After the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, Iraqi writers cultivated a particular strain of experimental literature that pushed beyond the boundaries of realism, dipped into the dark recesses of the traumatized psyche and explored the supernatural, the absurd and the grotesque. In doing so, they have simultaneously continued a century-old literary tradition entwined with tumult, beginning with portrayals of Iraqi revolts against the British occupation, and departed from Baath-era writers who for decades either put literature in service of the state’s powerful propaganda mill or wrote opaquely to avoid censorship and repression.

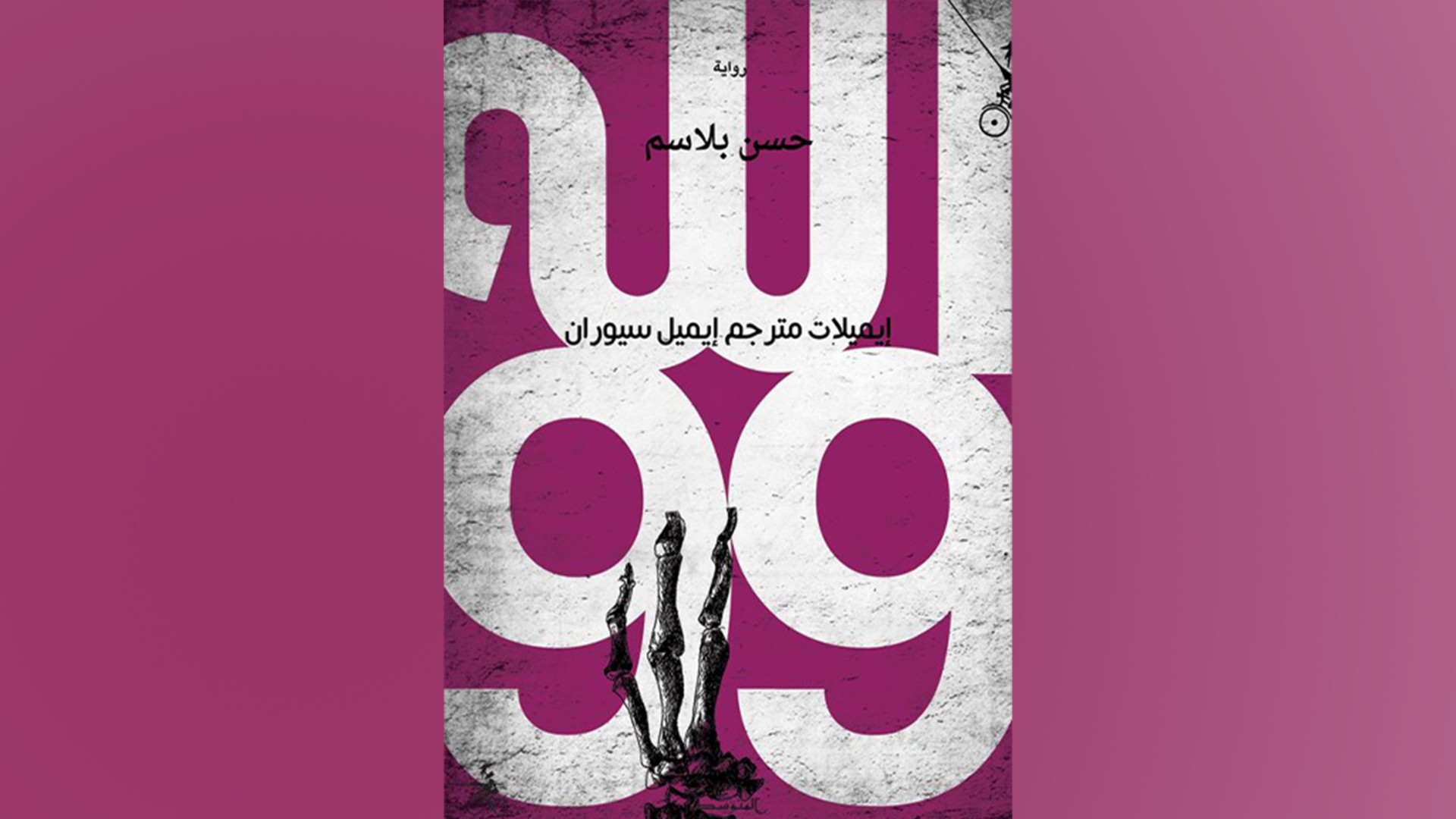

In this paradigm-shifting, post-invasion context, Hassan Blasim — author of “The Corpse Exhibition,” a collection of short stories, and editor of “Iraq + 100,” a sci-fi/magic realism anthology — has released his first novel: “God 99.” Drawing on diverse literary styles, Blasim tells a tortuous, mosaic, imaginative and most unconventional story.

