Desperate screams of “Moto! Moto! [Fire! Fire!]!” disrupted the usually peaceful “adhan,” or the Muslim call to prayer, which rolls through the air from the Riyadha Mosque, first built nearly a century ago, and into residents’ homes in Nairobi’s Pumwani — established in 1922 as the city’s first African estate, or planned living area.

The screams came from Pumwani’s Gikomba market, located adjacent to Riyadha Mosque and one of the largest open-air markets in Africa, where traders sell mostly secondhand clothes and shoes. These fires rip through this lively market at least a few times a month. Pumwani’s residents increasingly suspect that unscrupulous private developers are behind them.

When the loud commotion finally reached 29-year-old Zulfa Wambui, her heart immediately sank. One afternoon several months ago, she left her 3-year-old son to play with other neighborhood children outside her makeshift home beside the market’s busy throughway, while she went about her work selling food nearby.

“I ran as fast as I could,” Wambui tells New Lines. She speaks softly and her lips quiver. “When I got to my home, the fire had already reached there. I was screaming and crying. I couldn’t find my son anywhere.”

Wambui, a mother of four other children aged between 10 months and 16 years, frantically sifted through the charred debris of what was once her home, throwing scorched dishes and household items to the side. “I was going through the remains of all my belongings that were burned,” Wambui says, taking a seat on a crate at the site of her former home, now reduced to an ashpit.

“Then I pulled a piece of clothing from the rubble,” she continues, as shouts from petty traders haggling over prices at the market punctuate her speech. “And then with the clothes came chunks of what looked like a brain. I knew immediately that this was my son.”

Pain abruptly overwhelms Wambui, and she breaks down into hysterical cries, her body shaking. She tries to continue her story, but all that comes out are sniffles and futile attempts at holding back tears.

In this once predominantly Muslim community, with its original inhabitants first settling here a century ago during the colonial era, many residents believe these fires are only the most visible component of larger government attempts to systematically cleanse Pumwani of its local Muslim population and erase the city’s distinct Muslim history with them.

With Muslims now comprising a minority of Pumwani’s population — and scores facing imminent evictions from their own community — it is not difficult to understand why this theory is so widespread.

“Pumwani is always burning,” Wambui says, after she regains her composure. “I think it’s the rich people who are coming here and starting these fires.” Her eyes scan the scorched earth around her, her lips trembling. “They don’t want us here.”

No one knows what or who is behind these frequent fires that have intermittently ripped through people’s homes in Pumwani over the last two decades, leaving devastation in their wake. But locals believe they are likely arson attacks carried out at the behest of private developers who are eying the lands around Pumwani.

With its close proximity to the city’s central business district — about two miles away — Pumwani’s lands are ever-increasing in value. According to a trustee at the Pumwani Riyadha Mosque, which owns land along one of the main streets cutting through the estate, a half-acre of land here is worth at least 1 billion Kenyan shillings (about $7.4 million).

Now, more private and government developments planned in the area are only driving up the value of this land — and pushing poor residents out. The city’s development goals have been outlined in the Nairobi Metro 2030 initiative, which aims to transform the capital into a “world class African metropolis by 2030” and “an iconic and globally attractive city,” instilling fear into the city’s mostly poor residents whose violent evictions often coincide with these lavish new imaginings of one of East Africa’s largest cities.

Behind the advertisements and billboards decorating Nairobi’s streets and highways, which display pictures of tall and glistening high-rise apartments and office spaces, a war over land is being waged. In a city with a long history of private actors and government officials colluding and overseeing illegal land grabs, disputes over land can often turn brutal — and Pumwani has become a flashpoint.

“There’s a huge amount of land pressure in the city and a realization by entities — both private and public — that some of these neighborhoods where the housing is poor can be part of this highly profitable process of urban renewal,” says George Kegoro, a lawyer and former director of the Kenya Human Rights Commission. “And this then leads to extremely violent evictions.”

The government has already constructed a six-floor, ultra-modern market building at Gikomba as part of its project to transform the neighborhood’s open-air market into a state-of-the-art shopping center. Authorities have claimed that this development is intended to put an end to the ceaseless fires that wreak havoc on the market.

Pumwani’s residents, however, say that as interest in the land around the market increases, so do the fires.

Fires are a common occurrence throughout Nairobi’s informal makeshift settlements, sometimes owing to residents not being connected to the city’s electricity grid and having no choice but to tap into it illegally — at times causing power lines to burst and melt.

