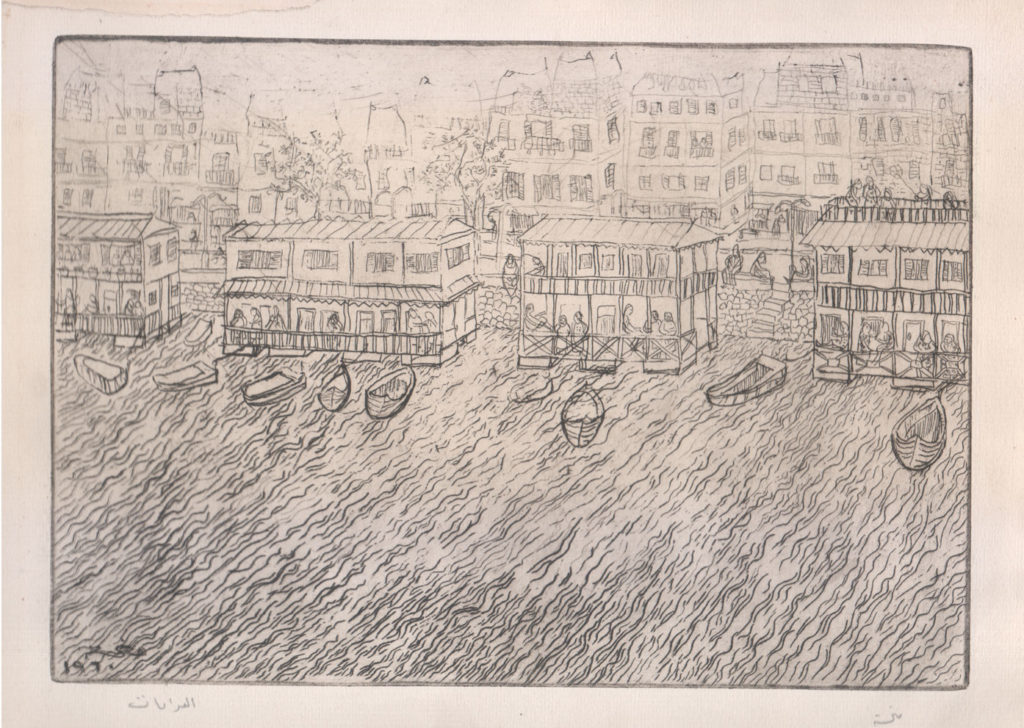

Against a backdrop of dilapidated, misshaped buildings lies a series of wooden houseboats moored along the shores of the Nile River. The two-story structures steady themselves with tranquil buoyancy, untroubled by the rippling river, while their occupants drift through open terraces overlooking the green banks, relishing simple joys uncommon in a city as chaotic as Cairo.

There is an outdated grace to these floating homes — an unlikely paradise besieged by a sprawling mass of concrete. They adorn the local landscape, hearkening back to a time before the dull-gray skyscrapers that flank the Nile’s western bank; a time when homes such as these were at the heart of a thriving Cairene culture, hosting late-night salons, intellectual debates and a refuge for society’s elite looking to escape the conservative capital.

This is the scene depicted in Menhat Helmy’s “The Houseboats” (1960), a charming black-and-white etching (a printmaking process that involves making art on metal plates using corrosive acid to cut into the surface) that offers a rare glimpse into life along the Nile more than six decades ago.

