“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.

There is a Syrian expression that is used to denote something as being especially old or outdated: “from the time of Seferberlik.” It is perhaps too anodyne an expression, referring as it does to one of the great crimes against humanity of the 20th century, perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire in its Levantine and Kurdish territories.

Seferberlik is the name given to the mass mobilization in the Ottoman provinces to aid the sultanate in its Balkan conflicts and World War I, a campaign that saw the conscription of thousands of Arabs and Kurds in the Levant and its environs, and the deaths of those who tried to dodge the conscription. The mobilization was ordered by the Ottoman governor of Syria, Ahmed Jamal Pasha, who was otherwise known as “al-Saffah,” a term that describes someone whose wanton slaughter requires less finesse and more cruelty than a butcher possesses. His policies also led directly to the mass starvation in Lebanon of some 200,000 people during the Great War.

Though painful memories from the era endure, Seferberlik and the colonial crimes of the Ottomans in their Arab domains do not occupy the same place in the collective cultural memory of the region as, say, the Armenian genocide. This is perhaps a subject for more well-read scholars to explore and understand, but I would hazard a guess as to two factors. The first is that the post-independence era in the Arab world following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire was rife with its own colonial cruelties perpetrated by Western powers, whether in Syria, Lebanon, Palestine or elsewhere. The second reason is that, with a long-enough temporal distance from the events, many Muslims in the region no longer perceive Ottoman dominance as a colonial enterprise but rather as a zenith just beyond living memory of a powerful and cultured Islamic state whose collapse was instrumental in the scattering of the faith’s power and appeal. This is perhaps part of the reason Turkish soap operas dealing with the Ottoman era have been so popular in the Arab world, driving a surge in Arab tourism in Turkey as well.

Many cracks have appeared in this notional affinity (often not shared by its object, Turkey) over the past decade, due to Ankara’s growing rivalry with regional powers, particularly the Gulf states (excluding Qatar) and Egypt. One of the avenues in which this rivalry has taken shape is TV drama. Syrian soap operas set in the era frequently portray the Ottomans as colonialists, a trend in pop culture that paralleled Turkey’s involvement in Syria’s war as opponents of Bashar al-Assad.

Now, a new high-profile soap opera that has begun airing during Ramadan, unsubtly titled “Safar Barlik” (the Arabic transliteration of the Turkish word), is set to bring this rivalry further into the realm of public consciousness and pop culture, and to lay bare Turkey’s colonial legacy in the region and its cruelty toward its subjects.