According to Kegoro, however, private developers are also often behind fires that erupt in poor neighborhoods around Nairobi — an attempt to avoid the prolonged legal process of evicting residents who have lived in these areas for decades. Oftentimes, they hire impoverished and vulnerable youths in the community to spark them, residents say. Most of these fires occur at odd hours — either when the majority of residents are away or when they are at home, asleep.

Despite Nairobi’s ambitious urban development goals, Pumwani continues to resemble an informal slum in every aspect besides the estate’s communal water infrastructure — which residents genially describe as being “built by Queen Elizabeth’s father” — and pockets of affordable apartment units that mirror American public housing, with their flat exterior walls checkered by small windows.

Before Kenya’s independence in 1963, this was a tightknit and well-organized community. “Life was very different back then,” recounts 86-year-old Maalim Hassan. He is one of the oldest original residents of Pumwani, and Nairobi’s history continues to dance behind his large, tired eyes. He leans back on a couch at his apartment and takes a deep sigh.

“Pumwani was the center of business for all African life in the city. All the famous Kenyans who fought for independence stayed in this estate,” he says. “It was never a slum like many journalists these days like to say. It was organized and had all the necessary facilities — streets, lights, everything.”

The first Africans to build homes in Nairobi were Muslims, who hailed from urban societies along the coast, where the British had first disembarked when they arrived in present-day Kenya in the late 19th century.

These societies are broadly known as “Swahili” and mainly comprise Bantu, Afro-Arab and Comorian ethnic groups inhabiting the East African — or Swahili — coast, which encompasses the Zanzibar archipelago and stretches to the shores of mainland Tanzania (formerly known as Tanganyika), Kenya, northern Mozambique, the Comoros Islands, southwestern Somalia and northwestern Madagascar.

According to Yusuf Nzibo, a local historian and author of “The Swahili and Islamization in Nairobi, 1888-1945,” Muslims came to the interior and founded Nairobi’s first African settlements at the turn of the 20th century. These villages were in part connected to the caravan and slave trade. The British military had also become dependent on Swahili porters and African soldiers from the King’s African Rifles (KAR), a multi-battalion British colonial regiment created in 1902, for the conquest of the territory. These soldiers made Nairobi their home following military service.

The British decision to establish a railroad camp, supply depot and railway station for the Kenya-Uganda Railway in Nairobi in 1899, which became the railway’s headquarters, attracted scores of people to Nairobi who sought new opportunities.

By 1910, all but one of the city’s eight African settlements that were registered by the colonial government — and which together consisted of about 10,000 residents — were developed and built by Muslim ex-service members, according to Anders Ese, an urbanist and co-author of “The City Makers of Nairobi: An African Urban History.”

They came from across the Swahili coast — cities in present-day Kenya such as Malindi, Mombasa and Lamu, along with the Comoros Islands, Zanzibar and the coast of what was then Tanganyika. Nubians, originating from the central Nile Valley in present-day northern Sudan and southern Egypt, and Somali ex-service members also created settlements.

According to Nzibo, the primary Swahili settlements that developed in Nairobi at this time included Pangani, which was first settled by migrants from the Pangani region of then Tanganyika, though Muslim converts from the Kamba and Kikuyu ethnic groups eventually became the majority there. Another was the “Mji wa Mombasa” settlement, Swahili for “city of Mombasa,” whose residents originated from across the Kenyan coast.

Colonial authorities often referred to these early Muslim settlers as “detribalized natives” — Africans who had lost connections to their “original” societies and had no place to return to after military service. According to researchers, throughout the colonial period, authorities discussed what to do with these urban Muslim residents in the city.

These early settlements “continued to fill up with men from the British service,” Ese says. “Having converted to Islam while serving in the KAR, many gravitated towards Muslim communities in Nairobi. These burgeoning communities attracted others already in service; people hailing from East Africa and beyond. They all converted to Islam.”

“Muslim identity and Islam became cornerstones for all the African settlements,” Ese says. “Newcomers adopted Muslim ways of living and donned coastal attire. They changed their diet and did what they believed necessary to emulate the outer workings of being a Muslim.”

In a social process that would similarly define the future Pumwani identity over decades, conversion to Islam coincided with the converts severing their ethnic and rural ties; they found a new home and identity in these early Nairobi settlements.