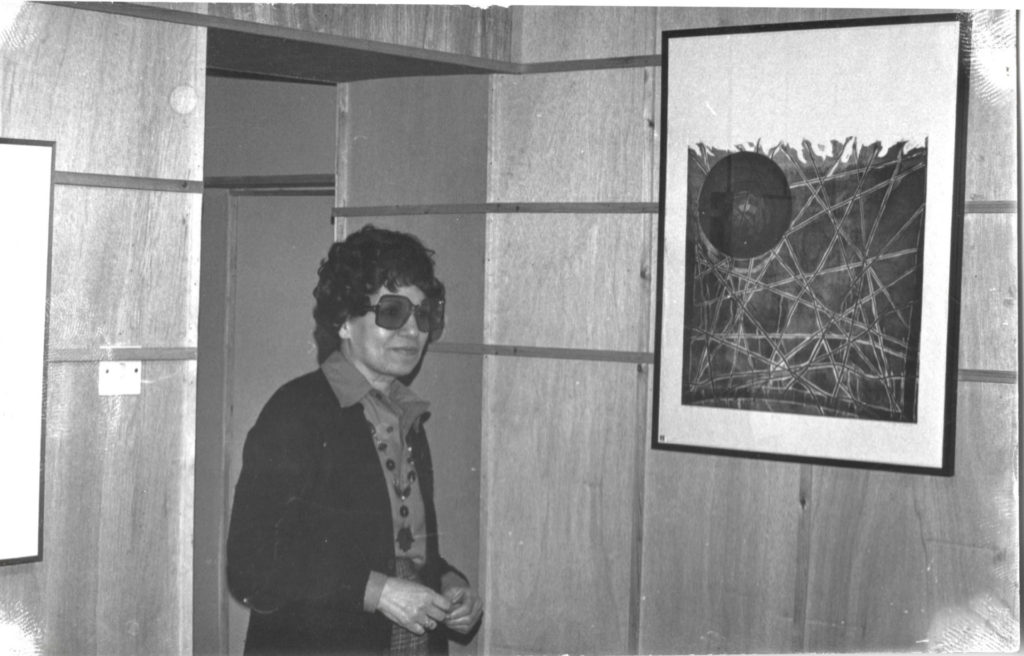

Helmy, who passed away in 2004 at age 78, was a pioneering printmaker and painter, and among the first Egyptian artists to create elaborate etchings that captured the intricacies and minutiae of life in Cairo during the unprecedented socioeconomic changes that transformed the country under former President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

She is also my grandmother, and I’ve only recently come to realize how significant her etchings are in a rapidly-changing Egypt.

In late June 2022, the Egyptian authorities began to forcibly evict residents and owners of the 32 houseboats docked along the Kit Kat area of Giza. The evictions followed a sudden decree from the Irrigation Ministry earlier that month, as part of a plan to develop the Nile Corniche and create a pathway for commercial projects along the river. By July 3, the entire Nile community had been evicted, leaving dozens of occupants — ranging from war veterans to writers to elderly women — stranded in the process.

The tragic incident marked the latest stage in the Egyptian government’s aggressive and expansive urban development drive — an unprecedented project that has resulted in the demolition of many of Egypt’s historic landmarks, green spaces and neighborhoods in its quest to become the new Dubai.

