In February 2023, New Zealand authorities discovered a strange pink-and-black pontoon bobbing back and forth in international waters near the Cook Islands. On closer inspection, they saw that the jetsam was 81 bales of cocaine, held together with fishing nets and floating on a bed of yellow buoys.

Andrew Coster, New Zealand’s police commissioner at the time, said that the 3.5-ton cache, worth $290 million, was his force’s largest illicit drug seizure “by quite some margin.” It had been flung overboard by a fishing boat, officials familiar with the bust told New Lines.

Had the haul remained undiscovered, they added, it would have been picked up by a second vessel to be smuggled onward — but not to New Zealand, according to Greg Williams, director of the National Organised Crime Group. Williams was adamant that his nation “is not a cocaine market.”

Williams believed the bales were destined instead for New Zealand’s far larger neighbor. Australians pay some of the highest prices on earth for the drug, and their largest city, Sydney, is one of the planet’s most lucrative cocaine markets.

“I always describe New Zealand as Europa to Australia’s Jupiter,” Williams added. But that is changing. For decades, New Zealand’s drug of choice has been methamphetamine, known locally as “P” for “pure.” Traditionally, it came from labs in the jungles of Southeast Asia’s Golden Triangle region, where Myanmar, Thailand and Laos meet. Chinese Triad gangs imported P and distributed it with local biker crews like the Black Power or Mongrel Mob, two fiercely rival gangs whose numbers have traditionally been drawn from Māori youth.

