Abdulaziz Alhosni, clad in a dishdasha (a long robe traditionally worn by men in the Gulf), is submerged in water and making piercing eye contact with the camera. It is a moody self-portrait that’s open to interpretation in any number of ways. There is neither caption nor context — and most of his more than 27,000 Instagram followers don’t seem to care.

The comments section on his feed sees comparisons between Alhosni and Freddie Mercury, in response to his vintage-inspired stylistic approach, which layers grainy textures over evocative styling. “Your ideas are unique and strange, and that’s what makes your account great,” reads one comment. A conversation with this young photographer, however, reveals the unseen side of challenging social norms in Oman, at the eastern edge of the Arabian Peninsula.

The “rigid rules of masculinity,” he says, don’t make sense to him. Alhosni’s personal convictions shape his creative identity as a conceptual photographer, and he divides opinion as a silent advocate for young men embracing vulnerability. “Creating major change may be forbidden, but small shifts can arise from art,” he says. “This way, the next generation will be able to share their emotions and show more of their true selves.”

It’s a mission that comes with backlash.

“The people who are offended by my art don’t visit galleries or exhibitions — they’re simply not interested,” he says. “But people have been a lot more active on social media since the pandemic. It’s generally older people who are more resistant to change, technology, colors even. They don’t like the idea of someone trying to change their culture.” The 23-year-old persists, inevitably taking on the role of youth ambassador by addressing the social issues — particularly the intersection of youth and love — that impact his peers.

His “Habayeb Club” series, for example, creates an imaginary space for people who are hesitant to express their feelings, and features the photographer sporting a pink kummah hat embroidered with hearts in one of its visuals. As in the rest of the Arab world, love is an emotion that is rarely expressed outwardly in Oman. For “Magic Land,” meanwhile, Alhosni looked to Michelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam” for inspiration. Set in ancient Egypt, he depicts himself as a young Omani man befriending a local boy who has harnessed the power of a magical love potion.

Mohammed Alattar is another artist defying gender norms with his work, which he refers to as a “safe space” for introspection. Refusing to be restricted by tools and mediums, he has experimented with gouache, acrylics, watercolors, mixed media, dry ink pens, digital art and even performance art — with one common denominator. Having grown up struggling with fears and insecurities, Alattar is vocal about his own journey dealing with toxic masculinity and turning to art in order to create “an open space free of judgment toward broken souls.”