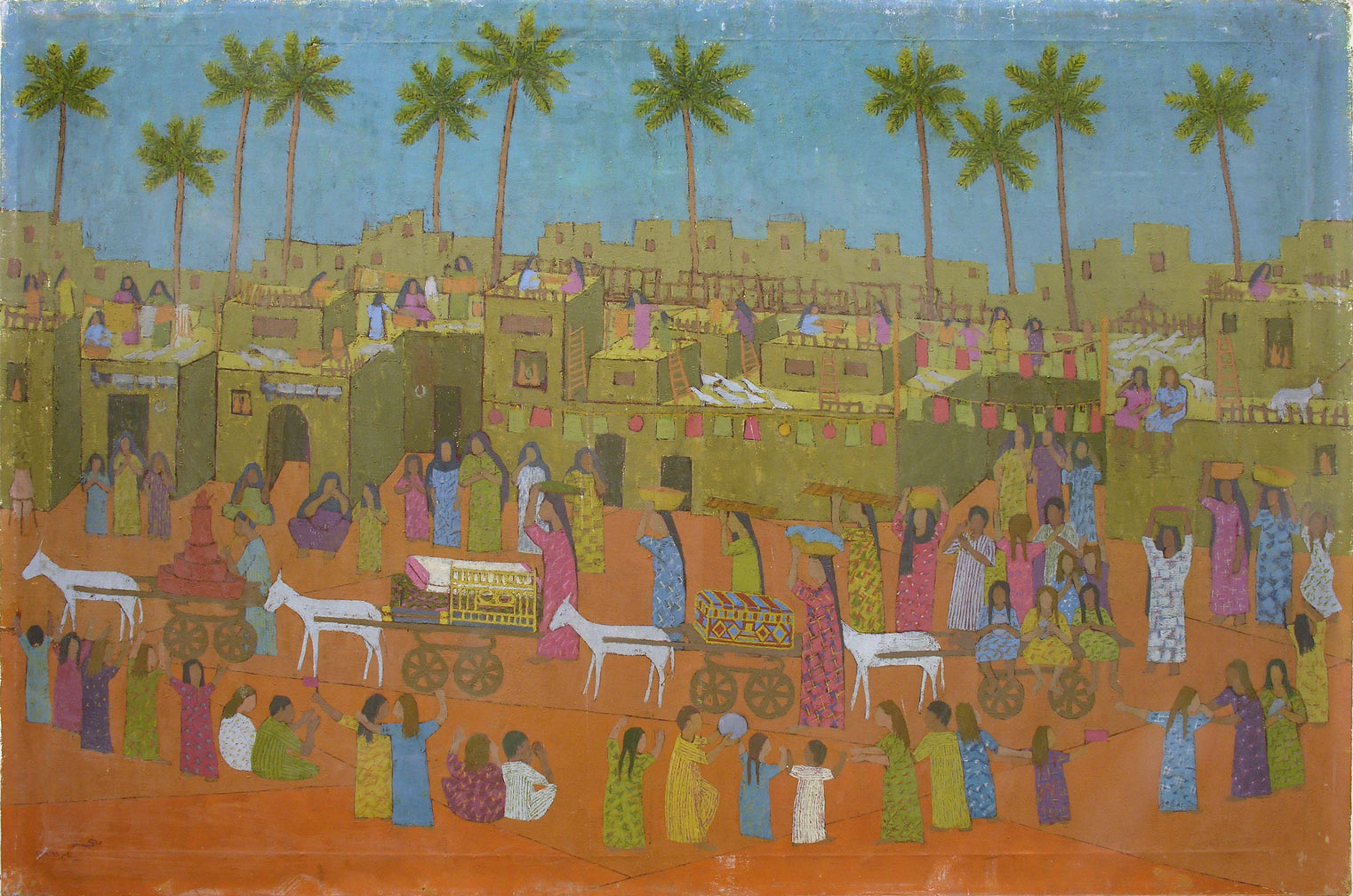

In consequence, my grandmother’s extensive oeuvre of etchings and paintings — scenes of lupin sellers, ancient mosques, popular theaters, agricultural fields and women at work in various settings — have transformed into a wealth of historical documents that capture the very essence of a bygone Cairo and its threatened identity.

At the close of his eighth year in power, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi continues to shape Egypt in his own image.

The military commander-turned-politician has overseen an endless stream of economic projects that prioritize profit at the expense of public interest, resulting in hundreds of thousands of Egyptians being forcibly evicted and displaced.

This was the case in the Maspero Triangle, a low-income neighborhood in the heart of Cairo that spent decades staving off the Egyptian government’s attempts to demolish and gentrify the Nile-adjacent area. After years of fighting and negotiating with various Egyptian administrations, more than 4,500 households were forcibly evicted in 2018 to make room for new developments.

Most residents of the working-class area were promised minuscule housing allowances from the government to offset a three-year redevelopment period, while the rest were offered alternative housing elsewhere in the city. Those who rented in these neighborhoods and had often inherited an extremely low rental rate from their parents or grandparents were given temporary housing or forced to immediately find new homes in a housing market they were largely priced out of. The new homes that have since replaced the shabby low-rise buildings are among the most valuable in central Cairo.