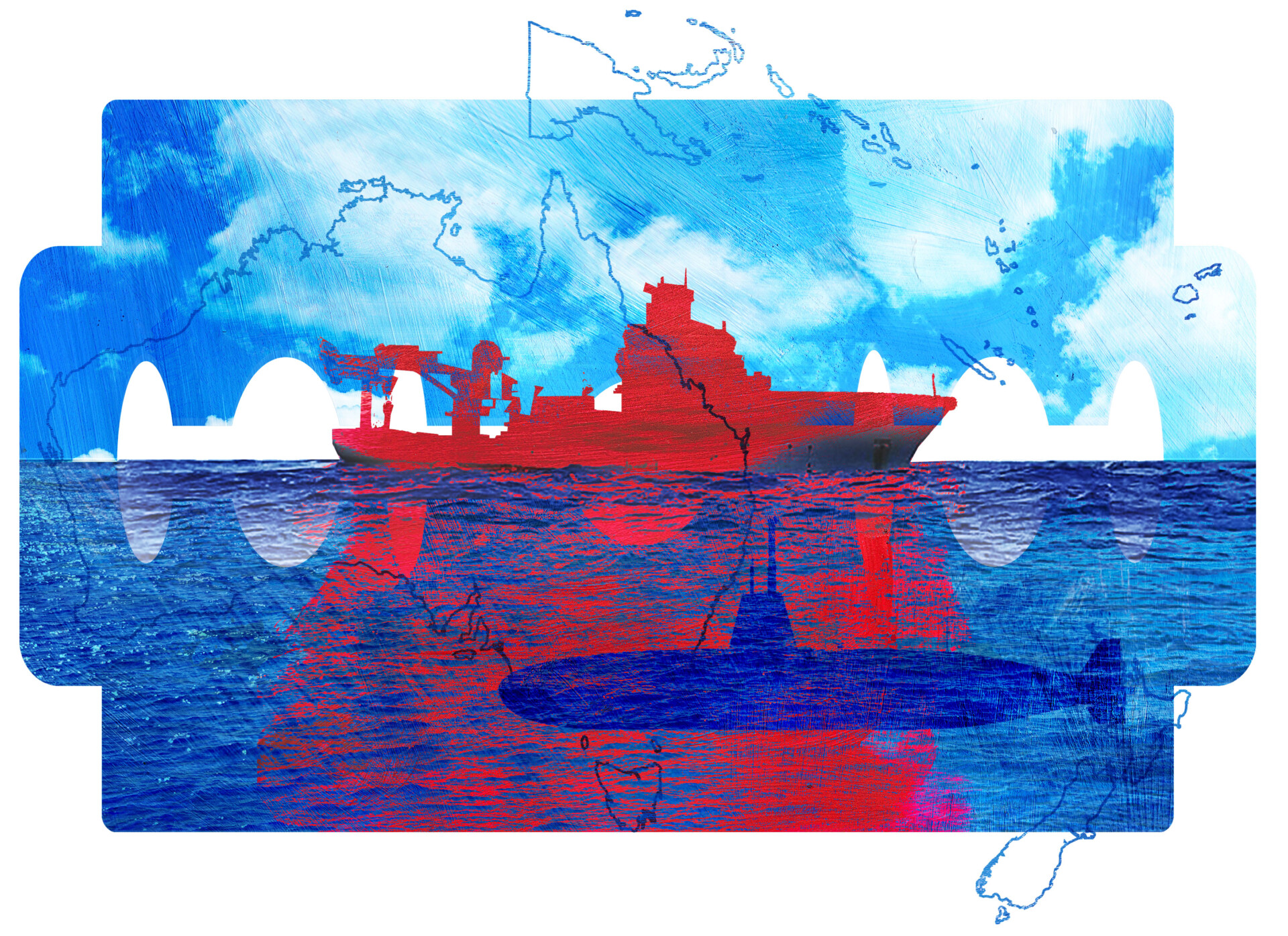

However, Australia’s 2014 decision to refuse or cancel visas on character grounds shifted the source of New Zealand’s illegal narcotics from Asia to Latin America. Since then, increasing quantities of P have traveled the 7,000-or-so nautical miles to New Zealand and Australia from the entrepots of Ecuador, Panama and even Florida, along a so-called “Pacific Drug Highway” that slaloms between the tiny, archipelagic nations of the world’s largest ocean. New Zealanders now pay such a high price for narcotics that cartel leaders know it as “the golden nugget.”

To many outside the region, the Pacific can appear intimidating — even terrifying — in its vastness. But the ancestors of Oceania’s Indigenous people navigated, settled and fished its 60 million square miles in simple outrigger canoes. In these tiny and dispersed places, it is often said that water connects communities rather than separates them. Now, Latin American drug lords are using the same currents and trade winds that islanders have relied on for centuries to connect and expand their colossal, criminal empires.

Rear Adm. Bob Little knows this more than most. From a small office at Camp Smith, Hawaii, he directs the Joint Interagency Task Force West (JIATF-W), which coordinates with Pacific countries to fight drug trafficking and other transnational crime. The Pacific Drug Highway, he said, “has destabilizing impacts on the transit countries,” which lead to “corruption, presence of Mexican cartel activity [and] other destabilizing illegal activity in the region to support that flow.”

Nations like Fiji, Tonga and Samoa barely knew narcotics more potent than marijuana in recent memory. Now they are mired in addiction crises. Mexico’s two biggest organized criminal groups, the Sinaloa Cartel and the Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generacion, are also alleged to have conscripted local political leaders into a trade worth tens of billions of dollars.

Over the past decade, these groups have dispatched increasing quantities of cocaine and meth. Overdoses on the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl have even begun to hit the region. Despite Washington’s “war on drugs” rolling into its 54th year, illicit drug use has never been higher.

On Jan. 31, Fijian military officials confirmed during a press conference in the capital of Suva that Fiji’s police force had requested the Fijian military’s help in combating the country’s drug crisis. Pio Tikoduadua, Fiji’s defense minister, who also served as home affairs minister until December 2024, said that “deploying the military is a serious decision that must only be made as a last resort, and only in situations where civilian mechanisms have been fully utilized and found insufficient.”