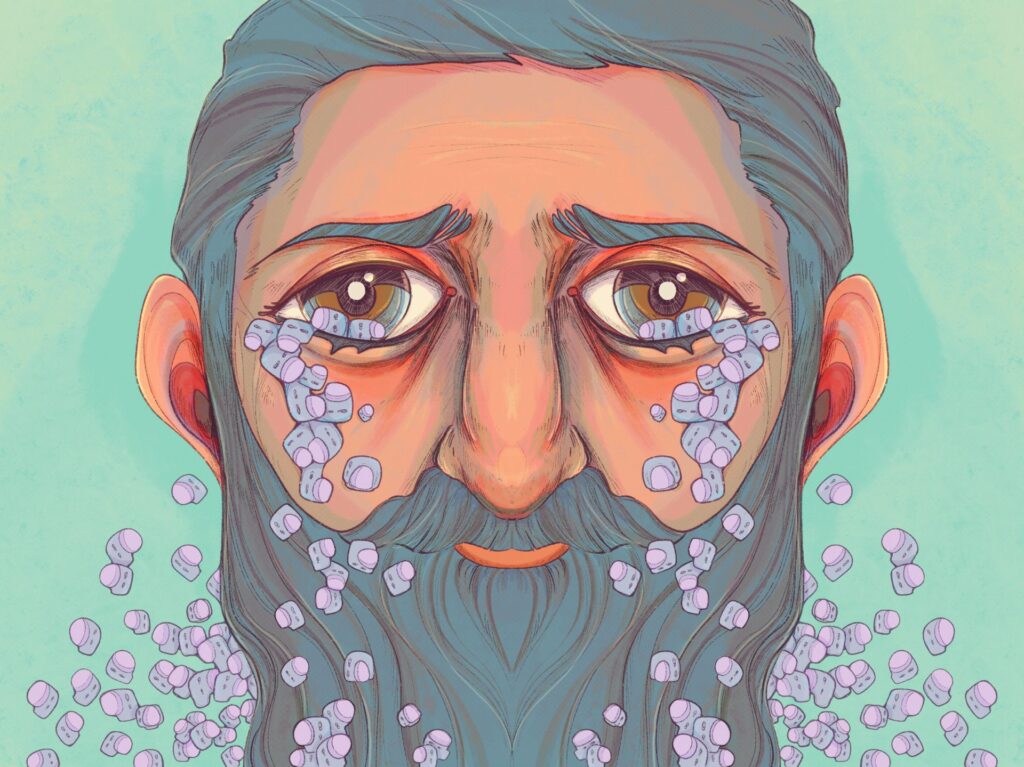

The result is a portfolio of intricately detailed and highly emotive works that explore a universal human experience — feelings of vulnerability — through the lens of a young Omani man. Tears are a recurring motif, taking on unexpected forms, like expressive thoughts in “Spoken Thoughts Tears” and streams of blood in “Bleeding,” both portraying a pensive, bearded subject — much like Alattar himself.

“I share my personal struggles, as I’m well aware that we feel less alone when we know someone out there shares our pain, and that itself brings us comfort,” he says of his stand against the social constructs of masculinity. “There are restrictions when it comes to art, but I feel a sense of responsibility to address matters that don’t get enough attention as they’re too sensitive for a very masculine-driven community. Art is a tool for silenced voices to be heard without suffocation. Generations of compress, compress and compress have led to one that’s untangling itself from the idea that conveying emotions is feminine. But it’s not feminine nor masculine. It’s human.”

Alhosni and Alattar are part of a new wave of young artists who are unapologetically doing things differently than their predecessors, their work replacing the oil paintings of yesteryear, when depictions of mountains, mosques and historical structures like forts pervaded. Anwar Sonya is one such predecessor. Dubbed “one of the founders of the Omani Art Movement” by the Muscat-based Stal Gallery, the septuagenarian’s impressionist style centers around the topography and heritage of Oman. The Bedouin women of Dhofar, the region he calls home, also inspire his paintings.

Still, with the sultanate rarely in the global spotlight, its art scene also takes a back seat to those of its neighbors. The wealthy state of Qatar has famously invested billions of dollars into culture and tourism, one of many efforts to reduce its reliance on the energy industry. “We have a grand ambition, one that we will deliver together, as a group of museums and sites to help fulfill the cultural goals of the 2030 National Vision,” says Sheikha Al Mayassa, chairperson of Qatar Museums. The pioneering Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, for example, was established in 2010 (the same year that Qatar won the bid to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup), signaling the country’s development plans to the world. And now that the World Cup is done and dusted, the Qatar Auto Museum and Dadu, Children’s Museum of Qatar are expected to launch in the coming years.

Nearby, Saudi Arabia’s rapidly growing art movement symbolizes the kingdom’s metamorphosis from a land where cinemas were banned for 35 years to a regional hub of culture and entertainment. The country registered on the radars of art experts when da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” sold for a record-setting $450 million by proxy to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in 2017. Contemporary art and futuristic elements dominate this country’s artistic stage, with leading patron Basma Al Sulaiman inviting the world to create an avatar and view her private collection at the virtual museum BASMOCA. The UAE, meanwhile, continues to pioneer the region’s embrace of creativity — Louvre Abu Dhabi’s 2017 debut marked the arrival of the first universal museum in the Arab world, while Dubai hosted its first digital art festival earlier this year.

In contrast to Alhosni and Alattar, the visual artist Eman Ali prefers to leave gender out of the discourse, despite acknowledging that the art world is male-dominated.

“This is also true in the Gulf region, which hits closer to home for me,” she says. “Still, I prefer to be viewed simply as an artist, without the need to emphasize my gender. The world tends to put people in boxes, and it’s crucial for me to break free from those constraints. But my perspective becomes vital in such a male-dominated industry. It acts as a disruptor, challenging the status quo and offering a different narrative.”

Dividing her time among Oman, Bahrain and the U.K., Ali uses her practice as a means of social critique and investigation into the layered histories of East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Religious and sociopolitical ideologies in Arab societies are often woven into her work, as is gender — the stigma attached to the female form, to be exact. In her boundary-pushing installation, “Her Holeyness,” simple everyday objects are employed to communicate themes like cleanliness and purification, reflecting views in a region where female virginity is still highly prized and the commercial representation of femininity borders on comical. Showcased as part of the Royal College of Art Graduate Show in London, it saw the absurdity of products like artificial hymen pills — which promise to “revirginize” a woman — take center stage in a dark, glossy setting that incorporated sound, photography and light.

