While in prison, the Russian artist Alexandra Skochilenko, who goes by Sasha, found traces of humanity and tenderness in the cracks of the Kremlin’s increasingly repressive system.

Despite the relentless propaganda from state media portraying anti-war Russians as enemies rooting for the demise of their own country, Skochilenko, an openly gay liberal arts school graduate from an intellectual background, could count only four out of a hundred fellow prisoners who were vehemently in favor of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Others viewed the war with resignation, as a folly of President Vladimir Putin over which they have no control.

The 33-year-old was one of a dozen Russian dissidents who were released from prisons and flown to safety in Germany on Aug. 1, as part of the largest exchange of inmates between Russia and the West since the Cold War era drew to a close.

In the Spring of 2022, shortly after the full-scale invasion, Skochilenko was jailed for seven years for sneaking small anti-war messages into supermarkets. “They wanted to make an example of me and to scare everyone else,” she told New Lines in an extensive interview by video call from Koblenz in western Germany, where Skochilenko was offered medical screening by the German government as part of the exchange, and where she is staying put for now.

Skochilenko, who has long wavy auburn hair and a penchant for tie-dyed T-shirts, described how most of her cellmates at St. Petersburg’s Arsenalka detention center were genuinely perplexed by the absurdity of the charges against her. “Surely, that’s just a mistake and they will probably let you go soon,” they often told her.

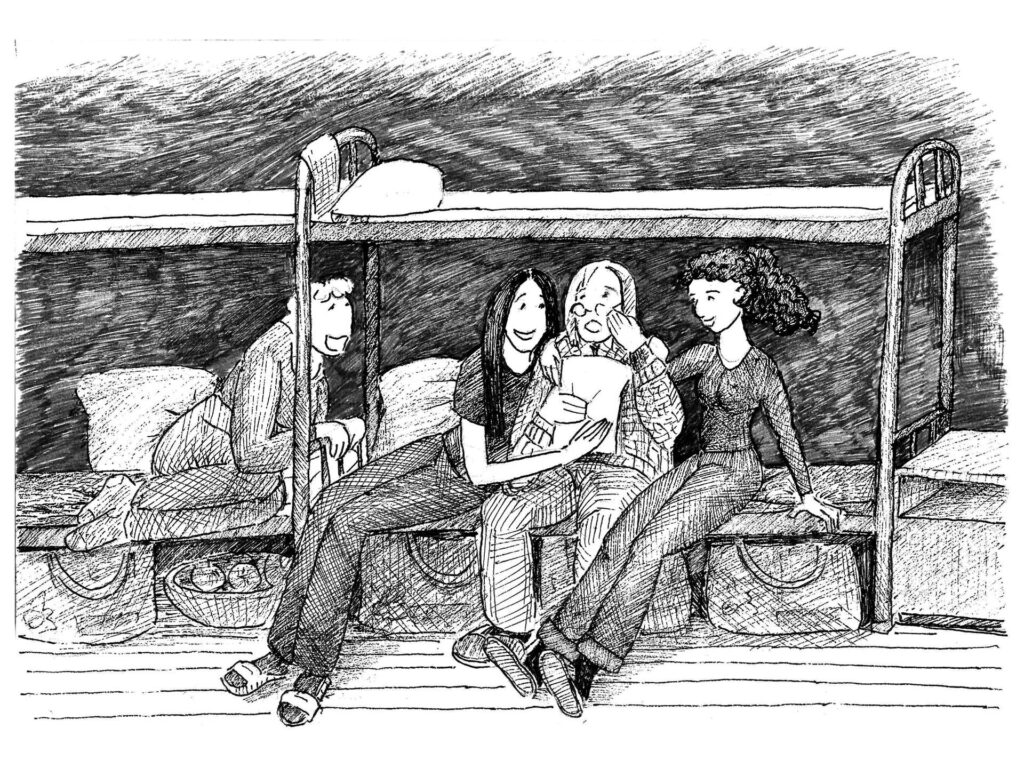

She was joined in Germany by her partner of five years, Sonya Subbotina, and the couple now live in leafy Koblenz, a far cry from her cold, damp cell in St. Petersburg, where up to 18 prisoners were crammed on bunk beds, and where she was allowed to go outside for just one hour of each day. She was part of a prisoner swap including Russian assassin Vadim Krasikov, deep-cover Russian spies, Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich and U.S. Marine Paul Whelan.

A few days after the war started in February of 2022, Skochilenko, who is bipolar, was in a manic phase, which she said means she had boundless energy and little thought for the consequences of her actions. Feeling utterly helpless about her country’s attack on Ukraine, she photoshopped five ordinary price tags, replaced the goods’ names with anti-war messages and printed them out.

She then went to a few local supermarkets and swapped out the real price tags for her own. One of them said: “My great-grandfather didn’t fight in WWII for four years for Russia to become a fascist state and attack Ukraine.” (In Russia, the price tags are much larger than in most other countries).