Latin American coca production is at record levels, “super cartels” dominate the ports of northern Europe and drugs play a key role in conflicts enveloping places like Afghanistan and Myanmar. If the world’s richest nations can’t contain this estimated $360 billion global black market, how will the small and poor states of Oceania cope?

When Denis O’Reilly, a teenage Catholic seminary dropout, joined Black Power in 1972, New Zealand’s gang scene was “disorganized — as opposed to organized — crime.”

Black Power was, like its rival the Mongrel Mob, composed mainly of young Māori men facing joblessness and racial discrimination. But while the Mob adopted the imagery of Nazi Germany — embracing the “mongrelism” of which it was accused by “pakeha” (white) New Zealanders — Black Power steeped itself in antiracist ideology of the time. O’Reilly, who had a keen interest in Cold War liberation theology, was hooked.

None of this is to say that O’Reilly and his fellow members were ideal civil rights role models. Both gangs attacked the police and each other in running battles, some of which were fatal. But as O’Reilly told New Lines, it was “drunk violence, hooliganism. Just fucking stupid stuff.”

That all changed when P made landfall in 1999. The drug was imported and manufactured in local makeshift labs by the Mob, Black Power or other biker gangs like the Mongols and Hells Angels. Some called it “crank” or “go-fast.” Either way, O’Reilly said, “it was everywhere.”

Not all P was imported from China. But pretty much every constituent, or “precursor,” chemical blended to create it was. Pacific Island nations were used occasionally by Chinese producers to cook meth: In 2004, Fijian cops tore down a Chinese meth factory containing enough precursors to manufacture a billion dollars’ worth of the drug. Most Triad meth was destined for Australia, the “big brother market,” said Bruce Berry, a customs investigations manager, while New Zealand caught small quantities, or “spillage.”

In 2013, the Chinese Communist Party, dismayed at its citizens’ own addiction crisis, cracked down on meth production. On Dec. 29 that year, 3,000 cops raided the tiny, coastal spot of Boshe — which authorities dubbed “China’s Number One Drugs Village”— arresting 182 people and seizing three tons of crystal meth, or “ice.” Boshe’s so-called “godfather” was a CCP apparatchik. He was executed in 2019.

Beijing’s operation pushed meth production across China’s borders to Laos, Vietnam and, most significantly, Myanmar, where drug production had long fueled the country’s civil conflict. Casinos popped up in shadily brokered “free zones” to wash billions of dollars for the world’s richest drug-trafficking organizations. The largest of these was Sam Gor, known as “The Company,” a drug syndicate headed by Chinese-Canadian kingpin Tse Chi Lop and worth several times more than any Latin American cartel.

Nothing changed the Pacific drug industry as much as Australia’s 2014 decision to amend section 501 of its Migration Act, deporting noncitizens who failed a hazily worded character test. Many of the 3,058 New Zealanders deported under the act, known collectively as “501s,” had moved to Australia as boys and had few, if any, support structures in the country of their birth. Some were members of outlaw motorcycle clubs like the Comancheros, a group feared for its violence and connections to the cocaine-trafficking cartels of Latin America.

The 501s took over ethnic gang turf back in New Zealand and executed far larger drug shipments. In 2014, cops busted a 1,100-pound meth shipment in New Zealand’s tropical north. In 2016, a Mexican and a New Zealander conspired to import around $1.5 million of cocaine inside a diamond-encrusted horse head. And the busts kept getting bigger.

The 501s “brought quite a different dynamic and threats to the criminal scene in New Zealand,” Berry told New Lines. The Comancheros had members stationed in Thailand and, crucially, Mexico. They “changed the underworld in New Zealand, and now there’s no going back,” said Jared Savage, a reporter and author of two books on New Zealand gangs. “Everyone is bigger, badder and better than they were before.”

