The antique Soviet Tu-134 touched down at Salekhard airport in a slicing crosswind, bunny-hopped twice, then juddered to a halt in front of the terminal with a macho squeeze of brakes. Outside the airport taxi drivers waited in their vehicles, waiting in a head-lit swirl of exhaust to close in on the single emerging foreign passenger. From the usual post-Soviet police lineup of grinning crooks, I chose the only one who hadn’t bothered to get out of his car. He was a mash-faced octogenarian with a bulbous alcoholic’s nose who introduced himself as “Ivanych” — short for Alexander Ivanovich. The sky was deep black and sprinkled with stars of extraordinary brightness. It was 4 p.m.

Flying across the Russian Arctic at night, in winter, I experienced an eerie sense of having flown off the edge of the world. As the plane lurched northward, the spots of light that marked towns and roads dwindled to black. North of the 65th parallel nothing was visible but a dreamscape of snowbound, moonlit forest stretching unbroken not just to the horizon but beyond, apparently forever.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn named the network of prison camps that stretched across the Soviet Union the Gulag Archipelago. But in truth, all of Russia is like an archipelago, a string of isolated islands of warmth and light strung out in a hostile sea of emptiness. I wanted to know what traces of the once-vast empire of the Gulag had survived. Salekhard, the western railhead of one of Joseph Stalin’s most maniacal and deadly slave-labor projects, seemed as good a place as any to begin my search.

On the way into town, Ivanych and I passed an impressive steam locomotive mounted on a concrete plinth by the roadside, its front emblazoned with Soviet heraldry.

“Monument to Project 501,” grunted Ivanych as he swung his beat-up Toyota into a right-hand turn. “You know. The Railway of Death they called it.”

In 1947, Soviet state planners decided that the key to opening up the riches of the Arctic was to build a railway linking the great Siberian rivers Ob and Yenisei. Salekhard, near where Ob flows into the White Sea, was to be the starting point. The terminus was to be in Igarka, 800 miles to the northeast, on the Yenisei. Between them lay a landscape of taiga — boreal coniferous forest — and tundra, a wasteland of scrubby bushes that grow in areas where not enough daylight reaches round the curvature of the earth to sustain trees. The railway was to be built on the underlying permafrost — a layer of earth that remains frozen even in midsummer and begins between 3 and 16 feet below the topsoil. Somewhere between 80,000 and 120,000 Gulag inmates, mostly political prisoners, were loaded first onto riverboats and later trains and detailed to build Project 501. They constructed their own prison camps as they went. At least 20,000 never returned.

“Anything left of the railway?” I asked. “Can we go see it tomorrow?”

Ivanych grunted dismissively.

“Anything left? Nothing’s left. Taiga swallowed it. ’S what the taiga does. Swallows everything,” Ivanych replied.

Beyond a ring of crumbling Soviet apartment blocks, central Salekhard was newly built and brightly lit. The city is rich now thanks to a natural resource never imagined by Stalin’s planners — natural gas. The Yamal Peninsula produces enough gas to fill half the European Union’s demand and is connected to Germany through the recently constructed Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines that run along the bottom of the Baltic Sea. Every gas hub in northern Europe has a pipe that leads directly to the Russian Arctic wilderness.

We passed a funfair on which hardy Russian kids rode in frigid, 1.5-degree Fahrenheit temperatures, a central square decorated with illuminated ice sculptures, and a new suspension bridge with a circular restaurant perched at the apex of the central pylon. The Yuribey hotel, haunt of apparatchiks and visiting oil men, was a monument to the budget Dubai-style favored by Russia’s provincial oil towns. The atrium had the obligatory glass elevators and lots of gold-colored trimming. The anxious young receptionist spoke careful, hard-won English. She directed me to the poshest local restaurant, a log-built fantasia frequented by Salekhard’s bourgeoisie which was festooned, hunting lodge-style, with wolf and bear skins.

The following day, Ivanych was due to pick me up at dawn – 11:13 a.m. It was October and only a few weeks later dawn would cease altogether for a month as Salekhard entered the season of round-the-clock polar night. In the pre-dawn dark, I walked to the regional museum and saw ivory artifacts of the ancient Nenets people. I admired reconstructed wigwams and preserved beaded shirts of the Khanty natives (remarkably similar to those of Native Americans). There was a perfectly preserved baby woolly mammoth discovered in the permafrost and an extensive collection of stuffed local wildlife. But only a single, narrow display case contained any evidence of the seismic human tragedy that had put Salekhard on the map — Project 501. A couple of rusty manacles, a hand-painted railway sign faded by the weather, a collection of railway spikes and the iron peephole of a prison door were all that the museum’s curators thought worth exhibiting. A small caption stated that “the tracks were put down ruthlessly, at the edge of the earth, between 1947 and 1953, at the cost of great human sacrifice.”