In the 1920s and ’30s, following World War I, the British began enacting stricter racial segregation policies in the city, borrowing designs from apartheid South Africa and expanding their direct control over Nairobi’s African residents. Other than those whose employers were obligated to house them, African residents who had gained employment in the city were compelled to live in an “official location” — an area reserved for African housing.

Colonial authorities decided that these African residents should be housed in the eastern side of Nairobi’s town center, far from the European suburbs but close to the emerging industrial zone that depended on African labor, Nzibo says. The construction of this location, which initially spanned 130 acres, began at the start of 1922 and would be called “Pumwani” — meaning a “resting place” or a “place to breathe” in Swahili.

Pumwani became Nairobi’s first “site and service scheme,” Ese explains, meaning the site was laid out in a grid system with basic infrastructure in place — water, roads, waterborne sewage sanitation and simple drainage. The colonial government and municipality were responsible for amenities and services.

Later in 1922, Mji wa Mombasa, which also included the displaced populations of two smaller Swahili settlements that were razed in 1919 to make room for Asian-only cemeteries, was demolished. Its residents were offered 324 plots in the new Pumwani estate.

These new residents were expected to build their houses themselves, and were only permitted to use mud and wattle as construction materials. They built traditional Swahili homes, square-shaped and made from mud — the most common form of housing found along the Swahili coast at that time.

According to Ese, these homeowners paid a monthly rent for the plot on which the house stood. Despite owning the houses, there was no land tenure security for the occupants. During the colonial era, these plots could not be sold, but families could inherit the property.

This first settlement of old Pumwani, which still has Swahili-style mud houses lining its pothole-riddled streets, is referred to as “majengo,” meaning “houses” in Swahili. But the estate would be extended several more times over the decades. By 1931, the population of Pumwani was already 7,173, about 3,000 more than its envisaged capacity, according to Nzibo.

Pangani, which is located around 2 miles from Pumwani, was demolished incrementally between 1931 and 1939, after prolonged protests stalled the eviction process. Its demolition was only greenlighted when the construction of a new extension to Pumwani was completed. Known as “Shauri Moyo,” it comprised 175 cement houses for 3,042 people — less than the population of Pangani at the time.

Pangani’s landlords vehemently opposed the move to Shauri Moyo since they would be regarded as “head tenants” instead of homeowners — and their families would be denied any rights to inheritance. The deal was so unpopular among Pangani’s residents that the name of the estate in Swahili means “consult the heart,” referring to the heart-wrenching process of deciding whether to accept the offer or move elsewhere.

Muslim settlers who were relocated to Pumwani would soon establish the foundations of a burgeoning urban African identity, tightly entrenched in Islam and Swahili culture. Authorities would refer to these Muslim pioneers in colonial-era documents as the “Native Muhammadin,” insinuating that, for these “detribalized natives,” Pumwani was now their home.

Hassan was born in Pangani in 1937. His family eventually accepted a house in Shauri Moyo during the yearslong demolitions in Pangani. Each formative moment of Kenya’s colonial history and its African residents’ agitations for freedom took place on these same streets where he grew up. He was already 15 years old when, in the 1950s, the Mau Mau anti-colonial uprising transformed Pumwani’s usually peaceful streets into a temporary war zone.

Yet before this prolonged anti-colonial revolt culminated in Kenya’s independence — setting in motion Pumwani’s slow degradation over the decades — the estate existed for half a century as a unique and predominantly Muslim community, where various African ethnicities, cultures and languages united under a distinct urban identity.

“In Pumwani we lived like brothers and sisters,” Hassan remembers. “We never practiced discrimination over religion and no one ever enforced their beliefs on others. We were merely a Muslim community that tried our best to accommodate other people.”

Throughout Kenya’s colonial history, people from various ethnicities migrated to Pumwani from their rural villages, escaping the suffocation of life on “native reserves” or the harsh realities of “squatting” on European settler farms that had gobbled up huge swaths of Indigenous lands.

They came to find better economic opportunities, while women often traveled to the city in protest against rural cultures forcing them into positions of servitude. Leaving behind traditional cultures that generally did not allow women to own or inherit property, 41% of houses in Pumwani were women-owned by 1932, according to Nzibo.

As these diverse newcomers arrived, with most only understanding their own Indigenous languages, they relied on the kindness, patience and guidance of the already established Pumwani residents to help them carve out a new home for themselves in an unfamiliar city.