Another was more snappy: “The price for this war is our kids’ lives.”

The stunt felt insignificant at the time — it was certainly not a major anti-Kremlin declaration — and Skochilenko didn’t even mention it to her family. But a few weeks later, the price tags were spotted in one supermarket and traced back to her thanks to CCTV cameras.

Unlike seasoned political opposition figures and veteran dissidents like Ilya Yashin and Oleg Orlov, who were jailed for their anti-war activism after the Kremlin failed to push them into exile, the once-obscure artist from St. Petersburg was not at all mentally prepared to spend two years behind bars. And now that she is free, she also finds herself ill-prepared for freedom.

With her physical health now mostly under control — she suffers from a heart defect and celiac disease — she is more concerned about her mental state. She was told by therapists in both Germany and Russia that the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) she likely developed in prison would become more acute in the months to come and would require attention. “I know I’m still in the shock phase and it’s too early to work on it,” Skochilenko said, adding that she is going to “crisis sessions” with a therapist, talking through daily events around her “just to make it through one week after another.”

Skochilenko struggles with flashbacks and triggers from her life as a prison inmate. She is afraid of the dark and keeps the light on. Sonya often has to go out of the house and check outside when Sasha is spooked by a noise or a mysterious silhouette. “I always think it’s the police,” she said with a resigned smile. Although she knows perfectly well that German police have no interest in jailing her, Skochilenko is still triggered by uniformed men and their vehicles.

“The other day we were in a park and a police van pulled up. I thought: ‘Maybe we’ve jaywalked too much?’”

She knows it’s a long road, but takes solace in the splinters of light and empathy she discovered along the way.

Some prison guards were even openly sympathetic to the artist. “One of them turned off CCTV when he walked into my cell and told me: ‘I have a lot of respect for what you did. I would have done the same if I could.’”

There were also investigators who shared her outrage about the invasion and Russian war crimes but thought her gesture was futile: “Don’t you feel sorry that you threw … years of your life down the drain? You could not have changed anything,” one of them told her during a pretrial interrogation.

Despite her health issues and deprivation in prison, she is clearly putting on a brave face. “I guess if my story has changed at least one person working in Russian law enforcement, it was already worth it,” Skochilenko said as she described her ordeal as her “coolest art performance.”

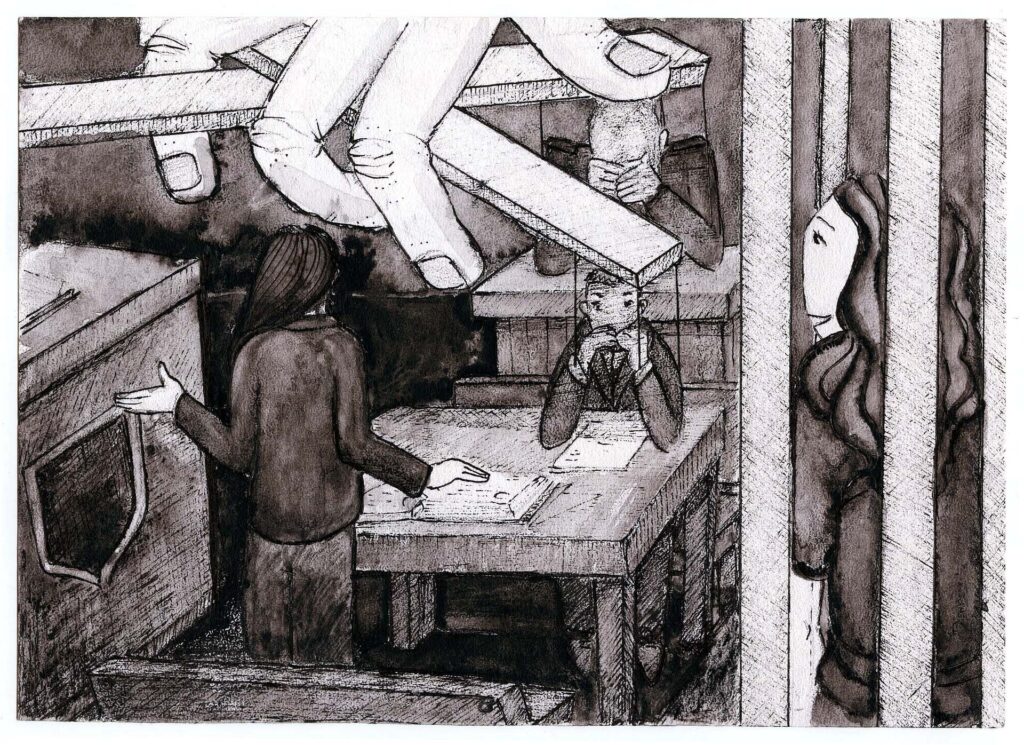

Drawing was one of the things that kept Skochilenko going while in prison.