“Why so little on the Railway of Death?” I asked a museum attendant. She shot me a hostile look. “A zachem o grustnom?” she said — a phrase whose laconic force is almost untranslatable but literally means, “why talk about sad things in the past?” Sometimes Russians’ irony is buried so deep that it’s almost indistinguishable from indifference. With this lady, a formidable middle-aged woman with the figure of a Soviet refrigerator and a hard-set mouth, I could not tell which.

Ivanych and I rolled east along the modern road that shadows the old rail track. In fact, Ivanych was wrong. The taiga had not quite swallowed all traces of Project 501. The raised rail bed, made of gravel and sand shipped down the Ob and painstakingly unloaded by hand by thousands of prisoners, is still clearly visible. So are the timber sleepers and a few rails — those that weren’t stolen in the early 1990s by scrap metal merchants.

Project 501 — and its sister project, 503, which worked westward from Igarka — were abandoned soon after Stalin’s death in 1953. Moscow planners admitted what should have been obvious from the beginning: that there were no resources in Salekhard, and none in Igarka, but timber. The whole project had been a colossal waste of time, resources and life. Over 600 miles of line had been built by the time it was scrapped. Frost heaves — the swelling of the permafrost after the summer thaw — quickly made the line unusable. Hundreds of timber bridges, built (according to Ivanych) by an imprisoned czarist engineer, lasted into the ’70s, when local hunters were still riding sections of the line in homemade rail cars powered by motorcycle engines. To put a stop to the joyriding, authorities torched the remaining bridges and in 1976 cut the final section of telephone line that was the last working remnant of the railway.

About an hour out of Salekhard, past road signs warning drivers of crossing reindeer herds, we came across a settlement of Nenets wigwams. Not tourist wigwams. Real-life, native winter dwellings made of sticks — the only concession to modernity being that they were made of heavy canvas rather than reindeer skin, with iron stovepipes stuck through. By the wigwams, a collection of sleds designed to be hauled by snowmobiles stood under canvas coverings. There was no sign of the inhabitants or their reindeer herds. They’d gone north to forage for frozen grass under the snow, Ivanych reckoned.

I decided to try to follow the railway for a while. Crossing a snowfield crusted with ice took half an hour. The crust gave way every three or four steps, plunging my leg knee-deep into powder. Up on the embankment the going was easier, though the old rail bed was thick with shrubbery. Every few hundred yards was a stream, which would have necessitated a bridge built of timber painstakingly hauled hundreds of miles from the south where normal-sized forests grow. A snowfield dotted with a few timbers poking out from the drifts could have been the remains of one of the camps that were located every 5 or so miles along the railway. By the time I staggered back to Ivanych’s car as dusk was gathering, I was half-frozen and exhausted. The idea of spending months and years in this lethal wind, working every day in the biting cold, “would not fit within the bounds of consciousness,” as Boris Pasternak wrote in the early 1930s. “There was such inhuman, unimaginable misery, such a terrible disaster, that it began to seem almost abstract.”

People cannot live here, I thought. This land is trying to kill you, every second. This place wants you dead.

Ivanych, like almost every older person in Russia’s Arctic cities, was from somewhere else. He was born in Lugansk, now in eastern Ukraine, in 1939. His earliest memory was of hiding from the Germans in a feed box in his family barn, and of it being opened by a young Wehrmacht soldier who gave him and his brother some dry bread. After three and a half years of military service in the navy, he was offered a job as a truck driver in Salekhard. The money was good, so he came. In summer he drove timber trucks from neighboring settlements down to the Ob. Every winter Ivanych’s job was to build an ice road from Salekhard to Nadym through 370 miles of taiga by felling trees and bulldozing snow over them to create a temporary highway. In his youth, most of Ivanych’s co-workers and neighbors were former Gulag prisoners and guards who had chosen to stay even after their release (or sacking) after Stalin’s death. Why hadn’t they gone home, I asked? “Kto ikh zhdal-to?” replied Ivanych, in another phrase whose emotional freight is almost untranslatable. “Who did they have waiting at home for them?”