Newcomers and the original Pumwani residents alike were constantly searching for ways to forge familial bonds, Hassan says. This would sometimes include taking an “oath,” in which residents would drag a sharp knife across their fingertips; each person would then rub their wounds together to symbolize their unification through this exchange of blood. Hassan personally witnessed his father take such an oath with three Kikuyu women who had recently arrived in Pumwani.

“And it was something real,” Hassan says, knitting his eyebrows together, accentuating the seriousness of his words. “Once you did that oath, you truly became like a family. You became siblings. It was something very serious. People were coming from many different places for many different reasons and they needed to create new connections. They created new families while living in the city.”

Newcomers also embraced Islam en masse. This, Hassan says, stemmed from the example the original Pumwani residents set for the newcomers. “The Muslim homeowners rented out rooms and employed the non-Muslims coming into Pumwani,” Hassan explains. “The non-Muslims were always treated as family … and that’s how people started to naturally convert to Islam … because of the strong moral character displayed by Muslims.”

Today in Pumwani, residents say that even the estate’s longtime Christian residents “behave like Muslims” — including fasting with their Muslim neighbors during the holy month of Ramadan.

In the same process that occurred among the so-called detribalized natives who became the first African settlers in Nairobi, once these Pumwani newcomers converted to Islam, their connections to their rural villages were severed, as their religious conversions breached their community’s traditional norms. As a result, many were rejected by their families in the villages.

Separated from their rural homes, they learned Swahili and adopted traditional Swahili attire and culture. Importantly, a new identity was simultaneously emerging — one that defied ethnic divisions, and united around religion and language. This identity was firmly rooting itself deep into Pumwani’s urban landscape.

“Pumwani was a place of astonishment,” Hassan remembers. “We had people and cultures from everywhere — from Rhodesia [now Zimbabwe], Tanganyika and the Comoros Islands. There was so much music and dancing. Everyone was part of Pumwani.”

Pumwani’s streets were often overrun by dynamic and colorful expressions of various cultures, with different groups showing off their music, poetry and dance; these performances are known as “ngoma” in Swahili. According to Nzibo, it was the Beni ngoma form, which was developed along the coast from the early 1900s, that was most widely practiced among Africans in Nairobi.

In the early years of Pumwani there were five Beni groups, some of whom developed rivalries that would be publicly expressed through performances and processions. Cultural and social clubs materialized and festivals, parties and parades were organized.

Pumwani Memorial Hall was constructed by the British in 1925 and served as a dedication to the KAR soldiers who lost their lives in World War I. As Pumwani’s population increased, two additional wings to the hall were added in the early 1940s. Various activities were organized here, including dances, tea parties and sewing groups.

In 1932, an African football stadium was constructed — called the “Native Stadium,” later renamed the “African stadium.” Today it is known as City Stadium. According to Ese, it became an important arena for the governor to address African crowds, while football instilled a “sense of national pride and an early ‘Kenyan’ identity.”

There were aspects of life that Hassan frowned upon, such as people drinking in the Pumwani Brewery, a government brewery and beer garden — the sales from which the British would use to finance amenities in the estate — and another bar in Shauri Moyo. Yet Pumwani’s residents always behaved with respect, he says.

“People would drink only inside the bars. They would never dare to drink openly on the streets,” Hassan explains. “Back then, people had a lot of respect for the elders.”

This image diverges sharply from the current state of Pumwani, in which a street near the Riyadha Mosque, nicknamed the “red light district,” is crowded with people stumbling over their own feet as they openly chug down illicit alcohol, like “busaa,” a cereal-based fermented beer, and “changaa,” a traditional home-brewed spirit.

Despite British authorities commonly describing Pumwani in colonial documents as “overcrowded,” “dilapidated” and “filthy,” Hassan tells New Lines with conviction and pride that this was not the case. “Pumwani was never overcrowded; we all used to know one another. And it was clean. It wasn’t anything like it is now,” he says. “These stereotypes of Pumwani were just lies.”

Ese has also debunked many of these colonial descriptions and caricatures of Pumwani in his research. Pumwani was “a vibrant and creative society … where wealth could coexist with poverty,” Ese explains.

In his book, Ese includes an aerial shot of Pumwani from 1970 that shows the orderly, grid layout of the location. It is likely to have been the same in prior decades.

Besides the square-shaped mud houses expressing old coastal architecture, now infilled with makeshift homes constructed from tin sheets, and the Pumwani Memorial Hall still standing almost a century later, the state of today’s Pumwani feels vastly different from Hassan’s old neighborhood. It was the years after Kenya’s independence that pushed this once unique urban community into its grave.