Within a more serious conceptual framework, Ali manages to playfully imply that, in the Middle East, the female body is a mere commodity that must be continually maintained. “If I were to show this back home, how would I do it in a way where I wouldn’t be censored or get into trouble? The concept behind the work speaks to a very prevalent social and cultural issue,” she explains. “I quite often include a lot of symbolism in my images to subvert their conventional meaning, which leaves my work open to interpretation. In this case, I’ve made the series ambiguous enough to navigate through potential obstacles, allowing it to be appreciated as still life, even if you don’t know the underlying story.” The secret, she says, lies in the captions. “They’re the keys to unlock the work. Constraints can be a good thing as they force you to think more creatively about how you want to communicate an idea. I see them as a means to empower my work rather than restrict it.”

If “Her Holeyness” were to go on display in Oman, she says, then certain officials would come in to pre-screen the work before its opening. “I could get away with showing these images because they aren’t so explicit. The captions, for me, were really important in this body of work because that’s the key to unlock the images.” Interestingly, the Barbie-pink soap starring in “Eman Virginity Soap” isn’t named after the artist; eman means “faith.” More recently, she took a monthlong journey across her native Oman that resulted in a collection of 100 images, titled “The Earth Would Die If the Sun Stopped Kissing Her.”

A contemplative examination of the sultanate, the series encapsulates the everyday relationship between nature and humanity, with Ali capturing both shadowed moments indoors and the vast, untouched landscapes outside. One photo, set amid the towering Bousher sand dunes of Muscat, has garnered more attention than the others. It highlights the hijabi pole-fitness instructor Nusaiba Al Maskari, her outstretched body perfectly aligned with the rugged Hajar Mountains in the background.

“It’s not about being superior or inferior to male artists, but the importance of representation,” she continues. “By showcasing our art and sharing our experiences, we break down barriers and create a space for more diverse voices to be heard. Our lens offers a unique vantage point, one that enriches the artistic dialogue and challenges the established norms. It contributes to the ongoing conversation, encourages inclusivity, and inspires others to embrace their own authentic voices — regardless of gender or societal expectations.”

Gender isn’t the most recurring theme in Oman’s peer-led art scene; identity is. Customs, cultural norms and a deep-seated connection with the country’s scenic landscapes repeatedly influence the work of young creatives. One can’t help but ask: Is it a response to the modernity that’s inevitably creeping in? Or are young Omanis simply more in touch with their roots than some of their counterparts throughout the Gulf Cooperation Council countries?

The answer is nationalism. “The ideology is instilled early in life. In fact, there’s an academic curriculum dedicated to it, and it’s part of what builds an appreciation towards our culture,” says the artist and filmmaker Mahmood Al Zadjali.

The self-professed liberal has been known to incorporate Oman’s traditional attire into his work, but has been criticized in the past for his own clothing choices. “People have accused me of lacking ‘aadat wa taqaaleed’ (customs and traditions) because I frequently wear what is considered Western clothing. And then there are artists who take pride in the culture while spinning it in a way that works for them. Look at Alhosni. He has featured Yeezys in his artwork. Having a rich culture doesn’t mean we pretend the West doesn’t exist.”

A glance at Al Zadjali’s past works reveals that he isn’t afraid to view Omani values through a critical lens.

“Considering Arabs from the Gulf were once Bedouins, belonging to something is extremely important. We’re a community-based society. We huddle back to our tribes whenever we’re sad or happy,” he explains. “On the other hand, tribalism can be dangerous if used in the wrong context, with the younger generation usually paying the price of social pressures.” Referring to his “At What Cost” photography series, he talks of the financial pressure that comes with hosting lavish weddings. Most Omani youth struggle with the pressure, he says.

Getting married is an expensive affair in the sultanate, with young grooms traditionally taking on both wedding expenses and dowries, and therefore resorting to taking loans. Worse still, higher dowries are considered a source of pride and can be set as high as 30,000 Omani rials ($77,000) in some regions. Simultaneously, youth unemployment stood at 49% in 2019, according to the World Bank, a situation only worsened by the pandemic. In a rare display of discontent, young Omanis — triggered by the introduction of value-added tax in 2021 — took to the streets of Sohar and Salalah to protest poor economic conditions.

Issues of identity troubled Al Zadjali yet again when the UAE-based independent collective Swalif approached him to participate in “Encapsulated Volume 1: Photoessays on Khaleejiness.” The book is intended to serve as a meeting point for ideas and cultural impressions of what the Khaleeji, or Gulf, experience entails for the younger generation, through artworks by aspiring and emerging creatives. The artist confesses that he initially questioned his place within its pages. “I kept asking myself, ‘Why do I consider myself Omani as opposed to Khaleeji?’ I think a lot of it stems from my mother’s side, which is from the Balushi family. And it always felt like my ‘Balushi-ness’ created this umbrella of sorts. We weren’t isolated from the outside world, but we have our own lingo, food and folklore. I don’t need another identity, you know?”

