“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers every Monday and Wednesday. Sign up here.

For days after polls closed in Nigeria’s presidential election this February, the nation held its breath, waiting for results to be announced. Despite promises from the country’s electoral commission that the vote would be free and fair, the election had been arguably disastrous. There were numerous reports of political violence and voter suppression all over the country; new voting technology was riddled with errors, keeping votes from being uploaded and tallied quickly; accusations of votes being altered in broad daylight abounded. What had seemed like the emergence of a new political dawn was beginning to feel — for many of the young Nigerians who had increased their political participation this year — like a return to the country’s corrupt ways.

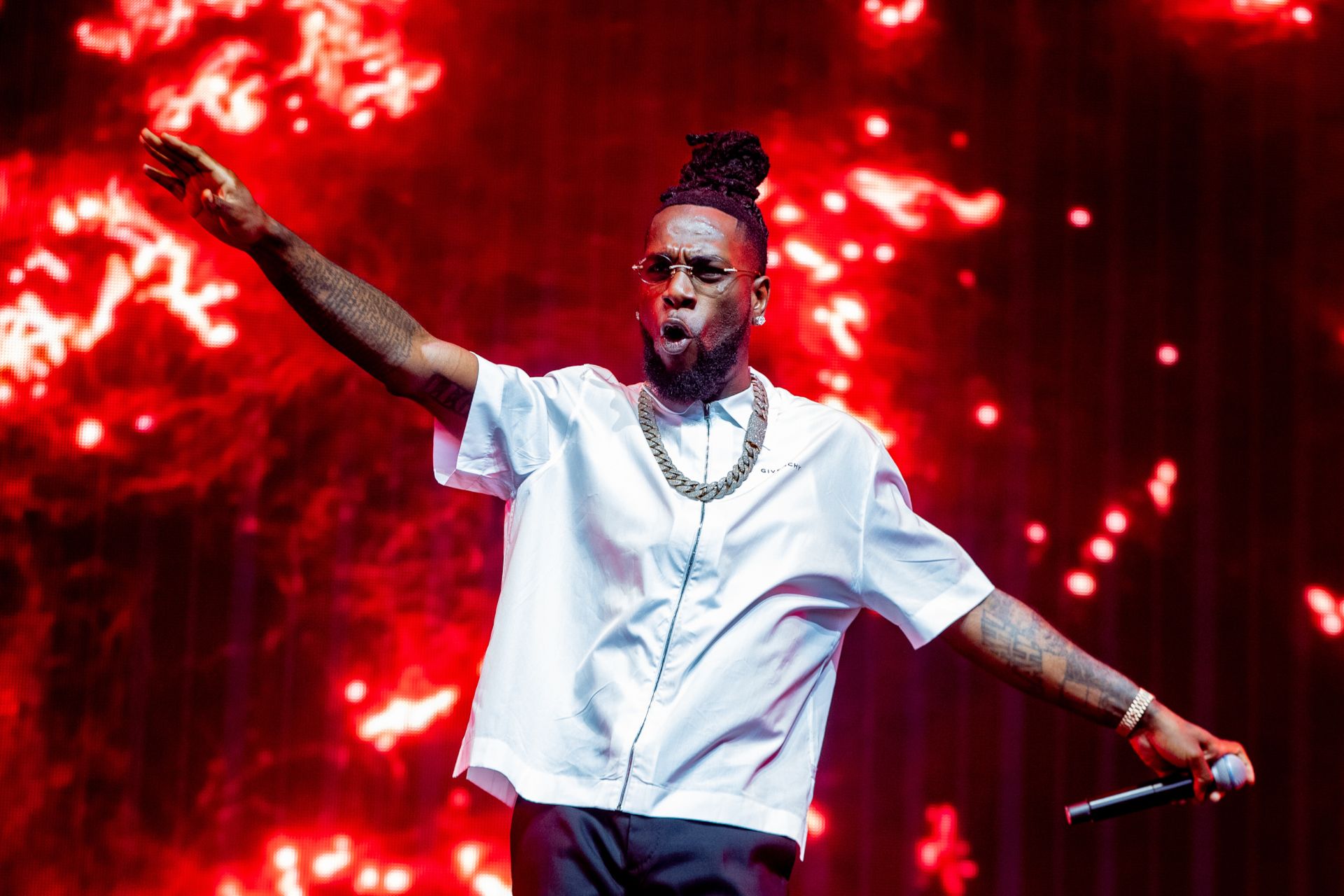

Two days into that nervous wait, the Nigerian Afrobeats superstar Burna Boy posted on his Instagram account.

“I dunno why it’s such a big deal to some Nigerians that I’ve not been vocal about the elections,” he said. “Personally, I don’t have a candidate that I believe in. I’ve never supported any political party or candidate in my life because I don’t want to make you vote and then blame me when the person fucks up as usual. That being said, I hope all votes count and the best man wins.”

But for many of his fans, Burna’s silence — and the casual dismissal that followed it — was a big deal. It was uncharacteristic of an artist who has built his career on criticizing corrupt governance, unpacking the role of colonialism and aspiring toward Black unity on the global front through his music. So why had the Grammy award winner, who has been hailed in the West as the voice of his generation and who had been vocal during the #EndSARS protests — the nationwide youth-led movement against police brutality that broke out in October 2020 (the hashtag slogan means “End the Special Anti-Robbery Squad,” a notoriously abusive police unit) — now met his country’s biggest election in a generation with a shrug?