Ivanych had had a wife, a son and a granddaughter, all of whom had predeceased him — his son through drink, his granddaughter from a drug overdose. He now lived alone in one of the few wooden barrack houses in town that had survived from the 1940s. “Built with conscience,” he said — meaning, built to last — by German prisoners of war. Did he ever think of leaving Salekhard? “What, you think this place is so bad?” he growled, almost belligerently. “What’s wrong with it? You don’t like it?” I liked it.

We stopped for coffee at the city’s sole, almost hipster-ish, coffee bar — a small booth by an open-air market where traders sold frozen meat and fish piled high on their stalls. No need for refrigerators as the temperature dropped toward zero degrees Fahrenheit.

The next morning we headed for Labytnangi, the local railhead and the only section of the Railway of Death still operational. We had one obstacle to cross, the Ob River, nearly 2 miles wide and frozen over since September. During the days of Project 501, they used to lay railway tracks across the ice. In the 1960s, Ivanych would drive tractors across the Ob every autumn to test the ice, walking behind the machine and using ropes to control the steering and accelerator in case it fell through.

Today there’s still no road from Salekhard to the rest of Russia and no bridge across the Ob. In summer the two sides of the river are connected by a ferry, in winter months by an ice road that’s still laid down annually by bulldozing a bed of packed snow surfaced with gravel across the river’s surface. But when we arrived, the Ob had not yet frozen solid enough for the ice road to be finished. Therefore all the city’s produce and passengers had to be ferried across either by a pair of small, Soviet-built, 20-seater hovercrafts or by freelance snowmobile drivers who take their chances to haul sleds containing half a ton of groceries and food across the new-formed ice.

A group of sled men, swaddled in heavily padded winter overalls, stood in a circle by their vehicles discussing the latest news. One of their colleagues — apparently some inexperienced young idiot from Labytnangi — had fallen through the ice during a run the previous day. Amazingly, lifeguards on the shore had managed to follow the guy’s drowning body drifting downstream by watching through the semi-transparent ice, drilled a hole where they estimated he would soon appear and hauled him out. Alive.

Evidently, this was not an unusual occurrence. The guys were more concerned about how the unfortunate driver would be able to compensate the snowmobile’s owner for the loss of his vehicle. They offered to take me across for $7 — the going rate for a half-ton load.

I said I’d prefer the hovercraft.

Great machine. Built in 1989, the roaring monster traveled at a steady 75 mph, zipping with ease over both ice and a still-unfrozen section of black, open water. After we had crossed, I ducked into the cockpit (bizarrely enough, it had the same dashboard and steering wheel as a standard Soviet Gazelle light truck), and the driver offered to sell the machine to me for $150,000. That’s actually a good price for a small Soviet passenger hovercraft — I checked — even though the gas mileage sucks, just over 2 miles per gallon of fuel.

Said, a craggy 60-year-old Muslim from Dagestan in the North Caucasus, was the only taxi driver on the Labytnangi side. He drove me around what little there was to see of his adopted hometown — railway sidings, rows of sagging wooden barracks, peasant huts and a handful of 1950s five-story apartment buildings constructed to entice free workers to live in the North after the Gulag was disbanded. Like Ivanych, Said had come to the Arctic in Soviet times for the bonus wages paid to people willing to work in tough conditions.

“Some neighbors said it was good up here,” he said. “So I came.” He had spent most of his working life as a miner in the deep coal shafts of nearby Inta. When he was 29, he had been trapped underground with 17 other men for three days after a collapse. They had survived by taking turns to breathe from their compressed air bottles. After they’d been dug out by rescuers, the survivors were sent to a Black Sea sanatorium for a month’s holiday. Then they went right back down the mine again. How did that feel? “Normal’no. A chto?” Said replied with a shrug. “Fine. So what?” He drove me to a plot that he and a few fellow local Muslims had bought to build themselves a small mosque. “Wherever you are, you can make it like home,” he said.

The train to Vorkuta was so long you could barely see one end from the other. It consisted of open (empty) coal wagons and gray-painted goods cars. There were only three passenger carriages. There was no first class car on this train – the best carriage was “kupe,” or second class, with four-berth sleeping compartments. “Platskart” was third class with open six-berth compartments. The last — “sidyashyy” — had basic bench seats. The platforms were pungent with the smoke from the coal stoves that are still used to heat every long-distance Russian Railways carriage. My compartment was clean and supremely cozy, the bedding folded in starched triangles. The conductress brought me tea drawn from the coal-fired boiler in a glass with a metal holder. I was one of only two passengers in the carriage.