The book inspired Al Zadjali to work on a portrait series of young women wearing Balushi outfits handmade by his mother, each contrasted with Vans sneakers or pop art accessories. The Balushi tribe traces its origins to Balochistan, a region split between three countries — Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan — adding another facet to the complex Omani identity. Oman is home to an estimated 57 tribes, although some claim the number exceeds 200. Omanis are ethnically diverse, too. While the majority of the population is Arab, there are also locals of Swahili, Lawati, Lurs, Mehri and Persian origin, owing to historic factors like slavery and trade routes.

Alattar, meanwhile, points to Oman’s art history to account for the fixation on identity. “We’re very attached to our origins, so growing into a community without realizing it will influence you. The artists who stepped outside the box in terms of what they expressed through art were not celebrated as much as those whose work was rooted in cultural aspects.” From his perspective, a disconnect in the Omani art scene leaves much to be desired. “It’s highly divided,” he explains. “There’s no link between the elder, the current and the upcoming generations — the current community is filled with small lobbies, and their lack of confidence leads to them playing god in choosing whom they approve and don’t approve of, creating a very toxic environment for creatives. On the other hand, there are different art movements that are fair and welcoming of all talents, and we have high hopes in them.”

Elsewhere, a long-standing attachment to traditional art creates resistance to the narratives of new generations, he says. “Despite all this, we have self-driven and super-skilled artists who are working hard to put themselves out there, never depending on internal support from the country.” Novel mediums like digital art, which Alattar often uses, are sometimes dismissed or even feared in Oman — in stark contrast to Saudi Arabia, where the world’s first educational art center dedicated to digital art is imminent. Like Ali, he has had to exhibit his works abroad, but the recent opening of the Oman Across Ages Museum in the old capital city of Manah offers hope.

A brainchild of Qaboos, this new cultural landmark tells stories of Oman’s rich heritage and modern achievements by way of interactive, high-tech exhibits in a geometric, steel-clad setting inspired by the Hajar Mountains. The permanent exhibition alone spans about 100,000 square feet and over 800 million years of history.

“Two of my digital works were on display, but we still don’t have a proper space where we can showcase our digital art without them being printed,” Alattar reveals. “It makes no sense for a newcomer to bring their own screens every time they want to exhibit. Things are slowly getting better, but it will take time. That’s why I wouldn’t recommend creatives to wait for us to get there; they can always build their portfolios and take them where their talent will be appreciated.”

Ali echoes his sentiments, saying that Oman has fallen short in nurturing untapped talent. “In the past, we had to look beyond the Gulf region for recognition of our creative endeavors. However, Arab communities are now seeking and celebrating homegrown talent. It’s a beautiful transformation to witness. Unfortunately, Oman has not reached that stage yet. And what’s increasingly frustrating is that individuals in a position of power, who can be catalysts for change, often lack an understanding of the art field and show little faith in local artists, leading to overlooked talent and limited progress. This hampers the growth of artists and forces many — including myself — to seek opportunities outside.”

Describing the working environment as stagnant, she adds that artists are taking matters into their own hands, seeking opportunities to exhibit their work in unique and unconventional ways. Alhosni comes to mind. Without a camera to his name, he’s one of many young Omani photographers who are using their cellphones as a contemporary art medium and their social media accounts as galleries, patiently showcasing their works until a more sizable shift occurs.

“I deeply admire their determination and resourcefulness because, in reality, there is insufficient support from private institutions and the government,” Ali says. “Instead of waiting for assistance, the community embraces a DIY punk ethos, forging their own path forward.”

Progress, however slow, is not to be ignored. Oman presented its inaugural national pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale last year, offering a glimpse of the country’s cultural ambitions. Titled “Destined Imaginaries,” it displayed the works of three generations of contemporary artists, each responding to a question raised by artistic director Cecilia Alemani: “What would life look like without us?” The result was a series of installations that reflected on past, present and future, many of which inevitably touched upon national identity.

The multimedia artist Hassan Meer, for example, harkened back to the 1960s and ’70s in “Reflection From Memories.” Pairing found objects like personal letters and marriage chests from houses in the old town of Muttrah with a photographic slideshow and short films playing on screens embedded within old suitcases, it delved into the very specific period of modernization that followed the discovery of oil and saw many in the Omani diaspora move back.

“What I’m increasingly noticing is the level of diversity in Oman’s creative landscape,” Al Zadjali says. “Pre-2010, art was essentially defined as somebody holding a paintbrush. A bubble has burst since then.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.