General Power bounded into the backyard of Pennoh Building, one of Monrovia’s grimiest drug slums, and was welcomed with drumming and chanting as users smoked away. He had come in recent weeks to recruit people for his drug rehabilitation program; on this occasion, he demanded two young women come with him. One man offered his girlfriend; another young woman in a short dress stepped forward. The two were soon whisked away in an army-green four-wheel drive, taken back to a clandestine facility manned by Liberian army veterans like Power himself. In contrast to the handful of drug rehabilitation centers operating in Liberia, at Power’s facility the patients, or “inmates” as he refers to them, are locked behind bars, beaten with canes and placed in solitary confinement.

With 249 men, women, girls and boys inside its walls, Power’s is the largest drug rehabilitation program in the country and has been operating for two years without any government oversight. The government officials involved in the fight against drugs with whom I spoke claimed to know nothing about it. Leaders in the police and military knew of Power’s center but claimed to know little about the conditions in the facility. Few questioned Power, an ally of former President George Weah’s government who was a feared fighter in the country’s civil war and who has played a shadowy role in the security sector since the 2014 Ebola virus outbreak.

At the facility, two men, recovering addicts themselves, shaved the women’s heads — a requirement of Power’s. One of the women cried as the razor scraped away her curls. An older inmate warned them jokingly about the beatings and told the woman she would get used to it. Soon, the two women would be put on intravenous drips of rehydration solution as part of their detoxification. One convulsed, the other fell asleep in a daze.

The women had been using kush, a cheap, synthetic marijuana that is rolled with tobacco, smoked like a cigarette and is believed to be laced with opioids and other substances. Kush has flooded the drug market in Liberia in recent years. The United Nations Population Fund estimates that at least 20% of young people in Liberia are using substances, including kush. The rehabilitation center run by Power, whose real name is Augustine J. Nagbe, is one of only a handful of such centers that are struggling to address a growing crisis. The nation’s new president, Joseph Boakai, has dubbed it a “public health emergency.” Weah was said to have been voted out of office in part because of his failure to handle the crisis.

The drug use epidemic has been growing in Liberia over the past two years, particularly due to the low cost and availability of kush, which sells for as little as 50 cents per pack.

“Two years ago, it become very rampant. People were dying, people were dying, seriously,” Nagbe told New Lines in Liberian English. “So, people started coming to me, talking to me, and myself, I allowed them to come in,” he said.

Nagbe describes his program as “very military,” an element many parents find reassuring when their children have fallen into addiction. “The parents had confidence in me that I can bring the restriction to the children and I can deal with them in a way to depart from the drugs,” he said.

Inspired by Rodrigo Duterte, the former president of the Philippines who oversaw a period of vigilante violence against both dealers and users of illicit drugs, Nagbe — who served in the country’s military before the war, then during it took “General Power” as his nom de guerre — believes there should be a death penalty for dealers and users over 18 should be sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Nagbe claims his project is largely personally funded, but charges families between $100 and $200 and a bag of rice per month for their relatives’ rehab. They must also provide items like soap, toothbrushes, medication, other food items and bedding. Rehab in Liberia is rarely free, with Nagbe’s prices reflecting the average costs, which are unaffordable for most in a country facing extreme poverty and where half the population lives on less than $1.90 a day. One highly regarded rehabilitation center, named Mother of Light, that provides counseling, activities and training, priced the cost of rehabilitation at $450 a month, which is almost two-thirds of the average annual income in Liberia.

While Nagbe’s center may be the largest, some are skeptical about his intentions. “It’s an avenue for him to get money,” said one Liberian in the diaspora, who had a relative in Nagbe’s center and requested to go unnamed for fear of repercussions. “Parents are so desperate. … He’s not qualified. I don’t see him as a role model,” he said, referring to allegations of Nagbe’s wartime record. In the final report for Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission following the nation’s brutal civil war, Nagbe was listed among the most notorious perpetrators, accused of torture, looting and destruction of property during the conflict. One woman testified that he made her eat a can of feces at gunpoint.