The thousands of prisoners transported on this railway in the 1940s were less lucky. They were packed in cattle cars, often cooped up for weeks. The guards would refer to them as “white coal” and offload corpses at every stop. The first thing a prisoner would have seen on their arrival at Vorkuta was a sign that said: “Work in the USSR Is a Matter of Honor and Glory.” Another declared: “With an Iron Fist, We Will Lead Humanity to Happiness.” A taste for sadistic irony was just one of the many traits that Nazi Germany and Stalin’s USSR shared.

In all, some 18 million people passed through the Gulag system from 1929 until Stalin’s death in 1953, according to the Soviet state’s own records. Of those, contemporary scholars estimate that some 6 million died either in prison or shortly after their release. Like Hitler’s concentration camps, Stalin’s Gulag housed both political prisoners and common criminals as well as people condemned for living in politically unreliable nations such as Poland, Chechnya and Ukraine or who were members of the wrong class, whether wealthy peasants or prerevolutionary aristocrats. In the closing days of World War II, the Gulag population was swelled by German war criminals and ordinary German prisoners of war, as well as hundreds of thousands of Soviet soldiers who had chosen surrender over death and were therefore presumed to be collaborators with the enemy.

The prison camps that dotted the Soviet Union were called “colonies” for good reason. Though some gulags were located in the middle of large cities — many housing imprisoned engineers and scientists who worked in prison laboratories — most penal settlements were tiny islands of precarious life in a hostile, unexplored territory.

Few colonies were more remote or hostile than Vorkuta. In the late 1920s, Soviet geologists identified vast coal deposits in the frozen taiga where the Pechora River flowed into the Arctic Sea. The region was some 1,200 miles north of Moscow and 100 miles above the Arctic Circle. Soviet secret police lost no time in arresting a leading Russian geologist, Nikolai Tikhonovich, and setting him to work organizing an expedition to sink the first mine in the area. In the early summer of 1931, a team of 23 men set off northward from Ukhta by boat. Prisoner-geologists led the way, ordinary prisoners manned the oars, and a small secret police contingent was in command. Paddling and marching through the swarms of insects that inhabit the tundra in summer months, the party built a makeshift camp.

“The heart compressed at the sight of the wild, empty landscape,” recalled one of the prisoner-specialists, a geographer named Kulevsky quoted in Anne Applebaum’s Pulitzer-winning study “Gulag: A History.” “The absurdly large, black, solitary watchtower, the two poor huts, the taiga and the mud.” The beleaguered group somehow survived their first winter, when temperatures often fell to 40 degrees below zero and the sun sank below the horizon for the monthlong polar night. In the spring of 1932, they sank the first mine at Vorkuta using only picks and shovels and wooden carts.

Stalin’s purges — the mass arrests of suspect Communist Party members and politically unreliable wealthy peasants — began in 1934 and provided the slave labor needed to turn this desolate site into a major industrial center. By 1938, the new settlement contained 15,000 prisoners and had produced 188,206 tons of coal. Vorkuta had become the headquarters of Vorkutlag, a sprawling archipelago of 132 separate labor camps that covered over 35,000 square miles — an area larger than Ireland. By 1946, Vorkutlag and its neighbor Rechlag housed 62,700 inmates and was known as one of the largest and toughest camps in the entire Gulag system. Overall, nearly 2 million prisoners passed through Vorkuta’s camps beginning in the early 1930s for three decades — an estimated 200,000 of whom perished from disease, overwork and malnourishment in the Arctic conditions.

The Salekhard-Vorkuta train took over 9 hours to cover the 370-mile distance, the locomotive rolling slowly over the rickety, prisoner-built track. The train toiled for two hours up a long gradient through thick pine forests, crossing steel girder bridges that had replaced the old timber ones. At the top of the rise a spectacular spur of mountains appeared in the moonlight, bright white and craggy. This was the northernmost end of the Urals — technically, the border between Asia and Europe. I dismounted to smoke during a long stop at a single-platform station. The settlement contained no more than a dozen houses, all log cabins sunk deep in snow and absolute, stark winter silence. The place was both beautiful and terrifying in its utter loneliness.

