“Can anyone tell me,” began the Belfast-born Jesuit, clad in the black habit of his order, from behind the lectern, “what is an Armalite?”

I knew this one. “It’s a cheap, American-made rifle.”

“Cheap? Cheap! What d’ye mean ‘cheap?’” he barked, tomato-red with feigned indignation, as the whole class erupted.

He had a point. A powerful weapon weighing only 7 pounds, with a collapsible stock, the Armalite is the semiautomatic version of the U.S. Army’s standard-issue M16. It fires a high-velocity .223 round that tumbles in the air and causes gaping, deadly wounds. Affordable, sure. Attainable, definitely — but not cheap.

As a symbol, the Armalite harks back to a moment when it was smuggled in large quantities across the Atlantic Ocean, from America right into the expectant hands of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA). Over three decades, through arms, funds and political agitation, sympathetic elements of Irish America brought their weight to bear upon the decades of bloodletting known as Northern Ireland’s Troubles — a conflict which has, in its cloak-and-dagger intrigue, retained the ability to captivate far beyond both countries.

All the same, Boston College was an eerie setting for that kind of joke. Only a few years before, the university had been swept up in what can only be described as an international incident, after a secret trove of interviews held on its campus, featuring both nationalist and unionist paramilitaries from Northern Ireland, was exposed to the public. The revelations contained within triggered a series of events that formed the basis of Patrick Radden Keefe’s bestselling book “Say Nothing.” In December, FX and Hulu released a critically acclaimed television adaptation of Keefe’s 2018 book, which follows the lives of a clutch of high-level IRA operators as they wage their campaign of political violence across the U.K. At least 3,500 were killed in Northern Ireland’s sectarian violence — a figure, in its scale, equivalent to 600,000 American deaths.

Many Americans are familiar with the broad-brushstrokes account of the Troubles, in large part due to Keefe’s book. But what they don’t know is that the militant republicans on screen were often funded by normal, everyday Irish Americans from the middle and working classes. The donations ranged from suitcases of cash handed over by religious, conservative businesspeople and lawyers to money collected from teachers, electricians, bus drivers and carpenters in jars passed around at pub gatherings and dinner dances. The main vehicle for transporting this money to the “Provos” was an American activist group called the Irish Northern Aid Committee, also known as NORAID. My great-uncle was in NORAID, serving the group as a nationally recognized organizer and spokesman. We’ll call him “Roger.”

NORAID was founded in 1970, hardly a year after the Troubles began in Northern Ireland, when a young, upwardly mobile and university-educated generation of Catholics began to agitate for the rights they felt they were owed. A minority in the six counties of Ulster, they were deprioritized in housing allocation, disenfranchised, blackballed from prominent firms and shut out of entire industries. At times, the Protestant unionist majority could be openly condescending: “It is frightfully hard to explain to Protestants that if you give Roman Catholics a good job and a good house, they will live like Protestants,” said Prime Minister Terence O’Neill to the Belfast Telegraph in 1969. “But if a Roman Catholic is jobless, and lives in the most ghastly hovel, he will rear eighteen children on National Assistance.”

For a generation of Northern Irish activists, the dream of a nonviolent civil rights movement died in the face of loyalist and unionist mob violence. Many nationalists observed that the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), whose members were nearly all Protestant, was openly complicit in sectarian pogroms. As protesters clashed with police and public order disintegrated, the Catholic ghettos of West Belfast and Derry’s Bogside sought the means for self-defense.

As ever in Ireland, officially sanctioned acts of British intransigence and cruelty — like the Falls Curfew of July 1970, when soldiers sealed off a Belfast neighborhood and searched homes and business for weapons, and a policy of mass internment without trial — minted thousands of new militants among the embittered and brutalized denizens of the north, and from the ashes of the old IRA arose the “Provisionals.”

They needed guns and ammunition. And they knew just where to get them.

Irish America, the 19th-century Irish nationalist Michael Davitt declared, would be “the avenging wolf-hound of Irish nationalism.”

The first large waves of Irish immigration to the United States were in the middle of the 19th century, but more than a century later, in the 1970s and ‘80s, Irish-American life was still a tight-knit world, with all the accompanying civic infrastructure. Known as “the Darkness,” or just “Dark,” the leading IRA figure Brendan Hughes first journeyed to the U.S. in 1975, where he procured the group’s initial shipment of Armalite rifles. (“They went Armalite crazy,” recalled one Brooklyn-based gunrunner, to the journalist Jack Holland.) Interviewed in 1975, the New York City Council President Paul O’Dwyer, of the prominent law firm O’Dwyer and Bernstein, pointed out that the majority of Irish guns used in the War of Independence were also sourced in America. (He declined, when asked, to condemn the Provisional IRA.) A crusading liberal, O’Dwyer was representative of a radical republican network that flourished in cities like New York, Boston and Chicago, where my great-uncle was born and reared.