New Zealand, however, deported its own 501s — 1,040 between 2013 and 2018 — to the Pacific Island nations of their birth. They are a “significant contributor” to the expansion of the Pacific Drug Highway, said Jose Sousa-Santos, an associate professor at the University of Canterbury specializing in Pacific security and defense. “Latin American crime groups have, where advantageous, collaborated with local actors to facilitate the movement of drugs as well as servicing local clients. In the Pacific Islands, local criminal networks are used to facilitate the trafficking of drugs through the region by infiltrating law enforcement, customs and other government agencies as well as working with the commercial sector.”

Small and tight-knit Pacific authorities make such corruption far quicker and easier to pull off. In just a few years, the region’s island states have been exposed to levels of narco-state capture that people in Latin America have suffered for decades.

Before Mexico’s cartels became traffickers of Pacific meth, they reached across the vast ocean to get their hands on Chinese precursors to serve the U.S. market. The Sinaloa Cartel’s Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman Loera, for example, wanted a direct precursor pipeline from Asia to Mexico — and his lieutenants forged ties with Hong Kong’s long-established Triads.

But as precursors went in one direction, the Sinaloas also channeled small shipments of their own into Hong Kong, to test the readiness of the Asian market for their most lucrative product: cocaine.

Shipping cocaine that distance made an already expensive drug even more expensive, so the cartel’s clientele was at first limited mostly to the very rich. The cartel worked with the Triads, who had both the underworld and political contacts to find buyers and keep cops off their back.

Cocaine headed west, and meth precursors went east. It was a route Spanish galleons had first sailed in the 16th century, connecting Spain’s colonies in Manila and Acapulco. Now it was a drug trade route — a mutually beneficial arrangement for the Sinaloas and their Triad contacts.

In 2017, when authorities captured El Chapo and extradited him to the U.S., four of his sons, known as “Los Chapitos,” expanded on his efforts in the Pacific and set their eyes on the Australian and New Zealand markets, where — in New Zealand alone — a gram of cocaine costs three times more than in the continental U.S.

The Sinaloas’ rival, the CJNG, soon began sniffing out its own connections across the ocean. And lately, groups in Colombia and Brazil have also sent drugs west. Today, New Zealand’s illicit drug market is worth $2 billion while Australia’s is estimated at $11 billion. Ports at the dispatch end of this highway, particularly in Ecuador’s largest city, Guayaquil, and its Galapagos Islands, have seen a stunning rise in violence in the past couple of years.

But Pacific Island states have been hit hard, too. Bags and containers of cocaine have been found on beaches and hidden in boats across islands thousands of miles apart — from the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia to the Marshall Islands, Tonga, Samoa, Papua New Guinea and Fiji.

French Navy Rear Adm. Geoffrey d’Andigne, who commanded military forces in French Polynesia until August of last year, told New Lines that “the typical method is a sailing boat, taking the route of the world tour people, which usually go from the Galapagos to the Marquesas or French Polynesia, then entering the South Pacific and Oceania. They appear like any other sailing ship and then when they arrive, after 15 days at sea, they usually need to rest, to refuel and to get some food.”

Owning a sailboat is expensive, as is taking it out to sea for weeks or even months at a time. For some pleasure craft sailors, moving drugs is a way to subsidize their lifestyle. Some will continue with their illicit cargo after stopping for supplies while others will pass the drugs to another vessel.

The cartels move drugs across the Pacific Islands hidden in yachts, shipping containers, fishing vessels or planes as they move along a winding map of different routes, frequently changing hands to make them even harder to track. By 2030, container tonnage in the Pacific is expected to increase nearly 250% over 2000 figures.

Even in the European ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp, authorities are only able to search 8% of containers. In New Zealand, that figure is 2%. In some Pacific Island nations, it’s closer to zero. For this reason, busting shipments is almost entirely reliant on human intelligence, which becomes tougher if cartels pay off or threaten workers. According to Berry, cartels can lose 9 out of 10 shipments and still make a profit. And besides, they’re still innovating.