The train turned north at Yeletsky, and beyond its double-glazed windows the taiga forest began to thin out and the pines to shrink in size. Then, abruptly, the trees ended in a sudden line, replaced by a vast and empty snowfield. The moon began to set. Half an hour south of Vorkuta, my mobile phone found a feeble signal and downloaded a single message. It was from the airline I had booked for the return journey to Moscow. “Your flight has been delayed,” it said. “New departure date: March 3.” A 17-week delay.

Vorkuta city appeared in a haze of yellow streetlights — high-rise 60s and 70s concrete outskirts first, then grander Stalin-era buildings as we drew toward the center. The station was a long, low, neoclassical barn surrounded by once-grand, three-story brick apartment houses that had long ago been abandoned. A handsome boulevard that connected the station to the main square was similarly lined with empty buildings. A colonnaded theater nearly as grand as the Bolshoi in Moscow dominated one side of a municipal square. (Its first director would have been at home; he had been the boss of the actual Bolshoi before his arrest.) A more sinister Brezhnev-era monstrosity that bore the blue logo “Severstal” took up another. A few pedestrians hurried down wide, clean-swept boulevards. There were few cars.

Between the two sliding doors of a small shopping center, a group of deathly pale teenagers loitered, prevented from entering by a tired old security guard in a baggy uniform. This was the entrance to the Hotel Vorkuta. The kids stopped chatting and stared as I passed inside, ruining their hangout with a blast of cold street air. I ruined it again on the way out to the neighboring sushi parlor, the only place open, part of a grim food court also full of teenagers who took turns sipping a single soda. All the sushi on the menu contained Philadelphia cheese.

In the pitch-dark early morning Fyodor Nikolayevich, a local historian and retired strategic missile forces officer, waited for me by his Lada. He was a spry 46-year-old with the same unhealthy pallor of the previous night’s teens but offset by a cheerful smile. He was determined to show me the bright side of the city he’d moved to as a young soldier and never left.

We began in the oldest part of town, or rather, in its ruins. The first generation of mining engineers and geologists had lived in earth dugouts. When timber arrived from the south, carried by barge in summer to the closest river port, then hauled overland by hand on sleds the following winter, they built flimsy shacks. As soon as the railway arrived in the mid-1930s, proper building materials could be brought up. The settlement of Rudnik (Russian for “ore deposit”) was born. Because the ground was — and still is — frozen solid year-round, the foundations had to be built on piles hammered into the icy earth. But over time, buildings have a natural tendency to thaw the permafrost underneath them, so Vorkuta’s first geological institute, school and apartment buildings all soon cracked and toppled. Even the suspension bridge to Rudnik has crumbled away, leaving a video game-like wasteland of derelict buildings occasionally frequented by young couples and the odd urban-ruin adventurer during Vorkuta’s brief summer. In winter the abandoned streets and derelict bridge are too slippery and treacherous even for them.

It was the same story around Lenin Square. A large cultural center, a Lenin statue, and streets and streets of neoclassical houses all stood gutted and empty. A long-abandoned swimming pool and sports center were around the corner, flanked by a row of empty shops and yet more, slightly more modern concrete apartment buildings. Small, scrub-like trees grew through cracks in the pavements and out of the cornices of the buildings. The entire center of 1940s and ’50s Vorkuta had been left to disintegrate, a monument to the USSR’s colossal profligacy with everything from bustling materials to human lives. “Cheaper to build in another place than repair the old buildings,” explained Fyodor.

This well-planned center was where the administrators of the Vorkutlag empire lived with their families — the Gulag officers, the engineers, architects and specialists who volunteered to work here. The masters of this prison empire lived lives of comparative luxury. “Life was better than anywhere else in the Soviet Union,” remembered Andrei Cheburkin, a foreman in the Arctic nickel-mining Gulag of Norilsk, quoted by Applebaum. “All the bosses had maids, prisoner maids. Then the food was amazing. There were all sorts of fish. You could go and catch it in the lakes. And if in the rest of the Union there were ration cards, here we lived virtually without cards. Meat. Butter. If you wanted champagne you had to take a crab as well, there were so many. Caviar … barrels of the stuff lay around.”

For the prisoners, however, the living conditions were shockingly different. Most lived in flimsy wooden barracks with unplastered walls, the cracks stopped up with mud. The inside space was filled with rows of knocked-together bunk beds, a few crude tables and benches, heated by a single, sheet metal, coal stove. In photographs of Vorkuta taken in the winter of 1945, the barracks are almost invisible — their steeply sloping roofs come almost to the ground so that the snow accumulating around them would insulate them from the bitter Arctic cold.