This unabashed gentrification agenda was used as a blueprint for several other informal neighborhoods demolished under the pretext of development. In January 2022, the authorities evacuated residents from the working-class al-Jayara, Hosh al-Ghajar, al-Sukar and al-Lemon neighborhoods in Old Cairo in order to develop new tourism and entertainment projects spanning 12.5 acres. Later that month, hundreds of thousands of residents of the 6th and 7th districts of the Nasr City neighborhood, a planned district in eastern Cairo built in the 1960s, were forcibly evicted to make way for luxury housing developments.

In August this year, protests erupted on Warraq Island, an islet in the Giza Governorate, over government plans to forcibly evict its approximately 100,000 residents to make room for a luxury district dubbed Horus City.

“These pictures are not of Manhattan, USA! Can you believe they are actually the designs for Egypt’s Horus City, previously Warraq?” asked Egypt’s State Information Service on Facebook, alongside pictures of the futuristic digital models proposed for the city, which the government noted will include “seven-star hotels.”

While the Egyptian government defended its actions by labeling the targeted neighborhoods as “slums” and deeming the buildings unsafe or unsuitable for living in, critics have accused the authorities of monetizing the land by selling it to wealthy investors looking to create commercial ventures.

Other detractors raised concerns about the replacement housing projects that have been erected to house residents from Cairo’s demolished settlements. Among these is the Asmarat housing project in Cairo’s hilly suburb of Mokattam, which houses more than 10,000 relocated families, including many from the Maspero Triangle. These areas are somewhat isolated, meaning there are limited services and resources such as schools, hospitals, markets and public transportation available to residents. In one research paper, an Asmarat resident likened the experience of living there to being in an “open-air prison.”

The crown jewel of el-Sisi’s mega-urbanization drive is the New Administrative Capital, a city with an estimated budget of $58 billion that is the most expensive project undertaken by the current regime. Located approximately 30 miles east of Cairo, construction began in 2015 and is expected to conclude in the coming years. Government departments and civil servants will be obliged to permanently relocate from Cairo to the new city upon its completion. The New Administrative Capital will span over 270 square miles — roughly the size of the Kingdom of Bahrain in the Persian Gulf.

Planning for the New Administrative Capital included investment in transportation infrastructure such as bridges and expressways, which have contributed to the destruction of some of Cairo’s green spaces and heritage sites.

In 2020, the authorities demolished rows of graves and mausoleums in Cairo’s historic City of the Dead to carve out space for a new multilane highway. The demolition sent shockwaves throughout the country, as the series of ancient cemeteries housed many of the country’s famous rulers and intellectuals, as well as ordinary citizens. It was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979.

Among the more recent tombs to face demolition was the resting place of Egypt’s literary giant Taha Hussein, which was reportedly earmarked for removal to make way for an overpass and corridor connecting a web of new bridges. Following scathing criticism from some of the country’s most notable cultural figures, the authorities denied having plans to demolish the tomb.

Egypt’s green spaces have also suffered the wrath of Cairo’s unsettling transformation. Heliopolis, an affluent district that once housed the residence of former President Hosni Mubarak, lost more than 100 acres of green space (roughly the size of 70 soccer pitches) since 2019 to make way for new streets, overpasses and state-owned gas stations. Several other locations, including Ahmed Fakhry Street in Nasr City and 17th Street in Mokattam have also seen their green lungs razed, leaving behind yet another irreversible tear in Cairo’s urban fabric.

During my most recent trip to Cairo in the summer of 2022, I was distraught over the unabashed destruction and reconstruction of this ancient city and its cultural hearts. I turned to my grandmother’s work to revisit her Cairo, unmarred by such unchecked development.

