As a popular movement, antinatalism began to reach a wider audience in the mid-2000s, when South African philosopher David Benatar released a manifesto, “Better To Have Never Been: The Harm of Coming Into Existence” (2006). In it, he argues that the presence of pain is bad, while the absence of pleasure is not. Since life is inevitably painful, it’s unethical to beget new ones. As for the unborn, you can’t regret a happy existence they were highly unlikely to have.

Whatever you make of his arguments, birth rates around the rich world have been plummeting for well over 60 years, as demographers are keen to point out. Two-thirds of all countries are now under the replacement rate of 2.1 births per woman. At 0.55, South Korea is projected to lose 30% of its population by 2070. Outside of Africa, the world’s population will soon be shrinking.

Of course, this great demographic shift is more due to social and economic conditions than existential calculations. As Hans Rosling shows in “Factfulness,” women’s empowerment is the best way to reduce burdensome family sizes. Getting girls into school is far more effective than actions like those of Indira Gandhi, the Indian prime minister who oversaw the brutal mass sterilization of over 8 million low-income men in 1976 alone.

Such radical birth control measures were also put in place to solve social concerns, not philosophical ones. In that sense, today’s antinatalist movement is distinctive. But it’s far from new or unique. In the 1930s, Romanian existentialist E.M. Cioran built a career on a similar outlook in “The Trouble with Being Born.” “Better to be an animal than a man, an insect than an animal, a plant than an insect, and so on. Salvation? Whatever diminishes the kingdom of consciousness and compromises its supremacy.”

If biting, his were hardly new insights, even then. In “The Histories,” Herodotus mentions a Thracian tribe that mourns its members’ births and celebrates their deaths: “When a child has been born, the nearest of kin sit round it and make lamentation for all the evils of which he must fulfill the measure, now that he is born; but when a man is dead, they cover him up in the earth with sport and rejoicing, saying from what great evils he has escaped and is now in perfect bliss.”

In one of the most imaginative productions in recent memory, a brilliant new Turkish Netflix show, “A Round of Applause,” tackles these existential themes with dark insight and biting humor. Written and directed by the talented Berkun Oya, who also made “Ethos,” Turkey’s first critical Netflix success, the six-episode miniseries is a scathingly funny take on the human condition, seen from the perspective of one miserable bourgeois family in Istanbul. The questions it poses are enormous: Can we transcend nature and nurture? Do we know what’s best for ourselves? Can we choose to lead meaningful lives? Is life really worth living?

Proving, perhaps, that “each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” “A Round of Applause” follows the trajectory — spoiler alert — from conception to death, of one precocious man, Metin, who is played with equal talent and fervor in various stages of life by Rezdar Tastan, Eyup Mert Ilkis and Cihat Suvarioglu. As we learn in the first episode, somewhat unscientifically, Metin had been a vitamin in an orange before his future mother, Zeynep (Aslihan Gurbuz), a depressed yuppy, ate him. Now arbitrarily transformed into a 9-month-old fetus, we meet him in her womb, umbilical cord in one hand, cigarette in the other.

“I miss the peace I had between those orange membranes,” laments the morose and fully bearded Metin. “Longing for one’s homeland is such an awful thing.” Metin’s mother, though about to burst, has gone to the polls to vote. While his father Mehmet (Fatih Artman), waits in line, she sits on a bench next to another pregnant woman, working-class and very young. Though the two women do not speak to one another, their fetuses conduct one of the great dialogues in recent television history.

Kudret, the working-class fetus, is depicted as a middle-aged man with a thick black mustache who resembles Ibrahim Tatlises, a famous folk singer in Turkey with Kurdish and Arab roots. A leftist romantic, he waxes poetically about the beautiful days that lie in store for each of them. Metin, already a hardened cynic, is dismissive, though he’s glad Kudret “found his thing.” He blames his own despondency on his mother. Her womb, as we can see, is a messy, murky place, cluttered with the detritus of cheerless days. “This woman hasn’t been happy a day in her life! She could meditate all day and it wouldn’t help a thing.”

Over cigarettes, Kudret tells him his own creation story, a tale of bootstrap solidarity born in the rock-hard fibers of a sour green apple. Find your thing before you leave, he urges his cellmate; it doesn’t matter whether it’s politics, agriculture, basketball, law, religion or model planes. “It’s election day upstairs. Maybe that’s not a coincidence. Now’s your chance to make your choice. Find a struggle, fight for it all your life, then kick the bucket and go. Then it’s back to apples and oranges again. One day you might not be able to afford therapy; I don’t want to see you jumping off a bridge in the news. Please don’t cause a traffic jam. People have stuff to do.”

Metin, suffice it to say, becomes a brilliant boy and a highly precocious teenager, deeply unhappy at every stage of life. His father is initially impressed by his brilliance; his mother is forgiving to a fault. The morning after he’s born, for example, his parents wake up to find him missing. They look everywhere, but there’s no sign of him. Back at the hospital, the doctors do a bit of prodding and discover that, overnight, he surreptitiously crawled back into his mother’s womb. The chain-smoking fetus really meant what he said about not being born.