Vorkutlag held every kind of prisoner, from the commander of Germany’s Sachsenhausen concentration camp, Anton Kaindl, to famous Yiddish, French and Estonian writers. Russian art scholars and painters; Latvian and Polish Catholic priests; East German Liberal Democrats and even a British soldier who had fought with the Waffen-SS British Free Corps were on the prisoner rolls at the end of World War II. Alongside the intellectuals and war criminals were a large population of murderers and rapists and even several convicted cannibals.

For 10 months a year, the intense cold was a constant, lethal companion of Vorkuta life. “Touching a metal tool with a bare hand could tear off the skin,” recalled one prisoner quoted in ‘Vorkuta: City of the Strong,’ a 2018 collection of memoirs. “Going to the bathroom was extremely dangerous. A bout of diarrhea could land you in the snow forever.” And prisoners were woefully, badly equipped to deal with the brutal climate. In Vorkuta, according to camp records, only 25% to 30% of prisoners had underclothes, while only 48% had warm boots. The rest had to make do with makeshift footwear made from rubber tires and rags.

The Arctic summer of Vorkuta, when the scrubland bloomed with scarlet fireweed and the low-lying landscape turned into a vast bog, was scarcely more bearable. Mosquitoes and gnats appeared in huge gray clouds, making so much noise it is impossible to hear anything else. “The mosquitoes crawled up our sleeves, under our trousers. One’s face would blow up from the bites,” recalled a Vorkuta inmate quoted by Applebaum. “At the work site, we were brought lunch, and it happened that as you were eating your soup, the mosquitoes would fill up the bowl like buckwheat porridge. They filled up your eyes, your nose and throat, and the taste of them was sweet, like blood.”

Escape was unthinkable. Some of the more remote camps had no barbed wire, so remote was the possibility of prisoners ever making it across hundreds of miles of wilderness to freedom. Those who did attempt escape did so in threes — the third prisoner coming along as a “cow,” the food for the other two in case they didn’t find any other nourishment.

Prisoners were expected to work 10-hour days — reduced in March 1944 from 12 hours after too many work accidents began to impair productivity — down jerry-built and desperately unsafe coal mines. Records for the year 1945 list 7,124 serious accidents in the Vorkuta coal mines alone. Inspectors laid the blame on the shortage of miners’ lamps, electrical failures and the inexperience of workers.

Coal mining in the Pechora Basin had its heyday after 1942, when the Germans occupied the coal-rich Donbass in Soviet Ukraine and Vorkuta and Inta were the sole providers of energy to a coal-starved, wartime USSR. Yet even after the Soviet victory and Stalin’s death, the mines of Vorkuta remained open — and four are still in production. Today Vorkuta boasts — if that’s the word — Europe’s deepest working coal shaft, a staggering 3,600 feet deep.

The reason is anthracite, an exceptionally pure, deep-mined coal well suited to steel production. Every ton of coal exported from Vorkuta today is taken by rail to the huge Cherepovets steel mill in Vologda province, whose Bessemer converters — steel smelters — are designed to run exclusively on the exact grade of coal produced by Vorkuta. So today both Cherepovets and Vorkuta are company towns run by a single private employer — the Severstal steel company, owned by 56-year-old billionaire oligarch Alexei Mordashov. Severstal owns the local airline, the bus fleet, the newspaper, the hotel, the cinemas, the bakeries and the supermarkets. It has its own railway rolling stock and helicopter fleet and brings Russian pop stars to entertain its workers at Vorkuta’s Bolshoi-style theater, the Miners’ House of Culture.

“Vorkuta used to be run by one corporation — Vorkutlag — now it’s run by another, Severstal,” muses a prominent local journalist who, since she is employed by Severstal, unsurprisingly asked for anonymity. “It’s what people are used to. The government pays half the people who live here — the teachers, nurses, doctors, police, administrators. Severstal pays the rest. It’s a historically comfortable state of being for all of us.”

The four working mines surround the city, joined by a ring road that marks the outer limits of Vorkuta. There is no road out. Like Salekhard, Vorkuta is an island connected to the rest of Russia only by a single train line. Each mine belches both a dust plume of debris blown from the underground shafts and another plume of dark gray coal smoke from its in-house electrical plant. Another coal-fired power station that serves the city and keeps the population from freezing spews even more from four massive chimneys that dominate the skyline. The snow all around Vorkuta is a uniform gray-black from the pollution. Push your boot into it and it looks like a layer cake — snow, coal dust, snow. A recent study by local ecologists of open-source government records found that Vorkuta’s mines and power stations emitted one ton of particulates per person annually into the atmosphere (that is not a typo: one ton, per person, per year). And at their height, Vorkuta’s mines produced 22 million tons of anthracite annually — incidentally, releasing some 57 cubic meters of methane for every ton mined. When burned, the coal from this single city produced 53 million tons of carbon dioxide.

