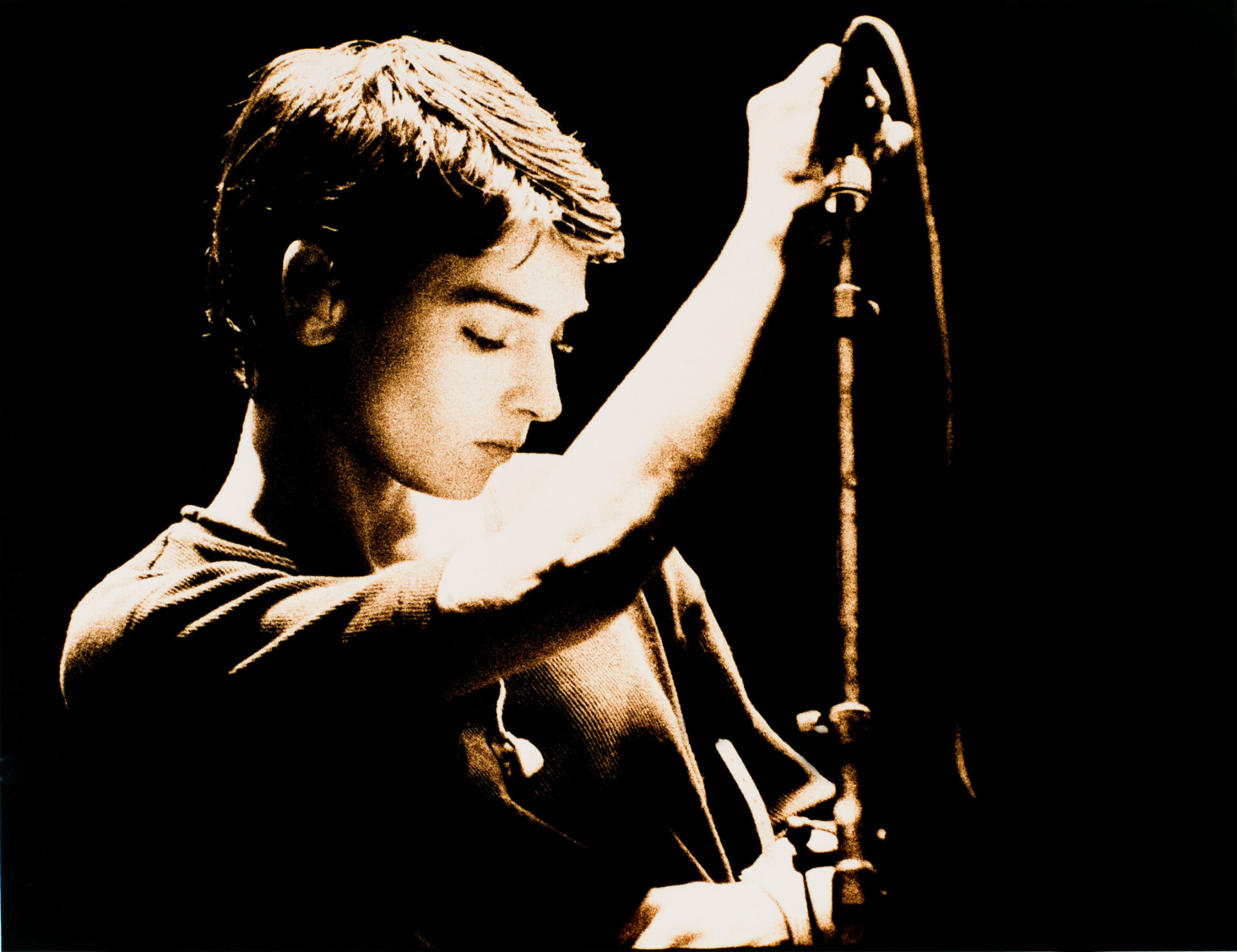

O’Connor was never meant to be a pop artist. She described herself as a “punk,” a “protest singer.” And she embodied that role, regardless of the consequences. Her dissent was not indiscriminate; it wasn’t a posture. She picked big battles. At her 1989 Grammy performance, the young singer appeared with the Public Enemy logo painted onto the side of her head to protest the Grammy’s refusal to recognize rap as a legitimate genre as well as her son’s onesie tied behind her jeans, a statement against record executives’ suggestion that motherhood was incompatible with a music career.

Her second album secured four Grammy nominations, but she refused to attend the ceremony in protest against the Gulf War. In New Jersey, she riled American patriots by refusing to perform if the “Star-Spangled Banner” was played at the event. And then came the infamous “Saturday Night Live” (SNL) moment, when after an a capella performance of Bob Marley’s “War” (with lyrics amended for the occasion), she made a statement in support of the children whose abuse had been hushed up by the Roman Catholic Church. She capped the performance by ripping a picture of Pope John Paul II that her mother once hung on her wall.

The responses were telling. Americans calling themselves patriots drove bulldozers over her CDs, radio stations stopped playing her songs, and many picketed stores selling her music. Frank Sinatra threatened to “kick her ass”; rapper MC Hammer offered to pay her ticket back to Ireland; SNL banned her for life and a week later invited Joe Pesci, who bragged in a monologue about how he would have given her “such a smack” (SNL has erased all records of O’Connor’s performance, but the Pesci monologue is still on its official website); David Letterman hosted obscure comedians to make crude jokes about her appearance; and still bitter at her heavily marketed album being upstaged by O’Connor’s, Madonna used her own SNL performance to mock her and, amid efforts to promote her book “Sex” and her new album “Erotica,” chided O’Connor for hurting Christian feelings.