A propaganda item from 1973 describes Roger as an engaging young attorney and energetic second-generation Hibernian, possibly of the Ancient Order of Hibernians — a kind of Elks Lodge for Irish Americans with, in those days, much NORAID overlap. Like the County Mayo-born O’Dwyer, Roger practiced personal injury law, representing just the sort of folks who might donate a dollar for “the boys.” In addition to his professional exploits (he’d recently secured the largest personal injury suit involving a juvenile in Illinois history), he had sought out, on three trips, the Irish-speaking districts of Kerry and Connemara, probably to practice his Gaelic. He had also memorized “over 500 Irish songs and recitations,” and there are precious few songs about the great Irish military victories — an imbalance that might have made an impression upon a young Hibernophile. The Bronx-based Martin Galvin, longtime publicity director for NORAID, plied his trade as an attorney for the city’s Sanitation Department. But the figurehead of this generation was undoubtedly the charismatic elder Michael Flannery, a NORAID founder who had battled the Brits as a teenager before emigrating to America and building a career at New York’s MetLife.

While the British, Irish and American governments strongly contested it, NORAID never diverged from the line that 100% of its funds went to supporting the indigent families of the political prisoners in the north, and Roger was no exception. Speaking to a reporter in 1981, he vociferously denied that one single dollar could be tied to arms, explosives or ammunition, calling it both “laughable” and “ludicrous.” (Though, as Holland points out in “The American Connection,” the distinction is purely academic: In Flannery’s formulation of that time, “an IRA soldier freed from financial worries for his family is a much better fighter!”)

The feds had singled out NORAID, Roger argued, as “the only effective counteractive to British propaganda” in the U.S. The State Department denied visas to Sinn Fein politicians until the 1990s, and the mainstream press was unreliable. The U.K. banned Galvin from entering Northern Ireland, though he did so anyway. Appearing with IRA leaders Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness at a Belfast rally in 1984, Galvin evaded arrest by the RUC, whose rubber bullets killed a bystander (inadvertently proving, again, the republican point about British leadenness). In 1981, Roger was tapped to debate the British consul-general in Chicago, George Chalmers, on NBC 5’s “Chicago Today.” Claiming he had only learned at the last minute that he was to appear with a member of Northern Aid, Chalmers insisted on being interviewed alone — “the subject of much comment,” Roger wrote in The Irish People, a New York-based newspaper that Galvin edited. Fighting the propaganda war and organizing with seeming impunity, prominent Irish-American activists were not just supporting the Provisionals (who had, by that time, carried out an audacious string of bombings, including the assassination of Lord Louis Mountbatten, cousin to Queen Elizabeth II and a mentor to Prince Charles), they were making a mockery of the “special relationship” itself.

Meanwhile, the Justice Department was still trying to coil itself around the arms pipeline, with mixed results. In 1982, Flannery and four others were charged in Manhattan federal court with running weapons to the IRA over a six-month period. Faced with overwhelming evidence against their clients, O’Dwyer’s clever men resolved to steer into the skid, cooking up the cockamamie, brilliant canard that they hadn’t run guns for six months, as the government alleged, but 25 years — a scheme so long-running that the Central Intelligence Agency, which witness testimony had established was all-seeing, simply must have known about it. Improbably, the jury agreed, and acquitted the five men on all counts. Introducing Flannery to a standing ovation at the annual Chicagoland NORAID dinner gala a few weeks later, Roger joked that the Irishman “gave too much credit to the attorneys.”