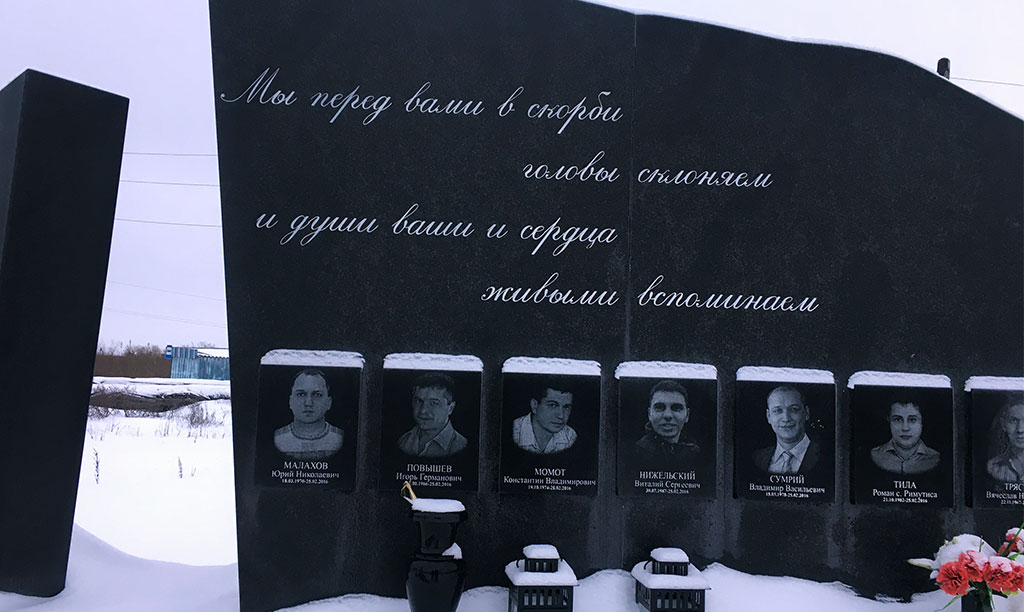

Life above ground in Vorkuta is dangerous and unhealthy. Underground, much more so. The Ring Road is dotted with monuments to miners killed in underground methane explosions, a particular danger of deep anthracite mines. The most recent disaster, in 2016, killed 31 miners and five rescue workers. Their rugged young faces — some taken from family snaps, most from official ID photographs — are etched on black granite plinths around a semicircular patch of cracked stone.

Most of the hundreds of thousands of prisoners who died here of overwork and malnutrition have no such monument. Only a handful were ever buried with something like honor — and those were the foreign prisoners who died in the most heroic, and the most tragic, episode of Vorkutlag’s history.

Stalin died in March 1953. His chief police officer, Lavrentiy Beria, was arrested shortly afterward, following a Politburo power struggle. On a warm July day of that year the prisoners of one Vorkuta camp put down their tools, demanding that inmates have access to a state attorney and due justice. Convicts in neighboring camps, seeing that the mine-head wheels in the rebel camps had stopped spinning, joined the strike. Commanders and guards were expelled, and for a few weeks the prisoners ran their own camps. Top brass from Moscow was sent in. The state attorney of the USSR as well as the commander of the Interior Ministry Troops tried to reason with the strikers. On July 26, prisoners stormed the maximum-security punitive compound, releasing 77 inmates who had been kept in solitary cells, which could spell death in wintertime. Days later, the authorities finally acted, massing armed troops to open fire on the rebels, killing 66 and wounding 135. Many of the survivors were sentenced to further time in jail and missed the general amnesty that followed soon after. In the early 1990s the Hungarian and Lithuanian governments raised handsome memorials over the graveyards of their nationals killed in the uprising. These, and a small, neglected plaque in the center of town, are the only memorials in Vorkuta to Stalinism’s victims.