“I was watching a report about the discovery of a new mass grave in Iraq when I had the idea of starting a blog and publishing my short stories and poems as a way of circumventing Arab censorship,” writes Hassan Owl, a narrator whose first name and life story bear a deliberate resemblance to Blasim’s own experience as an Iraqi refugee and writer in Finland. Through the frame story of Owl gathering stories for the blog, Blasim weaves together the otherwise varied narratives that compose “God 99” (a reference to the Islamic tradition that says God bears 99 names). Blasim also stitches these stories in with emails from another character, Alia Mardan, to Owl. Inspired by Blasim’s friend and Iraqi writer Adnan al-Mubarak, Mardan is translating the Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran as she corresponds with Owl — sharing her progress, details of her ailing health, and musings on life and literature. Blasim creates “a large collection of fragments” — a phrase used by Mardan to describe one of Cioran’s works but also a likely allusion to Owl’s own — of the humorous, absurd and sickening.

Taking readers on a disorienting journey while blending reality with fiction, Blasim has a knack for wit, morbid irony and deep reflection. In the comically dark story of Owl’s own birth, for instance, a nurse places Owl in an empty egg box and his uncle comes to collect him and his mother from the hospital in a garbage truck emblazoned with the phrase “Keep Your City Clean.” In a more pleasant story, “YouTube Man and the Flies,” a thief breaks into the house of an elderly, paralyzed woman and ends up cooking lentil soup for her. Blasim also blends fiction with further fiction through intertextual references like those to postmodern Italian writer Italo Calvino, who, with his use of the second person, the frame story and metatextual elements, serves as clear inspiration to the author.

Relating even the most horrific traumas with a dispassionate voice, Blasim underscores the bleak ordinariness of violence in the Iraqi and refugee experience. He features a great deal of dismemberment and disfiguration — part and parcel of the dark snippets of life, which Blasim (re)produces on his pages — in “God 99.” Daesh (the Arabic acronym for the Islamic State group or ISIS) decapitates people, rendering them into body fragments. Car bombs mutilate faces; a funerary mask-maker must then restore them. A playwright’s eyes are “torn to shreds” by American bullets. Owl’s own fingers are severed. Characters also suffer through the dismemberment of their identity and integrity. “Refugees whose lives have been destroyed by violence and fear have to live every day in their new homes as suspects, with the charges against them listed on a sign on their chests — Fugitive From Your War, Rapist, New Invader, Barbarian, Terrorist, Retard, Thief of Your Womenfolk, Thief of Your Taxes, Distorter of Culture,” Owl says to fellow refugee Mi while interviewing him. Refugees are not permitted a whole, integral character by those opposed to their presence in their host countries; they are reduced to fragments, to the worst stereotypes or embodiments of the fears of those who use or believe in such designations.

Replete with graphic descriptions of sexual encounters, “God 99” strips the act of sex itself down to its bare bones — putting it on par with the other bodily functions, which Blasim makes sure to relate in equally crass terms. “I wrote about the forms that pubic hair takes, the types and colours of nipples, smells and facial expressions at the moment of orgasm, licking and sucking, descriptions of the forms and sizes of arseholes, the taste and the mixture of funny and serious things we say while fucking,” Owl narrates. While Owl’s gratuitous objectification — frequent, or even redundant and tedious — may seem like the product of a ponderous male gaze, it is nevertheless consistent with the motif of crude fragmentation. Again, “God 99” reduces body parts to a disembodied state, eschewing any pretense to the sublime. What would constitute shock tactics in most other contexts are, or may be, more forgivable here.

Blasim exposes jarring subject matters — and relates painful realities, or aspects of them — in his book’s fragmented structure, potential for confusion and unapologetic prose. (Jonathan Wright, who also translated “Frankenstein in Baghdad” and Blasim’s other short stories, took on the original Arabic prose in “God 99” as ably as ever.) “They call me a ‘dirty writer’ — they say that I do not respect the language,” Blasim said in an interview for The Guardian. “Nobody can touch classical Arabic because it is a holy language. But nobody uses (that) language on the street. And when I dream it is not in classical Arabic.” And, anyway, the realities of the “God 99” story are no sweet dreams.

“God 99” is a spelunking mission, a descent into the stark ugliness and profanity so far removed from the holy — a not-so-subtle irony considering its title. It is also the written equivalent of a middle finger raised to the censorship of those who claim to act in the name of God and on behalf of moral values, like (but not limited to) ISIS, but whose actions result in more misery and bloodshed because of their chokehold on humanity.

After all, a story cannot kill. Or can it? Those who have read “God 99” will understand the allusion.

Grotesque, “God 99” is a perfect vehicle for the horrors of war and refugee trauma that are impossible to convey through statistics, the consumption of which is often a passive experience that cannot compare to the reality of coming across severed limbs in the streets. “Life is a shock and only delusions help us to accept its cruelty and strangeness,” says one character. Another: “Only myths are good for this world — gory, frightening, violent myths, stories in which reality dies and delirium is born, stories that set the imagination free like an angry and wounded animal.” Yet another: “Whenever we are overwhelmed by the strangeness and cruelty of the violence, imagination has been the spare lung by which we breathe when we are trapped in nightmares.”