Yet in reviewing her works, I realized my Cairo was not so different from hers.

Born in 1925 and raised in Helwan, a once-peaceful suburb on the Nile bank that stands opposite the ruins of Memphis, my grandmother grew up in a neighborhood filled with lush gardens, wide streets and estates that housed large families with many children. She herself was the middle child among seven sisters and two brothers, which may explain why she was driven to distinguish herself through artistic expression. Encouraged to pursue art by her supportive parents, Helmy dedicated herself to her craft and graduated with distinction from Cairo’s High Institute of Pedagogic Studies for Art in 1948, before receiving a teacher’s diploma the following year.

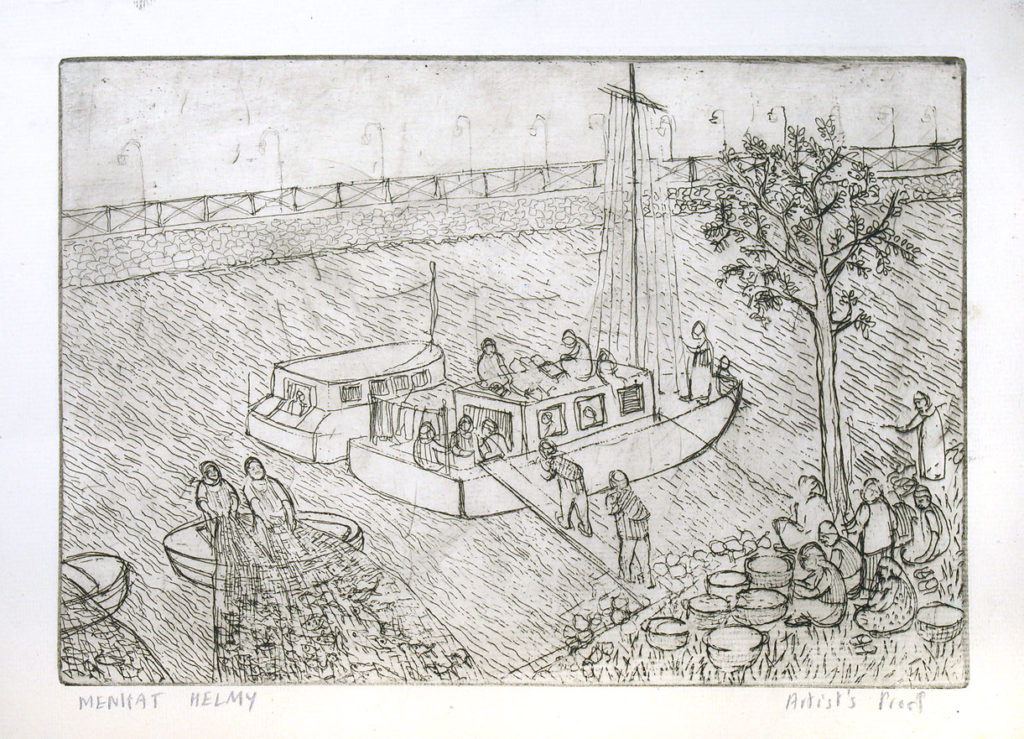

Helmy’s noticeable talent earned her a government scholarship in 1952 — just months after the July military coup that overthrew Egypt’s monarchy — to continue her education in London, England, at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art. It was there that she discovered printmaking and began to experiment with different plates and techniques. Eventually, she settled on etchings as her preferred medium.

Helmy traveled across England during her three years at Slade, exploring parks, churches and rivers and carrying a small sketchbook that she used to lay the foundations for future prints. She captured the country’s diverse landscapes and immersive gardens, occasionally portraying figures reading newspapers or going about their day. Her work did not go unnoticed: She was awarded a prestigious etching prize in her final year at the university.

