“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.

On Jan. 21, the most popular pop star in the Arab world, Amr Diab, performed at an open-air venue in Dubai. Screaming fans sang along as he belted out classics and newer hits (which generally sound pretty similar). Diab, who deserves the moniker megastar, is a beneficiary of Dubai’s drive to reinvent itself from a onetime shopping destination into a cultural, scientific and technological mecca for the region. In the process, Dubai has initiated projects as varied as a nascent space program that has sent a probe to Mars to so-called “golden visas” and residencies to luring social media influencers.

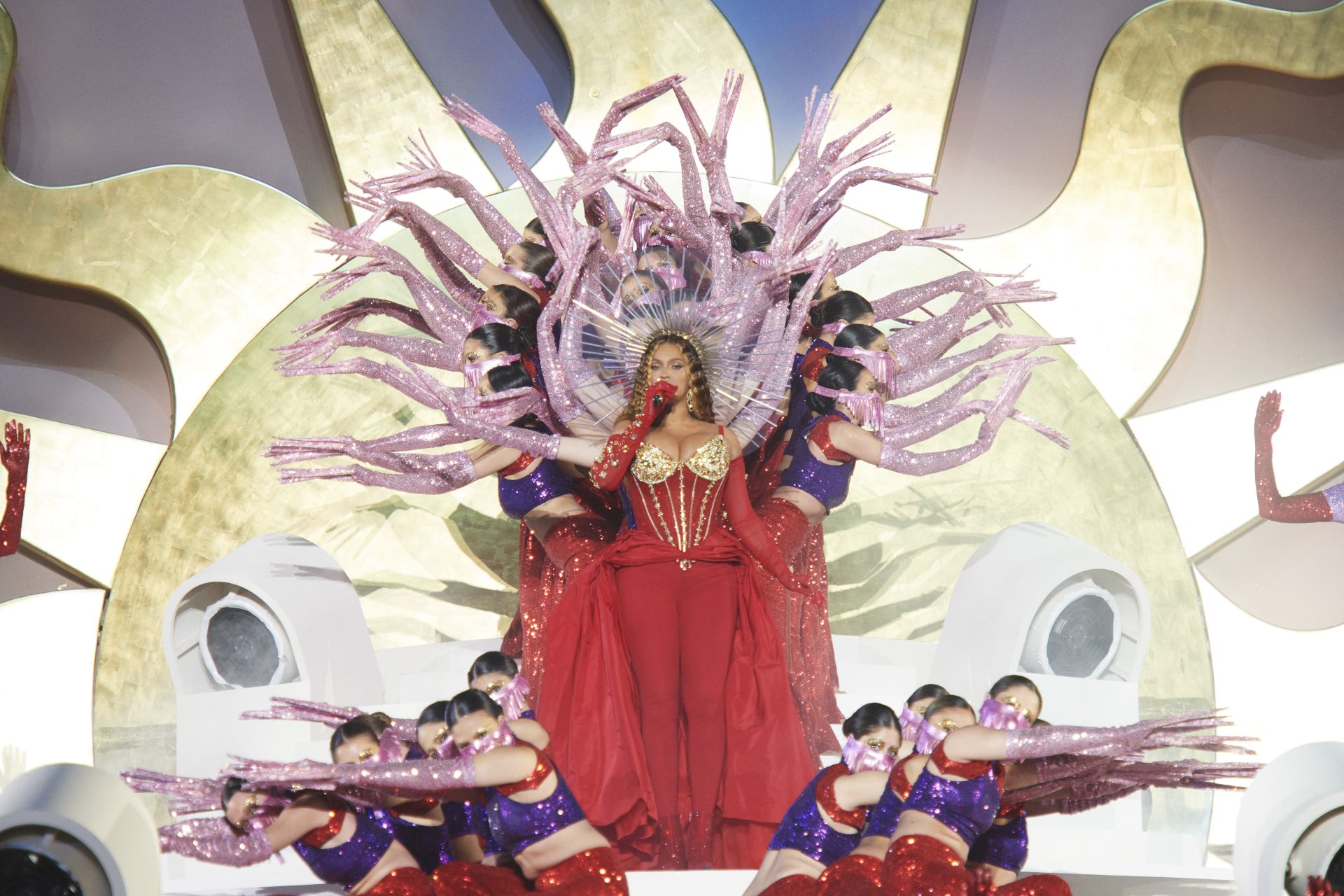

But Diab was not the main attraction of the weekend. Elsewhere in the city, Queen B herself, Beyoncé, took to the stage after a four-year hiatus to perform at an exclusive invite-only party featuring hundreds of celebrities and socialites to mark the opening of Atlantis The Royal, Dubai’s latest landmark, a seafront million-square-foot hotel that cost $1.4 billion to build. Beyoncé, who was joined onstage by her daughter, reportedly received $24 million for the launch, which also featured celebrity model Kendall Jenner, who was there to promote her 818 Tequila, which had been selected as the hotel’s official tequila drink.