Seven satellite towns dot the ring road, all with classically downbeat Soviet names: “Northern,” “Arctic,” “Industrial” and (my personal favorite) “Cement.” Fyodor drove me through one, then another. Every one of these towns used to house some 20,000 people. Now, fewer than a thousand remain in each. Some inhabitants live alone in otherwise abandoned apartment blocks. Some staircases are entirely empty, their windows smashed. Many of the apartments, Chernobyl-style, still contain furniture, curtains and pictures. In some buildings the central heating pipes have burst before anyone could turn them off, producing stalactite-like cascades of ice down the stairwells. The schools and shops are a wilderness of broken glass and smashed tiles — all presided over by cheerful Soviet mosaics of smiling children and leaping athletes. Communist Party slogans in patchy scarlet tiling soar up the side of buildings. And yet among all this desolation a handful of windows are still illuminated, small grocery shops are still open and couples are still huddling by bus stops. In one shop in Severny the owner — a Georgian from Batumi — offered to sell me his brother’s three-room apartment for $400. Why did he stay here? “I’m used to it,” he said. “And I’m waiting for the authorities to give me a better place to live. We all are.”

If anywhere is the end of the earth, it’s here — in every sense. Vorkuta is obscene. Obscene in its rape of the earth, its wanton waste of resources, its reckless poisoning of its own inhabitants and the planet. The very ground is doubly poisoned, both physically and karmically. It’s a historical crime scene and an ongoing ecological disaster zone. Tragedy is Vorkuta’s gravity. And it pulls you down, powerfully.

The place is against nature — again, in every sense. Back in June, Fyodor’s wife bought a potted mint plant that she wanted to grow on her windowsill. It died for lack of light. Even during the summertime polar day — when the sun never sets — the angle of the sun is so low that the earth’s atmosphere filters out nearly all the ultraviolet light. Almost no living thing can survive here — least of all human beings.

And yet they do.

Wonderful, clever, warm people like Fyodor and my anonymous journalist colleague live here, voluntarily, still inhabiting an experiment conceived by one of the bloodiest dictators from the last century. Is that a tribute to human spirit and optimism? Or to foolishness and fear and lack of imagination? In 1989, the population of Vorkuta was 200,000. Today, it’s 55,000 and falling. According to the local journalist, Mordashov longs to sell off Cherepovets Steel — or at least to get new smelters that will allow the company to dump its cripplingly expensive Arctic coal supplier. If and when that happens, this city will switch off like a light. In months, it will resemble its abandoned center and outskirts: a terrible monument to human cruelty and folly.

One thing remained — to head into the taiga in search of some remains of the ordinary prisoners who lived and died in the camps around the city. Fyodor drove me past a reindeer farm — we bought venison biltong — and out past the ring road into the open snowfields beyond. I left Fyodor in the car and began to walk cross country toward the setting sun. The ground undulated like waves from the underground roiling of the permafrost. The tiny 2-foot-high trees here grow so slowly that many are over a century old. Even here, miles out of town, industrial trash was everywhere, scattered like the shed skin-flakes of a dirty Soviet behemoth. A rusting boiler, a tractor engine block, a half-ruined blockhouse, rows of telegraph poles leading to now-vanished prison camps. There were no birds or wildlife.

The sun dipped between the clouds and the horizon, briefly illuminating the desolate snowscape in a brilliant golden glow of extraordinary beauty. In the distance, far to the south, the outlines of the Urals stood out pink and white against the darkening eastern sky. A keening wind, blowing down from the White Sea, cut through my thick Soviet military coat, reaching through like a thin probing hand, intimate and dangerous. The world seemed to have stopped, frozen in its tracks, and the air was so cold it burned my lungs. The cloudy sky was like a cold pearl, bleached of color. Under my feet the snow creaked like floorboards.

It seemed amazing to me that millions of the people imprisoned here found the strength to not simply give up. Varlaam Shalamov, a writer who survived 17 years in Kolyma in the Soviet Far East, defined what it means to feel fully human in the Gulag. “I believed a person could consider himself a human being as long as he felt totally prepared to kill himself,” says a character in one of Shalamov’s ‘Kolyma Tales,’ based on the author’s own Gulag experiences. “It was this awareness that provided the will to live. I checked myself — frequently — and felt I had the strength to die, and thus remained alive.”

Yet it is so easy to die here. All it takes is simply to do nothing. To falter in your battle for life for just a few minutes. Kneel down, bathed in this beautiful deadly whiteness. Breathe in the winter and drown slowly in its anesthetic embrace. How strange it would be to go into the darkness amid all this blinding winter light, I thought, under this silken sky as big as the world.

And then the sun set.