It is nearly impossible to find anyone in Pumwani who has not received an eviction order, whether verbal or written. Year by year, as the Muslim population shrinks, its future appears more distorted and unclear.

“This community is dead,” says 65-year-old Mustafa Saleh in a raspy voice, emitting a somberness that echoes in the voices of all of Pumwani’s long-established residents. “It’s only a name that’s remaining. The land is already grabbed. We are just waiting for the day we get evicted.”

“This is my only home,” Saleh adds. “There’s nowhere else for me to go.” Unlike most of Nairobi’s current inhabitants, who continue to have strong ties to their rural homes, for many of Pumwani’s longtime residents, these now-overburdened and neglected streets are where their souls were planted and remain firmly rooted.

“Only God knows where I will end up,” Saleh continues, with a shrug. “When I am evicted, I will say, ‘Alhamdulillah’ [praise be to God]. In the end, these evictions are just a reminder that this world will never be our home. Paradise is our only true home.”

Since the country’s independence, there has been an explosion of people migrating to Nairobi from rural villages in search of work. Pumwani’s close proximity to the central business district, along with economic opportunities at the Gikomba market, have made it a convenient location for scores of people hailing from the rural regions.

With Christians making up about 80% of Kenya’s population, by the 1980s this mass influx of rural migrants to the capital completely overturned Pumwani’s Muslim-majority demographic — greatly diluting these urban identities. Along with the government’s eventual neglect of the estate’s long-established residents, this has taken a toll on Pumwani and its residents’ sense of belonging.

“It was after independence when everything started to change,” Hassan says. “All of our local [city] counselors and representatives were not from Pumwani. They were all Kikuyu from outside the community.” The Kikuyu, who originate from central Kenya and make up about 22% of the country’s population, have long dictated the country’s political and economic life since independence.

The political administration of Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, who served as leader until his death in 1978, was dominated by his fellow Kikuyu. A new class of African elites, mostly from the Kikuyu ethnic group, emerged in the years following independence. Using their ties to the Kikuyu-dominated government, they were able to acquire massive tracts of land throughout the country.

According to Ahmad Washee, a community elder who is considered a local expert on land issues in Pumwani, by 1974, “the councilors of Nairobi, members of parliament, the mayor, deputy mayor, and the town clerk — all of them were Kikuyu Christians.”

To this day, there have only been a couple of people elected to the larger Kamukunji Constituency, of which Pumwani is a part, who have any ties to the estate’s long-standing local population. And there has never been a member of Parliament from the original Pumwani community.

However, during the early years of independence, some politicians in the new government did make genuine efforts to develop Pumwani. Thomas Mboya, an African trade unionist and nationalist who had spent time in the United States and was honored by Martin Luther King Jr. in 1959, was appointed MP in the Kamukunji Constituency in the 1960s.

According to the Pumwani-Majengo Tenants Association, Mboya forged an agreement with Pumwani’s residents for an estate upgrading scheme that was meant to eventually provide permanent housing to all residents in Pumwani at that time, both landlords and tenants.

He completed the first phase of the project, which resulted in the building of the high-rises California and Biafra to house landlords and tenants, respectively. But Mboya, an outspoken critic of government corruption, was assassinated in 1969.

During the autocratic rule of Daniel arap Moi, who served as president from 1978 to 2002, the upgrading scheme continued with the establishment of Highrise Phase I. This phase was also done sincerely by the government. After 20 years of paying low, standardized rents as per their lease-to-own agreements, these tenants now own their apartments.

However, the continuation of this program has been marred by allegations of corruption and government negligence. In the late 1990s, the government shifted to issuing land allotment letters — a precursor to the provision of a title deed — to Pumwani’s remaining landlords, sparking resentment among the estate’s tenants who remain propertyless.

“All of us here in Pumwani could have been settled in decent housing if the government had followed Mboya’s plan,” says 48-year-old Issa Muhammad Abdi, a local tenant and former assistant treasurer at the Riyadha Mosque. “It was a project that was meant to continue and benefit all of us in Pumwani. But instead [the government] has divided us into landlords and tenants. Now, all of us who are not landlords are living in fear of being evicted from our own community.”

