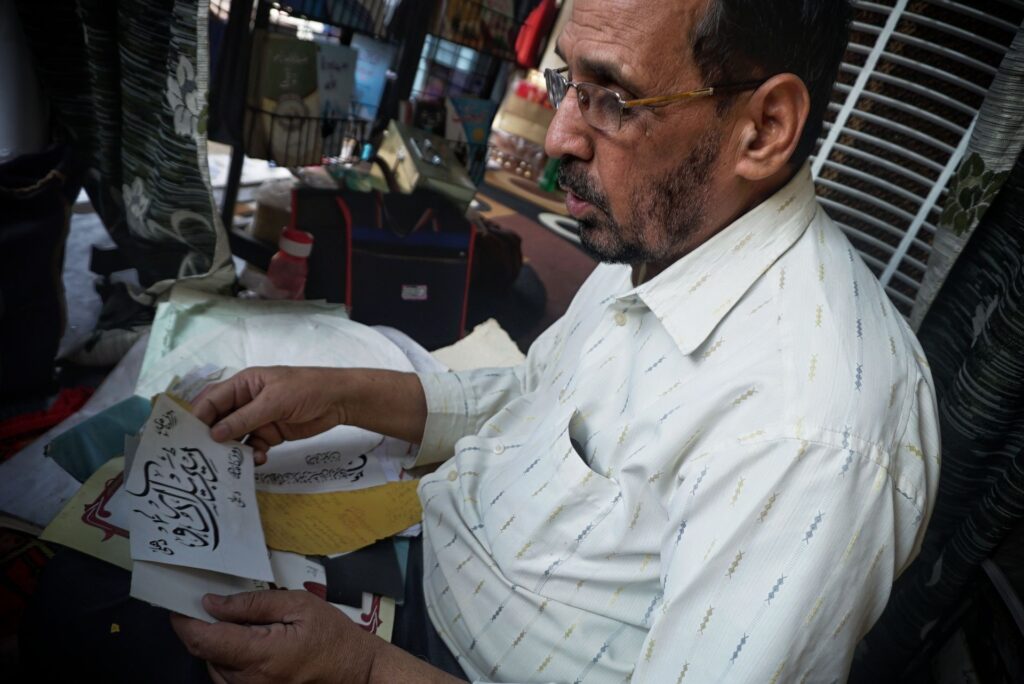

Mohammad Ghalib sits in the corner space of a book shop, barely a couple of square yards large, that was offered to him by a late friend years ago, as he couldn’t afford it on his own. He is the only “katib,” or calligrapher, left in the celebrated Urdu Bazaar of Old Delhi, witnessing his art form dying before his eyes.

On the wall outside the shop hangs a small, barely noticeable, handwritten nameplate in Urdu, Hindu and English, which reads “Katib Mohammad Ghalib,” desperately seeking attention. Amid large flex boards in the busy market, which was once a literary haven for Urdu connoisseurs, the nameplate itself becomes a telling tale of Ghalib’s bygone profession.