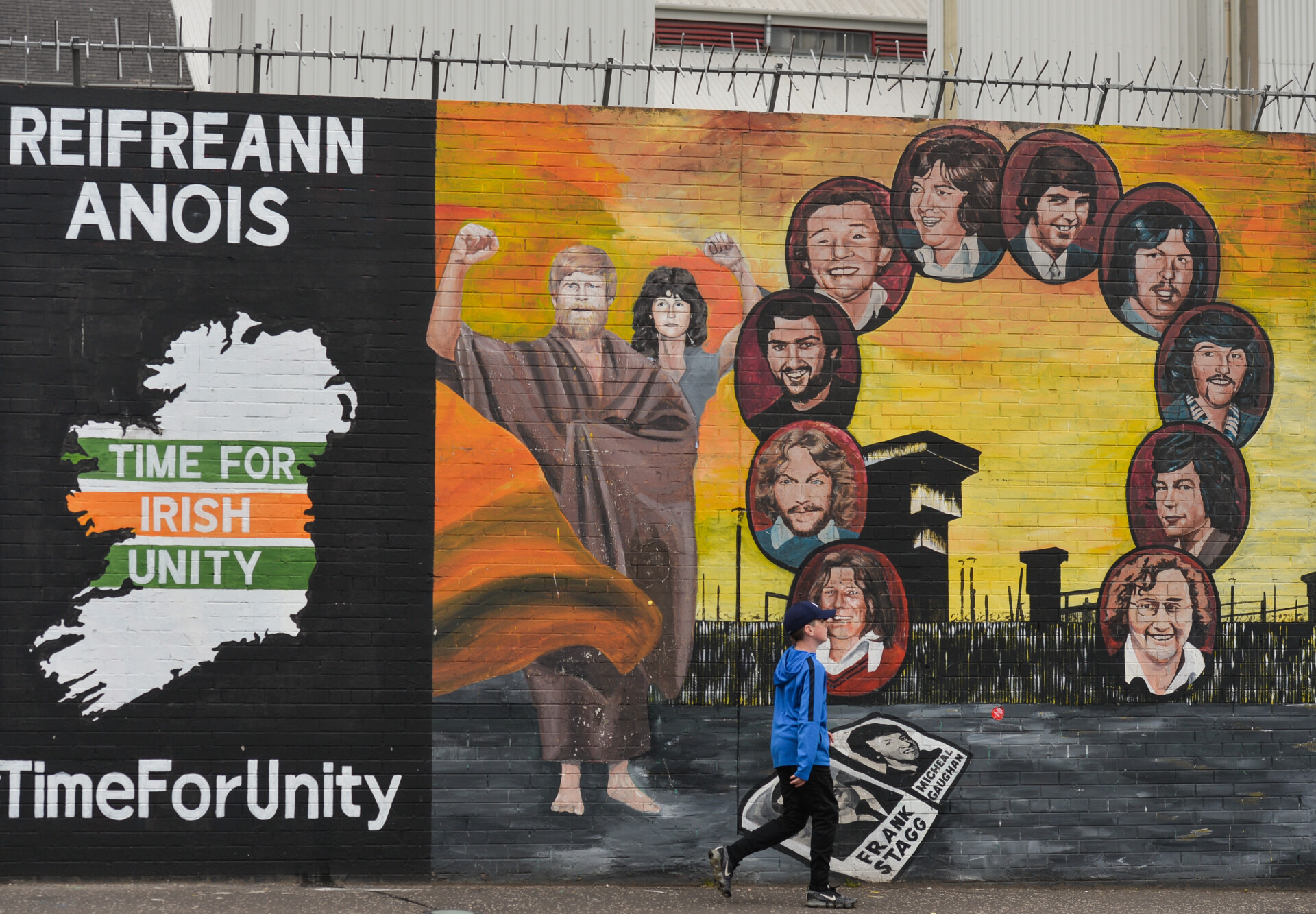

Despite the efforts of multiple governments, NORAID sent millions of dollars to Northern Ireland over the course of the 1970s and 1980s. But the group received an even larger propaganda gift in those years that defined the organization’s activism — the Maze Prison protests.

To protest the British authorities’ decision to class them not as political prisoners but as common criminals — which meant they were denied the right to wear their own clothes and associate freely within the jail — IRA prisoners went “on the blanket,” refusing to dress, wash themselves, or leave their cells. They started smearing their own feces on the walls in triskelion-like spirals.

Later, they went on hunger strike, drawing global sympathy and even the attention of Pope John Paul II. As these protests mounted over the early 1980s, they received overwhelming support among Irish Americans (often led by NORAID) who may have detected some Christ-like imagery in the prisoners’ long, scraggly hair and vanishingly thin forms. Reading Che and Mao, and quizzing each other on the Irish language and republican history, the prisoners’ steadfast refusal and stoic disregard of their own bodies caught the attention of U.S. backers who were more comfortable canvassing for Ronald Reagan than discoursing on anti-imperialist themes. In the week following the death of hunger striker Bobby Sands in May 1981, several thousand people picketed each day outside the British consulate on New York City’s Fifth Avenue. At NORAID-sponsored events in Illinois and Indiana, Roger appeared alongside former IRA Chief of Staff John Joe McGirl and the families of hunger strikers like Joe McDonnell, reading, before hushed audiences, letters smuggled out of prison from the so-called “blanketmen.” All the while, NORAID coffers expanded in a surge of public support not seen since the early 1970s.