Returning to Egypt in 1955, Helmy found her country consumed by socioeconomic upheaval and nationalistic fervor. Under Nasser’s rule, Egypt introduced far-reaching land reforms, as well as a series of socialist measures aimed at modernizing Egypt. Thrust into a rapidly-changing Cairo, Helmy began to feverishly document the societal changes taking place around her, capturing historic events such as the Suez Canal crisis, the construction of the Aswan High Dam and the 1957 parliamentary elections, which marked the first election in which women had the right to vote or stand for election in Egypt.

It was during my grandmother’s resettlement in Cairo that Nasser announced plans to turn her native Helwan into a major industrial city. Throughout the late 1950s, Helmy witnessed her quaint neighborhood first transform into automobile factories and a massive steelworks zone and then develop into a run-down suburb, unrecognizable to its residents. Her parents and unmarried siblings relocated to the affluent suburb of Maadi in 1961. The sudden erasure of Helwan’s cultural heritage and historic neighborhood left a profound impression on the young artist.

Helmy had a flair for capturing Cairo’s fleeting grace, from its once-proud agricultural fields and its shimmering Nile shore to its popular theaters, marketplaces and water-docked casinos. Each etching bore her trademark eye for precision and her sensitive nature, inviting viewers to bear witness to the lives of regular Egyptians.

In “Lupin Seller” (1956), Helmy re-created a scene typical of any of old Cairo’s many informal neighborhoods. There is a man selling pickled lupin beans, a snack popular in Egypt and other Mediterranean countries; women balancing jugs on their heads waiting to fill them from state-established water fountains; children playing in a nearby school or helping their fathers sell goods across the street; and donkeys carting bread and other goods to a nearby destination. Helmy assumes a bird’s-eye perspective in her etching, allowing us to watch over the various figures as they go about their day with grace and dignity, seemingly unperturbed by the changes taking place around them. While the work is set in central Cairo, it is very likely that Helmy grew up surrounded by similar scenes in Helwan.

Helmy would maintain this panoramic perspective in many of her etchings in the 1950s and 1960s, including “Outpatient Clinic” (1958), which portrays rows of women breastfeeding their children in an enclosed, outdoor space in old Cairo. The etching, which was later rendered as a painting that is now part of the Barjeel Art Foundation collection in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, was one of the earliest examples of an Egyptian artist depicting breastfeeding in conservative Egypt.

Another etching from the same year — “In the Village” — takes viewers onto a multistory rooftop in old Cairo, where women take part in activities such as kneading dough, washing clothes, raising chickens and chatting with their neighbors while dangling their legs off the edge of the roof. It is a realistic depiction of life in one of Cairo’s informal neighborhoods, many of which have now been eliminated.

While Helmy depicted many spaces within the city, one neighborhood in particular would steal her heart and go on to become an important part of her storied legacy.

In 1965, an Egyptian women’s magazine published an article about Helmy titled “Bulaq wins an Honorary Prize in Yugoslavia,” celebrating the artist’s repeated successes and prize-winning participation at the Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts.

Helmy had won consecutive honors at the prestigious biannual exhibition in 1961 and 1963 for her etchings documenting life in Bulaq, a Nile-front district in the northwest of Cairo and the surrounding area. Bulaq was among Cairo’s oldest quarters, filled with run-down buildings, energetic markets and a predominantly working-class population.