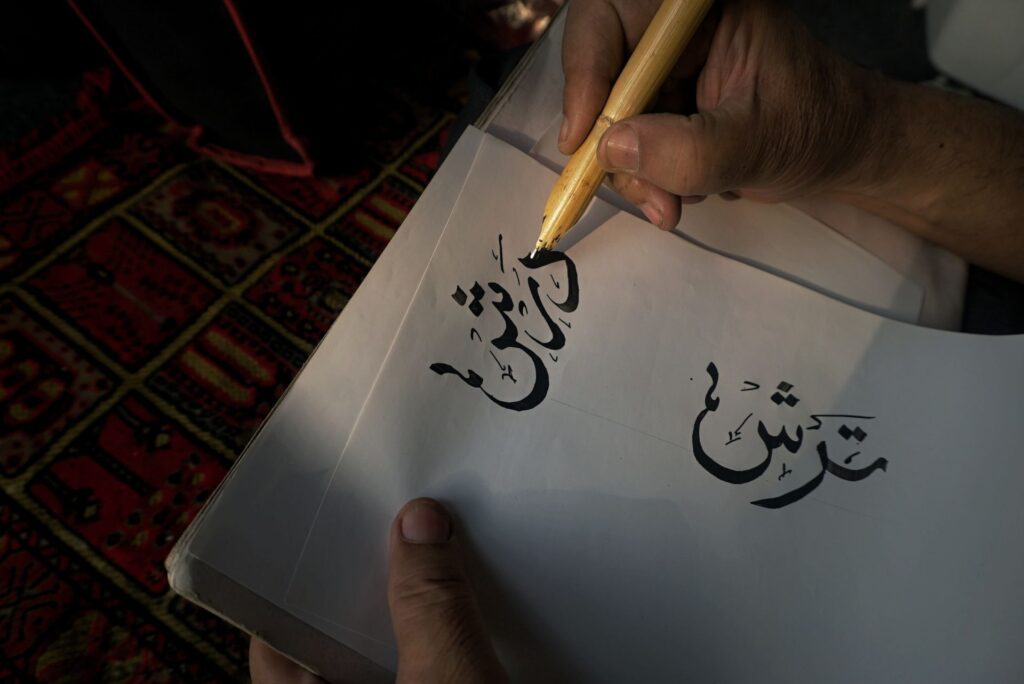

A couple of decades ago, about a dozen calligraphers would make this printing and books market come alive with their sharp bamboo pens, creating an aura of ornamental penmanship with their dexterity and delicate strokes. Holding their breaths tight, they would peck the nib of their bamboo pens in the ink and create unique styles and typographies for invitation cards, posters and logos.

Today, most of them are now dead, while many of the remaining few have retired from the profession, as it became obsolete due to technological advancement and digitization. Ghalib, however, still sets up his small workstation every day and lives in nostalgia.

“Kitabat,” or calligraphy, is a centuries-old art form in the Indian subcontinent, which attained its peak during the Mughal era. It was used to write the “farmaan” (official decrees) of the royal courts, as well as manuscripts, books, journals, newspapers, postcards and lineages.

“In earlier times, katibs were hired for Munshigiri [a position held by officials to maintain accounts] and were placed in royal courts,” says Ghalib. “It was the most respectable job. I am proud of the fact that even kings used to learn the art of kitabat and nawabs [governors in the Mughal era] used to keep at least one katib in their court for writing books, biographies or about their kingdom.” He adds that, “It is known as ‘shahi fun,’ or the royal profession.”

“If any needy person came to the door of a katib and he had nothing to spare, the katib would write a word, any word, and tell the person to take it to Red Fort [the primary residence of Mughal emperors from the 17th century onward]. When he showed it to even a doorman, he would recognize that some katib had sent him and [would] fulfill all his needs,” explains Ghalib. After a breath, with an expression as if giving his final verdict about the buried brilliance, Ghalib adds, “Even Aurangzeb was a katib. And Dara Shikoh. Such was the value of a katib.” (Aurangzeb was the sixth Mughal emperor; Dara Shikoh was his elder brother and heir apparent whom he defeated, eventually arranging his execution for the throne.)

In kitabat, he says, one needs to be very dedicated. “A person gets lost in this work. It demands your full attention. Even a small movement of the hand can cost greatly. You have to hold your breath in order to write precisely. You can’t talk much when you begin writing; distraction is unforgivable.”

The Urdu Bazaar in Old Delhi, where most katibs were stationed, also dates to the Mughal era. The very word Urdu, which means “camp” in Turkish, refers to the army camps in the area. Facing the eastern gate of the Jama Masjid, a large field that lay adjacent to the grand mosque was called Urdu Maidan, or army’s field. The two markets on each side of the grand mosque’s gate were known as Urdu Bazaar. “The army would fetch their essentials from these markets. The supplies of army disposals, including jackets and boots, would be available in this market till [the] late 1970s,” Sohail Hashmi, a Delhi-based writer and historian, tells New Lines.

Toward the end of the Mughal empire, books and printing shops emerged in this market, where one could find the best Urdu books, including translations of the Quran, the Vedas and Ramayana. Poets, writers, readers and publishers would throng the bazaar to discuss the latest Urdu literature while sitting on benches outside the bookstores. Inside their shops, there would be a dedicated corner for the katibs.

The rise of kitabat in the bazaar can also be traced to the lifetime of the famous court poet of Urdu and Persian, Mirza Ghalib, whose mansion in the neighborhood has been designated a heritage site by the Archaeological Survey of India. “Mirza Ghalib would come to this market to get his new work proofread, calligraphed by katibs and compiled as a diwan [collection],” Hashmi says.

The bazaar, along with the city of Delhi, first took a hit during the Rebellion of 1857 — the first major uprising against the British. Mirza Ghalib was heavily dismayed and lamented its destruction: “Urdu bazar ko koyi nahi janta tha to kahan thi Urdu / Bakhuda! Dehli na to shahar tha, na chavni, na qila, na bazaar.” (“When no one knew Urdu Bazaar, then where was Urdu? By God! Delhi was no longer a city, nor cantonment, fort or bazaar.”) The second major blow came during the Partition in 1947, when several Urdu poets and writers migrated to the new state of Pakistan. Over time, the market that had once bustled with book shops, printing presses and katibs became home to eateries serving Mughlai delicacies.

Almost two centuries after the 1857 rebellion, Mohammad Ghalib shares a similar pain. At 60, he is also ailing from many diseases: diabetes, heart disease and hypocalcemia.