She made myriad sketches — both in color and black-and-white — of her life there: Cats basking in the sun by barbed wire, prison yard walks, and self-portraits in which she is holding a peace sign-shaped pendant. Some of them were mailed to supporters who then posted the sketches online. Subbotina campaigned for her release. But like her compatriots, Skochilenko was placed on the list for the swap without her say.

Before she was transferred to a Moscow prison ahead of the prisoner swap in July, Skochilenko made sure to give all the sketches to someone for safekeeping — she would not say how she did it exactly out of fear of safety for them.

“Making art in Russia has become impossible for me: I often make art about love and I speak of my love for Sonya. But these days you can’t openly talk about it in Russia.”

Repression against all forms of dissent in Russia took a much darker turn in February 2022 when Putin unleashed the invasion of Ukraine and promptly pushed through legislation that practically outlawed any form of criticism of the war or even public expressions of doubt about its goals. The start of the invasion triggered a flurry of impromptu street protests across Russia but a steady crackdown on the opposition in the preceding months made sure the numbers were low.

Many ordinary Russians, however, were in such agony over the invasion that they looked for any possible outlet to express their outrage, from scrawling anti-war graffiti in the street to hacking government websites. Skochilenko, too, was in pain from the images and stories of her country’s army killing and pillaging in Ukraine: “I was overwhelmed with emotions: Pain, sadness, shame,” she says.

The war felt personal to the St. Petersburg artist who just a few years earlier was invited to teach film to teenagers in a summer camp in Ukraine. When it began, she would go online and flicker through Instagram stories of her former students showing the new normality of war in Ukraine: air raids, bombed-out houses, people cooking food on a campfire instead of their stoves. “I was sitting there in Russia, and all those kids I used to take care of were now hiding from bombs in basements. How could I stay silent about it?”

In another twist of fate, after years of failing to place her graphic novel about fighting depression — in Russia, conversations about mental health are still an uncomfortable subject for the general population — Skochilenko was able to publish it in Ukraine in 2019. She was now picturing her book behind shop windows shuttered in anticipation of another Russian attack.

Skochilenko, who worked for several years as a videographer for a St. Petersburg news website that covered opposition protests, was no stranger to Russia’s police state. But she could never imagine that this small act of defiance could actually lead to a high-profile criminal case and a lengthy prison sentence. Alexander Bastrykin, Putin’s university classmate and head of Russia’s Investigative Committee, was in town when the price tags story first surfaced and reportedly took the case under his personal supervision.

She was arrested at around the same time that Russian state TV producer Marina Ovsyannikova disrupted a prime-time news broadcast with an anti-war stunt and a contemporary artist staged a Moscow street performance to condemn the massacre in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha.

At the end of a trial that lasted several months, Skochilenko was handed down the lengthy sentence after she was found guilty of spreading “fake news” about the Russian armed forces, a new addition to Russian legislation hastily passed a week after the invasion.

Skochilenko differs from other Russian political prisoners who were pardoned — and essentially deported from their home country — because she doesn’t feel she could go back if she were allowed. “Even if I were released from prison in Russia, it would be too dangerous for me to stay there,” she said, citing her impending marriage to her long-term girlfriend Sonya.

She refers to Russia as an abusive partner whom she had tolerated for too long. Being gay has become a hazard in her country, which recently saw a sweeping crackdown on gay clubs and publications in line with a decade-old antigay bill that had been largely dormant for most of that time.

Skochilenko’s family worried about her health: without medical treatment, she could have died in prison. Her gluten intolerance also meant she often did not have enough suitable food to eat. After she and other Russian dissidents were flown into Germany, Skochilenko and her partner Sonya decided to stay in Koblenz, where they were offered political asylum.

Now, she is enjoying simple things: touching the grass and looking at open skies. “I’m only just beginning to process what happened to me: Right now I’m just marveling at the world.”

She is also waiting for her sketches to be brought to Germany, where she will begin working on a comic strip book about her prison ordeal. Skochilenko is waiting to start her proper PTSD therapy and embark on her project once she is feeling better.

Although the incarceration at times seemed never-ending, Skochilenko knew she did not want to put the book together until she was free and her story was, in a way, over. “I didn’t want to tell this story while I was an object of violence — I wanted to be an actor who shows her agency in tough moments, which helps you to survive and not break down,” she said.

“I want to win back my agency. This is what a traumatized person suffers from.”

But before she gets down to work, Skochilenko wants to enjoy a normal routine: getting groceries, cooking for her partner and doing laundry in a washing machine, not in a tiny sink in a prison bathroom. “It’s a miracle,” she said of life’s simple pleasures.

They are daily reminders that, unlike others who were in jail at the same time, she did not choose this way of life.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.