But the rebel was not about to be undone. When O’Connor traveled back to Ireland, she sent the bill for her flight to MC Hammer (whose money failed to be where his mouth was); she donned a wig and attended a protest against herself and, using a fake American accent, had great fun denouncing her own actions to a television crew. She dismissed the suggestion that the SNL protest had derailed her career: “I feel that having a No 1 record derailed my career,” she countered. The response to Sinatra was delivered by her father, who said that “at his age, [Sinatra] couldn’t kick his leg high enough.” (O’Connor got the last laugh when 10 years later Ol’ Blue Eyes was dead while she was the star guest at Dublin’s annual Sinatra Ball.)

The moment of truth came days after the SNL incident, when O’Connor was invited to sing at Madison Square Garden for a celebration of Bob Dylan’s career. She was meant to perform Dylan’s “I Believe in You” to the packed audience; but half of it started booing. In a video of the event, you can see her taken aback by the response. She paces the stage before returning to the mic and instead of the Dylan song, launches into a furious version of Marley’s “War,” the song she had sung on SNL. The organizers sent Kris Kristofferson to stop the performance, but instead he gave her a hug and told her: “Don’t let the bastards get you down.”

“I am not down,” the rebel replied. But she did walk away from stardom.

Even as the music icon receded, the rebel carried on. She spoke out against wars, spoke up for rape victims being denied abortion, championed abused children and denounced police brutality. And two months after the SNL incident, in response to an appeal from the Red Cross, she donated her $750,000 Hollywood mansion to help famine-stricken children in Somalia. Ten years later, the Boston Globe published a series of reports exposing the scale of abuse inside the Catholic Church (an investigative triumph dramatically rendered in the 2015 movie “Spotlight”). In 2010, Pope Benedict XVI finally apologized for the years of abuse that the church had tried to conceal. No apologies were offered to O’Connor, either by the church or by the entertainers who had abused her. Nor has SNL yet done so.

Meanwhile O’Connor’s health suffered. And after a traumatic hysterectomy in 2015, her mental health declined. In 2017, she caused much alarm when she posted a 12-minute video admitting to suicidal thoughts. A year later, she appears to have found peace in Islam. Islam, too, appears to have found a generous interpreter in O’Connor. In her memoir, she writes: “I’ve done only one holy thing in my life and that was sing”; and to her “The Koran is like a song” and God “an incredible songwriter.”

She reveals that her journey to Islam began in song. She had been playing the call to prayer at her events for years. “The language and intelligence of the call to prayer led me to listen to the Koran,” she wrote. “I was home. I’d been a Muslim all my life and never realized it.”

She took to wearing the hijab because “I like representing. Because Islam gets a hard time.” For her it was a marker of both identity and solidarity. She would have as easily discarded it had someone tried to force it on her.

“I don’t think anyone should be forced to wear hijab,” she wrote. “But I don’t think anyone should be forced not to wear it either.” She made her choice. “Everything I wear to work is a statement.”

She could be the kind of Muslim she became because she lived in a place with religious tolerance (secured in large part by rebels like her). It is doubtful that she would have liked the social conservatism of many Muslim societies. Had she grown up in one, she would have rebelled against it. In Iran, she would have burned the hijab. Islam in the West is tolerant largely because it is separated from power.

Sinead O’Connor never did anything halfway. She defined an age, creating an iconic image and reinventing its sounds. She embodied a form of uncompromising artistry that is becoming rarer with each passing decade. She was grunge before there was grunge; a punk who could speak to angels, a balladeer who could summon demons. From eclectic influences she created a style all her own. She drew on sources both sacred and profane.

Like her compatriot Bono, she assimilated Dylan and Springsteen as well as the Scriptures. But where U2’s music is defined by its earnest devotional quality, hers was Joycean in its subversiveness; where U2 embraced stardom and became inoffensive, O’Connor saw celebrity as a burden and increasingly challenged her audience. When both came together to record a song for the 1993 Daniel Day-Lewis film “In the Name of the Father,” they created magic.

Sinead’s art was inseparable from her politics. It was born of both experience and need. She called it a substitute for therapy, but it was also the hammer she used to try to dismantle the structures that had disfigured her life and those of others. Conscious of her own fragility, she had created something immortal that would endure. Because even if the bastards did get her down, the imperishable part of her would still rebel on.

O’Connor was possessed of a generous spirit. In a postscript to her 2021 memoir “Rememberings,” she directly addressed her father, thanked him for his love and absolves both him and her mother of any responsibility for her traumas. She forgave her mother, seeing in her a fellow victim, who was as much in need of kindness as she was. But unlike her mother, her rage was directed both inward and outward; and unlike her mother’s, it was not indiscriminate. In the end, the William Butler Yeats verse she drew on to describe her mother’s unfocused rage better describes the long wars of her own short life.

What could have made her peaceful with a mind

That nobleness made simple as a fire,

With beauty like a tightened bow, a kind

That is not natural in an age like this,

Being high and solitary and most stern?

Why, what could she have done, being what she is?

Was there another Troy for her to burn?