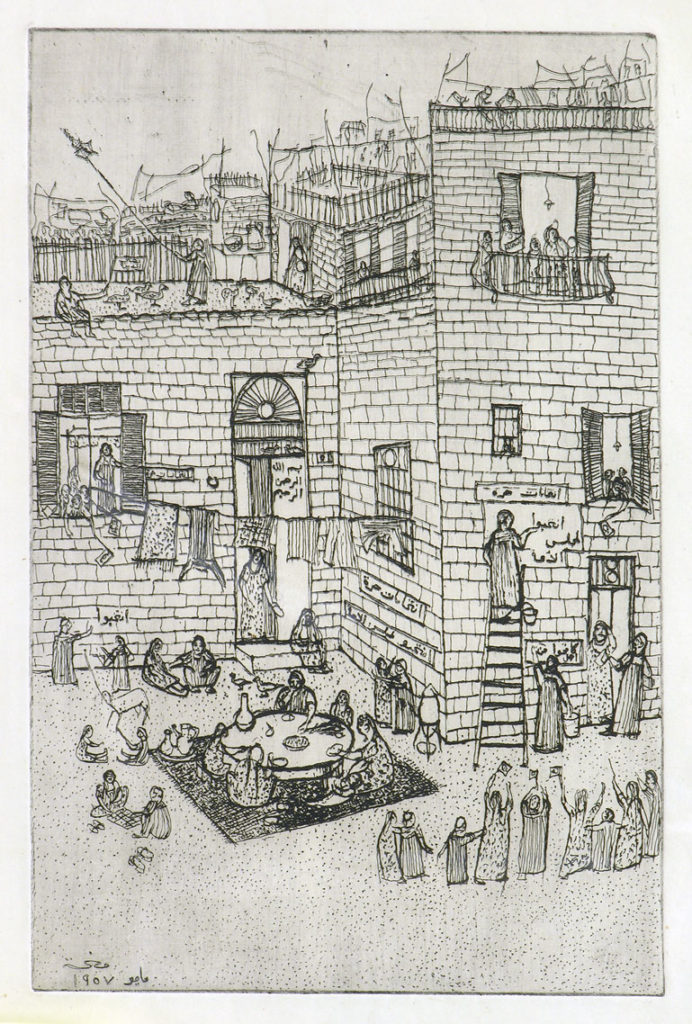

The magazine article featured several of Helmy’s works, including a small reproduction of an etching from 1957 titled “Ezbet el-Ward,” an informal neighborhood that was demolished as part of Nasser’s attempt to modernize Cairo. It is a tightly-constructed composition showing a dense mass of busy streets and crumbling buildings filled with laborers dressed in galabiyas (traditional robes), children playing soccer and donkeys pulling carts filled with fruits and vegetables. The figures are small yet full of life, as though waiting for viewers to turn their heads away so they can continue about their day.

In the caption, the magazine referred to the etching as an “old picture from a bygone era,” as it portrayed the section of the neighborhood that would later be torn down for redevelopment. This marked the earliest example of Helmy’s work being recognized for its historical value.