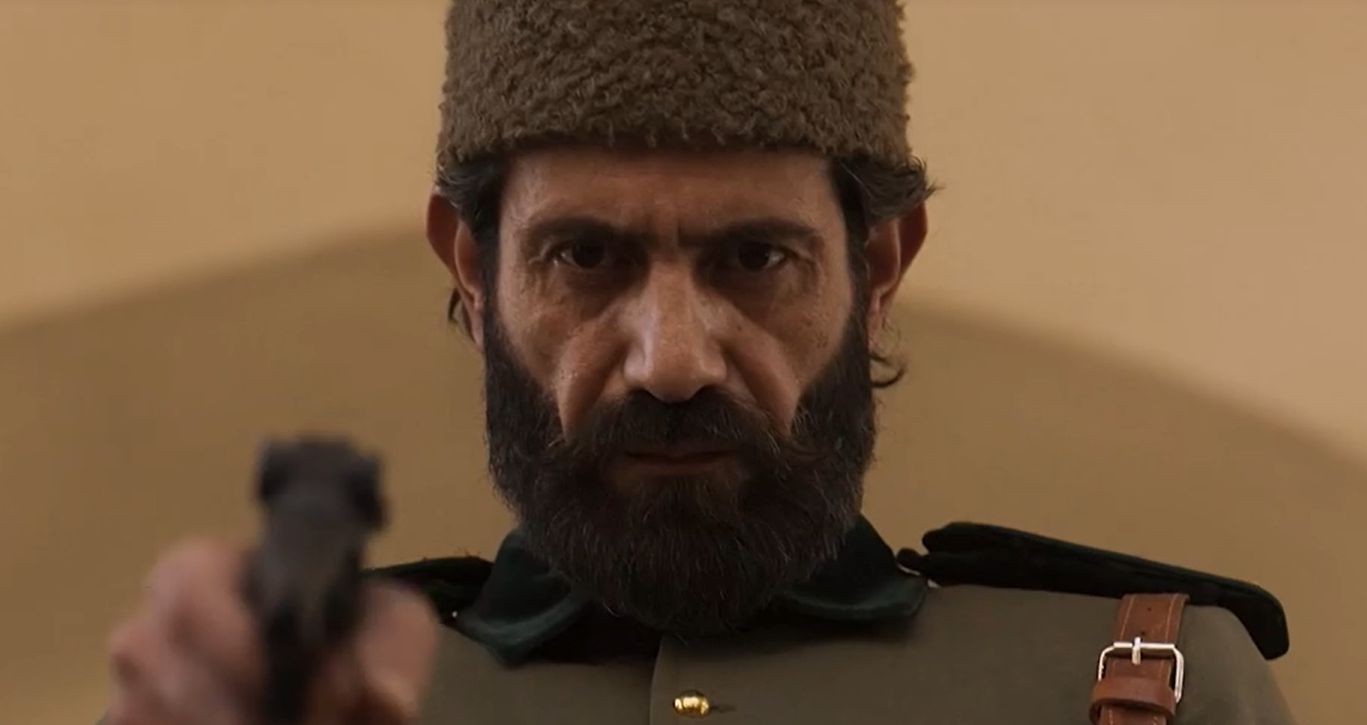

Ramadan soap operas are a popular fixture of the Muslim holy month, when TV viewership typically spikes. The “Safar Barlik” series, which so far has aired two episodes, begins with the scene of a protest in Medina against the Ottoman representative, who proceeds to order his forces to massacre the protesters before shooting one of their leaders point-blank in the head in front of his nephew, all while maintaining a look of seething hatred and scorn at the Arabs under his rule. The episode, titled “Guardians of Blood,” then fast-forwards nine years later. The nephew plans a haphazard assassination attempt against Yuzbashi Ismet, the local governor who killed his uncle, after he returns to Medina. His older brother, Abdul Rahman, who wants nothing to do with politics, counsels against it, saying the Ottoman sultanate was reforming, before leaving to pursue his studies in Istanbul.

The story then continues along two separate tracks. In Istanbul, Abdul Rahman’s roommate, also from the region that would become Saudi Arabia, is involved in activist circles calling for greater rights and autonomy in the Ottomans’ Arab provinces and proudly references the ongoing campaign by the kingdom’s founder, Ibn Saud, against the Ottomans and his conquest of al-Ihsa with just 600 men. After the assassination of Mahmud Sevkat Pasha, a former war minister and key power broker in Beyazit Square in Istanbul, Arab students are rounded up, and Abdul Rahman is abused and beaten in a Turkish police station. Simultaneously, his younger brother botches an assassination attempt against the local Ottoman governor, and his security forces rampage through the streets of Medina, beating and arresting ordinary civilians. Despite the abuse, Abdul Rahman remains reluctant to take a political position against the Ottoman state, reasoning that the actions of individuals should not impinge on an entire edifice that upholds the Islamic faith and is beset by foreign enemies. This belief is put to the test at the end of the second episode, when he and his roommate are chased by a Turk with whom they had had an altercation through the streets of Istanbul, and the roommate is shot dead.

The series is peppered with moments that lay bare the intention of its showrunners in portraying the Ottoman Empire as an oppressive colonialist entity. When Abdul Rahman cautions his brother to abandon thoughts of revenge for their martyred uncle, arguing that the Ottomans were instituting wide-ranging reforms, his brother Radwan responds: “We haven’t seen any benefit to these reforms. A snake is a snake even if it changes its skin.” After he returns from Medina, his roommate argues that the Ottomans are the reason the Arab world lagged behind the rest of the world: “A corrupt state, all that we’ve gotten out of it is oppression, ignorance, poverty. Look where the world is now and where we are.”

In a moment of despair after his torture, Abdul Rahman himself questions why he was so savagely assaulted, his feet held up and beaten with a so-called “falaka,” a rod commonly used for torture in the region. He tells his roommate: “They didn’t just beat me. They stood on me, on my dignity. They were monsters. All of this for no reason.” His roommate responds that his identity itself was the reason: “The reason is clear, as I am your brother. You are an Arab, Abdul Rahman, and they are foreigners who want to erase you from existence.”

“Safar Barlik” is airing on MBC, a television network headquartered in Riyadh, whose top executives came under the radar of Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman’s corruption investigations after years of trying to purchase the then-Dubai-based network outright. It was recently involved in a controversy over the planned airing of a Ramadan series about Muawiya, the first Umayyad caliph and a hated figure among Shiite Muslims. The series was canceled over the possibility of sparking a diplomatic incident between Riyadh and Baghdad, whose rapprochement has been credited with reducing sectarian violence.

Saudi Arabia’s relationship with Turkey is more complicated. The two countries have been at odds for over a decade because of Ankara’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood. Turkey leaked details of Saudi agents’ involvement in the assassination of the writer Jamal Khashoggi at the kingdom’s consulate in Istanbul in 2018 and held a trial for those involved. The rivalry also took shape within popular culture and consciousness, with a decline in Arab tourism to Turkey, general hostility in talk shows and political commentary, and a ban on Turkish soap operas on MBC back in 2018.

In late 2017, the Emirati foreign minister, Abdullah bin Zayed, retweeted a post accusing Fakhreddin Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Medina in 1916, who is likely to feature in “Safar Barlik,” of crimes against the local population. In response, the Turkish government renamed the street in Ankara on which the UAE Embassy is based to Fakhreddin Pasha street.

Saudi Arabia and its partners, the UAE and Egypt, have more recently engaged in a rapprochement with Turkey. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan visited Riyadh and shook hands with the crown prince, and both Gulf states have invested billions to shore up the embattled Turkish economy.

But the series shows that these rivalries and bad blood are not so easily buried. Perhaps the region’s leaders may be happy to smile and forget the recent past, but there is clearly an appetite to remember the more distant past. The entrenchment of Turkey’s image as an abusive colonial overlord is likely to have far-reaching repercussions and to complicate the regional realignment that is taking place today.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.