Three commentaries provide perspectives on the power of the false to serve as a salve for the burns of reality. But the extent to which reality dies in the presence of an imaginative interpretation of this reality is irrelevant when the very suggestion generated by the myth/the fictive/the absurd is the impossibility of conveying the reality of violence. Trauma challenges language, stretching it to its limits. It is one thing to read of an explosion, another entirely to picture “a child whose arms had been blown off in the explosion, making a sound like wings flapping.”

Is visceral disgust or fear, produced in the reader at such images, even an approximation of the reality of beholding the aftereffects of a detonated car in a crowded market? It might not be, but the images are not so easily forgettable.

The history of war imagery and the public spectacle of violence — its proliferation, its deliberate cover-up, its use in propaganda by the likes of ISIS and even American newspapers in order to sell the war on terror, as David Shields describes in “War Is Beautiful” — has been a feature of Iraq’s collective memory and literary strands since the U.S.-led invasion of 2003. In a 2013 article, Iraqi-born translator Yasmeen Hanoosh, who translated into English Luay Hamza Abbas’ “Closing His Eyes,” explains how Iraqi writers, in the decade since the 2003 invasion, challenged many of the norms that characterized 20th-century Iraqi literature, departing from both national narratives under dictatorship and traditional literary constraints. “The strangeness with which the work of many contemporary Iraqi writers at once rivets and disorients the reader,” she writes, “is perhaps the best metaphor for the incongruity of modern Iraq’s cultural and political history.”

From magical realism to horror and trauma literature that explores the individual and collective psychological effects of war, this inventive fiction has seen an unprecedented expression in Iraqi writers who have sought to sift through and render the violence that has so long been a feature of life in Iraq. A famous example is Ahmed Saadawi, whose “Frankenstein in Baghdad” took home the International Prize for Arabic Fiction. Saadawi’s novel, set in U.S.-occupied Baghdad, tells the story of a man who collects human remains from the sites of explosions, assembling them together to form a corpse in the hopes that the dead individuals that compose it might receive a proper burial. The corpse becomes animated — and it begins to seek vengeance for its many victims of violence, morphing into a monster that quickly spirals out of its creator’s control. In “The Corpse Washer,” Sinan Antoon writes in a similarly innovative vein; with his frequent use of dream sequences, however, Antoon favors an approach that focuses on the psychology of trauma rather than the supernatural. He tells the tragic tale of a “body-washer” — or mghassilchi — forced to abandon his career in art to tend to the bodies and body fragments that rapidly pile up in post-invasion Iraq, itself a corpus dismembered by the sectarian violence that surged in the aftermath of the U.S. incursion and its “Mission Accomplished.”

None of the imagery or spectacle can be divorced from “God 99” or other works by Blasim and Saadawi. From the sanitized, video game-like footage of the 1991 Gulf War and the exclusion of footage considered too graphic to show to the public (in both gulf wars), to the scandals of Abu Ghraib and of the bodies-for-porn NowThatsFuckedUp.com, to the Hollywood-style execution footage of ISIS, the violence carried out against Iraqis and either covered up or captured and disseminated online has constituted a sort of visual assault on the dignity of the dead, with little justice or accountability to show for it.

Blasim’s “God 99” reflects this lack of accountability; his characters suffer a myriad of cruelties — from brutality at the hands of border guards and police to the quotidian explosions — without receiving even a semblance of justice or closure. The lack of resolution in the conclusion of “Frankenstein in Baghdad” is an excellent representation of violence with no end in sight, and, similarly, an open-ended finish to “God 99” draws the reader back cyclically to the beginning of the novel, suggesting the impossibility of closure. Both novels lay bare violence in unflinching detail; nothing is too graphic for their pages, and any reader with a lingering belief in myths — of anything other than the naked vulnerability of the individual — is swiftly disabused of those illusions.

“I really envy you this mixture of reality, whether it’s lurking behind the door or the window or between the walls, and of that black surrealism that is the fruit that hangs high in the tree!” Mardan writes to Owl in one of her emails, adding that she is writing a new story in which “myths from reality are mixed with something else close to that black surrealism of yours.” It is Blasim’s “black surrealism” and powerful experimental lens that allow for an unfettered exploration of topics like war and the refugee experience that have been subject to endless obfuscations, when their reality is rooted in the flesh, bones and blood of their silenced victims.

Of course, realism undeniably has its place, as does most quality fiction in this realm, with its power to respond to the desensitizing effects of conflict reporting by fostering empathy and individualizing otherwise impersonal masses. Even so, stories that defamiliarize the horrors that have been made less horrifying and more familiar through 24-hour news cycles prompt the reader (especially the reader far removed from these horrors) to reconsider their assumptions: Is the impossibly absurd any more so than the commonplace violence to which we are accustomed?

Calling on writers to contribute to his project in his foreword to “Iraq + 100,” Blasim advised them that “writing about the future would give them space to breathe outside the narrow confines of today’s reality.” “God 99” is not set in any specific future. Rather, it is grounded in the real experiences of refugees, offering a similar space to explore beyond the confines of a reality taken for granted. Ultimately, “God 99” shows us something more akin to a nightmare that, while inspired by real events, reflects those events back through a carnival mirror, defamiliarizing them and accentuating their inherent absurdity.