A hilarious discussion about free will, individual agency and collective responsibility ensues. The nurse, for example, suggests that his parents respect his wishes. “It’s a remarkable achievement. This individual made a huge decision of his own free will. Doesn’t this performance deserve a round of applause?” a nod to the show’s title. Blinded by motherly pride, Zeynep is flattered. You’ve got to respect his individual choice, adds the nurse. To act otherwise is against the zeitgeist!

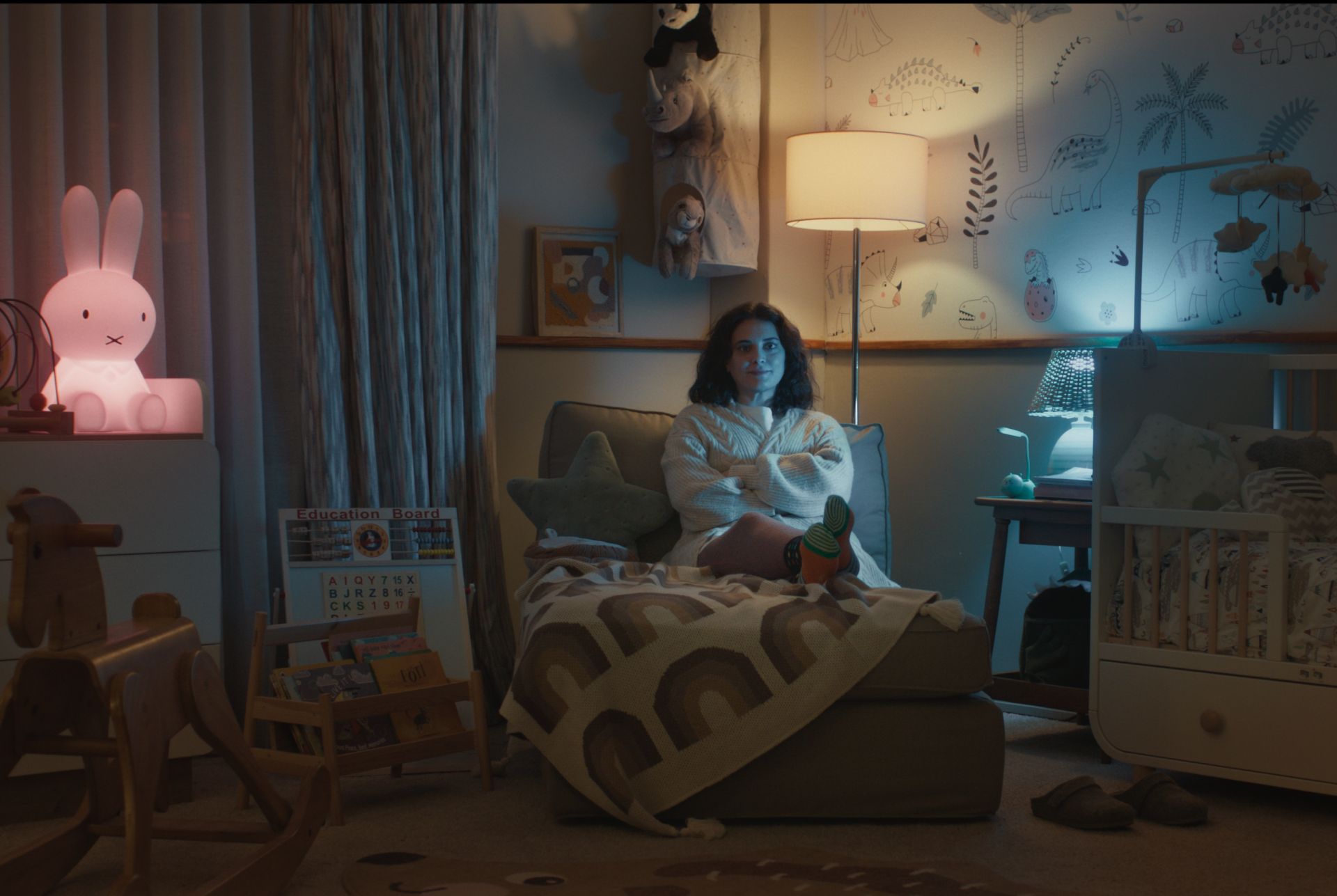

Mehmet and Zeynep, now pushing 40, have never been happy. Many scenes start with the same dismal image: her meditating on the living room floor of their expensive Istanbul flat while he stares dumbly at her from a nearby chair. It sums up everything wrong with upper-middle-class wellness-ness, Oya seems to be saying: a rootless culture of false gestures, faux spirituality and grasping unhappiness. Like many well-heeled directors, the object of Oya’s wrath — and pity — is often his own class. Are they really beyond redemption?