At Nagbe’s rehab center, rattan canes lay around for routine floggings and handcuffs were hooked to the main gate. Men in military uniform communicated with walkie-talkies. Parked along its walls was Nagbe’s fleet: a Hummer, a four-wheel drive truck and an auto rickshaw, all painted in army green and ready to pick up new recruits, voluntary or not.

Though Nagbe has operated his prison-like rehab center for two years, those working on the issue in the Ministry of Health claimed no knowledge of it. Members of Nagbe’s team, including veterans, claimed to be operating with the support of the coast guard. I witnessed soldiers present when inmates were being flogged and saw members of the army and police enter the facility. The Liberian military did not respond for comment.

The building where Nagbe operates was given to him by Nathaniel McGill, a former minister in Weah’s government who was sanctioned by the United States government for corruption in August 2022 and resigned a month later. McGill acknowledged giving the building to Nagbe, but said he had never visited the center. “I think he should be stopped and it should be reported. The place was never given to him to go and beat people,” McGill, who is now a senator, told New Lines.

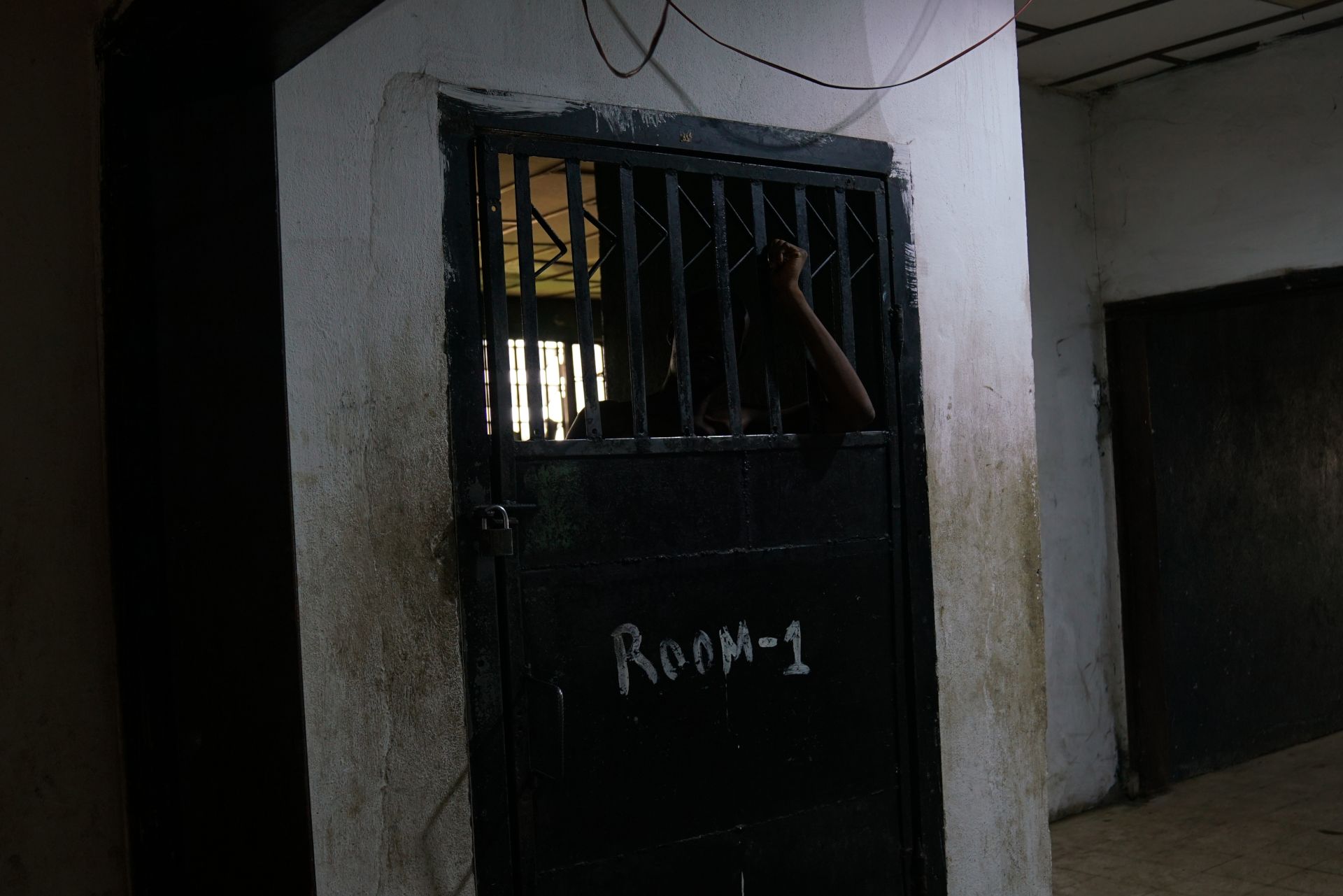

I visited the facility four times from September 2023 and witnessed people being flogged by staff and other inmates, men crammed together in a pitch-black room called “Interview,” and addicts who had their heads and eyebrows shaved — a staff member told me it was so they could be identified as inmates, while a recovering addict said it was so they could be identified in communities if they escaped. “We’re in jail! We want freedom!” a group of teenage boys who were in a cramped cell mixed with adult men yelled to me. Nagbe claims his program runs for three to six months, but he is the one who ultimately decides when those who are held there leave.

Men and teenage boys were mixed in cells and had to urinate in plastic barrels. Those housed in the facility only ate once a day. I saw a man who was handcuffed to a metal grill one morning who was still there in the late afternoon before I left. The men and boys spent most of the days behind bars; the girls and women, who also slept in barred rooms, received training in cooking from a soldier’s widow. Nagbe regularly filmed “inmates” posting their images on his Facebook pages and WhatsApp, in order to promote the center and solicit funding from the government and members of the Liberian diaspora.