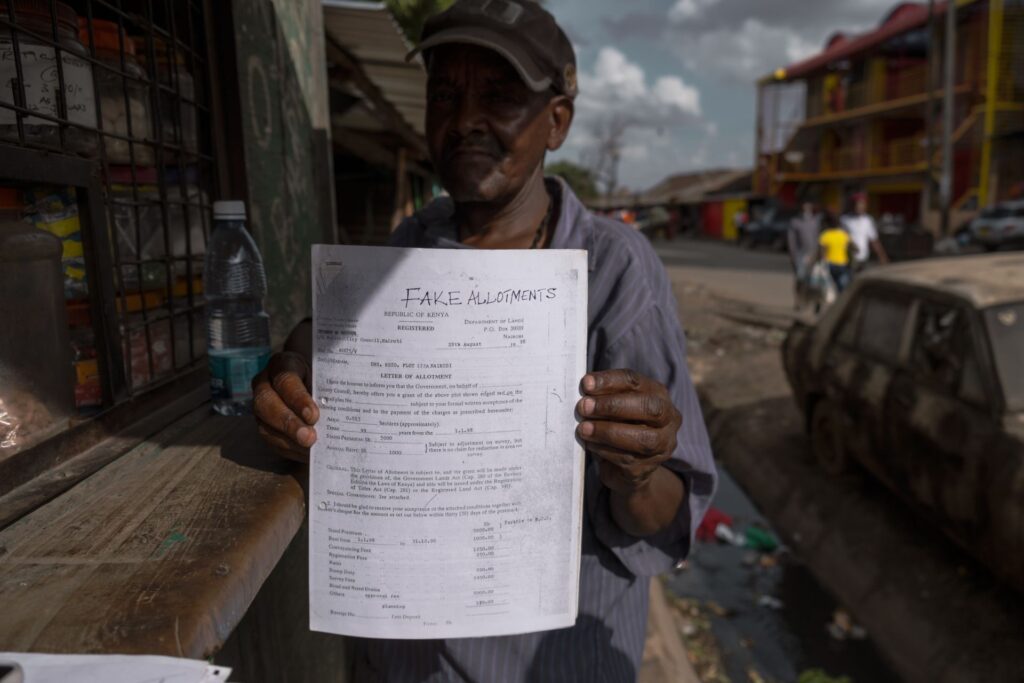

However, behind the scenes, further action was resulting in the mass confiscation of land in Pumwani and its transfer to mostly Kikuyu Christian owners. It was the allocation of these allotment letters in the late 1990s that would bring this to light.

According to Washee, starting in the 1970s, the government began identifying plots in the estate where the owners had stopped paying their land rates. “The [government officials] would follow up with these plots where the owners had died or there were no inheritors. Any unclaimed plots in Pumwani were irregularly transferred [by the government] to Kikuyu owners.”

The culture of old Pumwani, whose residents more or less followed the moral and behavioral code prescribed by Islam, in which Hassan says “people trusted each other and were not greedy,” made them an easy population to target. “No one in Pumwani used to care about land,” Hassan adds. “We didn’t need to.”

Washee shows New Lines a list of these allotment letters, totaling 256 plots. Nearly half of these plots are listed as being owned by Christians, the overwhelming majority of whom are from the Kikuyu ethnic group. This is despite the fact that none of Pumwani’s landlords possessed ownership titles that would have allowed them to sell their plots until the 1990s.

There are also 11 plots that served as community spaces for Pumwani’s residents — such as playgrounds or public restrooms — that were similarly grabbed by developers from outside Pumwani during the allocation process, according to Washee.

These land alienation patterns extant in Pumwani since independence have been repeated throughout Muslim coastal communities in Kenya — from Lamu to Mombasa.

Along with historical and continuing discrimination against Muslims in Kenya’s formal system — from unequal education access to difficulties acquiring national IDs for those with Arabic names, with the government often accusing them of being “foreigners” — this has left the majority of Muslims in Kenya impoverished and landless, according to Kenyan researchers. While this is also the case for other minority groups in Kenya, regions dominated by Muslims record a high percentage of the population in poverty and illiteracy.

Several private high-rise apartments now ascend far into Pumwani’s blue skies, towering above the Riyadha Mosque’s minarets, which were built to be among the tallest points of the estate. Where residents used to look to the sky and be reminded to pray, they are now reminded of their own imminent displacement.

The exteriors of these apartments are decorated with names like “Elite” and “Platinum.” With monthly rents as high as 25,000 Kenyan shillings (about $200) per month, only Kenyans from outside Pumwani can afford to occupy them — and most of them are Christians.