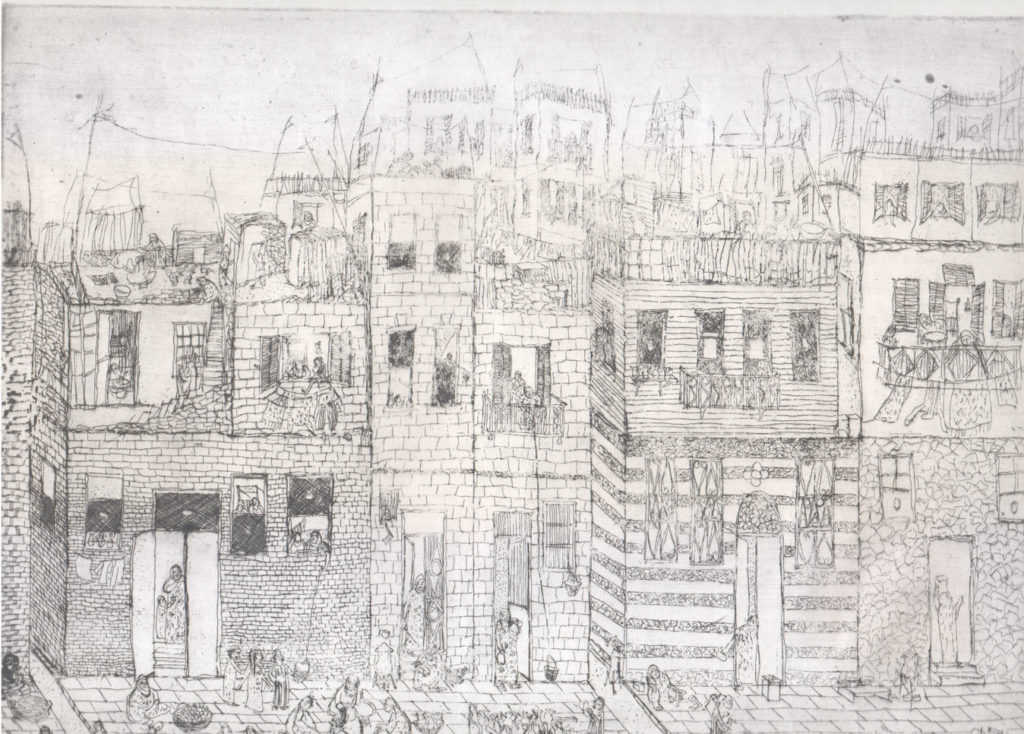

Bulaq continued to undergo a significant transformation throughout the 1950s and 1960s, as newly erected buildings and factories eclipsed life in the beloved district — life that was captured in Helmy’s award-winning “Bulaq in the Morning” (1957). The etching portrays a single, densely-packed row of apartment buildings bursting with life and old-world delight. Figures spill out of every window, staring back at the viewer. Neighbors chat across balconies while hanging clothes and launching rope baskets down to the street below. Children play in the alley while young mothers watch over them from the sidewalk. Street vendors sell sweets and bread. Every figure is endowed with a sense of self and identity.

“Helmy fills the black and white print with textures, rich patterns, and strong graphic details,” wrote the art historian Bojana Videkanic in his book “Nonaligned Modernism: Socialist Postcolonial Aesthetics in Yugoslavia, 1945–1985,” which featured several of Helmy’s works, including “Bulaq in the Morning.” “The work is bursting with energy, offering an almost documentary-style slice of life.”

Helmy went on to create more than a dozen etchings focused on life in Bulaq and its environs. Some were dedicated to specific traditional celebrations typical in informal neighborhoods such as the Mawlid (commemoration of the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday), including the once-popular sugar dolls given to children on that occasion. While the prophet’s birthday continues to be celebrated throughout Egypt, the traditional festivals and sweets that once marked the happy occasion are distant memories.

When asked in a 1966 interview about her decision to feature Bulaq so heavily in her work, Helmy revealed that, despite being among the few privileged artists who traveled and studied abroad, Bulaq was the area that most resonated with her.

“Nothing has as much of an effect on me like working-class neighborhoods do,” Helmy said at the time.

While Helmy would ultimately pivot to abstraction in the 1970s, the artist’s chronicling of Bulaq and other informal neighborhoods in central Cairo throughout the 1950s and 1960s remains remarkably relevant all these decades later.

In Helmy’s time, the neighborhoods of Bulaq and Helwan were particularly targeted in the race toward modernity, leading to the slow decay of Cairo’s old districts and the wealth of culture and traditions within them. The current regime has followed Nasser’s path, forcibly evicting working-class residents, razing their homes and neighborhoods and replacing them with infrastructure and services aimed at a wealthier clientele. El-Sisi’s mega-urbanization projects have effectively erased Cairo’s remaining charm and character, all in the name of characterless vanity projects such as the New Administrative Capital, aimed to define his tenure in office and establish a legacy that will live beyond his own mortality.

By documenting Cairo’s unseen majority and representing everyday life in elaborate etchings, Helmy was able to preserve a portion of the city’s urban fabric prior to its imminent destruction. While my grandmother could not have known just how much her beloved city would suffer at the hands of its ambitious leaders or how similar our plights would be despite the generational gaps, her work serves as a snapshot of better times — a bygone age when Egypt’s sprawling capital was defined by its people, not its monuments.