But larger political developments would soon eclipse the armed struggle entirely. As the 1980s progressed, the IRA doubled down on its political direction in the form of Sinn Fein, and a new American group cropped up, called Friends of Sinn Fein (FoSF). Clean of any connection to armed struggle, FoSF was a superior vehicle for approaching Wall Street’s Irish-American nouveau riche. “Sinn Fein,” writes the journalist Ed Moloney in “A Secret History of the IRA,” “[had] moved out of the backrooms of bars in the Bronx into the boardrooms of Park Avenue.” When Adams finally got his visa from Bill Clinton’s government in the 1990s and came to New York City, Flannery, Galvin and other NORAIDers were snubbed.

“Some had gone to jail for their activities,” writes Moloney. “Now they could be forgiven for thinking that Adams had turned his back on them.”

If it’s true, as the saying has it, that “God made the Catholics, but the Armalite made them equal,” then it must also be true that the Armalite could not, by itself, let them be at peace. The political route spearheaded by Adams that baffled so many NORAID activists in America eventually led to him shaking hands with Tony Blair — when, not 15 years earlier, the IRA had come within a hair of killing a different prime minister, Margaret Thatcher.

During the Troubles, many Irish Americans identified Britain as responsible for not only their own emigration and their ancestors’, but for continuing to mistreat their distant cousins up north, and for obstructing the ideal of a united Ireland. With the teaching of the American Revolution in U.S. schools, “rebels against the crown” took on, for many, a kind of dual meaning. “Would you condemn your George Washington?” asked Flannery of New York Governor Hugh Carey in 1983. O’Dwyer and Flannery, very old men by the 1990s, died in that decade. And once a diehard critic of Sinn Fein’s turn — like most of Keefe’s subjects in “Say Nothing” — Galvin came, eventually, to endorse it. The gun, he felt, was too long gone from Irish politics to be anything but destructive of peaceful ends. Pursued jointly by the British, Irish and American governments, along with the parties of Northern Ireland, the Good Friday Agreement is one of the all-time great victories for multilateralism. With their own two feet in these communities, it’s clear that Adams and McGuinness could see much further down the pike than their radical American counterparts. The ultimate verdict on their decisions has been a quarter-century of peace.

As for my great-uncle Roger, his record of activism dries up in the mid-1980s. He left his firm around that time to set up his own practice. Maybe he felt the movement was strong enough without him. Perhaps he was disillusioned. In any case, he died before I could learn anything more. But those who knew him have echoed what many say — that there was no appetite for even the most abstracted armed struggle following 9/11. Besides, Irish America is not what it used to be; it is more diffuse and polarized along familiar, domestic political lines, with “Irish Americans for Harris-Walz” on one side and Kellyanne Conway, Mick Mulvaney and Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. on the other.

NORAID’s role and its ensuing redundancy directly challenge the notion that we can cast world conflicts and their belligerents as actors in our own stateside morality plays. It reveals both the limits of diasporic politics, and the politics of war as spectator sport. The former correspondent Aris Roussinos argued after the start of the Ukraine war that we were beginning to witness the final, terrible synthesis of high-definition combat footage (often captured by drones) and social media, transforming armed conflict into entertainment and social media users into partisan consumers of violent death and destruction. Social media, in particular, provides the illusion of intimate familiarity: More than ever, we see videos of faraway upheaval and feel we know who is to blame for what without stepping beyond our own thresholds.

Paradoxically, one of the subtle dividends of peace in Northern Ireland has been, on either side of the Atlantic, a cottage industry dedicated to a form of antiquarian appreciation of that period. As glimpsed in a world-conquering series like Derry Girls, the Troubles are seemingly shorn of their capacity to polarize, threaten or anger. The “openly republican” Belfast rap group Kneecap can play shows all over the world, debut a film at Cannes and use rebel imagery throughout while eliciting little more than an angry tweet.

Milan Kundera has written that in “the sunset of dissolution, everything is illuminated by the aura of nostalgia, even the guillotine.”

Even the Armalite.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.