“Some of us here are already struggling to afford 4,000 Kenyan shillings [$32] a month for our rent — so clearly these developments are not for us,” laments 70-year-old Abubakar Ali, who was forced to use his connections in the local government to officially adopt the Kikuyu name “Kamau” — the only way he and his children could get access to national IDs, he says.

Residents are also increasingly fearful of the influence of private developers from neighboring Eastleigh, a predominantly Somali neighborhood and a business hub, though these investments in Pumwani have so far been minimal, according to Washee.

Pumwani’s slow erasure has not just been the fault of corrupt government officials and outsiders. Over the past two decades, since allocation letters were issued, the descendants of Pumwani’s original residents — the “native Muhammadin” — have also been selling their family’s plots to private developers. According to Washee, about 20 plots have so far been sold by families of the original Pumwani landowners.

While residents who oppose these sales often spew harsh allegations at those selling their plots — accusing them of greed, corruption or being unsuspecting victims of government proxies — in reality it seems that poverty has often been the main driver.

The first private development sprung up in Pumwani around 2010 — an apartment and commercial building called “Landmark 2.” The landowners sold their plot to Evans Kidero, the former governor of Nairobi from 2013 until 2017. Kidero was arrested on charges of money laundering and bribery in 2018 and has been investigated for embezzling public funds. This caused rumors to fly among residents that Kidero has used his ties to the government to acquire land in Pumwani through various proxies.

But according to residents who knew the landowners who sold their plot to Kidero before he became governor, the family simply needed the funds to afford treatment for one of their adult children suffering from Parkinson’s disease. Despite the value of land in Pumwani constantly increasing, many residents are no longer able to see any clear future in their community that could convince them not to sell.

“Let’s say you have four people living in a mud house on their plot and renting out rooms where they get about 10,000 Kenyan shillings ($74) per month,” Washee explains. “Then someone approaches you and says I’ll give you 30 million Kenyan shillings ($222,000). With that money, you can buy land somewhere else and still have money left over to start businesses. These are people who are struggling to even afford paying their land rates.”

Hassan has been consumed by pain as he watches more and more residents selling their families’ plots — and the community that raised him is changing irreversibly. “It has made me very sad,” he says, diverting his eyes to the ground. “It makes me feel very bad. But there’s nothing I can do. I also can’t blame them. I understand the circumstances they are living in. I just wish things could be different.”

However, Hassan says that even in Pumwani’s dilapidated state, their forebears would “never” have thought about selling their land — no matter how much money was offered to them. “This new generation just worships money and the duniya [physical world],” he tells New Lines. “They value money over everything else.”

“And it’s not just affecting Muslims,” he adds. “It’s everywhere and it’s affecting everyone. The history of Pumwani and local histories all over the world are being erased — just so people can get their hands on some money.”

But not all of Pumwani’s residents are against the changes. Muhammad Famau, 56, says his family migrated to Nairobi from Lamu about 120 years ago. They eventually made Pangani their home before relocating to Pumwani.

Famau is happy to invite me into his home and offers spiced tea and pilau, a traditional rice dish infused with various aromatic spices — common throughout the Swahili coast. He proudly boasts of his rich Swahili heritage and culture and is keen to show me an old wooden bed frame, carved in a traditional Swahili style, which has been in his family for generations.

Famau, who was issued an allotment letter for his plot, has no plans to sell. “I’m very happy about this private development,” he says. “We need change. It will be very nice to wake up and have a brand-new picture before my eyes. It will make my children’s lives better and their futures brighter.”

“The way Pumwani is now, it is not good for us,” he adds. “We’re tired of living in a slum.”

Just a short walk away from Famau’s home, a fire overtakes a pocket of makeshift homes in Starehe, an area neighboring Pumwani that, along with Shauri Moyo, is slated for demolition for the government to make room for new affordable housing units.

A crowd quickly gathers on the street adjacent to the fire, as onlookers convey their various theories of what — or who — caused it. “It was the government that was behind this fire!” shouts 25-year-old Bushra Swaleh, hurriedly pushing through the crowd.

Swaleh’s eyes are wide and frantic as she processes the reality that her home, along with all her possessions, has just been reduced to ashes. “They don’t want to deal with an eviction process, so they decided to burn us out,” she says, out of breath and with tears running down her face. New Lines was not able to verify these claims, but they reveal the residents’ deep distrust of the government, which is only getting worse by the year.