American authorities have grown accustomed to “narco subs,” homemade vessels meant to avoid detection as they embark on underwater trafficking sorties. Yet in November, a Colombian-led law enforcement operation, involving more than 62 countries, tracked one of these subs carrying 5 tons of cocaine 1,250 miles southwest of Clipperton Island, a tiny French-claimed atoll in the Pacific. It was the first narco sub detected in Oceania. Authorities claim that it and five others were carrying drugs bound for Australia and New Zealand.

But Latin American cartels themselves have a limited physical presence along the Pacific Drug Highway and work closely with other criminal groups to move their products. Jim Ink, an American law enforcement professional with decades of experience chasing organized criminals across the globe, who now serves as the senior law enforcement adviser to JIATF West in Hawaii, tells New Lines that when it comes to the Pacific drug trade there are lots of interested parties — not least among islanders.

“In many cases, you have not only the criminal organizations coming out of the Western Hemisphere, largely the Mexican cartels, but also mixing with Asian criminal organizations like the Triads or even Southeast Asian [groups], and then some of the [Pasifika] Indigenous groups and facilitators along there,” Ink said. “There’s opportunity in the Pacific.”

There is also a mounting addiction crisis. Pago Pago is the seaside capital of American Samoa and the only U.S. territory south of the equator. Just about 44,000 people live on the territory’s five islands, scalloped with pristine beaches and covered in thick, green jungle. The water is clear enough to see fish at the bed of Pago Pago’s harbor.

But the beauty of the islands belies the struggle of living in one of the world’s most isolated places. A clue to its latest calamity is writ large on a billboard beside Pago Pago’s main road. It depicts Roman Reigns, a Samoan-heritage WWE wrestling star, with text in Samoan urging youngsters not to take drugs. Cops are finding ever-larger quantities of meth, sometimes alongside firearms. Raids by the islands’ small police force haven’t stemmed the tide of meth — nor its use.

“It’s evident the territory has a drug problem,” the territory’s top cop, Falanaipupu Taase Sagapolotuele, told BenarNews in January 2023, “and over the last six years, the government established a drug task force, but no solutions are coming out from that task force.”

In November 2023, officials in American Samoa signed a bilateral agreement with the nearby Independent State of Samoa, where drugs and guns are also appearing more often, to have their respective law enforcement agencies work together to figure out how drugs are coming in.

Meanwhile, addiction has skyrocketed around the Pacific Islands — and, like New Zealand in the early 2000s, island criminals are now cooking meth locally, with Mexican cartels taking a cut of the profits.

There are “indications that, in particular, what otherwise would be Mexican-produced meth is beginning to be offshored,” Little said, “with Mexican cartels beginning to infiltrate partners in the region where certainly the potential, from a profit margin and/or diversifying risk standpoint, it benefits the cartels to push some of that production outside of their country.”

No island nation has felt the effects of the drug highway more keenly than Fiji. A collection of 332 islands home to around a million people, its reputation as a tourist hotspot and surf paradise has masked decades of civil strife, coups and infighting that have left it open to cartel exploitation on a colossal scale.

In January 2024, police seized almost 5 tons of meth worth $2 billion in two raids near the holiday town of Nadi, its largest-ever bust. Within weeks, a ton had gone missing — allegedly at the hands of corrupt cops. Thirteen men have been charged over the bust. However, analyst Santos-Sousa said that “there have not been substantive arrests beyond the immediate low-level arrests at the time of the seizures. This suggests that the high-level actors within these networks are still protected.”

With so much meth leaking into local communities, Fiji now has a chronic addiction crisis of its own — with almost no harm-reduction policies in place to combat it. “Not only is it killing the youth, it’s killing our children too,” Tikoduadua told New Zealand’s 1 News during an interview in May of last year. “If we do not solve this drug problem in Fiji soon, our nation is going to be a nation of zombies.”