Despite the failure of Nagbe’s organization to adhere to a draft protocol that requires voluntary admission for drug rehab treatment, it was given clearance by the Ministry of Health to operate for a year from Aug. 29, 2023 by Dr. Cuallau Jabbeh Howe, who is in charge of approving nongovernmental health organizations in Liberia. For NGOs to be approved they must have a budget and work plan, outline areas of intervention and have a list of health team staff, and there must be a site inspection. Jabbeh Howe told New Lines that she and her team had not inspected the site.

On Jan. 5, I came across Interview, the dark cell that was used for punishment. Through the square slots of the iron door, men asked me to help them and later, when they finally got out, showed me where they had been flogged. One young man was released after five days there because his estranged father, a pastor, had come to visit. I watched as he kneeled on the ground dripping with sweat, pleading for forgiveness during a prayer session in front of staff and other inmates. I would later speak to his father about his son’s decadelong struggles with addiction.

“He began to cry on me to take him out. He has no cause for being in there. He needs to learn, he needs to be talked to, he needs to be counseled, to understand,” the pastor said. “I don’t feel good about it because I see some of the treatment there is inhumane.”

The young man’s mother lives in the United States and had paid for him to be admitted to the center, according to his father. His father wanted him to leave but was uncertain about what the protocol was.

Though General Power’s grim methods appeal to many, it is not the only approach Liberians are taking to rehab. Not far outside of Monrovia, in Grand Bassa county, Mother of Light Liberia welcomes recovering addicts with chickens, a greenhouse, regular meals and counseling sessions. The center, a project with the Ministry of Health and largely funded by Liberia’s wealthy Lebanese business community, has capped numbers at 30, yet also still struggles for funding.

One woman New Lines spoke with, who declined to give her name, had been receiving treatment for three months. “They counsel me, take good care of me, feed me on time,” she said. Patients are over 18 and can leave at any time if they give the center 24 hours’ notice. The woman came to the center because she grew tired of drugs and felt disconnected from “good people” and family. A tattoo reading “All I need is freedom” is etched on her arm and has taken on a new meaning since her rebellious days of doing drugs as a teenager. “The habit I was in, I was not free, but now I am free,” she said.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.