While some of Pumwani’s residents express hope that they will benefit from these planned affordable developments, most have given up on the idea that the government has any intentions of assisting them. Residents tell me they believe these forthcoming affordable housing units will benefit others and likely serve to exacerbate the evictions of Pumwani’s long-established Muslim community.

They do not need to look far to confirm these fears. Highrise Phase II, the latest phase of the decadeslong upgrading program in Pumwani that was first started in the 1960s, has already turned these eviction worries into reality.

Rashid Saidi, 54, received an apartment unit in Highrise Phase II, the construction of which was completed in 2005. He says that the project, which he initially thought would bring him much-needed peace and stability in his life, has instead dragged him into a prolonged nightmare.

This phase of the upgrading scheme was meant to restructure a long-standing informal village of mud and tin shack houses in Pumwani, colloquially known as “Bash” — the name of which is derived from “The Bash Street Kids,” an old British comic strip. Despite thousands making this settlement their home over the years, only 160 families, who lived there since 1987, when the government conducted a population census, were allocated apartments in the new affordable units. Many of these recipients were local Pumwani Muslims.

According to residents, before the Bash settlement was demolished, the state-owned National Housing Corporation (NHC) increased the agreed-upon monthly rent of 3,400 Kenyan shillings ($25) to 13,000 ($95), not including utilities — an unaffordable rate for most of the recipients. In response, residents protested by refusing to leave their mud and shack homes for about a year. However, early one morning in 2005, the government sent bulldozers to the settlement, pummeling over their homes and forcing the families into the new units.

Residents were then slapped with rent arrears of up to 190,000 Kenyan shillings ($1,400) after the NHC claimed they were responsible for bills that accrued during the year they refused to move into the apartments, Saidi says. Now, many are drowning in debt, with about 70% of the recipients, many of whom are Muslims, facing evictions.

Saidi’s family was forced to move back into their old mud house, which was spared during the demolitions, and rent out their affordable housing unit because they were unable to afford the payments. Even their mud house has been targeted with several demolition orders over the years.

“These so-called affordable housing projects are just another way of evicting poor people from Pumwani,” says Saidi, agitated and smoking a cigarette under the corrugated tin sheet that serves as a roof on his mud house. “So many people facing eviction from these units are Muslims. And this has contributed to the belief that the government is targeting us and trying to erase us from the city.”

Yassin Awadh Mahfudh, 42, is still visibly shaken after his mud home, near the Gikomba market, burned down a few months prior. His three children, aged 8 to 13, have still not been able to return to their schools, as all their school uniforms and books were burned in the fire, along with the rest of the family’s belongings.

“All of this makes me feel very mad because this is my home,” Mahfudh says, with his 8-year-old son standing closely beside him. “I don’t know what’s causing all of these fires, but I can’t finish a week without seeing at least one.”

“If it is these rich people like everyone says, then that is evil,” he continues. “That mud house was all I had. It’s not right what is happening here. This government doesn’t care about us. In Nairobi, the rich are always getting richer, and for the poor the only direction we can go is down.”

Pumwani is forever changed and, despite growing feelings of hopelessness among its long-established residents, the unity and kinship of the old community can still be seen.

Residents from across the social spectrum — community activists, mosque-goers, teachers, elders, sex workers and even thieves — kindly welcomed me to Pumwani and generously shared food, drinks or “khat” — a plant used as a stimulant in the Middle East and Africa.

One resident nicknamed “Mganga,” Swahili for a traditional medicine man, runs a small cafe from a mud house. He offers visitors meals of beans and chapati, an unleavened flatbread common in East Africa, “on the house” — revealing the continued culture of hospitality that had decades ago made thousands of Africans from all over the country feel at home in this once strange city.

Yet these are likely the last years in which Pumwani’s unique urban culture will ever be witnessed.

As its residents are evicted one by one, the estate’s history and its distinct Muslim character are being swept into the landfills to make room for more opulent high-rise apartments and shopping malls.

“If the government continues like this, then the entire history of Pumwani — and with it the history of Kenya — is going to be erased,” says Abdi, the former assistant treasurer at the Riyadha Mosque.

“This place should be preserved as a historical site,” he continues. “But now the people of Pumwani are getting lost and scattered — and Nairobi’s entire African history is becoming lost with them.”

Hassan tiredly shakes his head and begins wiping the palms of his hands together, as if brushing off what is left of the estate that formed his entire identity. “Pumwani is already finished,” he says. “We have no choice but to just accept this now.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.