He studied kitabat, introductory Arabic and Persian, and qirat (recitation) at Darul Uloom Deoband, the renowned seminary in India, from 1979 to 1983. His calligraphy teacher Munshi Imtiyaz was the son of Munshi Ishtiyaq, one of the most prominent katibs and teachers of Arabic in India in the 20th century. Later, Ghalib migrated to Delhi from the north Indian city of Saharanpur to work as a calligrapher. He has been in the Urdu Bazaar for four decades.

Since then, Ghalib has calligraphed academic books for the National Council of Education Research and Training, a government organization that prepares school curricula. He has also written by hand three volumes of “Tareekh E Arabi Adab” (History of Arabic Literature), authored by Dr. Abdul Haleem Nadvi, known for his contributions to Arabic studies in India. Ghalib has also worked for the National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language. Nowadays, however, he frequently returns home without any work for days and sometimes weeks. “Now all work is done by computers and I am mostly jobless,” he laments.

Once upon a time, calligraphers like Ghalib would be among the busiest professionals in the market, working day in and day out completing their assignments. “There used to be so much work. We would work even on holidays. We would receive assignments to write books on multiple genres, including academic books,” Ghalib says. Professional katibs with expertise in the craft are known as Har Fan Maula, which translates to “jack of all trades,” a tag given to calligraphers who are experts in writing many languages and scripts.

The craft is traditionally practiced with a “qalam,” a pen made from dry bamboo, which is used to write several scripts of Urdu and Arabic calligraphy including Thuluth, Nastaleeq, Kufic, Naksh and Diwani. “Contemporary calligraphy has taken the shape of an aesthetic art with colors and other decorative elements. They write Arabic in different ways, in colorful ways,” he explains. “People now write with brushes while we practice with wood pens. If you ask them to do some fine work or write a newspaper, they won’t be able to do it.”

For Ghalib, kitabat means everything. Despite the challenges, he speaks of it with a high sense of honor, in euphoria. “It is dearer to me, more than my own life,” he says. “I have earned a lot of things because of this profession. Because of this profession, I met a number of educated people.”

He traces the decline of kitabat to almost two decades ago. “I witnessed the sharp decline when most of the books were typed on computers 15 to 20 years ago,” he says. He acknowledges that technology gets work done quickly. It would take a month for Ghalib to write a book of about 500 pages, which typists could complete within a week.

“I will tell you one thing,” Ghalib continues. “I, too, would have left it [calligraphy] a long time ago. I am not boasting. I am Har Fan Maula — I write in Urdu, Persian, Hindi, Arabic and English. Sometimes, they would call me to the courts to write their papers. Last time, a few people from Medina, Saudi Arabia, sent 15 property papers in Arabic through someone. I do every kind of work. I write posters, receipts, etc.,” Ghalib says. His recent assignments have been limited to receipt writing for Islamic seminaries in Kashmir during Ramadan, designing calligraphic logos and layouts for wedding cards.

The only institution that still uses this dying craft in India is The Musalman, an Urdu newspaper published, or rather handwritten, in the city of Chennai, capital of Tamil Nadu, a state in south India, 1,400 miles from Ghalib’s workspace. Published since 1927, The Musalman is a daily, four-page paper, currently run by Syed Arifullah, the youngest son of its former editor, Syed Fazlullah.

The craft has also taken a hit due to language politics in South Asia. Prior to India’s Partition, Hindustani, a vernacular of the country’s northern regions, especially Delhi and its surrounding area, bifurcated into Hindi and Urdu. After Partition, Pakistan adopted Urdu as its official language, which further complicated the language politics, yet a 2011 census showed that India still had over 50 million Urdu speakers. Over time, however, the language has come to be taught only in madrassas, which is why Muslims in India have come to be seen as its sole proprietors. Even young Muslims in India don’t engage with the language as much anymore. “People actually don’t read Urdu now … writing in Urdu is a little costly,” Ghalib says.“They print in Urdu, only if someone insists. Otherwise, they say who knows Urdu now?”

Ghalib too has fallen victim to this unfounded language divide of late. “Here [India], even if I upload a video on Facebook, they call me Pakistani. The condition here is such that you can’t even write anything in favor of uplifting the Urdu language. Hindus in India think that Urdu is the language of Muslims. Many people call me ‘Pakistani Khatat’ on my Facebook,” Ghalib laments. (Khatat is another word for katib.)

Four decades later, Ghalib is now dealing with his poor eyesight. His hands shiver while holding the pen. He takes long gasps before making each stroke on the paper. He is too withered to do any intricate work requiring precision. His teeth have fallen out due to disease and medicine. “I can’t eat properly, can’t even hold a cup of tea easily. My work suffers,” he says in a tone of exasperation.

Even on the days when Ghalib returns home without any work, he still holds out hope that “enthusiastic people” will eventually visit his little corner. “Sometimes, when I don’t have work for a week, I do not let this art die at home,” he says. “I return to my shop and then it is like Allah sends work one day that compensates all those days.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.