In January, as Fijian officials announced that their military could soon play a role in the government’s fight against drugs, they sought to assuage concerns of a wider assault on personal freedoms in a country with a long history of military coups and crackdowns. Tikoduadua told reporters in Suva there is “nothing to fear.” The military would play a purely supporting role, working to “ensure that their involvement is consistent with the law.”

“We have come a long way in terms of reconciliation and restoration. There has been a lot of inner healing within the military,” Tikoduadua said. “However, we must also acknowledge the deliberate boundaries between civilian governance and the military’s role. The [military’s] readiness does not mean it is the first solution to every challenge the nation faces.”

Santos-Sousa warned against implementing a U.S.-style war on drugs in Oceania. While such a narrative “might be useful to secure more material resources and assistance to combat transnational crime, the danger is that it damages the economies and reputations of Pacific countries reliant on tourism and investment.”

“The drug war mentality didn’t work in the U.S. either,” he added. “Pacific countries could adopt narratives such as ‘the war of our generation’ as emblematic of the challenges faced at all levels of state and society.”

Even New Zealand, which has historically clean public systems and last year ranked third on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, has begun to experience isolated pockets of bribery among port and police officers. “New Zealand corruption is normally in the realm of money: I’m paying someone to do something, to survive or thrive,” Berry said. He fears a transition to something more dangerous. “When you look at the Sinaloa Cartel … they don’t use money. They use intimidation. They use threats.”

Berry adds that this process may accelerate due to the increased presence of “trusted insiders” drafted from the 501s, who are “bringing that tradecraft and accelerating the connectivity to organized crime.”

If there is one group New Zealand’s law enforcers appear to be taking more seriously, it’s the Comancheros. Last August, police arrested 18 men — its entire chapter — in Christchurch, the nation’s second-largest city. But last March, following a report by local nongovernmental organization The Drug Foundation, authorities admitted they were struggling to understand a huge leap in drug use across the nation. Cocaine use has skyrocketed. There have even been cases of overdose deaths from fentanyl, whose production has, like meth, shifted from China to Mexico. The Pacific Drug Highway, it seems, has never functioned more smoothly.

Its riches have also turned the heads of young New Zealanders who may otherwise have joined its ethnic biker gangs. Last August, authorities busted the “Mongrel Mob Kartel,” a gang operating in and around the capital city of Wellington. Shortly afterward, regional members of the Mongrel Mob and Black Power convened on Matiu/Somes Island, a 62-acre outcrop that sits in Wellington’s huge, natural harbor. Members from each gang paired up for a dive course that was more political than recreational: Relying on each other would, elders hoped, cure old enmities and galvanize the gangs against the country’s more powerful and violent interlopers.

Savage suggests that a parlay like this may represent little more than “protection” against the authorities, or a merger to better compete in New Zealand’s revamped and gainful narco underworld.

O’Reilly disagrees. New Lines met him at a gathering of Black Power elders in a Wellington hotel room. “There were probably three generations of Black Power in that meeting,” he said. “They’re talking about employment, health care, housing, sports and achievement for their families. No one was talking about organized crime. No one was talking about war against other groups.”

The New Zealand government had just announced the Gangs Act 2024, which mandates the dispersal of gang members, prohibits members from communicating with each other and, most controversially, bans the insignia of 35 gangs, including Black Power. To O’Reilly, this is political theater, taking aim at easy targets while those far higher up the criminal food chain make hay.

“Cartels are also white-collar businessmen, and people who launder the money and that sort of stuff. That’s why the racist paradigm of the ‘gang’ actually allows a lot of the real organized crime to go under the radar,” he said, explaining how law enforcement’s focus on tattooed street gangs diverts attention from more ambitious and sophisticated criminal networks.

In his view, the real issue is the number of groups that are working at a global scale and causing deeper instability across the Pacific. It’s in these groups’ interest to pit smaller, local groups like the Mob and Black Power against each other, exploiting them as proxies. “There is [a] worldwide organized criminal conspiracy [and] organized crime networks,” he said. “That’s fucking real.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.