Since he exploded on the Afrobeats scene with the release of his hit single “Like to Party” from his debut album “L.I.F.E. (Leaving an Impact for Eternity),” Burna has shifted between personas. He was philosophical in his first album, then he was a bad-reputation artist in his sophomore “On a Spaceship.” In between, he made politically charged music once in a while. In his debut album, there was “My Cry,” a biting social commentary on Nigeria’s corruption. “Just the dirty politicians/ Just give them a pen and the money goes missing,” he sings. Then there was “Soke,” a slow-burning party starter that unpacked Nigeria’s poverty. “E no easy/ No money o, no light e o, water nko? E no dey flow,” he sings, alluding to the deplorable state of things in the country with the lack of stable electricity, running water and other necessities.

Over the years, Burna has moved from making these sometimes subtle, often irregular political statements through his songs to creating works heavily defined by them. In 2019, he released “African Giant,” an illustrious work that traverses the various planes of his political concerns. On it, he lists some of Nigeria’s darkest political structures before finally announcing himself as a politically conscious artist in a way he hadn’t before. Take “Collateral Damage,” the ninth track on the album, in which he ruminates on the country’s deplorable political climate: “Ambassador go dey chop/And Governor go dey chop/And President go dey chop/ When dem say make we jump, we go jump,” he sings at the opening, alluding to the persistent corrupt practices of Nigeria’s political class.

When “African Giant” was released, many found the work timely, laden with the kind of message and themes that were part of the zeitgeist. Others found his politics hazy and lacking in precise messaging. Though he wove sociopolitical issues into his lyrics, he did so with the distance of an observer.

Unlike his idol, Fela Kuti, the Nigerian star of the 1970s whose politically charged music was a huge affront to the government, Burna’s politics have always seemed to begin and end in his music. While Kuti regularly put his body on the line, lending his weight to anti-corruption movements and offering a bold, thoughtful critique of anti-Blackness and corruption through his music, Burna’s lyrics stay on the surface. In a way, he functions more as an archivist than as an independent thinker.

Burna has said openly that he is not a political activist of any sort; instead, he describes himself as someone who sees the truth and isn’t afraid to say it. But that is curious, considering how often he borrows and designs his own artistic image from Kuti, an artist who never sugarcoated his political engagement in his music and daily life.

As the writer Saratu Morolayo told me, Burna Boy, “just like us, is a bewildered witness; even in his music, he’s not a leader and, to his credit, hasn’t put himself forward as one. I think the mask has long slipped, though, in terms of seeing him as some kind of political artist. He’s not. That’s just fine, as he has a right to be political or not, but we as the audience have a right to see it as an image-shaping exercise that has no root in his desire to be part of any social or political cause.”

In truth, Burna’s politics have been beneficial only as a vehicle for his crossover to the West. In the United States and Europe — where he has headlined major events like the NBA All-Star Game and received top billing at the recent Coachella music festival — he is seen as a deeply political artist and pan-African champion quick to align himself with the possibility of global Black unity.

So is he an activist or an opportunist?

Take “Monsters You Made,” an impassioned song decrying government ineptitude. The track, from his 2020 album “Twice as Tall,” includes a clip of famous Ghanaian author Amaa Ata Aidoo criticizing colonialism — but it also features Coldplay’s Chris Martin, a choice that is hard to digest on a song about postcolonial ills. While the idea of a white man singing a song criticizing a global structure refined by his country over centuries might not make much sense to many, a collaboration with a much-loved pop star proved to be a smart business move for Burna: “Twice as Tall” won him a Grammy that year.

Afrobeats music, which fuses West African musical styles with funk, soul and jazz in an infectious confluence of culture and sound, has always been political. Just like Kuti, artists from various generations have made music that attacked poor government administration, captured the poverty in the country and served as a way for them to attempt to make a change.

When the legendary rapper Eedris Abdulkareem made “Jaga Jaga,” he painted a harrowing image of how difficult it was and still is to live in Nigeria. “Nigeria jagajaga/Everything scatter scatter/Poor man dey suffer suffer,” he sang.

Timaya, another Afrobeats artist, memorialized the killing of his people, who were clamoring for rights to the oil resources that came from their region, in a track called “Dem Mama”:

“I swear I no go forget am oh/ When them kill the people oh/ And they make the children them orphans oh.”

The genuine concern these artists feel about the decline in living conditions in Nigeria and their disgust at government corruption carry through in their music. They continue to call out the government boldly in their work, even when, as in the case of Abdulkareem, it gets them arrested. More crucially, they never intentionally seek to form an image by speaking out.

“In Burna’s case, the hypocrisy is more glaring,” Morolayo said, “because he chooses to sing some politically conscious songs to shape his image, especially abroad and especially during that ‘African Giant’ press run. It looks far too much like hypocrisy as a result.”

In recent times, conscious music has taken a nosedive in Nigeria. Only a handful of artists like the rapper Falz — who has constantly moved his political engagement away from his music to the streets, joining protests and urging voter participation — come to mind. Yet despite the work he has done and continues to do, Falz has hardly ever attempted to capitalize off this image in the way Burna ostensibly has. During the #EndSARS protests, although he eventually spoke out — buying billboard space to promote the anti-police brutality message and making a song to memorialize the protesters shot by the military — Burna was hounded about his silence before he took action.

Perhaps the public and his fans are foisting on Burna the kind of political responsibility he doesn’t have the range for, despite his casting himself in the likeness of a famously politically conscious artist. Perhaps the best lesson one can take from Burna’s recent and past political apathy is to focus solely on his music. Seeing him for the artist he is — crafty with his sound and occasionally concerned about politics for reasons best known to him — will save us all from lofty expectations.

As the writer Wilfred Okiche told me, “You just listen to the music and you shouldn’t deny yourself of listening to his music and you shouldn’t deny his talent.

“But you should also know that this guy is not a spokesperson for any cause,” he continues. “It is nice when he speaks out, but it is nicer if he were speaking when it is genuine as opposed to people practically forcing him. We don’t expect you to be our hero, just do your music. That’s why we came to you in the first place.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.