In the hospital waiting room, Zeynep receives a phone call from Mehmet, her husband. Though he’s standing next to her, we hear an alternate version of him on the phone. “Answer it! See what I have to say!” One of the show’s most heart-wrenching scenes ensues. “Look at our baby,” Mehmet coos. “What willpower. What incredible resolution.” Meta-Mehmet, it turns out, is a very different man: confident, direct, honest, supportive and open — even, for the first time, sexy. “If we take him back out, aren’t we disregarding his first deliberate decision as a free individual?”

They go on to have the only honest conversation in their lifelong marriage. Zeynep, for her part, admits that she doesn’t love him. While pretending to meditate, she tells meta-Mehmet, she’s really scrutinizing their relationship. “Do we even have a connection? Are we not just making this baby to not get divorced?” Only meta-Mehmet has the courage to listen and empathize, since the real one lives in a fog of cuckolded conformity. They end the call in sweet, honest, intimate terms: He’s surprised, but relieved to know the truth. In some alternative universe, maybe it really does set you free.

Like all great comedies, “A Round of Applause” leaves no social stone unturned. Not only does contemporary Turkey come in for criticism, with its tortured efforts to straddle the line between tradition and modernity, religion and faithlessness, individualism and collective solidarity, but “Homo disenchanted,” as Max Weber might have called us, must also go to the scaffold. We see it best in the 5-year-old version of Metin, a sensitive, hyperarticulate little fellow who carries the show to new heights in Episode 3.

Dwelling on his first breakup, he sits alone in the stairwell of his parents’ upscale building. His ex, a charismatic, no-nonsense girl, comes to check on him. “I feel this emptiness inside,” he confesses. “Stop running around in circles,” she reprimands him. “We broke up a whole eight hours ago! We need to move on with our lives. The girls outside are having a throwback day: drawing with chalk, jump rope, marbles, hopscotch. Afterwards we’re throwing an ’80s party. Stop depressing us all and come have some fun.” He replies that the past isn’t just a theme party for him. She calls him a killjoy who will wind up alone. “I already am alone!”

“We’re all alone!” cries the witty 5-year-old. “It’s not just you — it’s all of us! We’re just not arrogant like you about it. We all feel the same emptiness inside. But we throw ’80s parties instead of drowning in it.” Rather than heed her advice, Metin sets off on a lonely self-indulgent stroll around solemn parts of wintry Istanbul, a brilliant ode to dozens of depressive Turkish films. In the background blasts Ahmet Ozhan’s 1984 classic, “Huzun,” an untranslatable Turkish word somewhere between sadness, soul-sickness and melancholy. “Huzun,” cries the famous ’80s ballad, “from time to time, comes in giant waves, crashing on the shores of my heart.”

The problem, hints Oya, in the violent struggle between free will and determinism, is that Metin has made up his mind — and the result is the opposite of “amor fati,” whereby the Stoics instruct us to “love our fate.” Metin, for his part, almost seems to enjoy his misery, a kind of masochistic fatalism. Horrifically, through every stage of life, he also remembers the orange. This is the near-religious nature of the show, which suggests, like many of the world’s most prominent faiths, that our real home is not really on this Earth.

Marx famously said, “The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.” Metin might agree. Contrast this with a meme making the rounds that asks readers to consider the near-miraculous ability of their ancestors to survive. Go back 12 generations, it says, and we each have 4,094 ancestors (four grandparents, eight great-grandparents and so on). Think for a moment, it urges us. How many struggles? How many battles? How many difficulties? How much sadness? How much happiness? How many love stories? How much hope for the future did your ancestors have to hold on to for you to exist in this present moment?

In the opening episode, Mehmet has a nightmare. What if their baby turns out like the horrible friends they had over for dinner earlier that evening: selfish, whiny, immature, needy, narcissistic smartphone addicts — fully infantilized adults. “I guess they’re a little spoiled,” says Zeynep, “but isn’t everyone these days?” That’s the point, says Mehmet. This is how people are now. Our child will be more or less the same. Born in this city with no money problems, how could he be any different?

In “The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World,” David Anthony gives a nice rebuttal to Mehmet, Metin and the antinatalists: “When you look in the mirror you see not just your face but a museum. Although your face, in one sense, is your own, it is composed of a collage of features you have inherited from your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and so on. The lips and eyes that either bother or please you are not yours alone but are also features of your ancestors, long dead perhaps as individuals but still very much alive as fragments in you.

“Even complex qualities such as your sense of balance, musical abilities, shyness in crowds, or susceptibility to sickness have been lived before. We carry the past around with us all the time, and not just in our bodies. It lives also in our customs, including the way we speak. The past is a set of invisible lenses we wear constantly, and through these we perceive the world and the world perceives us. We stand always on the shoulders of our ancestors, whether or not we look down to acknowledge them.”

When it comes to the rest, Kudret-the-fetus might say, take courage and choose.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.