The event represents Dubai at its most cliched, and perhaps most comfortable, state of opulence. Amid the fame and glitz, it also breaks random world records, including, in the hotel’s water park, having the largest number of water slides in one location, subject both to envy and disdain by onlookers. In many ways it is the epitome of the influencer culture that the city has cultivated deliberately, with multitudes of major and minor online celebrities advocating for causes that matter to the city and the UAE at large, be it the promotion of a brand or edifice, or political stance.

But it is also fascinating for its insight into the culture of online activism and social pressure, and the particularities of the Middle East as its powerhouses — whether the liberal UAE or the conservative Saudi Arabia and Qatar — seek also to bask in the glitz of Western celebrity culture. It raises serious questions about the viability of online activism and protest as well as why the Middle East in particular seems to attract calls for cultural boycott.

Beyoncé was criticized on social and mainstream media for performing in Dubai because of the UAE’s human rights record, particularly on LGBT rights, since gay relationships are still outlawed in the country despite its liberal stances on other issues (the country recently liberalized its alcohol consumption rules and, well, one of the headline events for the hotel’s opening was a celebration of a tequila brand; in addition, Beyoncé was clad in a revealing outfit for her performance). Beyoncé is especially vulnerable to this critique given that her latest album features homages to LGBT culture.

The artist of course is not the only major celebrity to benefit from the Gulf states’ largesse, whatever their political proclivities. Portuguese star Cristiano Ronaldo, approaching the end of his soccer career, signed a deal with Saudi club Al Nassr for a reported $75 million. His rival, Lionel Messi of Argentina, signed a deal reportedly worth $35 million to become Saudi Arabia’s tourism ambassador. Other celebrities who performed in or visited Saudi Arabia include Justin Bieber, Paris Hilton and Alicia Keys. English soccer star David Beckham is playing both sides of the Gulf aisle, inking a $20 million-a-year deal with the Saudis to also promote tourism, along with a reported absurd $270 million agreement with Qatar to promote its World Cup last winter as well as other activities.

The Qatar World Cup of course was the epicenter of condemnations by rights activists in the run-up to it and during the World Cup itself, where the criticism touched upon migrant rights and other human rights violations, and in particular on the issue of LGBT rights and the fact that being gay is illegal in the country, alongside restrictions on solidarity expressions like possessing or displaying a rainbow flag. The restrictions prompted some expressions of discontent by some Western players, though most opted not to cause any problems with the host country or subject themselves to draconian punishments by FIFA, the world soccer governing body.

In contrast to these celebrities who have lined their pockets with Gulf millions, the Lebanese singer Fairuz, who turned 87 recently, has refused to perform in Saudi Arabia. A report in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz reported that Fairuz had declined to perform in the kingdom, a claim that was verified by her daughter.

It’s not entirely clear why Fairuz decided to buck the trend of artists performing in Saudi Arabia (and the Gulf in general) in exchange for unholy amounts of money, a trend that rights activists had hoped would retreat in the aftermath of well-publicized crimes like the assassination of dissident writer Jamal Khashoggi. Fairuz has not performed a concert in years as she has advanced in age and has not spoken publicly about the refusal and the reasons behind it.

One thing that is clear is that the attempts at online shaming of celebrities who associate with Middle Eastern autocracies, at least insofar as music and sports are concerned (as opposed to taking stances of overt political solidarity), do not work. Qatar hosted the World Cup without incident (in fact it was by many accounts one of the most thrilling tournaments ever). Saudi Arabia and the UAE, as they continue to prove the adage that everyone (except perhaps Fairuz) has a price, continue to attract celebrities, influencers and icons as they transform internally and externally (for better or worse).

This raises questions about the viability and effectiveness of online outrage and activism, where most of the condemnation tends to live. It is of course commendable to stand for LGBT rights and the rights of migrants. But its ineffectiveness and weakness in effecting any sort of change in the behaviors of celebrities or the regimes they condemn makes one wonder if it is out of touch or at the very least that it needs to find other avenues of agitation.

It also points to the uncomfortable fact that the Middle East tends to get singled out for protests related to cultural events compared with other venues. Russia, for example, received a fraction of the attention heaped upon Qatar’s human rights record when hosting the 2018 World Cup despite being involved actively in bombing Syrian hospitals and civilians in the two-year run-up to the tournament as well as being similarly abusive toward LGBT individuals. American celebrities continue to perform in states with restrictive abortion laws.

There is of course, uncomfortably, a gulf between the actions of a genocidal dictator like Bashar al-Assad or South African apartheid and the actions of run-of-the-mill autocracies that spy on their populace or jail and murder dissidents.

How should the latter be treated, and how should they be isolated if the goal is to effect positive changes in their policies? Perhaps taking aim at cultural events that aim to sportswash or “music-wash” these violations is the right avenue. Perhaps not. Either way, it does not seem to be working.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.